Books

The Artist’s Library: Anj Smith on Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Speak Memory’

Anj Smith, Flowering of the Chocolate Cosmos (detail), 2020 © Anj Smith. Photo: Alex Delfanne

For the first installment of ‘The Artist’s Library,’ a new ‘Ursula’ series in which writer and editor Sarah Blakley-Cartwright will talk to artists about a favorite book on their shelves, Blakley-Cartwright and artist Anj Smith dive into Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Speak, Memory,’ parsing the synesthetic and linguistic pleasures of the writer’s prose. ‘Speak, Memory’ is a memoir of Nabokov’s childhood and adolescence in Russia and in Europe, focusing largely on his happy years as the eldest of five children in an aristocratic family in Saint Petersburg before fleeing the Red Army in Russia in 1917. The book includes 15 episodic chapters published individually, mostly in ‘The New Yorker’ magazine between 1936 and 1951, to create the first edition in 1951.

Anj Smith: I first read ‘Speak, Memory’ a few years ago. I was packing to go on holiday and swept a whole pile of books from my bedside into a suitcase, and that was one of them. At first, I was reading pretty casually until I got to the writing on synesthesia. It just rang so true. I didn’t really know much about synesthesia, and I had this moment of recognition: Oh, wow, that’s exactly what I experience. So, I began reading quite closely.

Sarah Blakley-Cartwright: Synesthesia, as I understand it, is a sensory condition, a blending of the senses.

AS: Your sensory perceptions are fused sometimes. So, for example, ‘Wednesday’ for me is a kind of orangey, amber color. The fact that he could put into words something that was so intangible with such clarity and with such eccentricity, with a real lightness of touch; that’s what drew me in.

SBC: It can also express itself, I hear, as a sort of Proustian ‘madeleine,’ wherein a certain taste can usher in memories. In Nabokov’s case, he saw colors in the alphabet, and he heard language in color.

AS: I think that really comes across. These vignettes are full of color and luminosity. It’s a real painters’ book. I have read ‘Speak, Memory’ twice now, and the first time, I loved certain passages, but there were some parts of the book that left me stone cold. In one part that springs to mind, he starts to go into detail about lots of different relatives, but never developed a full portrait. I just couldn’t work out why he’d included that in the book. It seemed a bit dry, almost to the point where I was thinking of giving up on the book. But when I revisited it, I felt such an overwhelming sense of sympathy for the man. I thought, ‘My goodness, this is a kind of longing to memorialize relatives and a family that’s gone and, more than that, the Russia that is gone forever.’ Here he was in exile, and it’s very poignant, a yearning for something that’s transitory. I think that’s the hallmark of really good art, whether it’s a text or a painting or dance or a performance or whatever: Something that you can revisit and it speaks to you again, differently, in the new experiences that you’re bringing to it. There’s a kind of magical longevity about that.

First edition of Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Speak, Memory,’ published by Putnam Books in 1966

Vladimir Nabokov as a child, no date. Photo: SPUTNIK / Alamy Stock Photo

‘Now and then, shed by a blossoming tree, a petal would come down, down, down, and with the odd feeling of seeing something neither worshiper nor casual spectator ought to see, one would manage to glimpse its reflection which swiftly—more swiftly than the petal fell—rose to meet it; and, for the fraction of a second, one feared that the trick would not work, that the blessed oil would not catch fire, that the reflection might miss and the petal float away alone, but every time the delicate union did take place, with the magic precision of a poet’s word meeting halfway his, or a reader’s, recollection.’

SBC: Can you tell me what you love about this passage?

AS: I think it encapsulates, in that beautiful image, the concrete phenomena of a petal falling, and then the intangible phenomena of the reflection coming to meet it. For me, that’s the work of art. You have the text or the painting—the petal—and then you have the reflection, which is the consciousness that the work of art brings to blossom in the viewer’s mind, or where the reader’s mind comes to meet it. And you need both halves of these things for the work of art to exist. I’ve never read a more beautiful text. And it’s one sentence! Absolutely extraordinary. It’s just so inspirational for me to think about while I’m making work in the studio.

