Francis Picabia

Paysanne (Peasant Woman)

Paysanne

(Peasant Woman)

c. 1940-1942 Oil on board 46.5 x 37.2 cm / 18 1/4 x 14 5/8 in 55.4 x 46 cm / 21 3/4 x 18 1/8 in (framed)

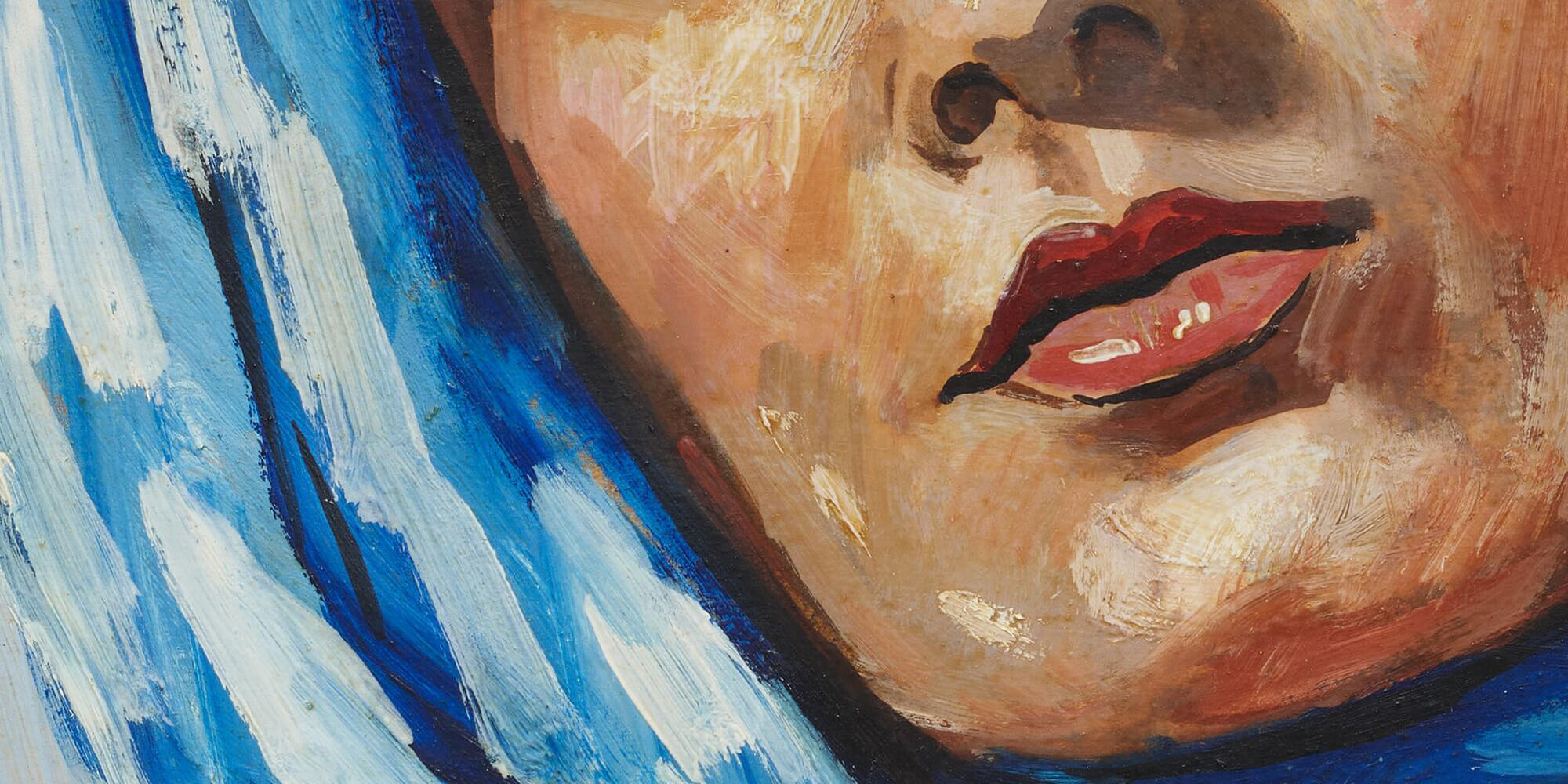

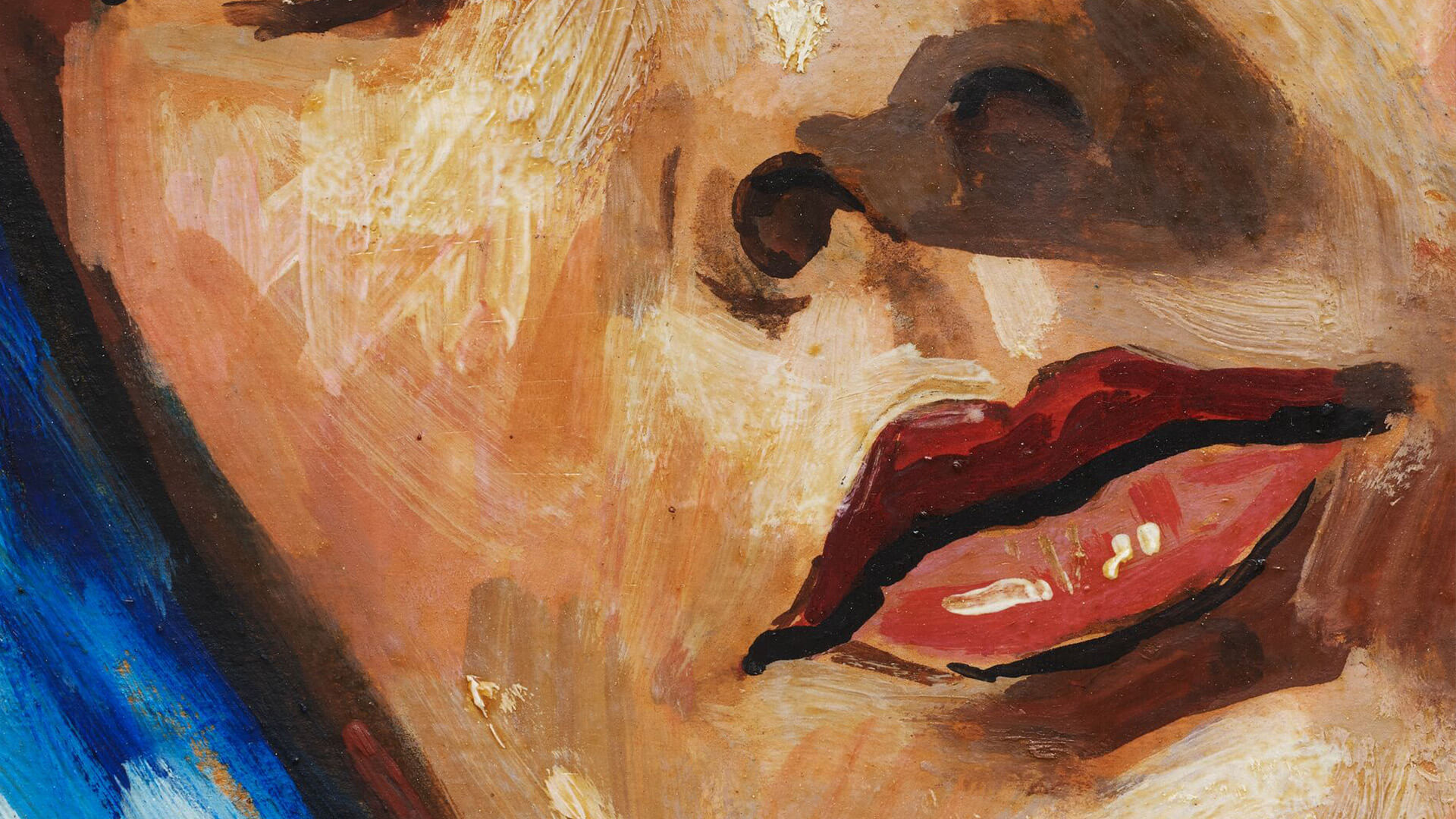

Beguilingly graceful, ‘Paysanne’ (c. 1940-1942) combines elements from a number of Francis Picabia’s most fascinating series of female portraits. Celebrated for his radical appropriation of different techniques and styles, Picabia also appropriated a wide variety of sources for his innovative compositions. These included canonical imagery taken from ancient frescoes, Byzantine icons and Renaissance masterpieces, as well as Hollywood headshots, and photographs he found in magazines, such as ‘Paris Magazine’, ‘Paris Sex Appeal’ and ‘Mon Paris’. ‘Paysanne’ draws on each of these.

‘Picabia, being very prolific, belongs to the type of artist who possesses the perfect tool: an indefatigable imagination.’—Marcel Duchamp, 1949 [1]

‘Paysanne’ exemplifies Picabia’s ingenious plurality of sources and inspirations. The painting is based on an image by Swiss photographer Martin Imboden published in the January 1935 issue of ‘Paris Magazine’ yet differs from the original in significant ways. The vibrant blue scarf which frames the classically beautiful face evokes iconic depictions of the Virgin Mary in ‘Marian blue’. Picabia created a number of paintings of the Madonna, including the Pompidou’s ‘Maternité’ (c. 1935-1936), for which the artist adapted a composition by Correggio. Blurring the sacred and the profane, ‘Paysanne’ recalls both Christian iconography and the characteristics of glossy commercial photography.

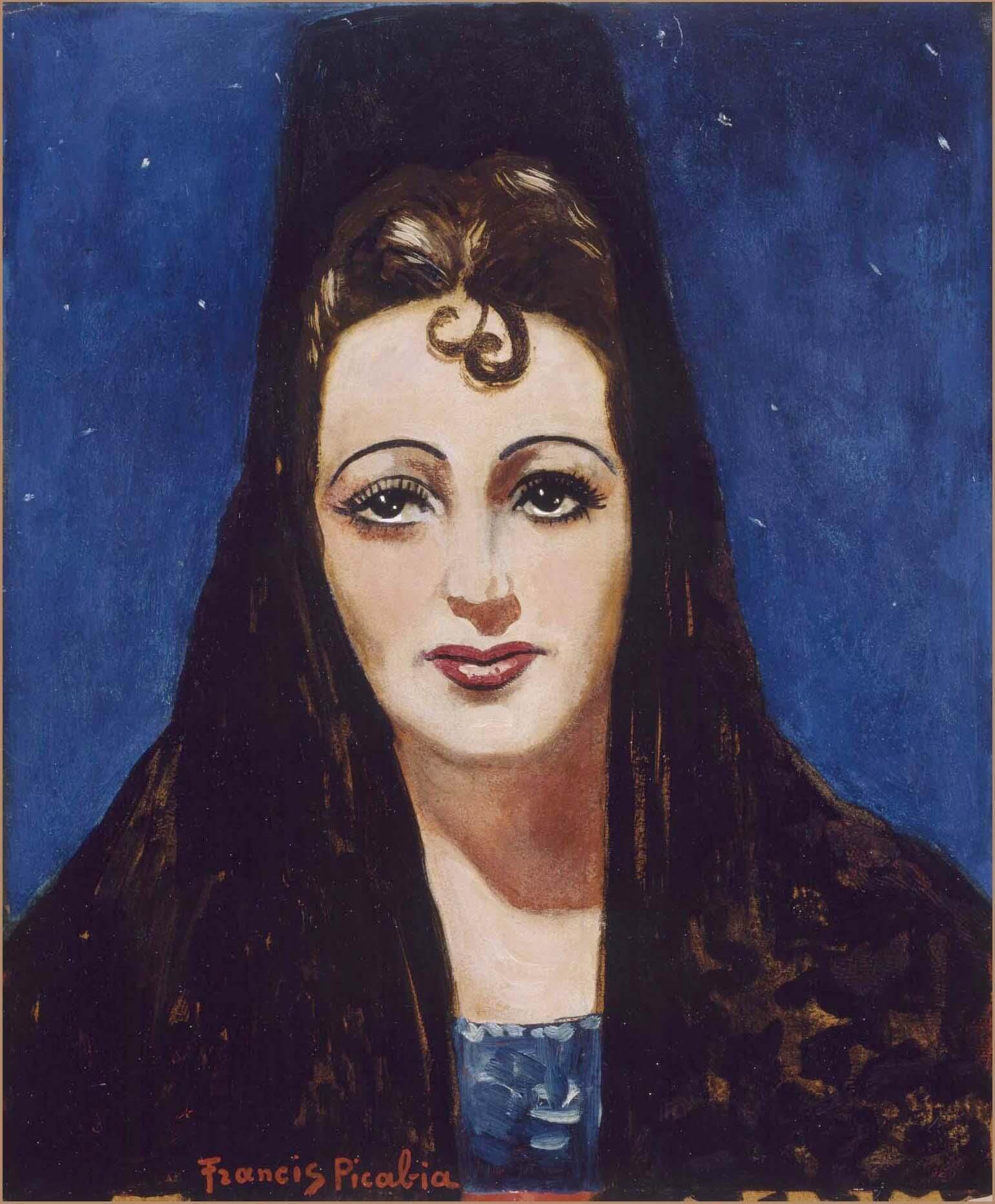

Throughout his career, Picabia used a range of head coverings as a framing device, including in his series of women wearing traditional mantillas, such as the Reina Sofía’s ‘Imperio Argentina’ (1940-1941). Often painted in a strong color, they highlight the expressive facial features he portrayed. In his female portraits from the 1940s, this trope accentuated Picabia’s complex juxtaposition of painting and photography, cleverly emphasizing both the presence of the camera and the hand of the artist. While its artificial lighting and cropped snapshot angle have photographic origins, ‘Paysanne’ is nevertheless conspicuously painterly with vigorous brushstrokes and tactile layers of paint.

Picabia’s richly diverse and confounding oeuvre is marked by fluid movement between figurative representation and abstraction, and experimentation with a variety of reoccurring motifs, including female headshot portraits. During the 1940s alone, Picabia created a series of realist nudes, several works in which the artist superimposed images akin to his earlier ‘Transparencies’, as well as bold abstractions alongside more traditional landscapes inspired by postcards and his surroundings on the Côte d’Azur. Shortly after their completion, Picabia sent an important group of these works, including ‘Paysanne’, to André Romanet’s Galerie Pasteur in Algiers.

Francis Picabia, Imperio Argentina, 1940-1941 Collection Museo Reina Sofía

Describing the paintings Picabia made during the early 1940s in the South of France as ‘Intimate Banalities’, Roberto Ohrt discusses their significance within the history of art: ‘the writers of art history gladly left aside Picabia’s uncomplicated use of realistic motifs, for this simple adjustment meant that the remainder of his work was much easier to fit into the doctrines of avant-gardism. … These therefore seemed shocking whenever they did occasionally come to light and threatened to undermine the entire structure of Modernism or at least that of the avant-garde figure Picabia’. [2]

‘Paysanne’ embodies Picabia’s profound disruption of conceptions of painting and Modernism. His appropriation and combination of ostensibly contradictory motifs and source images from the canon of art history and ‘low’ popular culture continues to have a profound impact on generations of new artists. Like much of Picabia’s most influential work, ‘Paysanne’ is at once traditional and modern, elegant and kitsch, sardonic and thoughtful. It exemplifies why during the 1940s Marcel Duchamp famously described Picabia’s career as a ‘kaleidoscopic series of art experiences’. [3]

Hauser & Wirth Rämistrasse

Located in Zurich’s historic central cultural district, on the same street as our Publishers’ Headquarters, the Rämistrasse gallery is surrounded by renowned establishments which have hosted an international community of artists and intellectuals for more than a century. Francis Picabia’s ‘Paysanne (Peasant Woman)’ can be viewed by appointment alongside works by 20th-century masters and contemporary artists represented by the gallery.

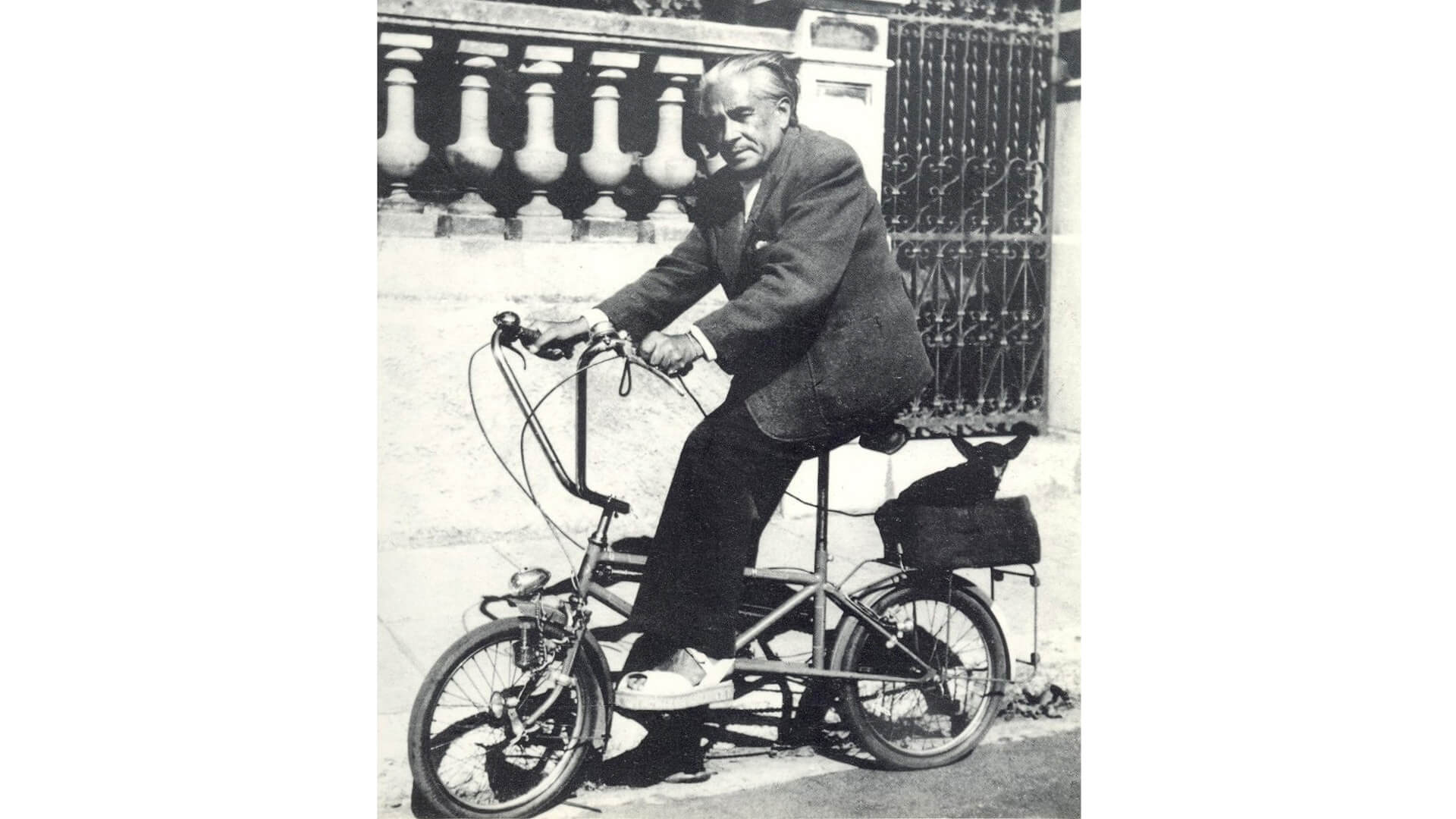

Images: Francis Picabia, Paysanne (Peasant Woman), c. 1940-1942 © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2021. Photo: Thomas Barratt; Martin Imboden, Muriel, Zürich, c. 1932. Sammlung Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur; Francis Picabia, Imperio Argentina, 1940-1941 © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2021. Collection Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid; Francis Picabia on his bicycle with his dog Ninie in September 1940 © Archives Comité Picabia. Photo: Olga Mohler Picabia; Hauser & Wirth Rämistrasse, Zurich, 2020. Photo: Jon Etter.

[1] Marcel Duchamp in Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson (eds.), ‘The Essential Writings of Marcel Duchamp’, London/UK: Thames and Hudson, 1975, p. 156. [2] Roberto Ohrt in Felix Zdenek (ed.), ‘Francis Picabia. The Late Works 1933-1953’, New York NY: D.A.P., 1998, p. 10. [3] Marcel Duchamp in Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson (eds.), ‘The Essential Writings of Marcel Duchamp’, London/UK: Thames and Hudson, 1975, p. 156.