Conversations

At Work in the Garden

Uman in conversation with Matthew Higgs and Annatina Miescher about displacement, community and letting art speak for itself

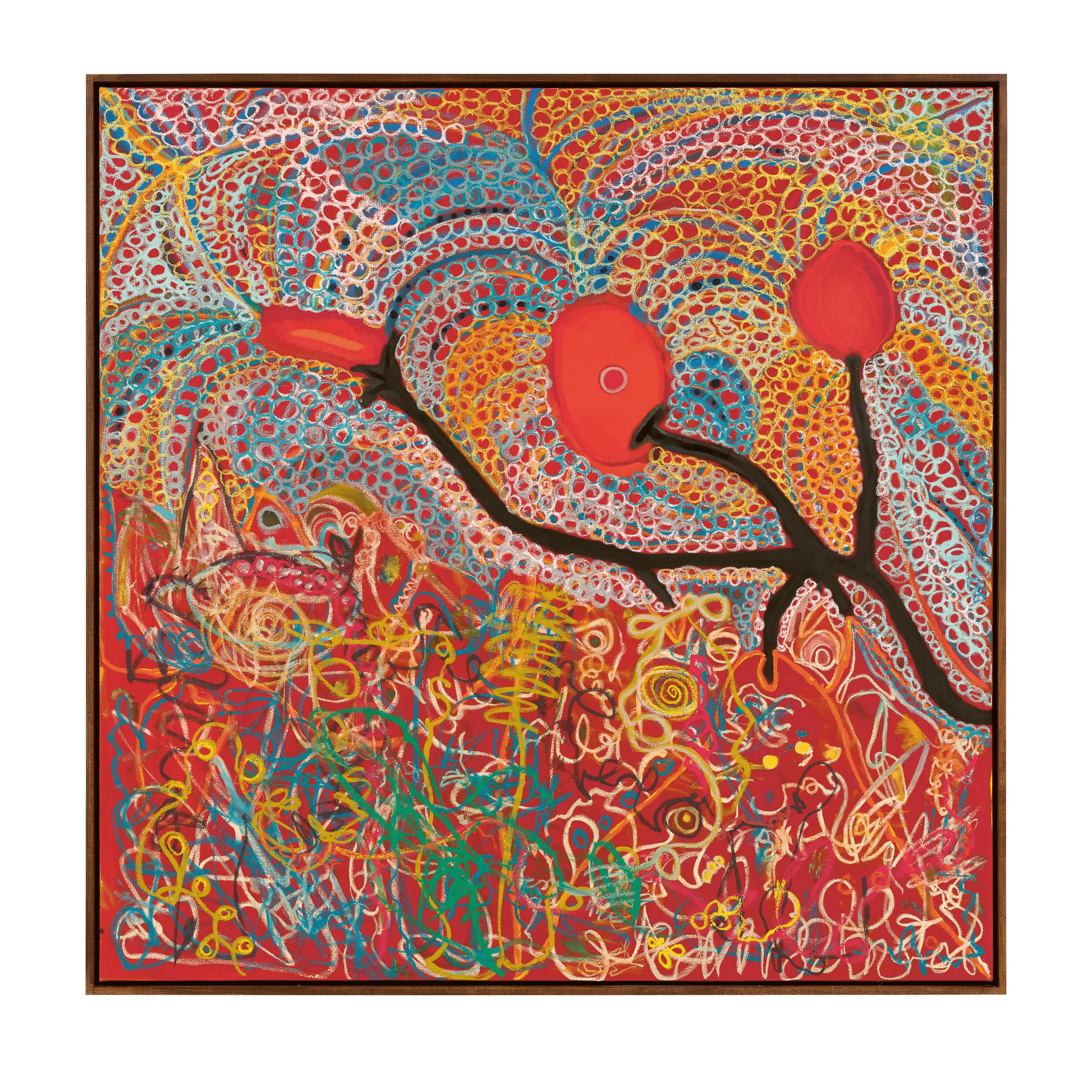

Uman, Untitled, 2022. Acrylic, oil and oil stick on canvas, 62 1/2 x 62 7/8 in. © Uman. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Nicola Vassell Gallery

Matthew Higgs: It’s a pleasure to be back in the studio in Albany with you and have this conversation. I thought we could begin in a kind of straightforward place, but also a quite complex one, which is your early life and the transition into living in New York, starting in the early 2000s.