SBC: The sentence almost blossoms like the tree. This notion of simultaneity seems to be a good way into the next passage.

‘I confess I do not believe in time. I like to fold my magic carpet, after use, in such a way as to superimpose one part of the pattern upon another. Let visitors trip. And the highest enjoyment of timelessness—in a landscape selected at random—is when I stand among rare butterflies and their food plants. This is ecstasy, and behind the ecstasy is something else, which is hard to explain. It is like a momentary vacuum into which rushes all that I love. A sense of oneness with sun and stone. A thrill of gratitude to whom it may concern, to the contrapuntal genius of human fate or to tender ghosts humoring a lucky mortal.’

SBC: He is a magician of time. We almost enter slow-motion there. We step outside of the scene.

AS: I love that image of the magic carpet; it’s so evocative. Particularly the way he describes folding it so that you can’t see that there’s been this fold. That’s very Nabokovian. But somehow, in this very simple image, he manages to articulate the complexity of time. Because time is a bit of a mystery, isn’t it?

SBC: In the novel ‘Ada,’ Nabokov writes, ‘The present is only the top of the past, and the future does not exist.’ He creates his own units of time, which are subject to the meter of memory.

AS: I’ve just been reading scientific journals about experiments that physicists are undertaking, to do with ‘superpositioning,’ where photons have been photographed in different places at the same time. The same photon! And I’ve been reading about how clocks run faster on the top of a mountain than they do at sea level. My understanding of relativity is incredibly elementary, but I have also read that the equations that govern those laws can be reversed, which is problematic if you think about ‘the arrow’ of time. So, it’s an artificial construct that is also a fundamental aspect that governs all of our existence.

Anj Smith, Opera Aperta, 2017–18 © Anj Smith. Photo: Alex Delfanne

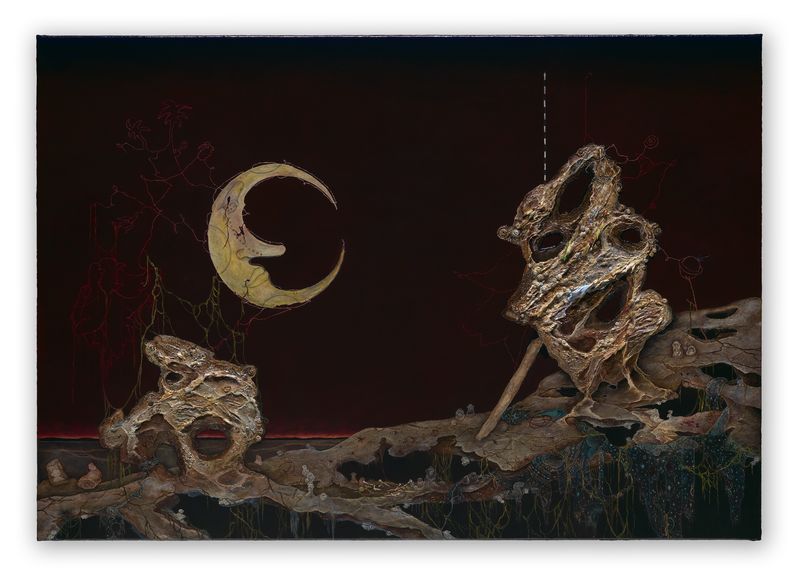

Anj Smith, Flag and Ball, 2017–18 © Anj Smith. Photo: Alex Delfanne

SBC: Art and memory are ways that clock time is subverted. Memory is flawed because time passes, but time is also always being encroached upon by memory. They’re each constantly giving way, or giving primacy, to the other. Exactly what you’re talking about, this notion of an infinite past and future, the folds closing over each other so that you don’t even see where they begin and end. I’m struck by the poetry of the arrangements in the scene you just read, of the themes and patterns of the perception. All this seems central to Nabokov’s articulation of time. He stands far outside the scene while being right at the center of it.

AS: He talks about time as though he were able to stand outside of it, but of course he’s not. It’s almost as though he’s drawing a portrait of it, but you can’t draw a portrait of anything in its entirety, unless you can step back, and you can’t step back from these things. But I do think that’s where his genius comes in to play; he gives you not only the illusion of being able to do that, but also that it is something that you’ve experienced—personally—in the way he’s described it.

SBC: If time does not exist, then you can always gain back what is lost. There’s a passage in another chapter where his father is being tossed up into the air by the villagers living on their estate, in celebration of something wonderful he has done for them. And, in the space of a paragraph, we go from the father thrown up in the air, recumbent, this glorious vision of him in his full health, to a body laid out on a bier in a church and the candles flickering, which anticipates his father’s open coffin. That spiral-like mode of time, time’s continuance, is a way to retrieve the irrevocable. You have snail shells, for instance, in the painting ‘Opera Aperta,’ and you have spirals in the painting ‘Flag and Ball.’ I’m curious what this vorticity is adding in your work?

AS: The spiral is an interesting shape in general; it’s very dynamic. Elsewhere he describes the spiral as a ‘spiritualized circle.’ So there’s the formal consideration of it, but it’s a maze, isn’t it? And it’s also a cartoon shorthand for a hallucination or psychedelia. It’s transporting you from one mode into another.

SBC: It’s concentric, so you don’t realize that you’re getting somewhere, but you are.

AS: Absolutely. And you’re locked in. He describes his life as the little swirl of color in a glass marble. It’s beautiful, but also a slightly treacherous image, because he’s trapped.

Anj Smith, Flag and Ball, 2017–18 (detail) © Anj Smith. Photo: Alex Delfanne

SBC: We all think we want to crawl inside a snow globe, but do we?

AS: Exactly. There’s a slightly horrifying tint to what appears initially as a very charming image. One thing that I find interesting in this text, but also thinking about painting in general, is that painting can facilitate worlds within worlds. I love that idea. Towards the end of Chapter Two, he describes this beautiful sunset. And right in the middle of the sunset, there’s a miniature landscape glimpsed within the clouds. It’s so beautifully written. But that’s the logic of painting! You have this flat plane, but you can have these portals of logic that pop up and exist at any time. And I think that’s one of the great pleasures of painting. It’s just not linear in that way, and this book isn’t either.

‘Now that I come to think of it, how tawdry and tumid they looked, those jelly-like pictures projected upon the damp linen screen. More moisture was supposed to make them blossom more richly, but on the other hand, what loveliness the glass slides as such revealed when simply held between finger and thumb and raised to the light. Translucent miniatures, pocket wonderlands, neat little worlds of hushed, luminous hues. In later years, I rediscovered the same precise and silent beauty at the radiant bottom of a microscope’s magic shaft. In the glass of the slide meant for projection, a landscape was reduced. And this fired one’s fancy, under the microscope, an insect’s organ was magnified for core study. There is, it would seem, in the dimensional scale of the world, a kind of delicate meeting place between imagination and knowledge, a point arrived at by diminishing large things and enlarging small ones that is intrinsically artistic.’

SBC: Beautiful. What especially speaks to you in this passage?

AS: I love the phrase ‘a delicate meeting place between imagination and knowledge.’ That’s an articulation of the artist’s headspace when they start thinking about making a painting. As for ‘diminishing large things and enlarging small ones,’ I suppose, for me, when he talks about scale, it’s describing a way of stepping back from the memory and then reappraising it. It’s as if he’s turning over things in his mind, a bit like examining a memory as though it were a jewel and looking at it through lots of different facets.

SBC: A kaleidoscopic, splintered vision. A magic lantern display.

AS: Yes. And examining the nature of ‘reality’ through that and not relying on any one depiction of it to carry the whole, because that would be an impossibility.

