Essays

“That’s How You Live”

Remembering Juanita McNeely (1936–2023)

By Hall W. Rockefeller

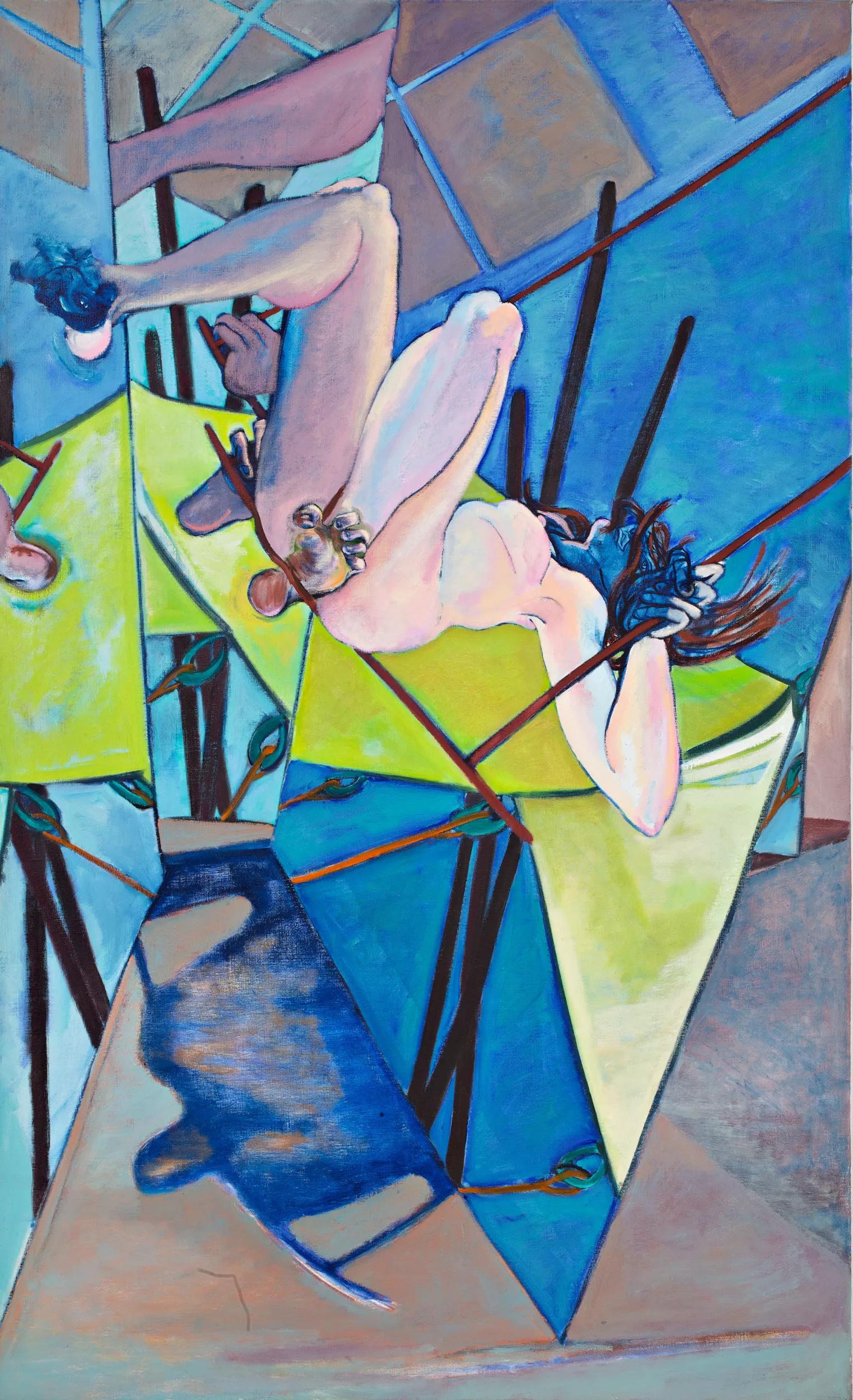

Juanita McNeely, Triskaidepatych, 1986, panel twelve. Oil on linen, 72 x 36 in. (6 x 3 ft.). Thirteen panels, overall: 72 x 624 in. (6 x 52 ft.). Courtesy James Fuentes Gallery LLC

My relationship with the painter Juanita McNeely, who died in October 2023, began with one remarkable work. Weeks before pandemic lockdowns began in the United States, I had wandered into the James Fuentes gallery on Delancey Street on one of my monthly trips to the Lower East Side in search of women artists; at the time, I was conducting interviews for my project “Less Than Half,” which has evolved into a series of courses focused on teaching women to collect the work of women artists. Inside the gallery, I found myself immersed in a continuous painting in thirteen parts, lining two perpendicular walls of the room—McNeely’s Triskaidepatych (1986).

Juanita McNeely, Triskaidepatych, 1986, panel thirteen. Oil on linen, 72 x 36 in. (6 x 3 ft.). Courtesy James Fuentes Gallery LLC

Juanita McNeely, Triskaidepatych, 1986, panel three. Oil on linen, 72 x 36 in. (6 x 3 ft.). Courtesy James Fuentes Gallery LLC

A series of bodies in paint, the work seemed electrified with life. As McNeely would tell me when we met a few weeks later, anatomical correctness was never her concern when she painted the body. These were images drawn not from models but from everyday observation. If they didn’t look right, they felt right.

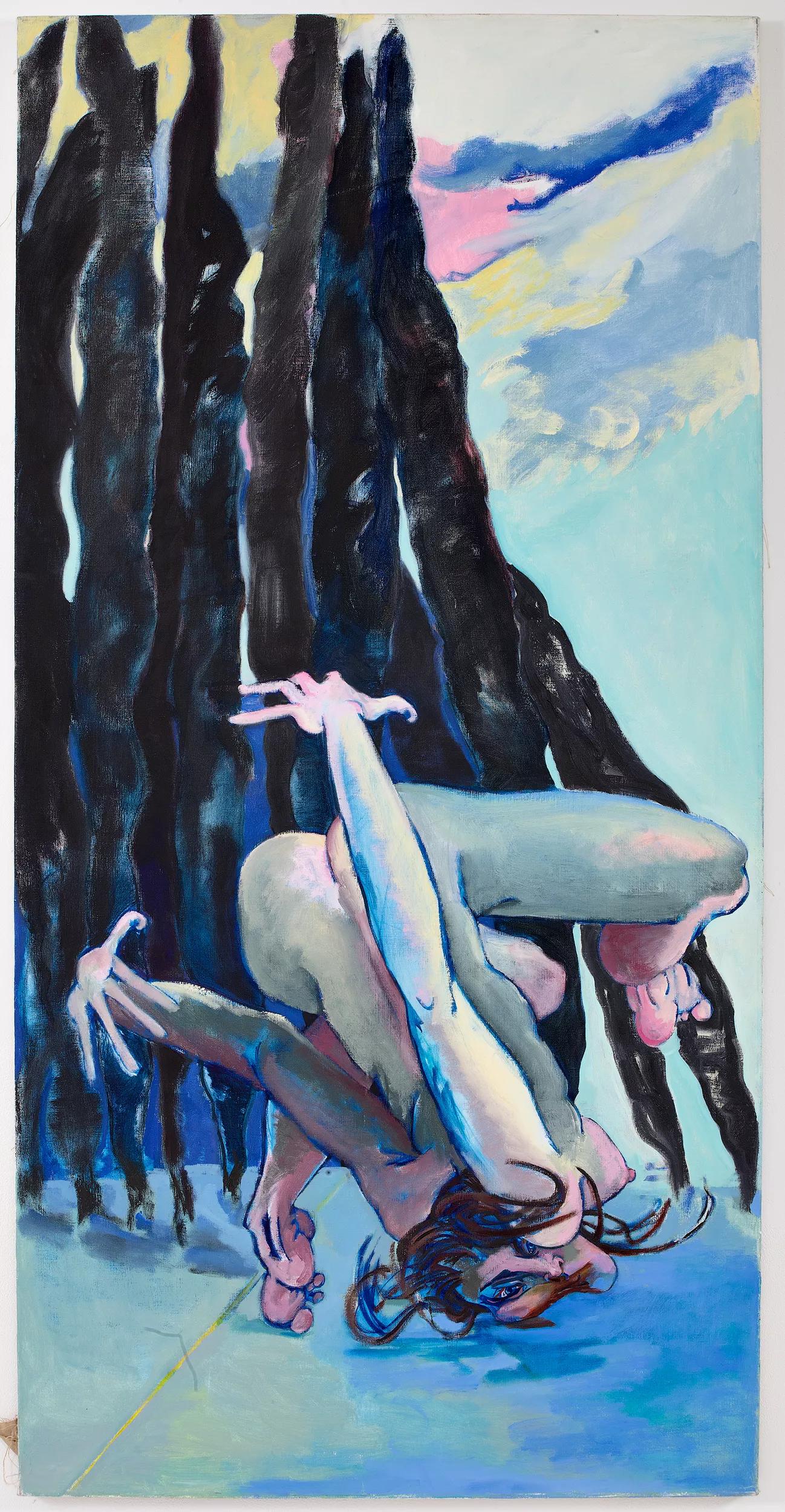

The bodies in Triskaidepatych are often incomplete, or upside-down—some positioned with the almost absurd vertiginousness of a Tintoretto. They are foreshortened, armless, legless, dissolving into backgrounds of blue or pink, obscured by brushy lines or refracted in a mirror. (The idea of McNeely painting a staid seated portrait is almost comical.)

In one frame of the painting, a horse—that symbol of artistic achievement in faithful rendering—is not much more than a pink oval, a body secondary to its legs, which are akimbo, its hooves perched on stilts, threatening to give out beneath the animal’s awkward weight.

Nearby is an image of Bacon-like grotesqueness, a foot caught in a rope or chain, the body attached to it upended, exposing a mass of innards and bones, a ribcage spilling carnage. Another panel shows a crouching woman, her face thrust towards the ground and her arms flung straight back in a pose not even the double-jointed could achieve.

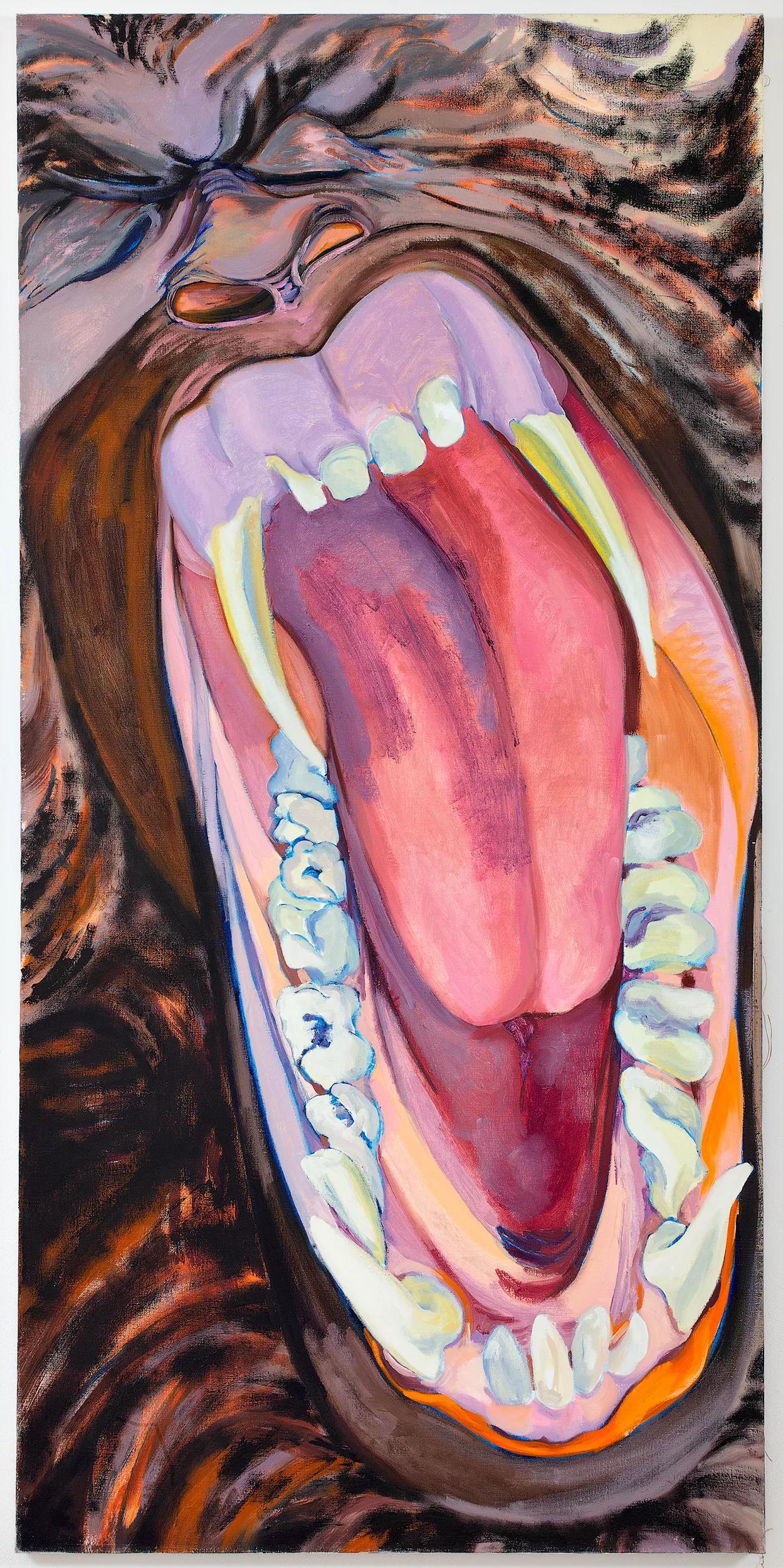

From one panel to the next, portraits of acute psychological distress and relentless physical pain spool out. I think of theseworks less as a story—agony and anxiety lack narrative—and more as a run-on sentence, clauses tumbling over themselves with energy and emotion. The work’s final panel—filled with the screaming face of a primate, teeth bared, eyes squeezed shut—functions as a kind of exclamation point.

I learned later that McNeely began this work just after she started using a wheelchair, informed by her doctors that she wouldn’t be able to paint on a large scale again because of a spine injury. That the work was in thirteen parts seemed appropriate—a number large enough to make a point and to say something about bad luck: It wasn’t going to stop her.

I didn’t know any of this then, but I could sense McNeely’s spirit in the work. I also knew nothing of her biography: her upbringing in St. Louis, where she studied the work of Max Beckmann (an influence more obvious in her early work); the cancer she suffered as a young woman; the harrowing abortion she underwent. I knew only that I wanted to know more, and I immediately asked the gallery if I could speak to McNeely in person.

“For years they were saying, ‘Painting is dead,’” she recalled—to which she responded: “Blah blah blah.”

Westbeth Artists Housing, founded in 1970 as affordable housing for artists and their families, is a 383-unit apartment building and arts complex. Far less eccentric and infamous than the Chelsea Hotel, it has served as one of the city’s sturdy refuges for creativity, home to figures like Hannah Wilke, Diane Arbus, Merce Cunningham and Hans Haacke. I always feel a thrill when I visit an artist there—its check-in desk, elevators and windowless hallways, utilitarian and without frills, bely the lives and the work behind each door.

McNeely spent decades of her life painting at Westbeth, and it was there that I met her in February 2020.

As with so many artists’ living spaces, hers was the antithesis of a gallery, its cluttered fullness neither studied nor unkempt. Paintings hung on the walls, of course, but there were also vases and jars scattered on top of bookshelves and sideboards, the vessels covered with contorted figures as if her subjects had found a new home on the surface of domestic objects, art leaching into life.

I asked her about the ceramics, wondering how they had come into her work. “Create a perfect pot,” she recalled a teacher ordering when she was a student at Washington University in St. Louis. Knowing there was no such thing, she deliberately dropped hers, shattering it. Her husband, Jeremy Lebensohn, handed me a vase to look at, and I worried I would do the same without meaning to.

Over the next couple hours, McNeely told me stories about coming into her own as an artist and about her restless beginnings. In art school, when she grew bored with painting the same models over and over again, she asked to take a semester off in order to return with work that would convince her teacher to let her paint what she wanted—and it worked.

Her choice of medium was also unusual at a time when the definitions of art were expanding to include conceptual work, performance, land art, happenings and video; pretty much anything that wasn’t traditional was on the rise, and painting in particular had become a backwater. “For years they were saying, ‘Painting is dead,’” she recalled—to which she responded: “Blah blah blah.” Fellow feminist artists had found a new tool for art by using their own bodies, partly as a protest against sexual violence. Of painting, they reasoned: Why remain with a medium dominated by men for centuries when women could explore and claim new frontiers? But McNeely stubbornly sought to make painting over for herself.

As a member of groups like Women Artists in Revolution and the Redstockings of the Women’s Liberation Movement, she was included in important feminist shows and counted many of the participants—Wilke, Louise Bourgeois, Joan Semmel and Alice Neel—as friends and acquaintances. But her forays into feminist-centered work like ceramics was shaped by a different ethos than that of colleagues who were experimenting with craft, like Judy Chicago, whose ceramic plates were fashioned into vulvas in The Dinner Party, or Miriam Schapiro, whose Pattern and Decoration movement was unflinchingly feminine. For McNeely, painting on a vessel simply seemed like an analog to her multi-paneled canvases; following the figure as it dances around the outside of the pot is as episodic as moving your eyes across a triptych. Ceramics solved a formal problem for her, not a political one. “If you’re using the figure,” she told me, “it’s easy to keep going someplace.”

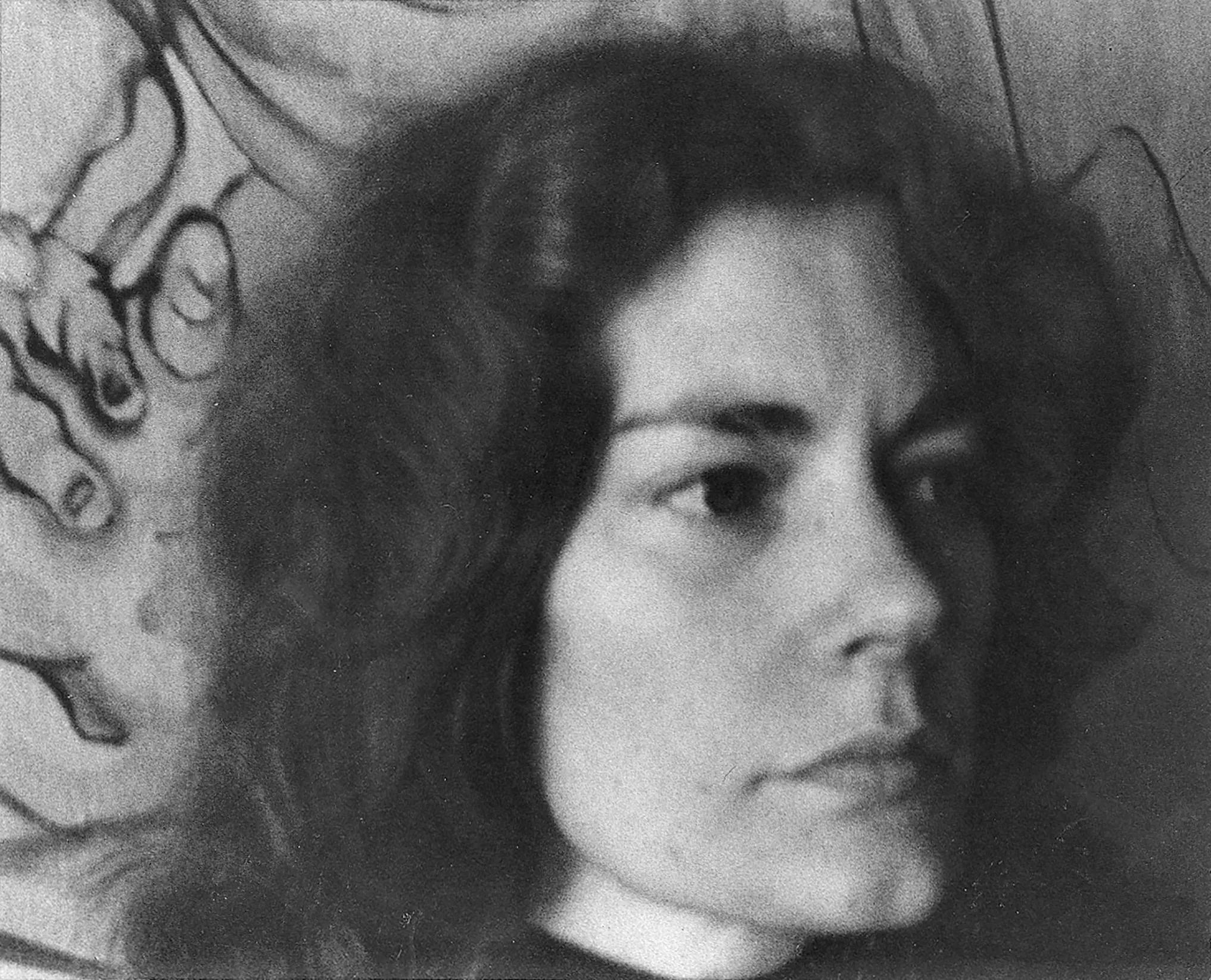

Juanita McNeely in front of one of her paintings, 1977. Courtesy Jeremy Lebensohn

From left: Juanita McNeely, Alice Neel, Lucia Vernarelli and Diana Kurz at an Alliance of Figurative Artists meeting, 1971. Courtesy Marjorie Kramer

When a mother complained that the work in one of McNeely’s exhibitions wasn’t appropriate for her young daughter, McNeely told me that she countered immediately: “What is so awful about a woman bleeding? That’s how you give birth. That’s how you die. That’s how you live.”

McNeely’s story is full of bodily pain—she struggled with hemorrhaging as a young woman and early bouts with cancer forced her to have an illegal abortion in 1967. Years later, an unlucky fall left her wheelchair bound. She told me, also, of an attempted rape at the hands of a gallery visitor. For her unflinching honesty about these subjects I remain grateful.

As an interviewer, you can rarely give to your subjects what they’ve given to you; mostly, you express gratitude and hope you asked good questions. At the very least, your responsibility is to safeguard the stories you’ve been given—and in McNeely’s case, as it would happen, I dropped the metaphorical vase. Soon after I left Westbeth, the pandemic set in and we retreated to our homes. Somewhere in the chaos, I had to reset my phone’s memory, and in the process I lost the recording of our interview.

I knew McNeely was frail and her memory already fuzzy with age. I knew, too, that she hadn’t participated much in the way of recorded interviews before I spoke with her. I worried that I had lost a piece of history. Was there another recording of her voice out there like this? Had I sacrificed her time and her trust and her candor to the ether? I consoled myself by insisting I could rerecord the interview, but when would this pandemic be over? And when it was, would McNeely—in body or mind—be there when I could come back to Westbeth?

Thankfully, in 2022, I arranged another interview. When I did see her again, even the short time was visible in her face, significantly less full than it had been two years before. My heart sank thinking of the lost recording, assuming I would not hear the same anecdotes and honesty. But if her delivery was a little slower, the snap of a comeback and punch line were all still there. (The transcription of our talk was published in 2022 by James Fuentes Press.)

Today, one of the most prominent records of McNeely’s life is Is It Real? Yes, It Is!, a 1969 painting depicting the illegal abortion she underwent two years earlier, a searing work that was acquired by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 2022. It now hangs in the museum’s permanent collection galleries, its wall label referencing the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs decision that reversed fifty years of federal protection of abortion rights. The work was the first image of an abortion to enter the museum’s collection.

In Google Image results for the painting, the image is blurred, warning the browser of “explicit content.” I am sure McNeely would be disappointed knowing this, as she emphatically insisted that life be looked at straight in the face. When a mother complained that the work in one of McNeely’s exhibitions wasn’t appropriate for her young daughter, McNeely told me that she countered immediately: “What is so awful about a woman bleeding? That’s how you give birth. That’s how you die. That’s how you live.”

The monumental painting at the Whitney is fractured into nine vignettes, snapshots of a harrowing experience. It was in a similar manner that I came to know McNeely, her long life revealed to me in small but vivid flashes. Like her other paintings, the panels represent exploration, nonconformism, rebellion, torment and pain—embodying a life lived in full.

–

Hall W. Rockefeller is a writer and speaker specializing in the work of women identifying artists. She is the founder of Less Than Half, an online education and advisory platform dedicated to raising the profile of women artists.