Uman: Well, I grew up in Kenya and Somalia. My parents wanted me to learn English, but there was no English-speaking school in Somalia. A large part of our family lived in Kenya. Early on, I was making things, mostly clothes, and I doodled and drew a lot, which my family was not a hundred percent supportive of. Education was very important for them. They wanted us to succeed beyond where they were.

Higgs: So you’re ten or twelve years old, and next you find yourself no longer living in your home country, having to leave because of the civil war. You’re living adjacently, in Kenya.

Uman: Which I felt was my home, too.

Higgs: So in some respects they were the same.

Uman: They were the same. As a child, you didn’t think about it. It didn’t affect me as it affected the adults in my family, who didn’t speak Swahili or English. The war just felt like, “Okay, now things are different. Not everybody has a home.” We had people camping in our house, and it was really a terrible time for them. But I thought it was fun, because I didn’t have to go to school. There was this whole interrupted period.

Higgs: But clearly for your parents and aunts and uncles, it was a significant, traumatic scenario.

Uman: They lost everything. A lot of people lost everything. You had to start from scratch, like a foreigner in the country. Even I felt like a foreigner. You would get asked for identification, even as a kid. And there were always police rounding people up, similar to how Americans treat the people who come here illegally. The refugee camp still exists to this day, thirty years later.

Higgs: And the displaced Somali people living in Kenya are still not fully embraced or absorbed into the culture?

Uman: Somehow.

Higgs: As a young person, with this shift from Somalia to Kenya, do you have any memories of your relationship with creativity changing as well?

Uman: I remember having a little film camera and thinking it was the best thing ever.

Higgs: Do you remember what you took pictures of?

Uman: A vase or a table or a car, odd things on the street. Once, my mom went to pick up the photos from the development place, and she said, “What are these? These are not pictures.” She thought it was a waste of money. I didn’t think that. I thought they were interesting.

Uman, Untitled, 2022. Acrylic, oil and oil stick on canvas, 62 1/2 x 62 7/8 in. © Uman. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Nicola Vassell Gallery

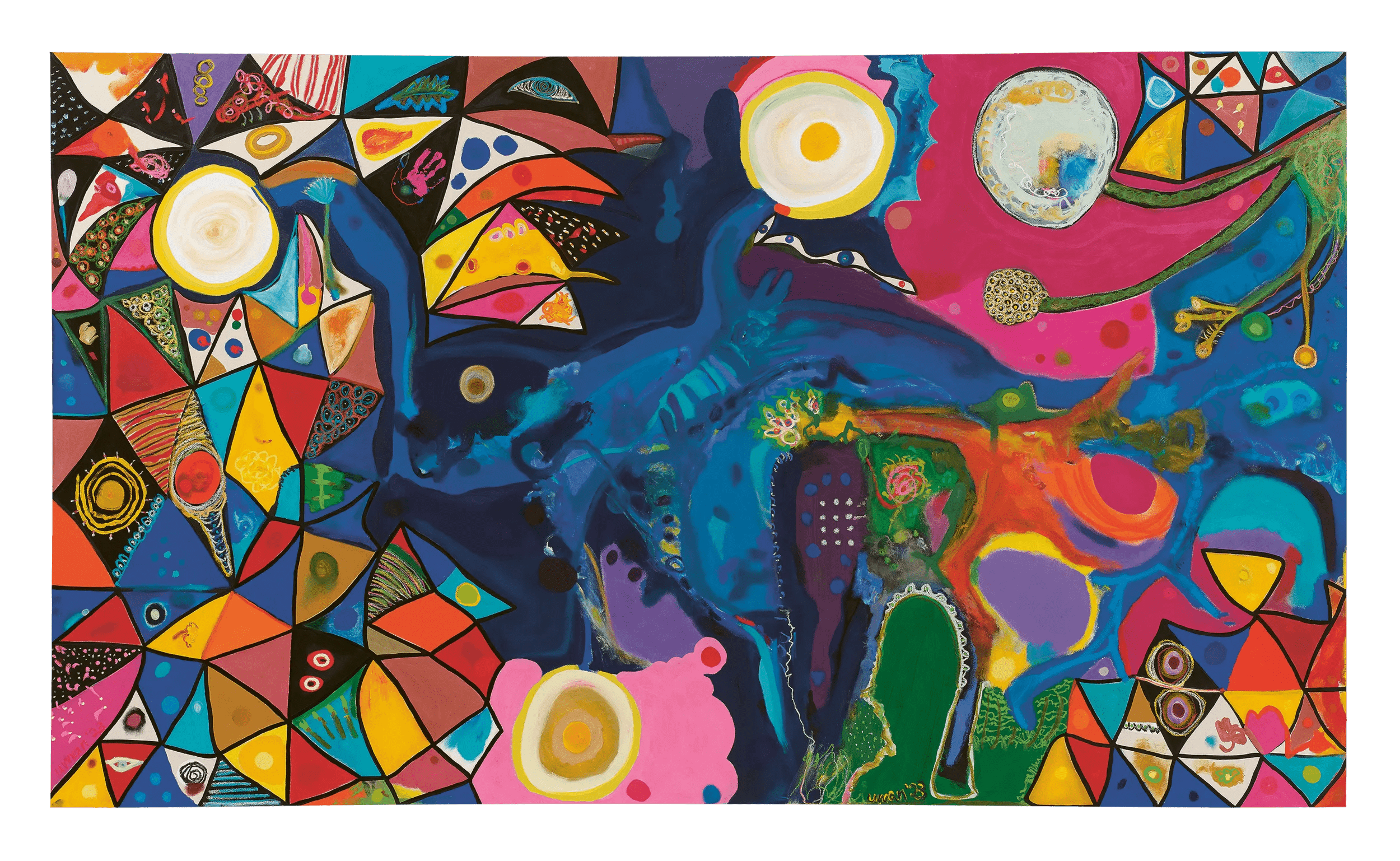

Uman, From Birth, 2023. Acrylic, oil and oil stick on canvas, 83 3/4 x 143 3/4 in. Photo: Sarah Muehlbauer. © Uman. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Nicola Vassell Gallery

Higgs: You then moved to Denmark in the early 1990s. I can’t imagine a starker change, between Kenya and Denmark, especially for a 13-year-old.

Uman: It didn’t feel very different. You have this thought of the West as a kid, that it’s like the movies. And then you find that you are living among the same types of people that you lived among before. You live in the same neighborhood with the same immigrants, as though you’re still stuck in the past.

Higgs: There’s a quote I read in an interview you did with Chris Martin, where you said that you were excited to be in Scandinavia and in Europe because it was “one step closer to the United States.”

Uman: I watched Coming to America, the Eddie Murphy movie, and I was like: “New York looks crazy! I’d love to go to New York!” I was such a dreamer. I wanted to be in New York, in Paris. I wanted to do these things and just be part of this creative, thriving world.

Higgs: So at that time in your early adolescence, you were already starting to think about the idea of yourself as a creative individual who might find a creative community and contribute and participate in ways unknown?

Uman: In ways unknown, yes. But I would say the freedom to be myself was very important. I wanted to be around people who were like me, to feel that I wasn’t judged or stuck in a community. I wasn’t particularly religious, even though I grew up very indoctrinated in religion. I didn’t feel like I believed in anything.

“I would pick up things on the streets to paint on. I never bought canvases. I worked everywhere, even when I was sleeping in Union Square.”—Uman

Higgs: There’s a quote from another conversation with you, in which you said, “I’ve always been trans. I always knew that was a part of me.” I can’t image how complicated that must have been Somali and Kenyan culture.

Uman: It was complicated. People could tell that I was different. I needed to leave Kenya because my parents didn’t know how to protect me, and they felt that the best thing for me was to move to Europe. I was in a society where I could get killed or beaten to death. It happened a few times that I was attacked by kids. My mom didn’t want me to leave, but it was something that my parents had to concede.

Higgs: I think you mentioned somewhere that you had a one-way ticket, which suggests not coming back.

Uman: I was never coming back. I thought, “I’m going to be a painter. I’m going to go to New York and do this.” It’s the only thing that made sense to me. I didn’t imagine being homeless. I never even knew what that was, living in Scandinavia.

Higgs: Where there’s a social safety net.

Uman: Yeah. New York taught me a lot of things.

Higgs: What was New York life for you when you arrived?

Uman: I was actually happy to have nothing. There was such freedom in having nothing to lose. I didn’t know anybody, but I made friends everywhere I went. I didn’t have money, but I could go into any bar and people would buy me drinks. It was just one of those places where I felt free. I think a year after is when depression started to hit me.

Higgs: What brought that about?

Uman: Poverty. Plus the fact that I didn’t have papers, and I couldn’t go back. It was complicated. I got jobs washing dishes and things like that, coffee shops that paid me under the table.

Higgs: And during this early period in New York, between a sort of euphoria of arriving and then the reality of the city, let’s say, were you able to keep making work?

Uman: I would pick up things on the streets to paint on. I never bought canvases. I worked everywhere, even when I was sleeping in Union Square. I met a few struggling artists, other people who sold things on the streets. I never really met a real professional artist until I met Annatina, in 2005.

Uman, Sumac Tree in Roseboom, 2022–23. Acrylic, oil and oil stick on canvas in artist’s frame. 86 11/16 x 86 5/8 in. Photo: Lance Brewer. © Uman. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Nicola Vassell Gallery

Uman, Matthew Higgs Planted Some Seeds, 2022. Acrylic, oil, and oil stick on cotton canvas in with poplar artist painted frame, 74 1/2 x 74 1/2 in. Photo: Adam Reich. © Uman. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Nicola Vassell Gallery

Higgs: So you meet Annatina within a year, at the beginning of this sort of downward spiral of depression?

Uman: Right. And I needed therapy, and Annatina had her clinic, which had classes and fed you, and it was free if you had Medicare or Medicaid. I went there and met her, and she asked me if I wanted to volunteer on the weekends at the garden. I started that same week, which was such a great structure for me.

Dr. Annatina Miescher: In the garden, there were all these benches with bald spots in front of them, and it looked sad. They had changed the partitions in the hospital bathrooms from marble to some disgusting thing that they thought was more hygienic. So the masons had given me these bins full of broken pieces of marble, and I wanted to make islands of that. So I was on all fours, preparing the ground, and I showed Uman the bins of marble—there was pink, white and black to choose from. And she just got into this zone, going to the bins and putting the pieces down as if she knew exactly what she was doing. It was like she was possessed. She did one island and the next and the next, and then we were done. And I said, “Uman, look. You just wrote your life story.” And she was like, “What?” There was this beautiful black turtle walking towards the next island, and that was her. She walked slowly, but steadily. Next was a black sun. Next was her whole family: her mom as a big camel and her dad as a smaller giraffe, creating a frame under which Uman stood, with her boyfriend, who was installing solar panels. Uman was a little stunned afterward, and so was I. It was amazing. Beautiful, too. Then she stood up and saw the biggest space in the garden and said, “Next weekend I’ll do something there.” I was like, “Who are you? You’re choosing the most important, central place, and it’s not your garden.” And I thought to myself, “This is a person with an extraordinary talent who, when she’s in the creative mode, is totally herself. There’s no hierarchy, no self-consciousness. Only her creating.

Higgs: Are those early interventions by Uman still there?

Miescher: I think so, yeah. The Bellevue Sobriety Garden is on the map of New York City now.

“I thought to myself, ‘This is a person with an extraordinary talent who, when she’s in the creative mode, is totally herself. There’s no hierarchy, no self-consciousness. Only her creating.’”—Annatina Miescher

Higgs: How, in your mind, did the work that you were doing with Uman sit within your idea of therapy?

Miescher: We all have different languages. In my clinic, there were lot of men with rough histories, and certainly the last thing they want to do is what the art therapist says, something like: “Today we’re going to paint feelings.” These guys would rather throw up than do that. In the clinic there was the garden and many avenues to reach people and find the seeds that would let them grow. Some were running groups, others were preparing meals. It was like a little village.

Higgs: Uman, what effect did the clinic’s approach have on your depression at the time, and the idea of yourself as an artist?

Uman: It had a big impact. This idea that you could start and finish something, and then it’s physically there, in front of you. I learned a lot about discipline. I didn’t have that before.

Miescher: Right, the discipline to stay in that zone. And also, you were safe with me, in the garden.

Uman: I was safe. I had a community. I had a sense of belonging. I had one or two people in New York who I felt safe with. And Annatina was one of those people, in that setting, that environment.

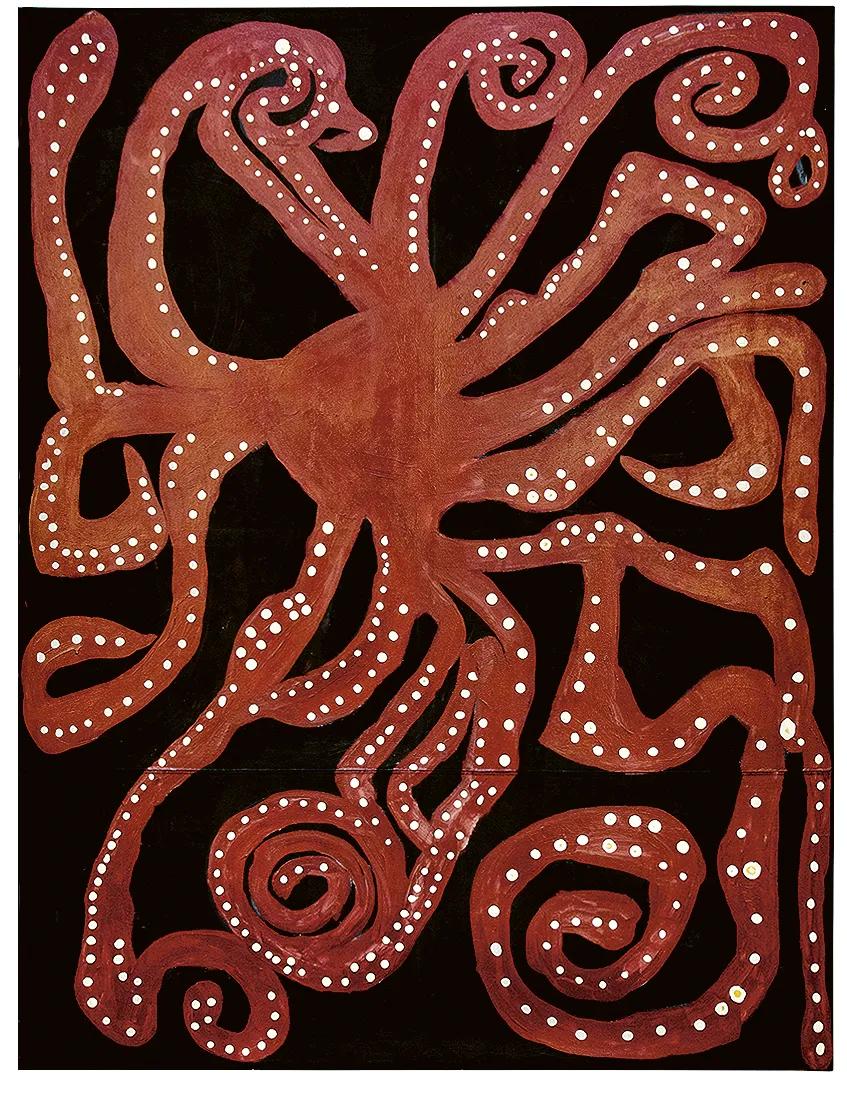

Uman, Octopus #1, 2019–20. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 96 x 74 in. (Has since been painted over by the artist). © Uman. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Nicola Vassell Gallery

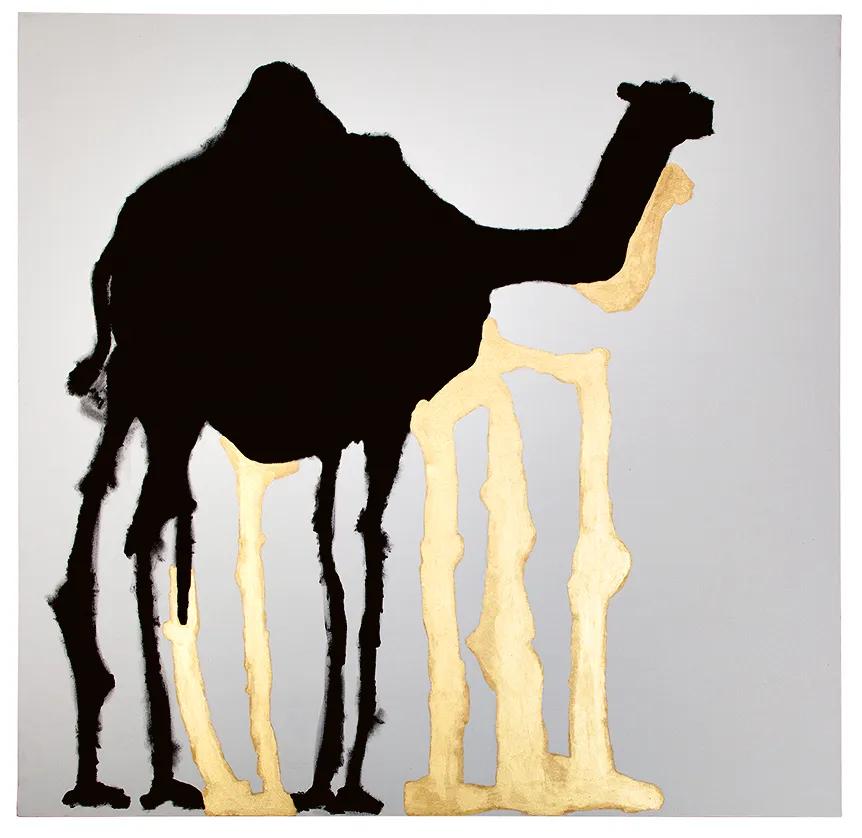

Uman, Camel #4, 2019. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 84 x 84 in. © Uman. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Nicola Vassell Gallery

Higgs: How long did the two of you work together at Bellevue?

Miescher: It wasn’t very long. Uman disappeared from my radar for years. Looking for a community and identity was also very important to her.

Higgs: When did you reconnect with her?

Miescher: It was 2012. I was no longer working in Bellevue, and by chance somebody sent me a patient named Bjarne Melgaard. He couldn’t pay, but the person who sent him said: “You might be interested because he’s an artist.” And it was love at first sight. Bjarne has a lot of troubles, but he is a beautiful person. He told me that he wanted to collaborate with crazy people. I said, “Bjarne, maybe ‘crazy’ is not the appropriate word, but I do have a lot of creative people.” He had a twenty-five-thousand square-foot studio, and I would bring people there so they could collaborate, and I wanted to bring Uman there but I couldn’t find her. It had been a long time since I’d seen her, 2005 to 2012. So I went to people in the trans community in New York, and I asked them if they would let me know where she was. And they were like, “Hell no.” So I gave them a piece of paper with my number and said, “Well, if you see her, please just give her this piece of paper.” That was in December. Uman finally called me the next April, and then she started coming up to stay with me upstate, which was a great thing.

Uman: I would take the bus and stay over the weekend.

Miescher: Bjarne, in his studio in Bushwick, had prepared a limitless amount of canvas and paint, and Uman would paint big, beautiful paintings there. That lasted nine months, working at Bjarne’s place.

Higgs: Uman, you’ve said one of the things you took from that experience of working alongside Bjarne was the idea of freedom, that an artist could do anything. I’m assuming that was quite a liberating moment for you and for your work, which seemed to grow in—is confidence the right word? Or ambition?

Miescher: I would say clarity, too.

Uman: Something I really got from Bjarne was the energy of somebody who did what he wanted and didn’t care, who didn’t feel self-conscious about things that I felt scared of—of being explicit, raw, honest. It was a very important period for me because I came away from it feeling that I could be wild on the canvas.

“There was a part of me that was so free at one point. Now, even just being on social media, I’m like: ‘Oh, I can’t share certain things about my life or what I’m working on.’ Of course, I always wanted to be a successful, well-known person, but it’s very different when it comes to the work.”—Uman

Higgs: Annatina, did you feel a responsibility in trying to keep an idea of a group together, the group of artists who came into your orbit through Bellevue?

Miescher: It was a dream of mine to see what happened if all these talented people got a chance to develop. I was around a very heterogeneous group of artists at that time, and somehow they managed in such a small space. After Bjarne’s studio, we didn’t have twenty-five-thousand square feet anymore. We had like six-hundred square feet, on 14th Street. I had Bjarne curate one show there during Frieze, and people would come in and see Uman’s works. Some collectors from Texas came in, and they didn’t even ask the price. They knew it was what they wanted. Later, one of my friends offered to empty her photography studio for us as long as I would paint the walls and prepare everything and put it back in place once we were finished. I went to every gallery that I could imagine would be interested in self-taught artists, including Matthew at White Columns. But nobody came. Then one day, a lady walked in with an ego so huge that the walls had to make space for her. She stomped in, took one incredibly fast scan, zoomed in on two pieces of Uman’s and said, “Those are mine,” and stomped out. I was like, “Who the hell is this?” Through some connections in the art world, I found out it was Andeville Poiret. I found her and pinned down the sales, and then I was able to call Matthew again and all the others and say, “Excuse me, Andeville Poiret already bought two pieces,” and that’s when you came.

Higgs: I don’t remember the Poiret part of the story, but I do remember coming late. Then visiting the studio and seeing all of these works in what could be described as sort of compromised circumstances, and a word you mentioned earlier that strikes me is clarity—the clarity of Uman’s thinking, wholly present in the work. We ended up making a show relatively soon after at White Columns, which was Uman’s first solo show.

Uman: When you offered me the White Columns show, I was driving back upstate, and I was euphoric. I started working the minute I got home. I worked outside at the time, and had a tiny room in a three-bedroom house that was my studio. The White Columns show came directly out of that small room. I used everything, including the ceiling. It’s a weird thing when you just feel lost for so many years and then all of a sudden you know exactly what you want to do. When I look back, I wish I waited a year because it was such a short period to prepare, from June to September, and I could have done better. I’m constantly thinking this way. I can be embarrassed about the things I did ten years ago. It’s a strange feeling, but I’m also very proud of that show for what it was.

The Bellevue Sobriety Garden, New York, 2024. Photo: Uman

Uman in her studio, Albany, New York, 2022. Photo: Luigi Cazzaniga

Higgs: From that show, you started to have other opportunities, with the David Furman Gallery in Paris and Greece and, more recently, with Nicola Vassell and Hauser & Wirth. How did becoming public or visible through your work, when you’d spent so many years not being visible, affect your way of working?

Uman: There was a part of me that was so free at one point. Now, even just being on social media, I’m like: “Oh, I can’t share certain things about my life or what I’m working on.” Of course, I always wanted to be a successful, well-known person, but it’s very different when it comes to the work. I’m very conscious about everything and self-conscious about everything at the same time.

Higgs: On the acknowledgments page of the catalog you made with Nicola Vassell, you thank a town, Roseboom, New York, a tiny upstate place with a population of 650 people where you’ve made your home. It’s interesting to me. For the most part, in recent years, you’ve worked in a rural or intentionally removed context. You’ve chosen to create circumstances that allow you to work, and those circumstances have informed the work.

Uman: I wanted to come to New York all my life, but at a certain point I realized that there was something about working in the country. It’s like I don’t have any—inhibition is the wrong word, but—

Miescher: Inhibition isn’t a bad word, because you remain a very private person, even though your art is now all over the world. It seems like it’s your responsibility to that incredible gift that nature gave you.

Uman: I do want a private life. I cringe when I see the videos of me and things like that. I don’t know what it is. My biggest dream would be to be a hermit and paint and show my work and not have to be so exposed. Even a talk I did in London was so different for me. I’ve never done anything like that.

Higgs: In front of an audience with the work behind you?

Uman: And the random questions. I still think about some of those questions to this day, six months later. I have control when I’m up here working, and a little bit of privacy.

“It’s interesting to me. For the most part, in recent years, you’ve worked in a rural or intentionally removed context. You’ve chosen to create circumstances that allow you to work, and those circumstances have informed the work.”—Matthew Higgs

Higgs: On a couple of occasions I’ve heard you describe all of your work as a kind of self portraiture. And this morning you suggested to me that you’d like to move away from that idea, that it’s not so important that the work is legible in that sort of biographical sense anymore—that you’re at a point now where maybe it’s time for the story of your life to move behind the work, or elsewhere.

Uman: Yeah, that’s the goal. To be separate from the work. That’s one of the things I really wish, to just be a painter instead of having multiple things added to that: my nationality, where I’m from, etc. I don't think that’s too much to ask. But the world wants to categorize you.

Higgs: You would rather that the work function on its own?

Uman: I want to push and continue to grow, and that means I have to take myself out of the work. It’s something I’m interested in, how much to add or remove myself. This is what I’m going to be experimenting with over the next half of the year.

Higgs: There’s an upcoming survey exhibition of your work, next year at the Hessel Museum at Bard, which will bring together all of these threads from the past decade. It seems like an interesting moment to step back, or to the side, or around, the work, and all of the circumstances that informed it, and have another kind of clarity about where you are now. To have a first survey exhibition seems incredibly useful.

Uman: I went to visit the museum and when I was driving back here I felt a little sad. I was like: “This feels like the end of my career!” But a survey is useful, you’re right. I think it will be good. And we’ll also have the opportunity to contextualize the work and talk more about it.

Higgs: It’s interesting that it’s happening upstate.

Uman: When the curator Lauren Cornell offered me the show last year, I said it was the best gift I could get, to have a first survey in upstate New York. I love upstate New York. It’s the place where I’ve lived the longest, having been a nomad most of my life.

--

Uman's visual vocabulary reflects her life and expansive cross-cultural experiences. An intuitive artist, she draws from memories of her East African childhood, a rigorous education in traditional calligraphy and a fascination with kaleidoscopic color and design. Her work contemplates both the physical and the spiritual, intertwining abstraction, figuration, meditative patterning and a reverence for the natural world.

Annatina Miescher is a Swiss-born, naturalized American psychi-atrist and retired clinical assistant professor at New York University. She ran Bellevue Hospital’s chemi-cal dependency outpatient program from 1987 to 2010, and with her patients she created the Bellevue Sobriety Garden. In 2012, artist Bjarne Melgaard invited her to bring self-taught artists to his studio to collaborate, after which she founded an artist collective to allow these artists to continue developing their skills.

Matthew Higgs is the director and chief curator of White Columns, New York’s oldest alternative art space, where in 2015 he organized the artist Uman’s debut solo exhibition. Since 1993, Higgs has curated more than 250 exhibitions and projects in North America and Europe, and his writings have appeared in more than fifty publications and magazines.