SBC: Tell me about the rhythmic reiteration in your work, especially in your latest, about scale.

AS: I still work on a small scale, sometimes. A small painting can pack an extremely powerful punch, possibly more than a painting that’s so large you can casually pace by and take it in in a few seconds. A small painting can demand of the viewer what Nabokov’s very dense passages demand of a reader—you have to sit there and read it. It’s a kind of riposte to a cultural conditioning where everything we receive in terms of data points is quite shallow and constantly refreshed. I’m thinking about my Instagram feed or the way that we consume political reporting. As long as something is easily consumable, it tends to be what we’re given, regardless of whether it’s actually got that much content if you unravel it.

Anj Smith, Untitled (Mayday), 2011-2020 © Anj Smith. Photo: Alex Delfanne

SBC: Do you find that content has any usefulness to your work? Soundbites, bits and pieces of perception, Instagram feeds?

AS: I’m working in opposition to those shallow, constantly evolving, bite-size chunks. I think more about being aware of this moment that we’re living in and expanding our knowledge banks. And that takes time, that takes slowing down to spend more time with a painting than just a few seconds. There’s a certain richness to that experience that I suspect we all crave, in one form or another. For me, that is the pleasure of this book. You can’t flick through it. You have to sit with it and ask yourself questions as you’re reading it. And then you get the huge reward. Assumptions that I’ve had about various things start to crumble away, conventional thinking starts to dismantle, and the way that I might think about time or memory broadens… which [the filmmaker] Andrei Tarkovsky described as two sides of the same medal. I think that’s really lovely, because they are both so interrelated, aren’t they?

SBC: I know you selected Tarkovsky’s ‘The Mirror’ [1975] for Hauser & Wirth’s Artist’s Choice Summer Film Series. I’m curious about what speaks to you in the film. Do you feel that these two works are talking to each other?

AS: I don’t know that they talk to each other, but possibly I get the same thing from both of them—that the narrative is fractured. And, in Tarkovsky, I guess it’s that rhythm, the important rhythmic motion that’s referencing time passing.

SBC: Between time frames and even between archival footage and recorded dramatic footage.

AS: I like the fact that if you were to have addressed that subject matter head on, it wouldn’t convey the whole that is conveyed by using this kind of fragmentary approach. In both ‘The Mirror’ and ‘Speak, Memory,’ there’s so much that’s omitted. And that quite powerfully articulates that we will never know the full picture. The lusciousness of the cinematography in ‘The Mirror’ and the text of ‘Speak, Memory,’ for me, validates our attempts at making art, reading books, or watching films. It validates our thought processes, the fact that we might not have all the answers, but we’re asking the questions. And I find that incredibly touching.

SBC: And both of these works—with all their eminent craftedness—create a complexity that leads to a certain simplicity. It’s really a coherent, organic reproduction of consciousness and, like you said, that rhythm. It’s the impression that time makes.

AS: I don’t think technical skill is the most important currency when it comes to a painting. However there is something to be said for that kind of virtuosity. And when you consider ‘The Mirror’ and ‘Speak, Memory,’ you see that these artists were at the top of their game. They had mastered every skill in the book, and they could use that as a springboard to leap off to dizzying heights and take us with them.

SBC: We’re lucky to go along for the ride. His novels are full of asides and disclosures and fragments, and yet all of it is meticulously wrought. I’m thinking about the idea of veiling, which is a sort of leitmotif that recurs in your work and of course brings us back to some of those Renaissance or early Netherlandish paintings. I’m thinking of Rogier van der Weyden, his gorgeous ‘Portrait of a Lady’ in the National Gallery, with her translucent veil. What does a veil bring to a portrait?

Rogier van der Weyden, Portrait of a Lady, ca. 1460. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

AS: I suppose most often they walk that line between, is this armor, or is this some kind of protective thing? Is this person vulnerable? Or is it a deliberate obscuring? