David Smith

Sprays

‘I belong with painters, in a sense; and all my early friends were painters because we all studied together. And I never conceived of myself as anything other than a painter because my work came right through the raised surface and color and objects applied to the surface.’

—David Smith, 1960

VR Walkthrough

This HWVR exhibition features the late post-war American artist David Smith, including six virtual museum loans alongside significant works spanning from 1958 until 1964. ‘David Smith. Sprays’ is a journey throughout this pioneering body of work, curated by the artist’s daughters and co-presidents of the David Smith Estate, Candida and Rebecca Smith, and Dr. Jennifer Field, Executive Director of the David Smith Estate.

Candida Smith on the Sprays

Daughter of the artist and co-president of The Estate of David Smith, Candida Smith remembers, ‘The way he would grab things and use it in a spray drawing was very improvisational, and to a child’s eyes, improvisation is the same thing as play… The Sprays were part of our lives just like the rest of my father's artwork. It was intermingled with everything that we did all day and what he did in the night after we were asleep.’

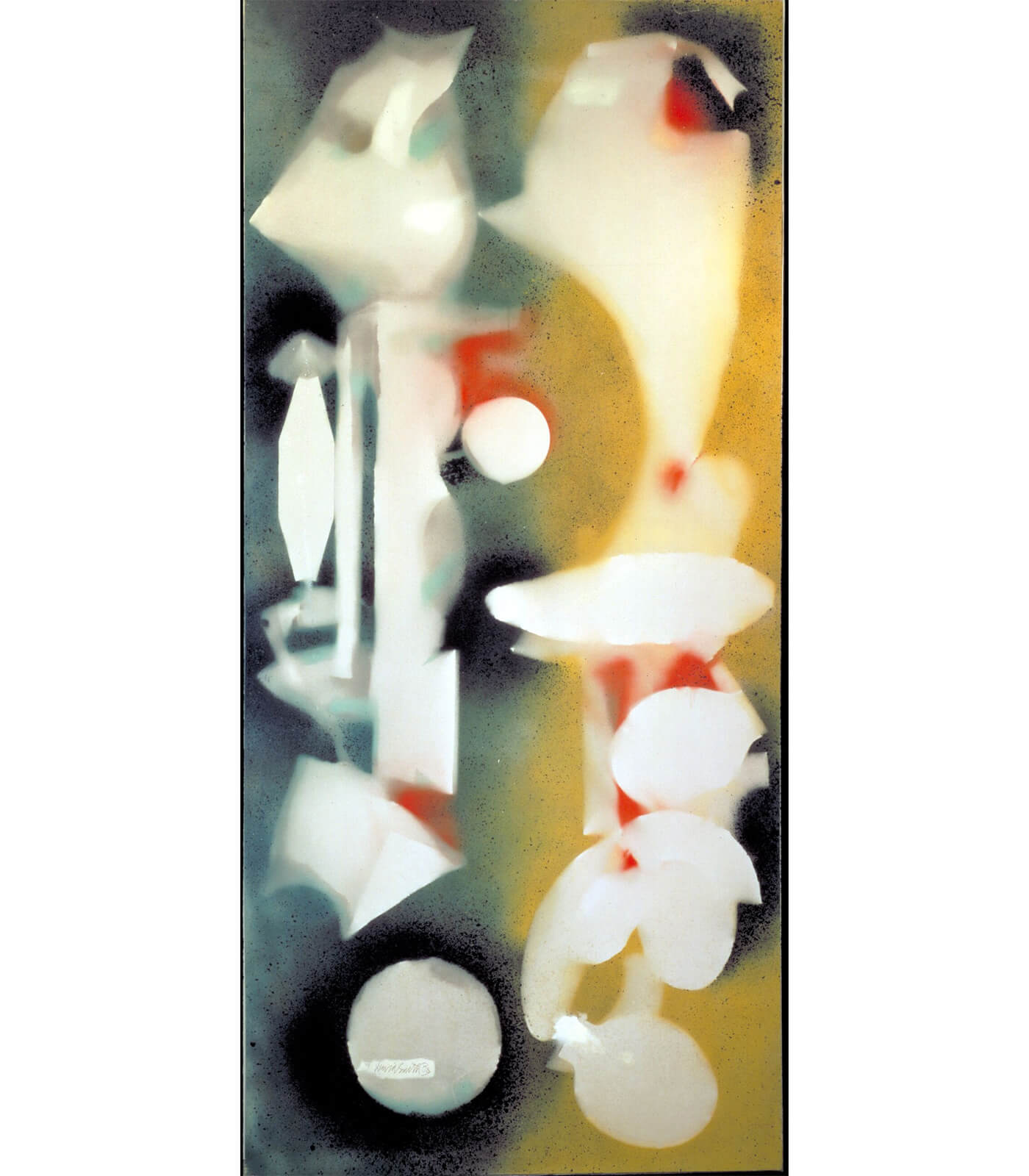

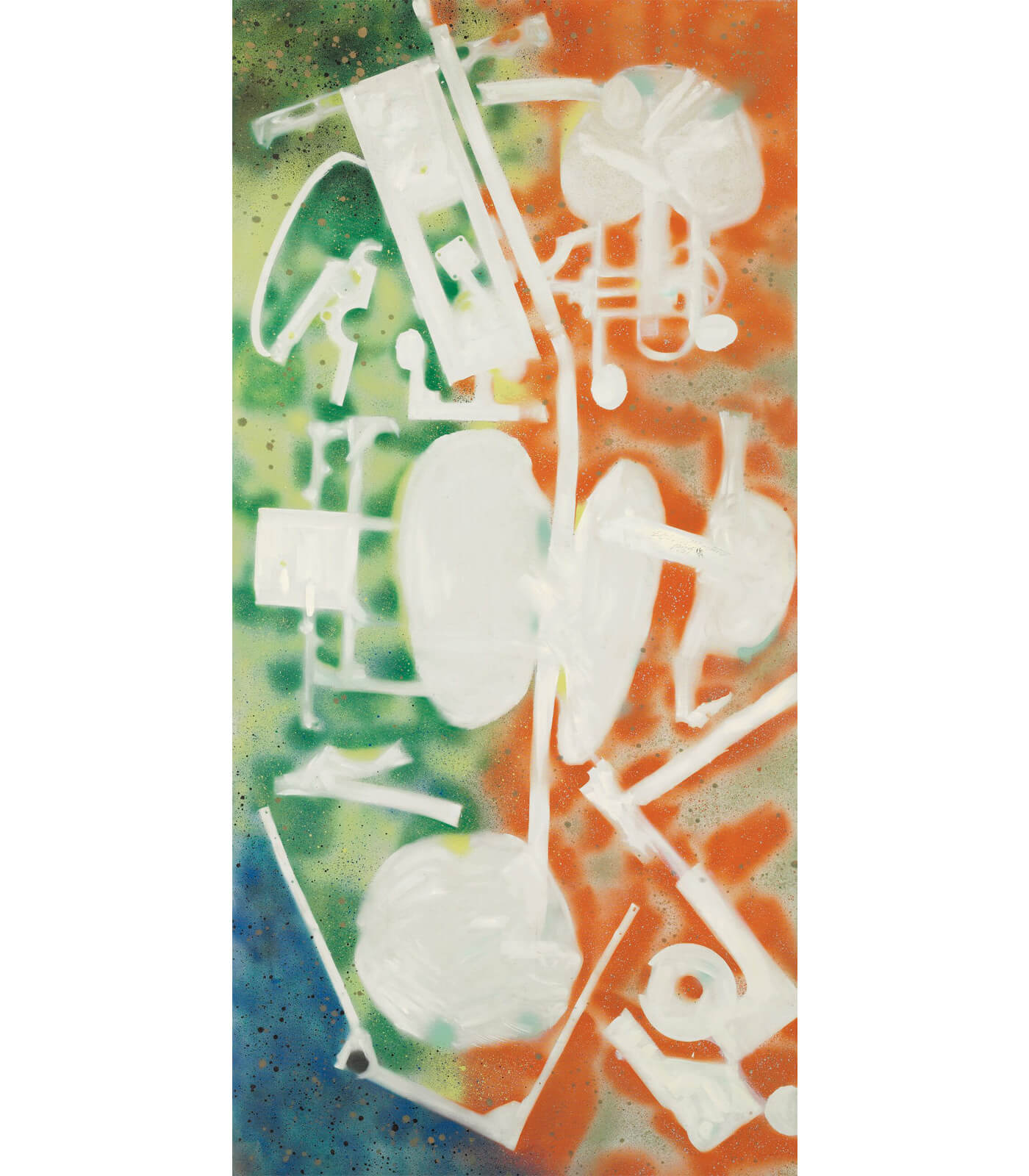

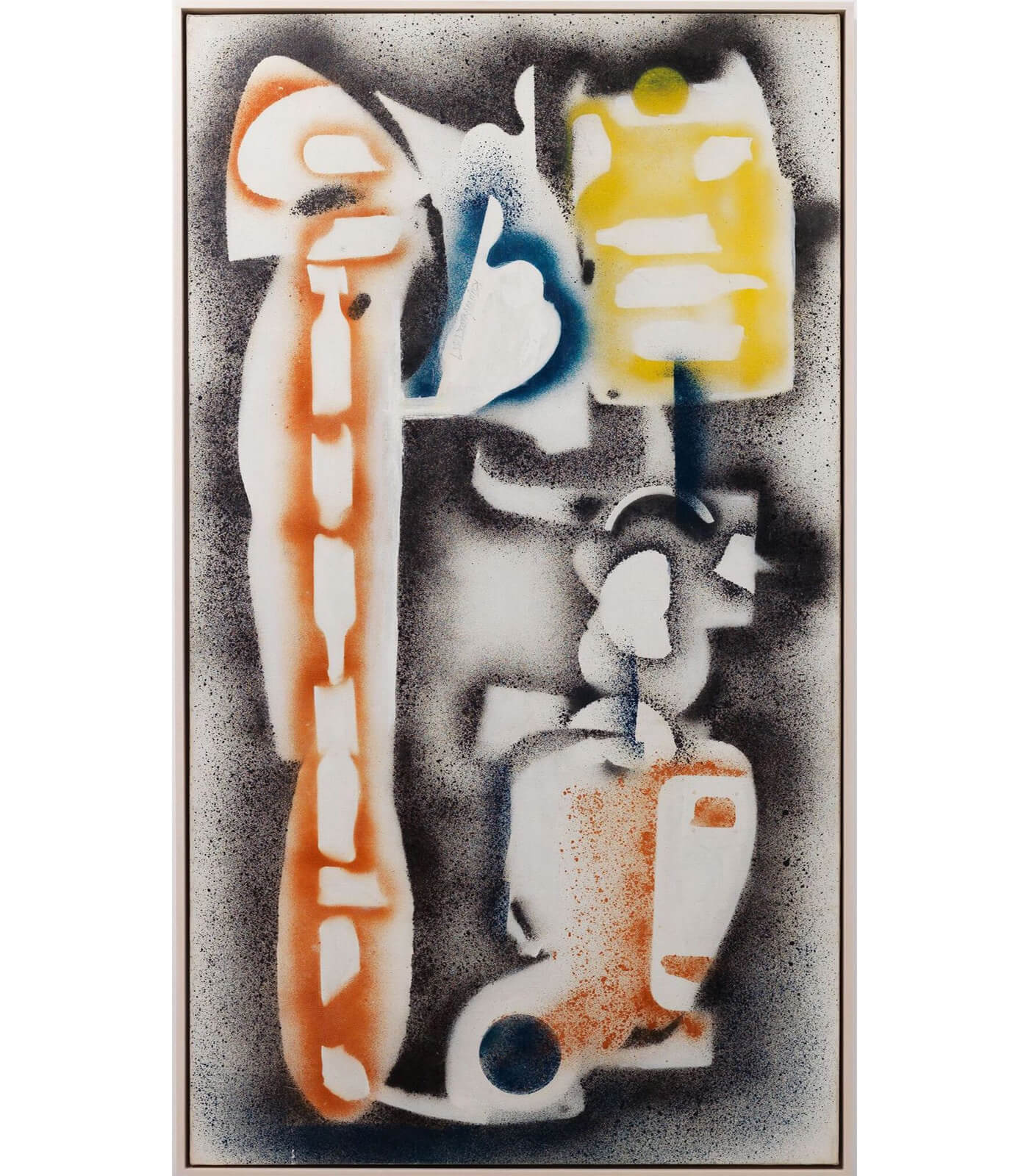

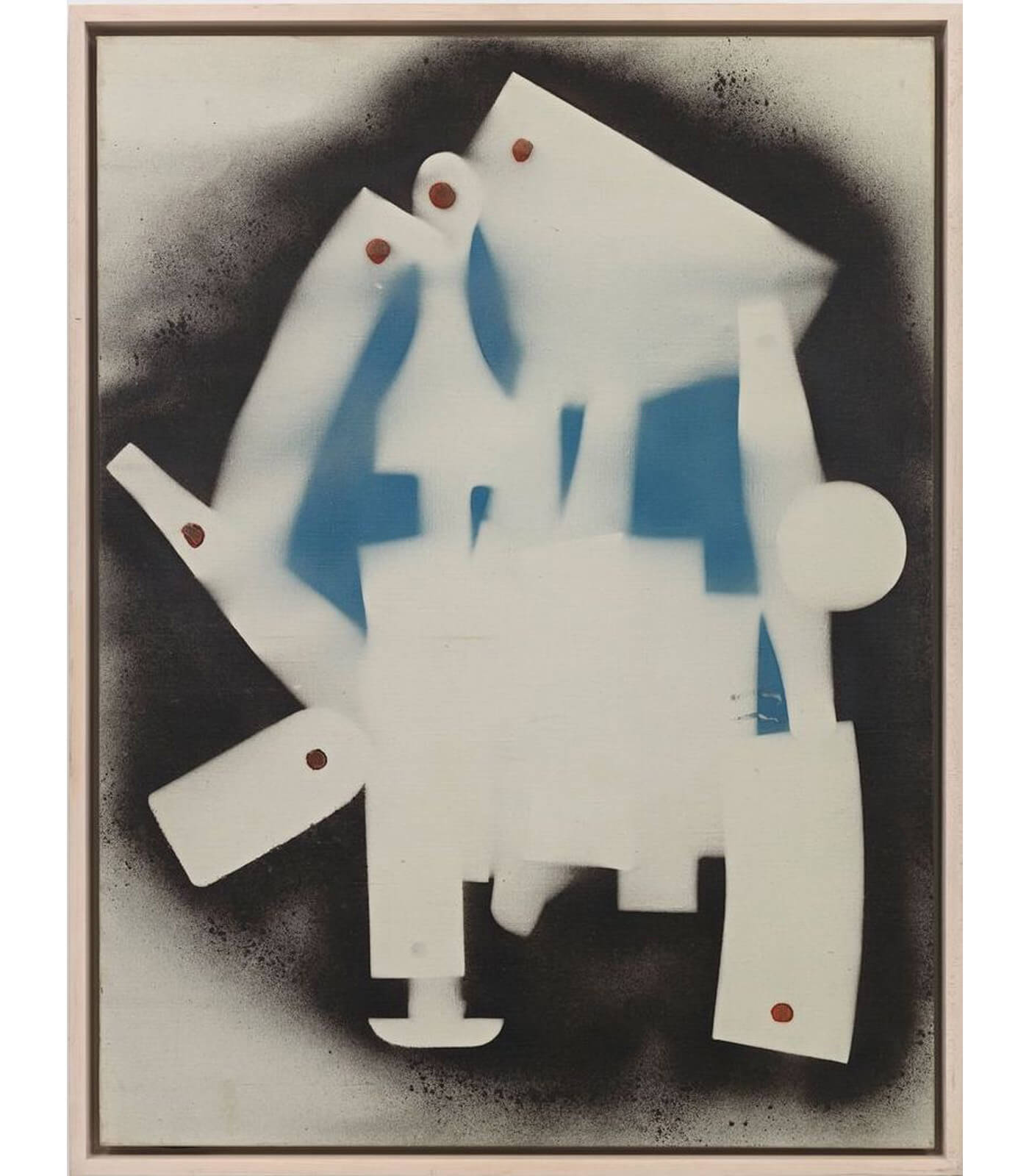

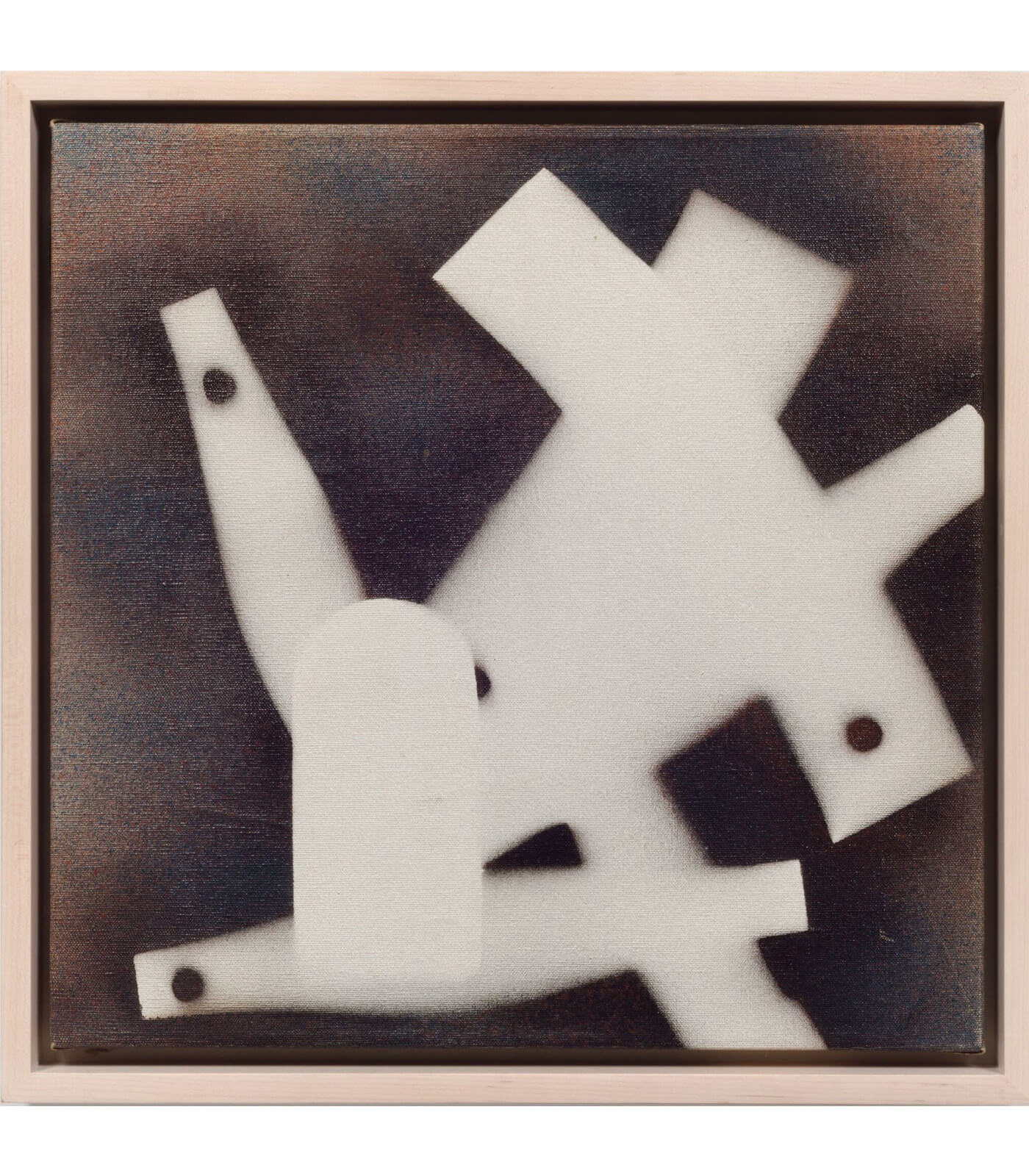

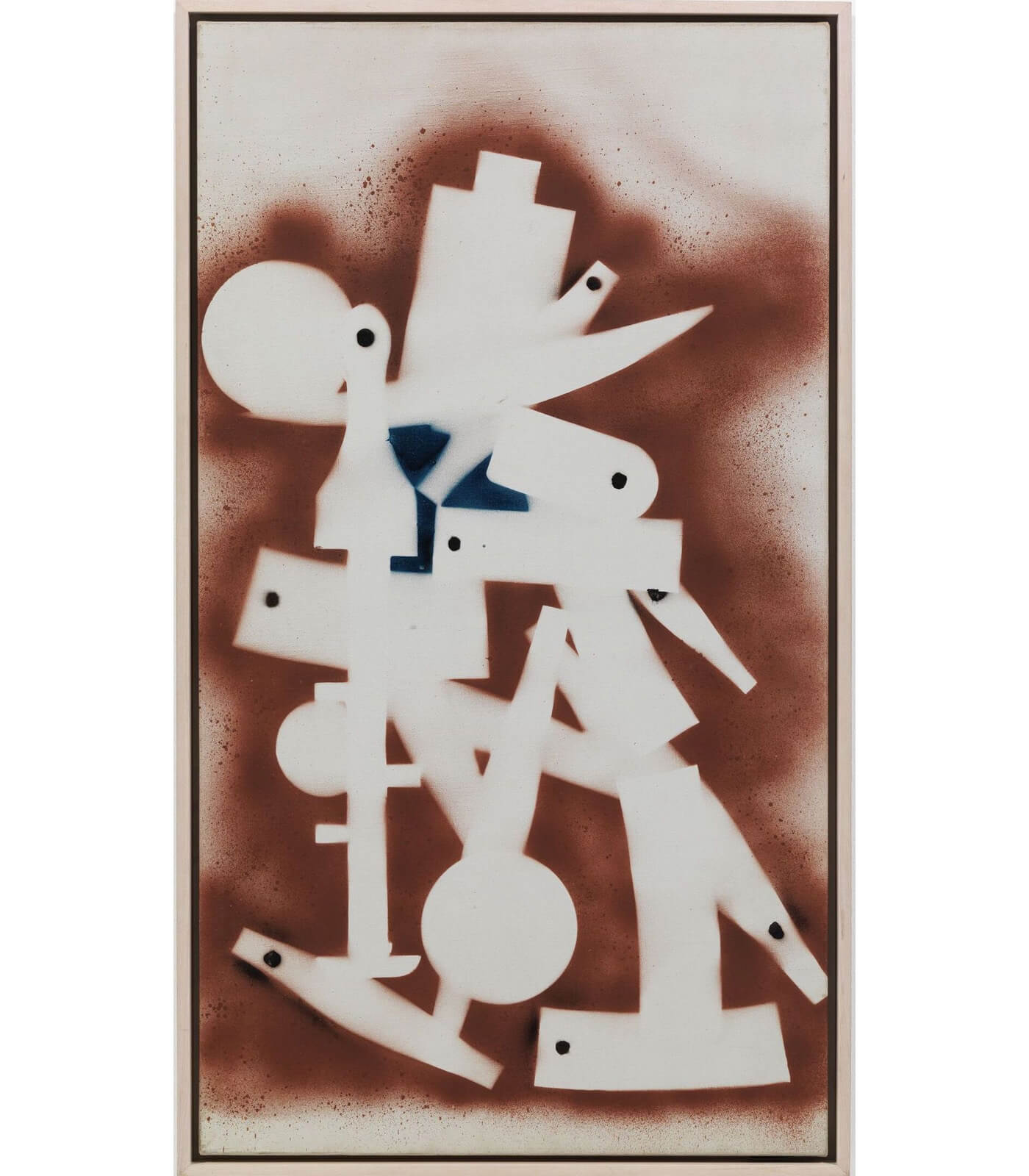

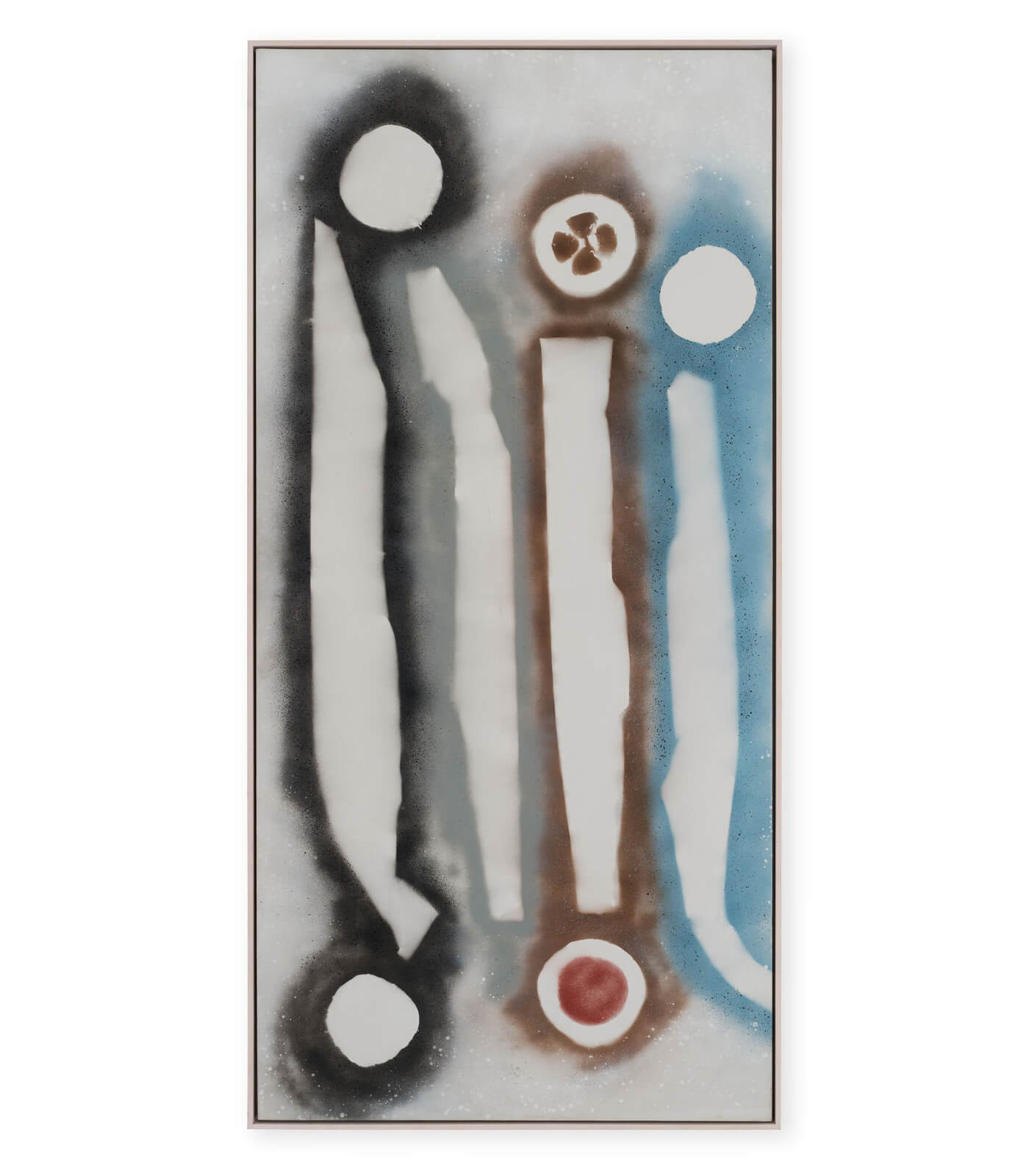

When creating a sculpture, Smith would often place components of the work in progress on white-washed areas of his shop floor, before joining them together. The welding scorched the floor, leaving ‘ghost’ images of the sculpture. Inspired by these incidental patterns, Smith began work on the Sprays, employing any material at hand, from machine parts to tree branches, and even leftovers from his table, which he arranged on paper or canvas before spraying over the composition with industrial enamel paint.

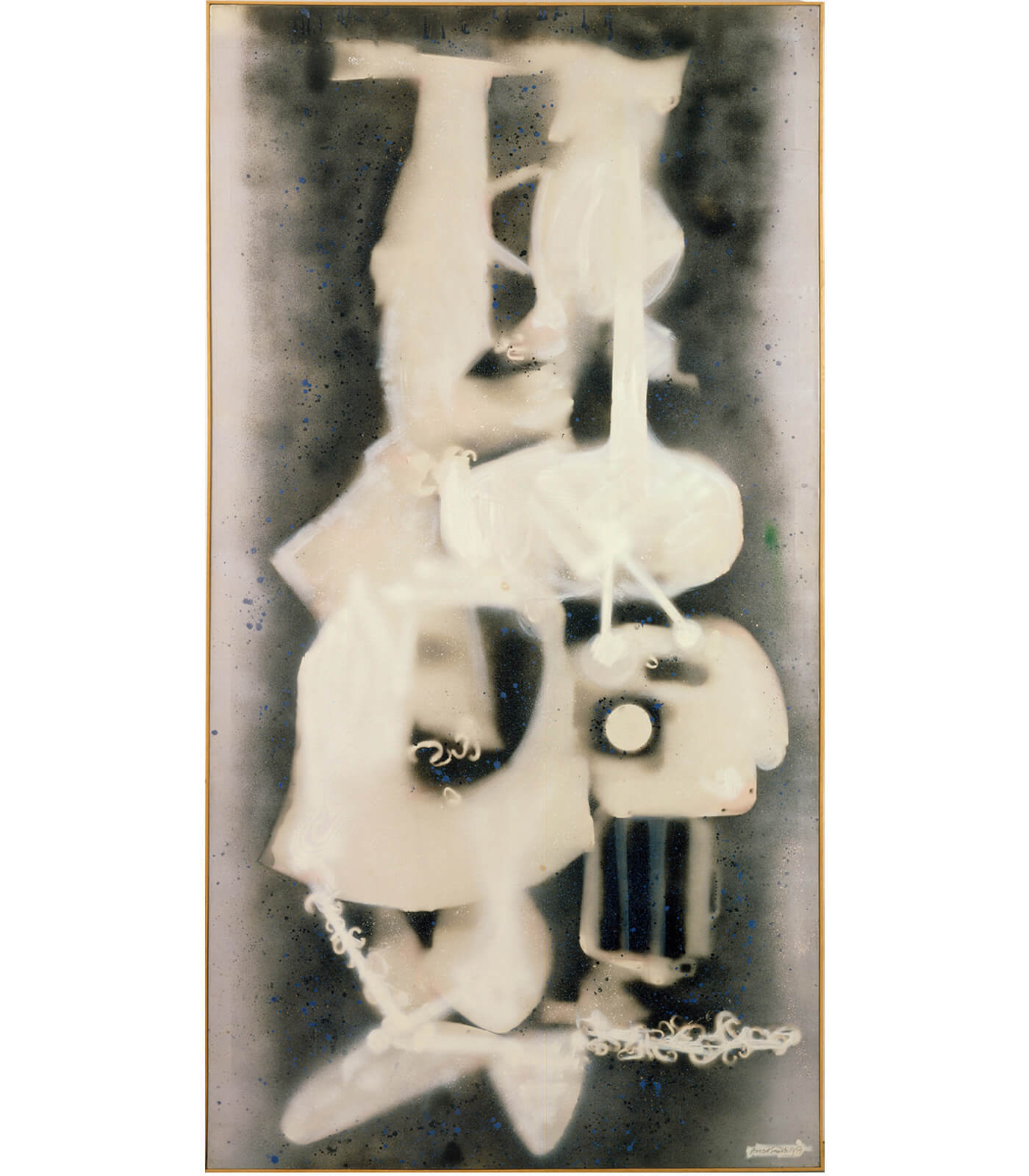

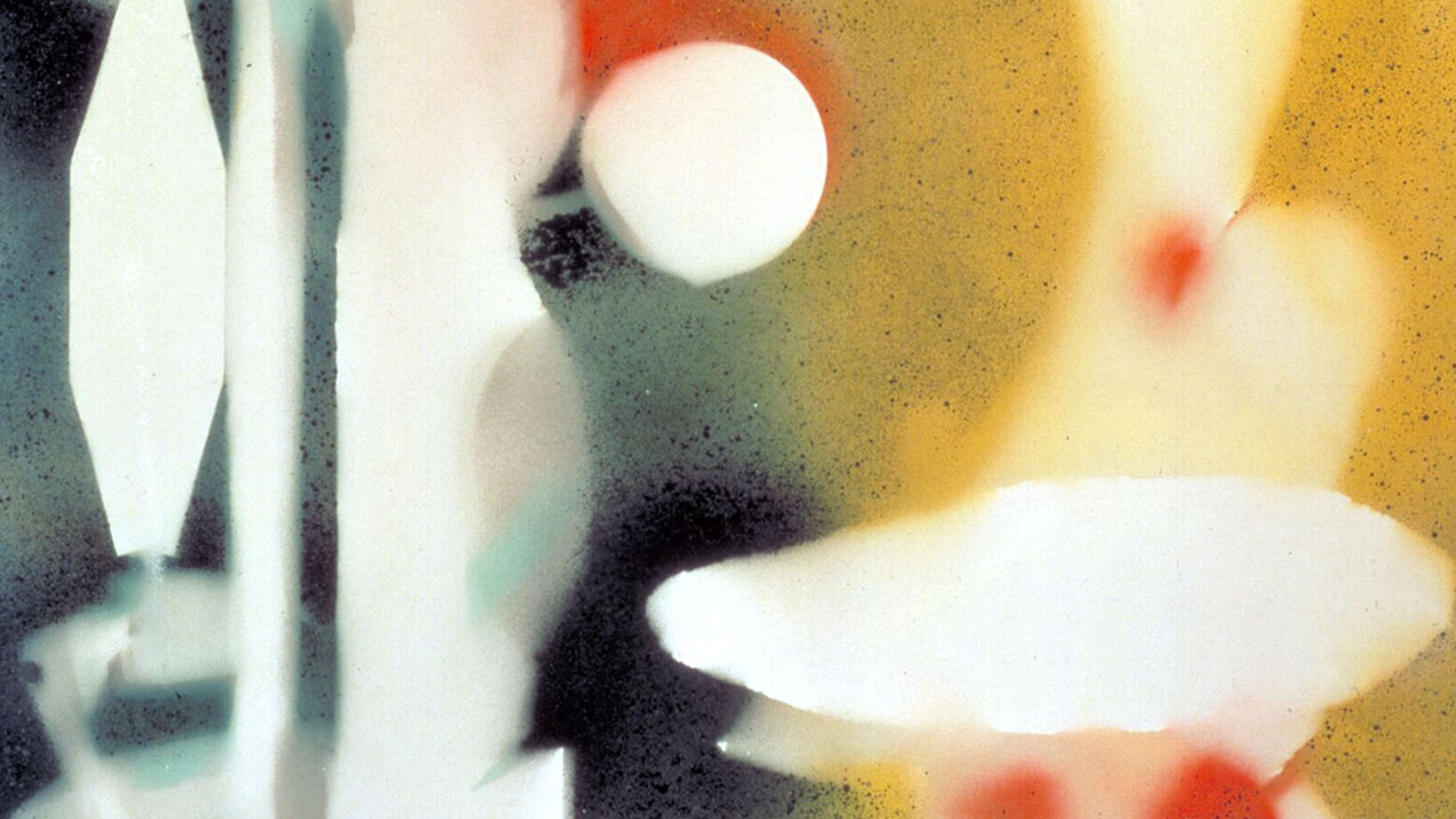

When the objects were removed, their silhouettes remained, sometimes with hazy outlines from the diffused paint that seeped beneath the objects’ edges. The Sprays can feature bold forms in complex rhythms against misty backgrounds that have been likened to a celestial expanse. They express the ambiguity between positive and negative space, contrasting layers of effervescent colour with areas of white. Shapes can appear weightless, sometimes clustering together and at other times moving apart amidst the sprayed pigments.

Phyllida Barlow on the Sprays

‘What do these empty spaces become? The fuzz of spray precisely boundaried by its surgical edge – an incision abutting the exposure of blank surfaces, seemingly unfilled. Cezanne’s watercolors reveal similar conflicting realities: raw canvas, raw paper, and sprayed, painted surfaces in competition, but united by athletic accuracy, harmoniously transformed into mass, light, space, terrain, posture; time, speed and action forever trapped’.—Phyllida Barlow, July 2020.

Clare Lilley on the Sprays

Curator and Director of Program at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Clare Lilley traces Smith’s Sprays from 1957, after car aerosol paint became commercially available. For Lilley, this series holds significance to Smith’s overarching thematic preoccupations, as they relate to the human form, the landscape, and his sculptural practice.

Smith debuted the large-scale Sprays in New York in Fall 1959. Dr. Field writes about the significance of these works: ‘‘The Sprays’ imposing heights align them with the monumental scale that had become a defining characteristic of abstract expressionist and color field painting. The Sprays also connect Smith’s painting practice to a new generation of artists who were engaged with issues having to do with the use of found materials (including mass-produced, or readymade, pigments) and mechanical techniques.’

Dr. Jennifer Field on the Sprays

In the late 1950s, David Smith began laying down large sheets of canvas on his workshop floor, arranging objects on them, spraying enamel paint from aerosol cans on and around the objects, then removing them from the surface, leaving behind silhouettes of varying shapes intertwined with vibrantly colored passages. This technique yielded the dynamic body of work represented in this exhibition. Commonly referred to as ‘Sprays,’ it redefined Smith’s painting practice and helped to revolutionize the very notion of what constituted fine art painting.

Spray enamel was a new medium, only recently available on a commercial basis—and one that was associated with industrial manufacturing. There was no precedent for using it as an artistic medium. That would not have deterred Smith, who, though trained as a painter at the Art Students League, would deploy the technical knowledge he absorbed working in automotive and locomotive factories to construct welded metal sculptures. In preparing to make a large sculpture at his home in Bolton Landing, Smith would whitewash rectangular areas on his shop floor, lay out metal fragments and arrange them into a desired composition, and weld them together using an acetylene torch. When the sculpture was raised, the scorched outlines of the shapes were left behind on the white floor, an ephemeral record of Smith’s process.

In the Sprays, Smith adapted this technique to painting. He would develop a large canvas as a kind of palimpsest; the materials he laid out—which could include metal or paper fragments, or organic debris—varied in opacity and size, yielding overlapping planes of different colors and degrees of translucency. Often, he would highlight exposed areas of the canvas by brush with white paint to accentuate tonal contrast. Shapes appear weightless, floating in space, sometimes clustering together and at other times moving apart amidst the sprayed pigments. The result is a shifting sense of spatial depth in an atmosphere that has been likened to a ‘celestial’ expanse or a landscape—associations that are amplified by the grand height of the large Sprays, which measure eight- to nine-feet tall [1].

Smith debuted the large Sprays in New York in Fall 1959 at French & Company, a distinguished Upper East Side gallery that had recently hired Clement Greenberg as an adviser for a new top-floor exhibition space for contemporary art [2]. The Sprays’ imposing heights align them with the monumental scale that had become a defining characteristic of abstract expressionist and color field painting.[3] The Sprays also connect Smith’s painting practice to a new generation of artists who were engaged with issues having to do with the use of found materials (including mass-produced, or readymade, pigments) and mechanical techniques. Indeed, Smith’s Sprays would have seemed at home in the groundbreaking 16 Americans exhibition that opened that December at The Museum of Modern Art, and which featured works by Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Rauschenberg, and Frank Stella. Appropriate to this art-historical moment, one review of the French & Company exhibition lauded the ‘radical’ nature of Smith’s ‘enormous’ canvases, while another critic was bothered by the very features that would drive avant-garde concerns, namely the lack of authorial gesture conventionally signified by the touch of a brush to canvas.[4]

Smith once described his transition to sculpture-making as ‘constructions leaving the canvas.’[5] The Sprays demonstrate Smith’s ability to, inversely, generate a unique and animated body of flat works from a three-dimensional matrix. Smith had investigated the illusionistic effects of transposing volumetric objects to a flat surface in the early 1930s, when he experimented with unconventional photographic techniques. These included double-exposing negatives to produce overlays of patterns and forms, and creating photograms by arranging elements onto photosensitive paper then exposing it to light, leaving ghostly silhouettes where the objects once lay.[6] Smith toggled between mediums and styles at the same time. While making the Sprays on canvas he produced a large number of Sprays on paper the size of a sketchbook page. Despite their small scale, these works bear a close structural resemblance to Smith’s sculptural assemblages, with inherent geometry and gravitational weight toward the bottom of the sheet, where Smith would sometimes suggest a base or horizon line.

In 1963 Smith began a campaign of medium-sized Sprays on canvas in a range of formats and sizes, which can be seen in the second gallery of this exhibition. These paintings were based on arrangements of machine shop templates, with holes for hanging, which can be seen in the final compositions. Recalling his experience working in a Studebaker factory in South Bend, Indiana, Smith once stated that he considered all the parts he manufactured to be ‘abstract,’ their functions obscured by the compartmentalized nature of mass manufacturing.[7] In the medium Sprays, Smith exploited the abstract nature of such elements. The contours of the templates are more clearly defined than the shapes seen in the large Sprays, yet they remain just as enigmatic, assembled into elegantly choreographed compositions against misty, multi-hued backdrops.

[1] Trinkett Clark, ‘The Sprays,’ in The Drawings of David Smith exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1985), 31. [2] The exhibition, titled David Smith: Paintings and Drawings, took place from September 16-October 10, 1959. It featured twenty-two large Sprays and over thirty of Smith’s calligraphic ink drawings. [3] Barnett Newman’s canvases, including the large paintings Cathedra and Vir Heroicus Sublimis, had been the subject of the inaugural exhibition at French & Company in Spring 1959. [4] Emily Genauer, ‘Two Leading Artists Show Radical Change,’ New York Herald Tribune (September 20, 1959), Section 4, 7; Sidney Tillim, ‘Month in Review,’ Arts Magazine 34, no. 1 (October 1959), 49. [5] David Smith, ‘The Modern Sculptor and His Materials’ (1952) in Susan Cooke ed., David Smith: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Interviews (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 157. [6] For more on relationship of Smith’s photographic practice to the Sprays, see Peter Stevens, ‘Sprays: The Absent Object,’ in David Smith: Sprays (New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2008), 99-103. [7] David Smith, ‘The Concept is Primary’ (1938-39) in Cooke, 26.

David Smith talks to Frank O’Hara

In this excerpt from ‘David Smith: Sculpting Master of Bolton Landing’, David Smith discusses the role of paint and color in his sculptures with the poet, writer and art critic, Frank O’Hara. The interview was first aired by Channel 13/WNDT-TV, on 11 November 1964 as part of the series ‘Art New York.’

‘My sister and I would hear the particular rattle of his spray cans as he made paintings to jazz records. I see in these works a great sense of what I knew of my father - his love of making and constructing form’. —Rebecca Smith

Painting and drawing remained integral to Smith’s creative output throughout his career. ‘Drawings,’ he claimed, ‘are studies for sculpture, sometimes what sculpture is, sometimes what sculpture never can be.’ Since David Smith’s tragic death in 1965, he has continued to inspire contemporary artists. The Sprays reflect Smith’s unique ability to convey a deeply humanist vision through an abstract vocabulary.

Installation view, 'David Smith. Form in Colour', Hauser & Wirth Zürich, 2016 © The Estate of David Smith

About the artist

One of the foremost artists of the twentieth century and the sculptor most closely linked to the Abstract Expressionist movement, David Smith is known for his use of industrial methods and materials, and the integration of open space into sculpture. Over a 33-year career, Smith greatly expanded the notion of what sculpture could be, questioning its relationship with the space it was created in and its final habitat. Spanning pure abstraction and poetic figuration, Smith’s deeply humanist vision has inspired generations of sculptors for the decades since his death.

Inquire about other available works by David Smith

David SmithSprays

With thanks to contributing museums: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Harvard Art Museums/ Fogg Museum, Cambridge, MA; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC; Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas; The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/de Young Museum, San Francisco; The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

–

Under the umbrella of Hauser & Wirth’s new global philanthropic and charitable initiative #artforbetter, we are donating 10% of gross profits from sales of all works in our online exhibitions to the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund for the World Health Organization.

Images from top:

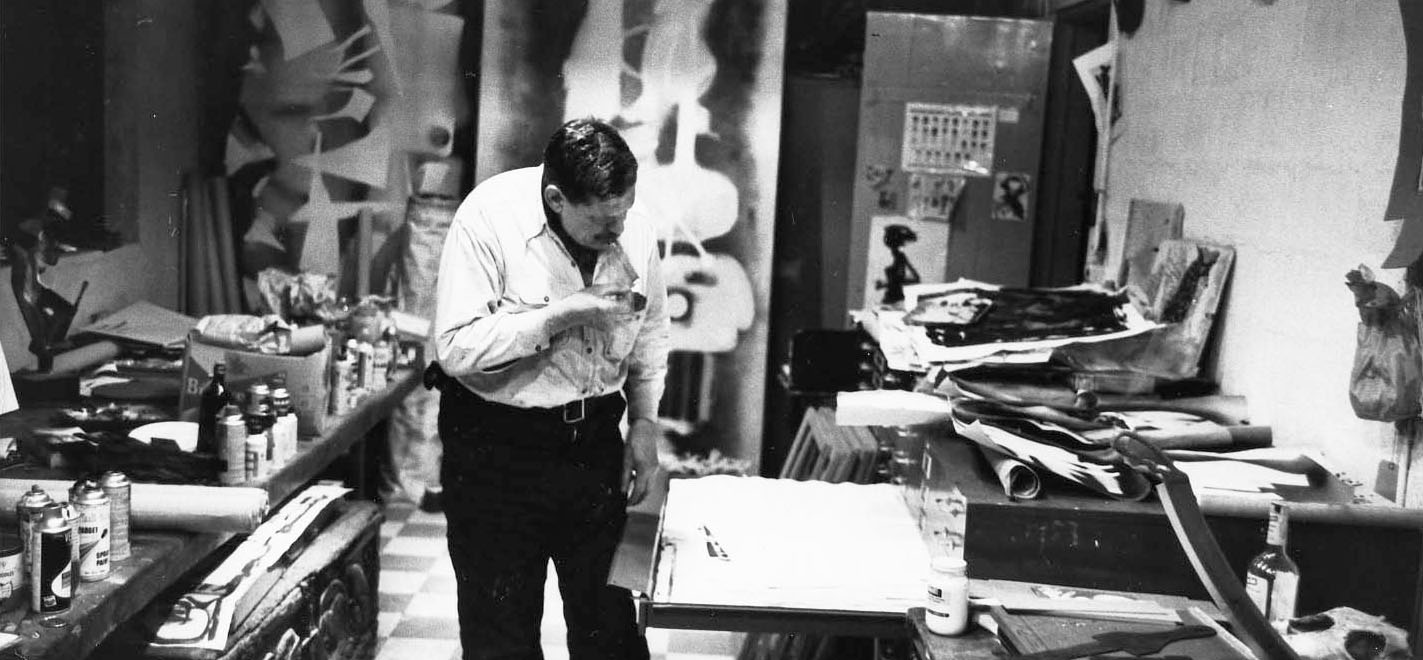

David Smith in his drawing studio with Head (1932), Becca Running (1958), Untitled (1959), Untitled (1959), Bolton Landing, NY, c. 1962. Photo: Dan Budnik © 2020 Dan Budnik. All Rights Reserved; David Smith, Elements for Albany II (1959), Land Coaster (1960), Untitled (1960), and Doorway on Wheels (1960) on the workshop floor, Bolton Landing, NY, c. 1959. Photo: David Smith © 2020 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; VR Installation view from left to right: Circle and Parts on Central Column (1959), Quixote Don (1958-1959), Red Heart (1959); David Smith, Two Circles on Yellow and Green, 1959 (detail), Loan from Raymond and Patsy Nasher Collection, Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas, US. Photo: David Heald; VR Installation view from left to right: White Egg with Pink (1958), Untitled (1959), Untitled (1963), Untitled (1959); VR Installation view from left to right: Untitled (1959), Untitled (1959); Installation view, ‘David Smith. Form in Colour’, Hauser & Wirth Zürich, 2016 © The Estate of David Smith; The artist in his studio, 1951 at Bolton Landing, New York. Photo John Stewart; David Smith. Elements for Study in Arcs (1959) laid out on the workshop floor with Untitled (1955) and two Untitled paintings (1957), Bolton Landing, NY, c. 1957. Photo: David Smith © 2020 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

All images © 2020 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY