Portfolio

Some Notes On Soaring

Ekow Eshun on the work of Christina Kimeze

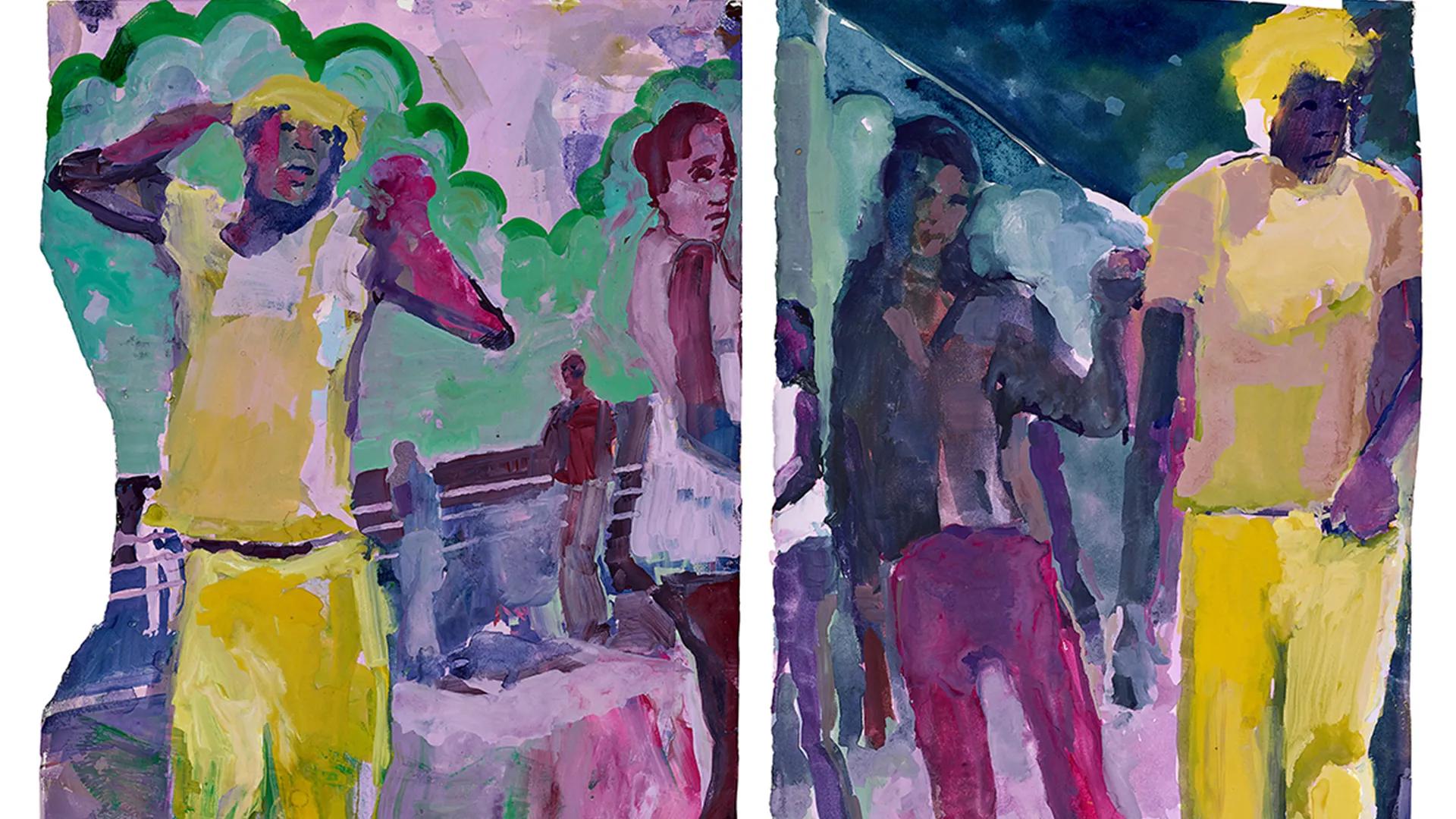

Christina Kimeze, Get Rollin (1) and Get Rollin (111) (detail), 2024. Photo: Matthew Hollow

Christina Kimeze’s Soaring III (2024) depicts two female figures moving through a realm rich in flora. Kimeze’s family belong to the Baganda people of Uganda, and we recognize the rich plant life of that country in the painting. The setting is dense with matoke, a broad-leaved banana plant ubiquitous in Uganda. Kimeze renders her women in the same shades of teal, sage, citrine and juniper as the foliage around them, conjuring them as denizens of a landscape abundant and mysterious with life—from the creatures that rustle through the undergrowth to the flowers that unfurl their petals with a faint sigh at the first light of day.

In the creation myth of the Baganda, the first person on Earth was named Kintu. One of his first acts was to plant a matoke tree, which thrived in the East African soil and became a staple of nourishment for his descendants. The belief held by the Baganda in their exceptionalism, as the first peoples of Uganda, was exploited by the British under colonial rule in the 19th century. Used as “agents of imperialism” by Britain, according to the scholar Colette Armitage, the Baganda invaded and annexed their regional neighbors. On whichever territory they conquered, they planted matoke trees as a means of asserting their dominance over the land. Victorian-era British presence stoked ethnic and regional tensions that continue to reverberate through the present day in Uganda. It also helped build a colonial imaginary of Africa and its peoples as irredeemably uncivilized. This was the view of Africans that Joseph Conrad described in Heart of Darkness, casting them as “rudimentary souls” who “howled and leaped and spun and made horrid faces” from deep in the tropical mire.

With that legacy of conquest and misrepresentation in mind, Kimeze’s nature-suffused paintings can be read as acts of reclamation. Maybe the woman who stands with arms raised in a glade of purple- and orange-leaved matoke trees in Soaring (1) (2024) illustrates the form a Black relationship with nature might take when it is not predicated on legacies of colonial power, but instead on kinship and connection and a belief in the worth and wonder of people and place. So that to walk on the land is to walk with the land. It is to raise your hands up into a canopy of purple and orange leaves and feel a kind of soaring as you do.

This is perhaps what Édouard Glissant had in mind when he spoke of tremblement, or “trembling thinking,” a rejection of ideologies of terror, domination and “all categories of fixed and imperial thought” as a precursor to establishing “real contact with the world and with the peoples of the world.”

Kimeze’s Soaring paintings also prompt thoughts of a scene in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, when the preacher Baby Suggs gathers the local Black community together in the Clearing, a “wide-open space cut deep in the woods.” Baby Suggs explains that the difference between liberation and subjugation lies in how one carries and cares for oneself in a world governed by white hostility to Black people. In the small but sovereign space of the Clearing, untroubled by white presence, the community members are free to love themselves and to draw upon that love as the basis for life ongoing. “ ‘Here,’ she said, ‘in this here place, we flesh; flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass. Love it. Love it hard.’ ”

I am reminded, too, of standing on the Atlantic coast of Ghana one afternoon a few months ago. I watched a bird soar upward and then hover motionless in the air, scanning the water below for the telltale ripple of a fish. I thought: How does it stay aloft? It has to do with hollow bones, yes. And with the tapered shape of its feathers. But maybe also because a bird takes flight presuming the air will hold it up. And nobody has told it otherwise.

Christina Kimeze, Arches, 2024. Oil, pastel and oil stick on suede matboard, 40 1/8 x 31 7/8 in. Photo: Matthew Hollow

Christina Kimeze, Screen (1), 2024. Oil, pastel and oil stick on suede matboard, 40 1/8 x 31 7/8 in. Photo: Matthew Hollow

Christina Kimeze, Soaring (1), 2024. Oil, pastel and oil stick on suede matboard, 80 3/8 x 63 3/4 in. Photo: Matthew Hollow

Soaring (111), 2024. Oil, pastel and oil stick on suede matboard, 80 3/8 x 63 3/4 in. Photo: Matthew Hollow

Christina Kimeze, Chase, 2024. Oil, acrylic, pastel and oil stick on suede matboard, 80 3/8 x 63 3/4 in. Photo: Matthew Hollow

Christina Kimeze, Soaring (11), 2024. Oil, pastel and oil stick on suede matboard, 80 3/8 x 63 3/4 in. Photo: Matthew Hollow

–

Ekow Eshun is an author and curator. His exhibition “The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure,” is on view at the North Carolina Museum of Art through June 29, 2025. His book The Strangers: Five Extraordinary Black Men and the Worlds That Made Them will be published in the United States in July.

Christina Kimeze lives and works in London. She uses texture and luminosity to explore themes of interiority, belonging and home. Her work is currently the subject of a solo exhibition at South London Gallery and included in “Women & Freud: Patients, Pioneers, Artists” at the Freud Museum in London.

“Christina Kimeze: Between Wood and Wheel” is on view at South London Gallery through May 11, 2025.