Essays

Toward the Act of Knowing

Recollections of Eduardo Chillida, in honor of his centenary

By Use Lahoz

Translated from the Spanish by Ania Hull

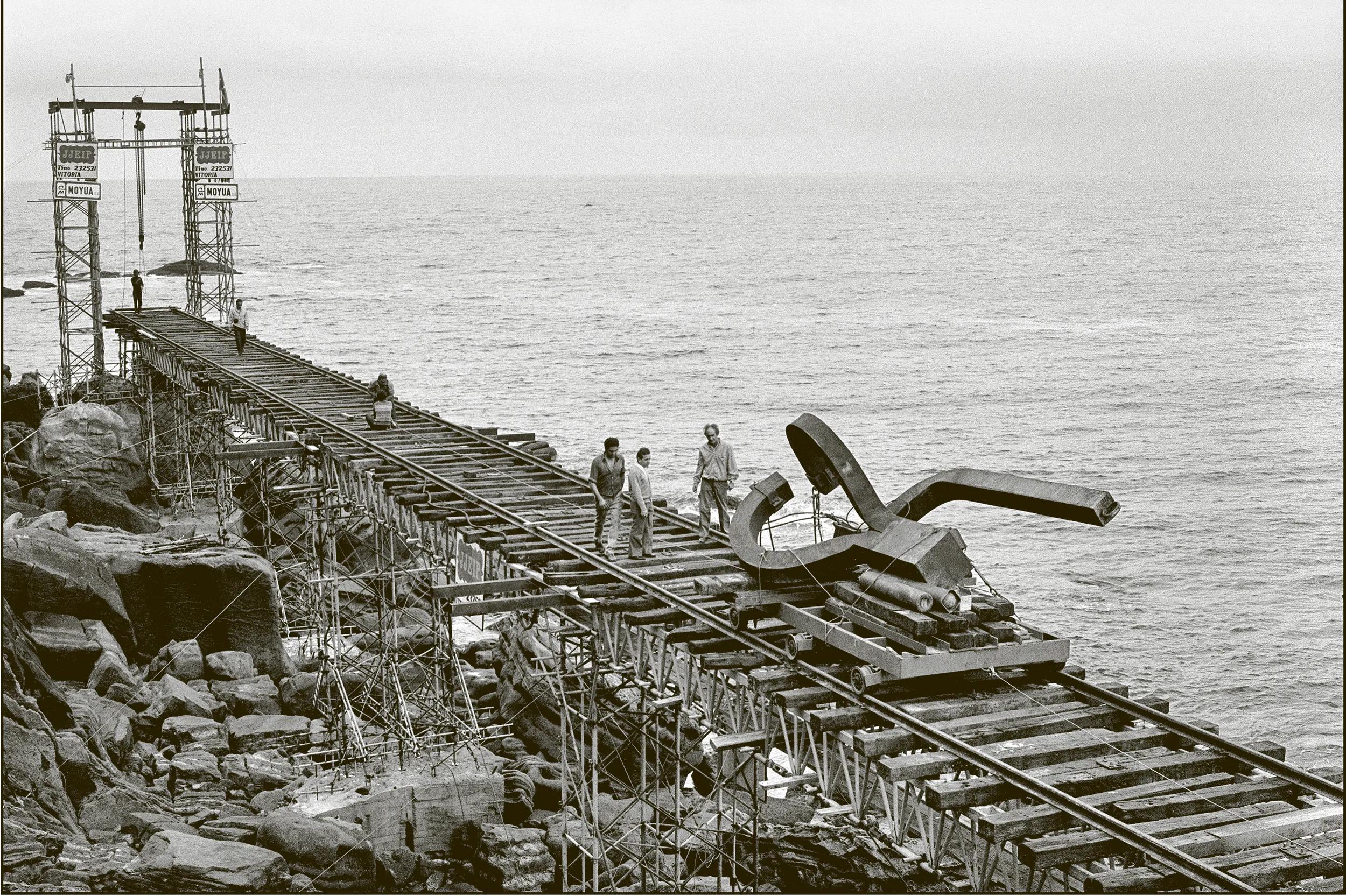

View of Eduardo Chillida's Peine del viento XV (Comb of the Wind XV),1976, San Sebastián, Spain. Photo: Francesc Català-Roca © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VEGAP, Madrid

Recognized for his monumental iron and steel public sculptures, Eduardo Chillida (1924 – 2002) is among the most revered Spanish sculptors of the 20th century. He called himself an “architect of the void,” and his attention to negative space permeates the spirit and body of his work. A landmark of his artistic legacy is Chillida Leku (“Chillida’s Place,” in his native Basque)—a twenty-seven-acre, open-air museum he developed with his wife, Pilar, where more than forty sculptures stand in harmony with the surrounding Basque landscape.

Chillida would have been one hundred years old on January 10, 2024. His centenary is accompanied by the yearlong initiative “Eduardo Chillida 100 Years,” led by the Eduardo Chillida—Pilar Belzunce Foundation, which includes major presentations at Chillida Leku and Hauser & Wirth Menorca. On the occasion of this celebration, writer Use Lahoz interviewed several members of Chillida’s inner circle, including family, friends and collaborators. Their recollections and observations are compiled here into a new essay about his life and his influential quest to unite nature and art.

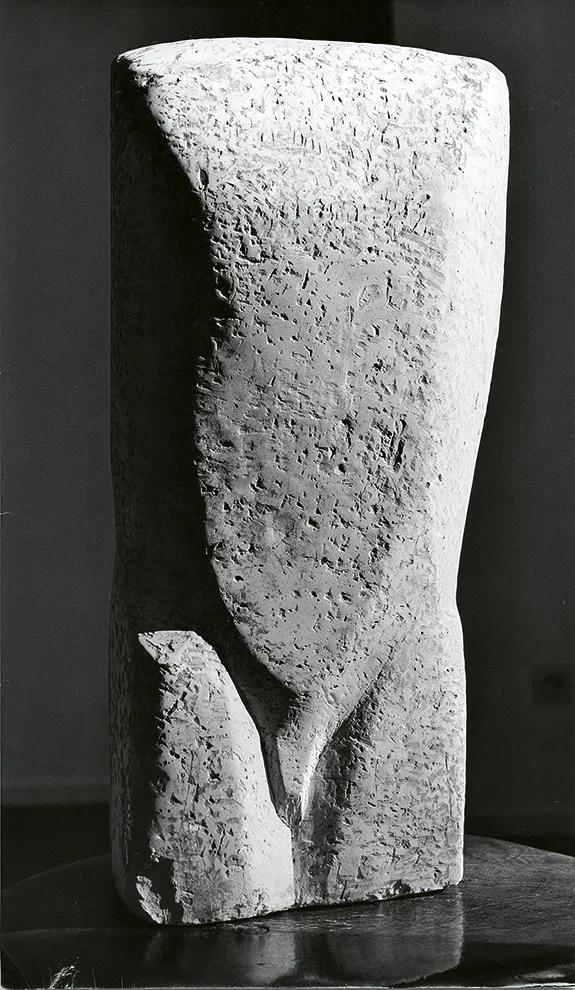

Eduardo Chillida, Torso, 1948. Artwork by Eduardo Chillida courtesy the Estate of Eduardo Chillida and Hauser and Wirth

Eduardo Chillida, Proyecto Tindaya, 1995 (sculptural maquette for the proposed and ultimately unfulilled Tindaya project). Photo: Jesús Uriarte. © Zabalaga-Leku. ARS, New York / VEGAP, Madrid. Artwork by Eduardo Chillida courtesy the Estate of Eduardo Chillida and Hauser and Wirth

In 1950, after two years at the Colegio de España in Paris, Eduardo Chillida said, in a moment of weakness, “Pili, I’m done.” Pilar Belzunce, his soon-to-be wife, corrected him. “No,” she said. “The thing is, you haven’t even started yet.”

Soon after, Chillida rejected what he had produced up until that point: sculptures in plaster and terracotta, torsos influenced by Greek antiquity. Though Chillida had a torso on view at the Salon de Mai in Paris—his first artwork selected for an exhibition—the acclaim it won left him cold and dissatisfied. In 1951, he returned to his homeland in the Basque country to, in his words, “gently watch the grass grow,” reflecting, reading and working to outgrow his early artistic boundaries.

In his writings, Chillida said, “Limits that are seemingly impossible to reach are crucial to me; without them I would see the world as flat.” With this resolve in mind, he ultimately manipulated steel into the massive rhythmic forms of Peine del viento XV (Comb of the Wind XV)(1976). Located in the bay of La Concha in San Sebastián, the steel forms blend with elemental forces, uniting earth, sea and air. This sculpture and the Chillida Leku site, outside the town of Hernani, are regarded as two of his greatest achievements. Like Chillida, they are Basque to the core and without limits or borders.

“It was always easy to know where Eduardo was: working.”—Jesús Uriarte

“The first direct contact I had with Chillida was during the installation of Comb of the Wind,” says photographer Jesús Uriarte, who had known Chillida as a patron of Casa Cámara, Uriarte’s family restaurant, an establishment frequented by Ernest Hemingway, Orson Welles, Deborah Kerr, and other notable regulars. Upon seeing the eighty-meter temporary walkway that had been constructed for the installation, Uriarte recalls, “I thought of the movie The Bridge on the River Kwai. It seemed like a crazy and risky idea—but graphically wonderful—to set up that walkway in the Cantabrian Sea in the middle of September, with spring tides, and transport a ten-ton sculpture above the waves.”

Uriarte began collaborating with Chillida in 1983, photographing the artist’s works and documenting the process of many of his public sculptures. “Eduardo spent the mornings in his studio or the small forge,” Uriarte says. “At noon, he’d visit the Zabalaga farmhouse in Hernani, where he’d meet with Pili and Joaquín Goicoechea, a dear friend who was instrumental in making Chillida Leku a reality. It was always easy to know where Eduardo was: working.”

Architect Rafael Moneo, a longtime Chillida collaborator, says of Comb of the Wind that “the careful and precise name Chillida gave to this work—which he wanted to bear witness to his life in San Sebastián in front of his sea—echoes the personal and site-specific nature of the work. The wind as time, the comb unperturbed before it, anchored to a rock where Eduardo, I suspect, must have spent many hours sitting.” Anita Feldman, deputy director of curatorial affairs at the San Diego Museum of Art, which will present a major Chillida exhibition in 2025, adds that Comb of the Wind still resonates six decades after its creation. “It combines the strength of the surfaces of Corten steel, with views of the changing sea and sky, the smell of the ocean, and the sound of the waves breaking and receding. The hollow channels carved into the stone below the visitor’s feet produce musical whistles or surprising bursts of sea spray depending on the tides.”

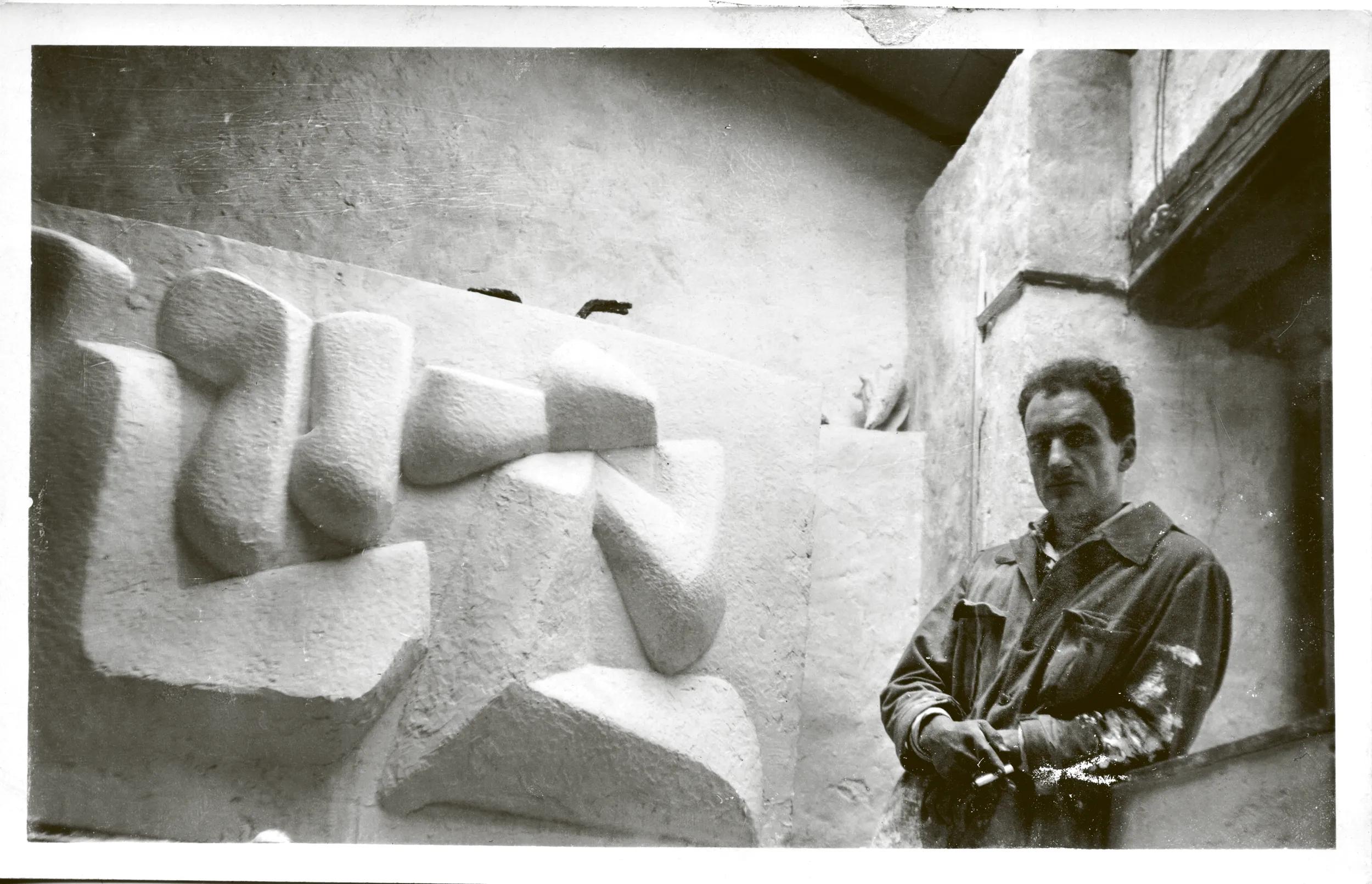

Chillida in Paris with Mural Atoxta Villaines, 1951. Artwork by Eduardo Chillida courtesy the Estate of Eduardo Chillida and Hauser and Wirth

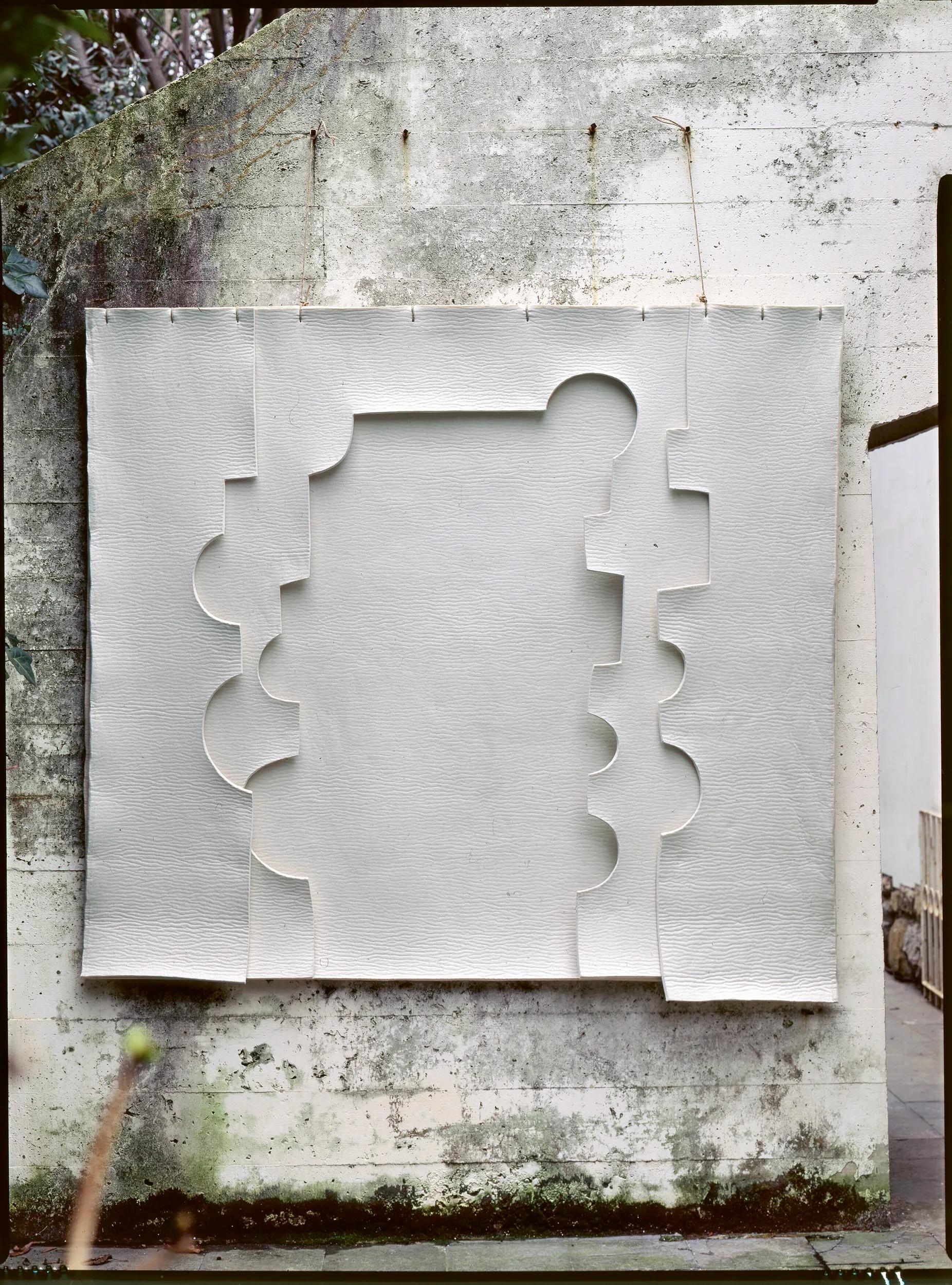

View of Eduardo Chillida, Gravitación Fieltro, 1990, at Chillida Leku, Hernani, Spain. Artwork by Eduardo Chillida courtesy the Estate of Eduardo Chillida and Hauser and Wirth

Describing Chillida Leku—a museum that doubles as art itself, where beeches and oaks coexist with steel and granite—Chillida said: “I once dreamed of a utopia, of a space where my sculptures could rest, and where people could walk among them as though through a forest.”

Architect Joaquín Montero, who met Chillida in 1973 and became a dear friend, was key to the materialization of this dream. The pair ultimately collaborated on eleven projects together in Paris, Helsinki, Munster, Lausanne and Whitehaven, England. He recalls how, after three years of observation and doubt, he and Chillida decided to keep the Zabalaga farmhouse bare inside, as it was “already an empty space produced by deterioration.”

Montero remembers another curious detail of Chillida’s commitment to reflection and self-improvement: “Eduardo recognized early on that he could draw quite easily with his right hand. Later, he realized that this facility probably kept him from doing things with greater depth. His right hand not only did not help him—it also hindered him. And so he made a decision that would mark his life and career forever: to draw only with his left hand.” From then on, he noticed that his voluntary clumsiness forced his mind to spring into action before his hand joined in.

Chillida with soccer team Real Sociedad, 1943 (pictured back row, center).

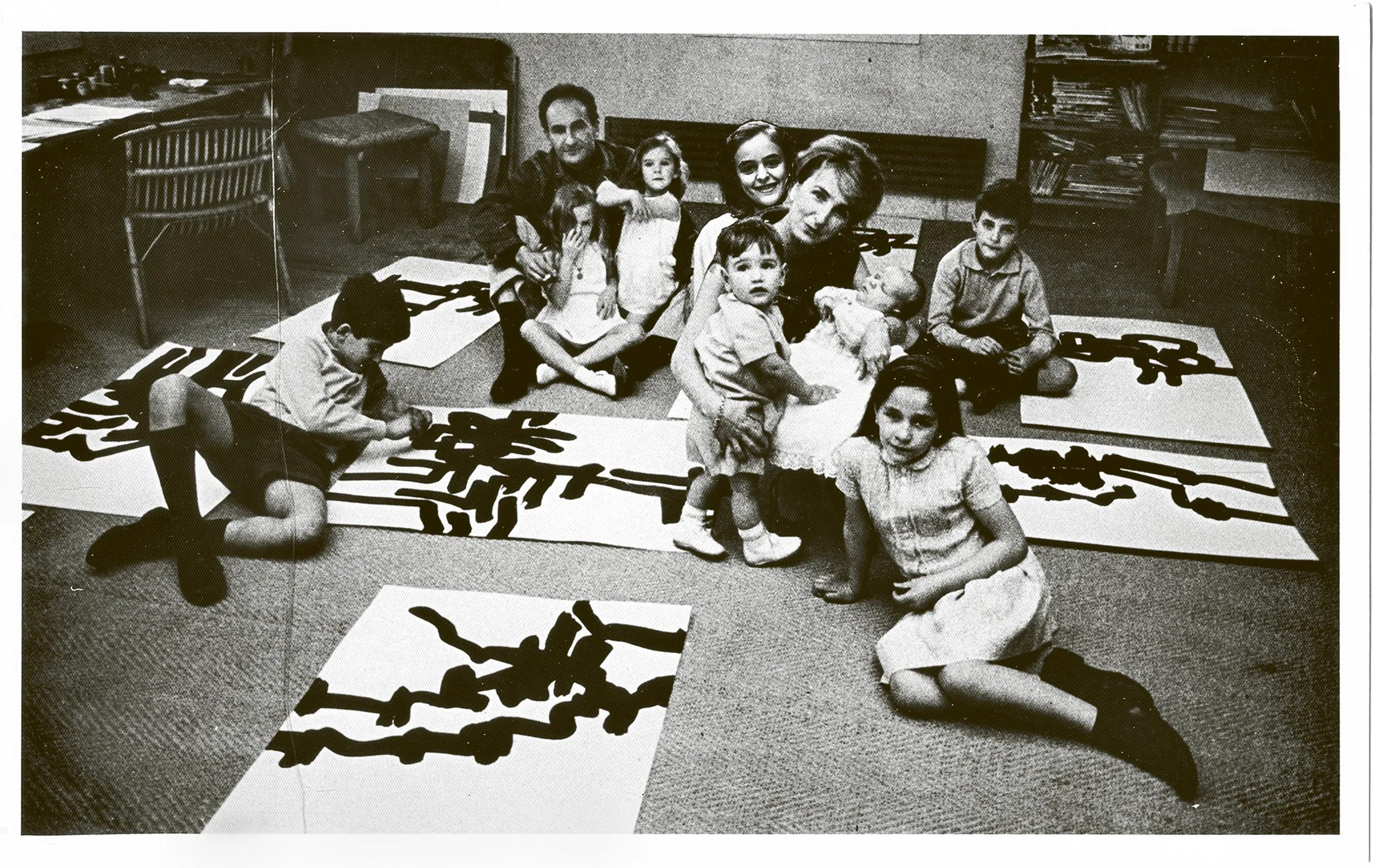

Chillida family portrait in Villa Paz, 1963. Photo: Budd Studio

“During a match in Valladolid, an opposing player broke my father’s knee, and he had to quit soccer. My mother used to tell me that whenever she’d go shopping in the old town of San Sebastián, everyone would stop her to say, ‘Oh, what would have become of your husband had he not been injured?’ But that player did him a favor in the end.”—Ignacio Chillida

The Basque curator Peio Aguirre emphasizes that Chillida’s sculptural work existed hand in hand with his works on paper. “The close, formal relationship between his sprawling graphic work (drawings and prints) and his sculptures is obvious,” Aguirre says. “The morphology in both shows similarities that indicate that he first thought in two dimensions before tackling the third. However, his graphic work, being of a reproducible medium, dispels the aura and mysticism that surround his sculpture. When his work moves to mass reproduction in posters and logos that lend themselves to different designs and applications, Chillida reaches the popular and infiltrates the collective memory.” Aguirre continues, “His political commitment to different humanitarian causes in the ’70s and ’80s was unmistakable: freedom of expression, amnesty for political prisoners. He was against terrorism and for peace. He was against the nuclearization of the Basque coast. These social struggles took on a ‘Chillidan’ visual identity.”

Chillida’s son, Ignacio, who worked as his father’s studio assistant, remembers, “My father started with plaster and wood and moved to iron when he and my mother left Paris and settled in Hernani, in the house his mother had left him. The house was called Vista Alegre [“Joyful View”]. Everything that happened after that did so because of a forge that stood opposite this house, with a workshop full of mechanical things for factories. There, my father worked with a blacksmith whom he had asked to teach him.”

“When we were children and lived in Villa Paz, in San Sebastián, he’d make us go up the hill every day, to the fronton, to play soccer before lunch,” Ignacio says of his father. “He was very skilled. When he was still the goalkeeper of the soccer team at the Marianist school, they called him one day to tell him that they needed him as goalkeeper for Real Sociedad, a first division team of which his father, my grandfather, was the vice president. My father became the team’s starting goalkeeper. But then during a match in Valladolid, an opposing player broke my father’s knee, and he had to quit soccer. My mother used to tell me that whenever she’d go shopping in the old town of San Sebastián, everyone would stop her to say, ‘Oh, what would have become of your husband had he not been injured?’ But that player did him a favor in the end.” The principles of soccer, however, stayed with Chillida long past his playing days. The artist himself described the necessary abilities shared by the goalkeeper and the sculptor—intuition, spatial awareness and the use of the hands. Peter Murray, founder of the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in the U.K., which has exhibited Chillida’s work, says, “Like Chillida, my father had been a goalkeeper in his youth. Chillida and I talked about soccer and what he had learned about space when he had played for Real Sociedad. We talked about the landscape as a place for sculpture, and he became fascinated with the English landscape of Yorkshire. The time I spent at Chillida Leku influenced the choreography of the Yorkshire Sculpture Park exhibition.”

Eduardo Chillida, Elogio del agua, 1987, Barcelona. Courtesy the Eduardo Chillida Archive

View of Chillida Leku, 1990. Photo: Robert B. Fishman/Alamy. Artwork by Eduardo Chillida courtesy the Estate of Eduardo Chillida and Hauser and Wirth

Susana Chillida, a scholar and documentarian of her father’s work, remembers him as “a loving man who liked to play with us children.... He adored the innocence of little ones, their fresh gaze, their trust,” she says. “Later, when I approached him with my cameras hoping to understand his work better, he welcomed me with open arms into the intimacy of those places no one had ever filmed before. My work brought us closer. I easily switched from my role as filmmaker to that of a loving daughter, so as to bring out in him the authenticity I knew so well. The only thing he told me at the beginning was, ‘Follow your intuition.’ And occasionally, he would check and say, ‘Are you doing what you set out to do?’”

Although he first showed his work at the dealer Aimé Maeght’s gallery in Paris in 1950, it wasn’t until 1954 that Chillida joined Galerie Maeght’s roster of artists. By then, Aimé was already a close friend and, thanks to this connection, Chillida had direct contact with the likes of Braque, Miró, Calder and the philosopher Gaston Bachelard, who wrote for Chillida’s first catalogue with the gallery. Until Aimé’s death in 1981, Eduardo and Pili would spend their summers at his house in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. Isabelle Maeght, his granddaughter and the current director of the gallery, says, “Eduardo Chillida was the youngest artist on show at the inauguration of the Marguerite and Aimé Maeght Foundation in July 1964. One of his huge wooden sculp- tures occupied a prominent place in the largest room. It made a strong impression, standing there surrounded by masterpieces by Georges Braque, Alberto Giacometti, Vassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall and Joan Miró. Eduardo’s arrival every summer in Saint-Paul with Pili and their children allowed us to gather as a family: the Maeghts, the Mirós, the Artigas, the Chillidas, the Bazaines, the Riopelles.... Several generations came together. What wonderful days we spent together!"

