Site

The Architect and the Artist

By Leah Singer

Le Corbusier and Nek Chand in Chandigarh

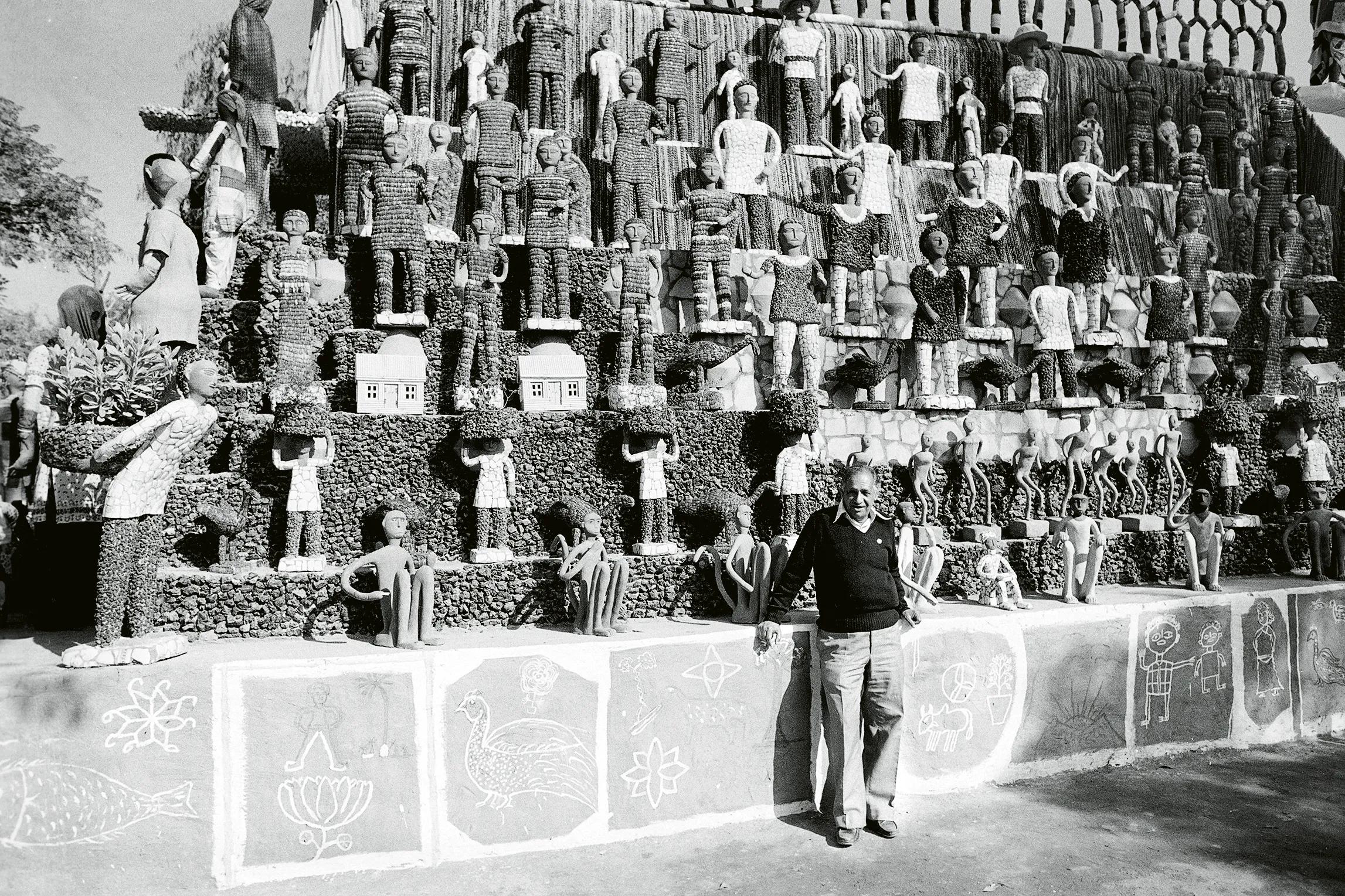

Figures in Nek Chand’s Rock Garden, Chandigarh. Photos: Anindito Mukherjee via Redux Pictures LLC

I recently traveled through Northern India across a diverse stretch from the Himalayan city of Leh to the tribal lands of Arunachal Pradesh, on to Kolkata, the triangle of Jaipur, Agra and New Delhi and finally to Chandigarh—the celebrated planned city built from the ground up in the 1950s as a symbol of the newly independent country.

Unlike much of India, with its abundance of activity and density, Chandigarh stands out in part for what it lacks. The streets are not crowded and chaotic; they look more like those of a European city, with traffic circles and wide boulevards. Bustees, or shantytowns, have been pushed to the outskirts, and it’s unlikely you’ll find a cow, a sacred Hindu animal, roaming around freely as you would elsewhere in India because they, too, live on the periphery in gaushala, or animal shelters. The bustling bazaars at the core of Indian life don’t exist here; instead, an outdoor pedestrian shopping mall with an expansive concrete plaza serves as a de facto town square. One local told me that Chandigarh is not an Indian city, possibly for these very reasons, but Chandigarh is also unlike any other city.

The lingering effects of the 1947 partition, which displaced fifteen million people and led to the deaths of as many as a million, were still present when Chandigarh’s foundation stone was laid in 1952. Against such a tumultuous backdrop, what happened next seems inconceivable: Two distinct architectural wonders emerged side by side—one by a renowned Swiss-French architect who finally realized his dream of building a city from scratch, and the other by a self-taught artist, a Hindu refugee traumatized by displacement, who transformed the urban waste of the new city into a landmark of art.

Today, Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh administration buildings—known as the Capitol Complex—are a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the nearby Rock Garden created by Nek Chand, a sixty-acre sculpture park, stands as one of India’s most popular attractions after the Taj Mahal. While Le Corbusier’s name has long been canonical, Chand’s is still not widely known outside India. And yet an origin story of Chandigarh that takes both into consideration, as complementary protagonists in the city’s creation, reveals not only the commonalities between their work but also the ways in which the city and the garden function today as mirror images of a vast urban experiment. It is believed that the two men never met.

Nek Chand. Photo: Suresh Sharma Courtesy the Estate of Nek Chand

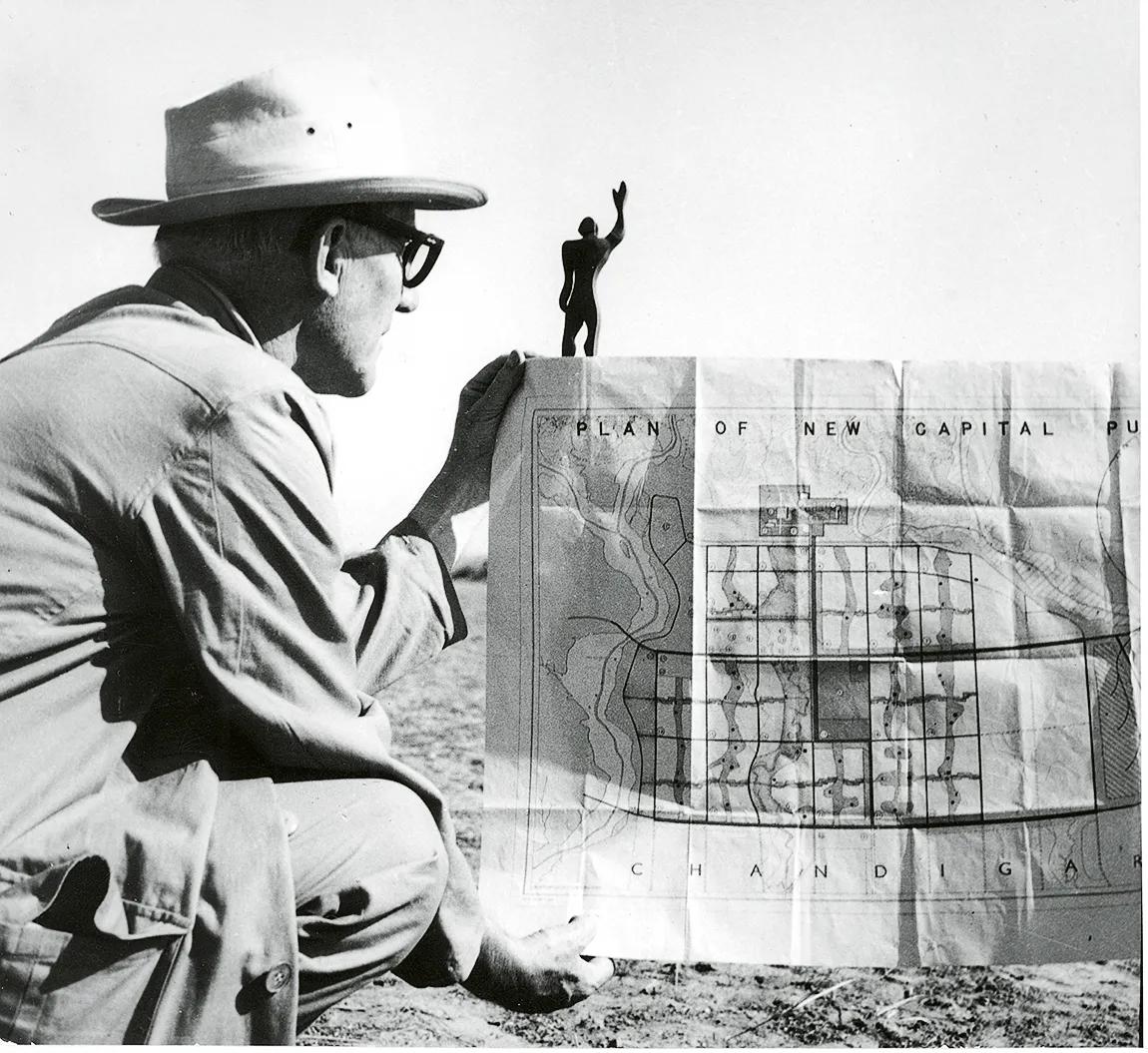

Le Corbusier. Courtesy Le Corbusier Foundation © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

The aesthetic which will emerge from this will be a new aesthetic.

Le Corbusier

—

When Le Corbusier was chosen to take over the Chandigarh master plan, originally drawn up by New York architect Albert Mayer, he was already sixty-three and widely esteemed, yet none of his many city-planning projects up to that point were ever constructed. Not wanting to jeopardize his other commissions by moving to India, he enlisted his cousin, architect Pierre Jeanneret, to be his on-site proxy. English architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, experts in tropical architecture, were also enlisted. Jeanneret traveled to India with Le Corbusier in February 1951 and soon took on the role of chief architect of the city, staying until 1965, only two years before his death. As a testament to his love of the region, he asked his niece Jacqueline to scatter his ashes in Chandigarh’s Sukhna Lake.

Le Corbusier designed much of Chandigarh from his studio on rue de Sèvres in Paris, but he took twenty-three extended trips to India before his death in 1965, visiting architectural landmarks such as the 17th century Mughal-era Red Fort, the 18th century Jantar Mantar observatory in New Delhi and, in Gujarat, the Adalaj Stepwell, an intricately carved water reserve from 1499, built five stories down into the earth. Only car trouble kept him from seeing the Taj Mahal. During these trips, he kept a notebook with him at all times, making drawings of vernacular architecture and daily Indian life, referring to it often while planning the city.

In collaboration with architect B.V. Doshi—a student who worked in the Paris studio on the Chandigarh plans and who, in 2018, became the first Indian to win the Pritzker Architecture Prize—Le Corbusier extended his reach in India to include residential and institutional buildings in the walled city of Ahmedabad. During the same years he was bringing modernist ideas to India, he completed the Chapelle Notre-Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France, in 1955—a stunning late-career example of his subversion of modernism through the use of curves and slopes, ideas he was also exploring for the Capitol Complex in Chandigarh.

Although Le Corbusier criticized Mayer’s original plan for Chandigarh as faux-modern, writing to his wife, Yvonne, that he had “crushed the American” with a new plan, he ended up incorporating much of his predecessor’s work into his own design. He took Mayer’s superblocks, multi-functional, self-sufficient neighborhood units, and transformed them into much larger sectors, assigning them numbers to delineate their location and function. His penchant for order led him to color-code the streets in each sector with a different flowering tree; the Amalta trees with cascading yellow flowers can be found in Sector 16, while pink cassia adorn Sector 27. Le Corbusier also kept the greenbelt that Mayer designed under the influence of the City Beautiful movement, which encouraged the greening of cities, calling it the Leisure Valley. Its success has given Chandigarh the reputation of being one of India’s most eco-friendly cities. The major alterations to Mayer’s plan included changing his patchwork of curvy roads into a linear grid and moving the Capitol Complex further west to higher ground. Its secluded location situated it adjacent to the place where, unbeknownst to Le Corbusier or anyone else, Chand was at work on his secret garden.

Le Corbusier’s Capitol Complex, Chandigarh. Photo: Anindito Mukherjee via Redux Pictures LLC

Every rock has a life.

Nek Chand

—

Chand was twenty-three when the partition was declared. Its impact forced his Hindu family to flee their village in western Punjab—as this was now part of Muslim-majority Pakistan—overnight and travel arduous distances to a resettlement camp across the new border. By 1952, Chand had been offered a job as a road inspector for the Public Works Department in Chandigarh.

In the dense forest near the site of his new job, Chand used empty tar drums to build an enclosure for his tools and supplies. Just beyond it, he built a private area he called “the store” to keep the thousands of rocks he collected on his walks in the nearby Shivalik Hills and along the dry seasonal rivers. He transported many of the rocks by bicycle, marking the heavier ones for later pickup in a friend’s truck. It wasn’t long before he had transformed his forest sanctuary into a fantasy land, a labor of love he kept secret for eighteen years, telling only his wife, Kamla, who soon started helping him.

Chand saw creviced human faces, strange animal shapes and abstract forms in the large rocks he collected, displaying his favorite ones like artworks on mosaic stone ledges and plinths. He believed he was creating a divine place where all of his objects would be revered like the characters in Indian mythologies and in his mother’s childhood stories about enchanted kingdoms. Every part of the garden’s construction took into consideration its function as a sacred site.“This is for all gods and goddesses of the world,” Chand said, “so I thought that people should bow and bend their heads … that is why I made the arches so low.”

The creation of Chandigarh required the demolition of about twenty villages. While clearing large sections for road construction, Chand came to see the potential in recycling the detritus left behind. He began stockpiling all manner of refuse: broken pottery and tiles, discarded glass bangles, electrical outlets, pipes, earthen pots, old bicycle frames. At the same time, he collected the castoffs of the very materials Le Corbusier was using to build the city: rebar, concrete, iron slag and bitumen, among other things. All these disparate materials would be put into service to build the Rock Garden, in much the same way that, thousands of miles to the west in Los Angeles, Simon Rodia had also built his obsessive masterpiece, the Watts Towers, from scavenged rebar, pottery, glass and other urban-industrial leavings. Chand would later establish recycling centers across Chandigarh to provide himself with an ongoing supply of materials, aware that he was also helping to relieve the city of its trash.

Nek Chand’s Rock Garden. Photo: Anindito Mukherjee via Redux Pictures LLC

Nek Chand’s Rock Garden. Photo: Suresh Sharma. Courtesy the Estate of Nek Chand

The Rock Garden was my playground.

Anuj Chand, Nek Chand’s son

—

When he moved from collecting rocks to making sculpture, Chand built a small hut on the grounds and went there after a full day at his government job, working under the cover of night with jute bags over his head and hands to protect him from the feasting mosquitoes. Chand’s son, Anuj, told me how his father was unwavering in his commitment to the garden: working through severe weather, fending off wild animals and the many snakes that made the forest their home.

Chand made the molded heads of his sculptures by pouring concrete into earthen jugs and used discarded bicycle parts to give form to the bodies. Once the metal armatures were complete, he covered them with concrete to create a kind of armor and then clad the figures with broken tiles and crockery, small rocks and, on occasion, hair that he salvaged from barbershops. These sculptures—there are thousands of them—represent ordinary people dancing and working, Hindu deities and animals, real and imagined. He arranged the figures in sections, lining them up row upon row on high-tiered terraces facing the meandering trails.

After 1965, Chand began to envision the garden on a much larger scale, constructing multiple chambers connected by narrow walking paths with high walls of stone and concrete. The fourteen chambers in the garden are reminiscent of a typical Punjab village but also bring to mind how Le Corbusier’s sectors in Chandigarh, about twenty-five in his day and fifty-six at present, come together to form the city.

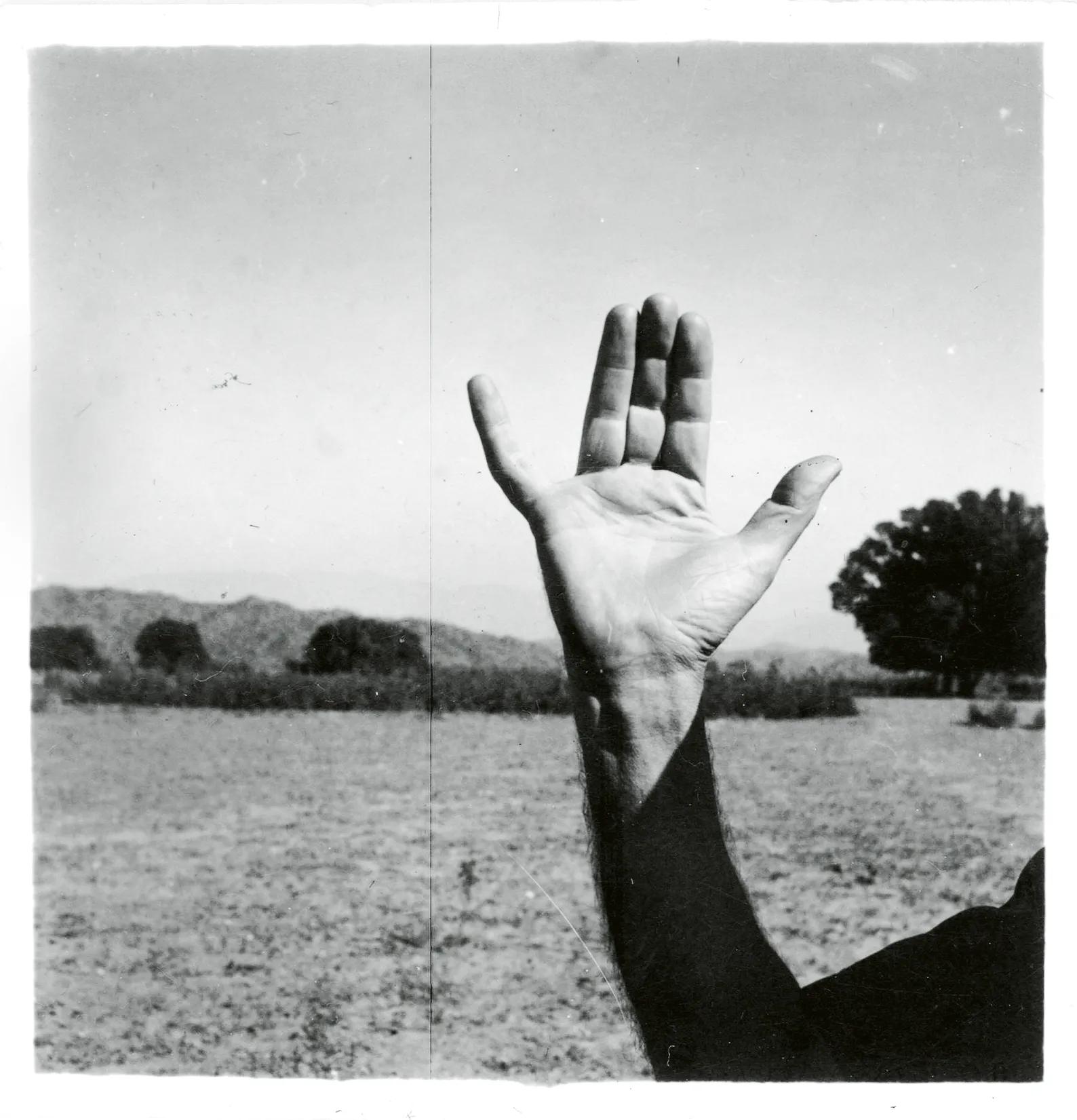

Le Corbusier’s Open Hand. Photos: Anindito Mukherjee via Redux Pictures LLC

Courtesy the Le Corbusier Foundation © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Rough concrete opens a magic door for modern architecture.

Le Corbusier

—

Chand discovered that concrete provided an effective way to mimic nature, and during the third phase of the garden in the 1990s he used the material to create masses of tangled roots and freestanding trees, like the ubiquitous Banyan trees. Le Corbusier had also, decades earlier, thought about making trees from concrete. In 1957, he wrote in his notebook that he wanted to go with Giani Rattan Singh, his architectural model maker, to “find an acceptable tree, one of those he has seen along the roadside… coat it in gypsum or mastic, to make a cast in which to pour the concrete” for a concrete tree monument for the governor’s terrace on the Secretariat.

The tree was never made, joining many other unrealized Le Corbusier projects for Chandigarh, the most disappointing loss of which was the Governor’s Palace, a building that would have completed the symmetry of the complex. But Le Corbusier’s work on the city nonetheless yielded new frontiers in his creativity. A crowning achievement of his innovations was béton brut, or rough-cast concrete. Because wood, the traditional material for casting concrete, was not available to him in India, he was forced to use sheet metal for the molds. The results were more unpredictable, leaving interesting flaws throughout the final result. He called the work the most beautiful concrete he ever made (though this view was not shared by all; Jeanneret noted that every time an important guest came to the work site, workers would touch up the concrete to mask its roughness.)

Chand watched how the béton brut process was carried out on the Capitol Complex and began using it in the Rock Garden. Rather than conventional molds, Chand used the jute bags that had contained the concrete in powdered form. He repurposed the soft bags into molds for the wet concrete, creating bulbous amorphous forms that he would stack to make weight bearing columns and walls. While Le Corbusier’s béton brut was austere, Chand’s became surrealistic.

Le Corbusier's Tower of Shadows. Photos: Anindito Mukherjee via Redux Pictures LLC

One should never see the city.

Le Corbusier

—

The Capitol Complex was designed to open onto nature on the Himalayan side and be closed like a basin on the other three sides. Le Corbusier’s intention was to isolate the complex from the city, disrupting but not fully concealing the views by using plantings and artificial hills made from the excavated earth of the construction site. He used similar conceits for a few of the monuments he designed for the Capitol, the idea being to create a feeling of serene focus.

Along with the Secretariat, the Palace of the High Court and the Palace of Assembly, Le Corbusier planned a series of monuments for the esplanade that were posthumously built after years of bureaucratic setbacks. Drew had suggested the idea of monuments, telling Le Corbusier that they would serve to reflect his personal mythology, which included an interest in the cosmos. It’s easy to imagine that the monuments were influenced at least in part by Le Corbusier’s admiration for the Jantar Mantar observatory in New Delhi, where the structures act as tools for learning while functioning as sculptures.

The Chandigarh monuments include the Tower of Shadows, a skeletal structure built to test the effects of solar behavior on brise-soleil construction; the Geometric Hill, a stylized viewing platform with a concrete mural embedded at the base that depicts the twenty-four-hour movement of the sun; the Open Hand, a metal, mudra-like sculpture that pivots with the wind, conveying peace and reconciliation as it rises eighty-five feet above the Trench of Consideration, Le Corbusier’s “people’s court,” a public forum for debate that is rarely used and built sixteen feet below ground, obscuring everything but the sky. Finally, there is the Martyrs’ Monument, a sparse memorial dedicated to the victims of the partition, which incorporates Indian symbols and a ramp leading down to a void.

Photo: Jürg Gasser / gta Archive ETH Zurich

I have faced many perils.

Nek Chand

—

In 1969, after building up the garden, Chand began to worry. The forested land he occupied was protected by government decree, which meant that he was using it illegally and was in violation of the Chandigarh Edict, drafted by Le Corbusier to protect the city from unauthorized building. He feared that if his work was discovered he would lose his job and the garden would be destroyed. Hoping to court favor with the chief architect of Punjab, M.N. Sharma, he invited him to visit the garden. Upon seeing the beauty of the project, Sharma reassured Chand. “No one could imagine the great creative mind of this humble genius who had no political or any other support,” Sharma said later. “I did not have the heart to go by the rules and advised him to continue his work in secret.”

A few years later, the garden was discovered by government workers who came upon it by chance. Dr. M. S. Randhawa, chairman of the Chandigarh Landscape Advisory, recognized the importance of the garden and passed an order ensuring that it “be preserved in its original form, free from interference of architects and town planners.” Chand stepped down from his road inspector job and was made creator-director of the garden, with a salary and a staff to help him fulfill his dream. The garden opened in 1976 and major work continued all the way up to Chand’s death on June 12, 2015.

The garden was an instant success with the public, but to others in Chandigarh it was a thorn. In 1989, Chand stood before the High Court, defending his creation in the face of eviction. The court wanted to expand its parking lot and create a road system through the garden; it accused Chand of violating the master plan. The threat never came to pass but the garden continued to face challenges. While Chand was on a trip abroad, dozens of his statues were vandalized. This act prompted John Maizels, the founder and editor of Raw Vision, a magazine committed to outsider art, to initiate the formation of the Nek Chand Foundation, to ensure the garden’s protection.

Nek Chand’s Rock Garden. Photo: Anindito Mukherjee via Redux Pictures LLC

Le Corbusier’s Capitol Complex. Photos: Anindito Mukherjee via Redux Pictures LLC

The seed of Chandigarh is well sown.

Le Corbusier

—

To this day, the garden remains hidden. There is no sign of it from the street or even from the parking lot—it exists behind a formidable wall made from concrete cast in the same tar drums Chand first used to build his storeroom and conceal his work. On the other side of the wall, the garden exists as an evocation of his lost ancestral home.

The spatial tension that Chand created in the garden’s structure—paths that wind through a series of stone ramparts, low doorways, narrow staircases and labyrinthian passages—was designed deliberately to force visitors to pay attention. This sense of control and play also lies at the heart of Le Corbusier’s concept of promenade architecturale, the walk of perception, in which an acute awareness of the architecture is revealed while moving through it.

In a region mired in post-partition unrest, a planned modern city to serve as the new capital of Punjab became a reality three quarters of a century ago. The dusty alluvial plain north of New Delhi where Chandigarh was built is an unlikely setting for such a monumental accomplishment, but equally striking is how Le Corbusier and Nek Chand could both triumph there as perfect foils.

—

Leah Singer is an artist and writer based in New York.