Installation of Chillida’s Comb of the Wind XV, 1976, San Sebastián, Spain. Photo: Jesús Uriarte. Artwork by Eduardo Chillida courtesy the Estate of Eduardo Chillida and Hauser and Wirth

In an essay, Chillida noted that “art is learned, not taught.” He came to understand any work of art as a step, or an aid, to seeing what remained in the shadows: “Experience points toward knowledge; perception toward the act of knowing.” In Susana Chillida’s documentary Chillida: Arte y Sueños [Art and Dreams] (1999), her father told her that he had been interested in the idea of perception even as a child: While playing, his father would lock young Eduardo and his siblings in a dark room and after a few minutes invite them to come out and explain to him what they had seen.

This practice may have been the seed for Chillida’s long hours of observing the sea and horizon in San Sebastián and his patient attention to the music of Bach. “Bach is my master,” Chillida wrote. “He revealed to me the subtle relationships between time and space.” The affinity that Chillida felt for Bach is clear in their respective oeuvres, in which mastery of variation, sense of timelessness, capacity for synthesis and profound mysticism are all present.

The spatial concepts behind Chillida’s work connected him with thinkers and poets such as Bachelard, Heidegger, Emil Cioran and Jorge Guillén. The idea for his final project, though ultimately unfulfilled, was inspired by a realization that the work quarrymen do—extract stone—was akin to his own practice of introducing space into matter. An ambitious project of intervening within the space of a quarry to transform it into art began in Tindaya, Fuerteventura, in the Canary Islands, in 1994. Architect Lorenzo Fernández-Ordóñez, son of Jose Antonio Fernández-Ordóñez—an engineer and close collaborator of Chillida’s—describes it as “a work void of materials … a large interior space (a roughly fifty-meter cube) in the belly of the mountain.” He adds that “Chillida valued the mountain’s surroundings as something precious—an empty and essential place, just like the sculpture itself. His work presents the island with a monument that resembles the essence of the land itself: sky and earth, silence and horizon.”

Chillida felt that he was more than just a sculptor, but rather a conceptual artist. He wrote, “A concept is elastic. That is, you can establish the period of the concept’s performance not in its moment, but over a period of time, within a process. My work contains a conceptualism that’s constantly self-limiting and self-criticizing.”

Though he proclaimed his love for wrought iron through- out his life, his explorations nevertheless continued into other materials like stone, wood, alabaster, paper, felt, chamotte clay, concrete and Corten steel. Chillida’s prolific career was shaped by his spirit of inquiry and experimentation, moving forward always, as he said, with “doubt and wonder.”

–

Peio Aguirre is an editor, writer and independent curator.

Ignacio Chillida is a master engraver and a son of Eduardo Chillida. He was his father’s studio assistant.

Susana Chillida is a filmmaker, psychologist and pedagogue and a daughter of Eduardo Chillida.

Anita Feldman is the deputy director of curatorial affairs at the San Diego Museum of Art. Previously, she was head of collections and exhibitions at the Henry Moore Foundation in England.

Lorenzo Fernández-Ordóñez is a Spanish architect and teacher.

Isabelle Maeght is the general manager of the Galerie Maeght and sits on the Maeght Foundation board.

Rafael Moneo is a Spanish architect and a longtime friend and collaborator of the artist.

Joaquín Montero is a Basque architect and a collaborator on Chillida Leku.

Peter Murray is the founder and former executive director of Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Jesús Uriarte is a photographer and collaborator of the artist.

Susana Chillida’s memoir, Eduardo Chillida and Pilar Belzunce: Memories of a Daughter (2024), is now available from Hauser & Wirth Publishers.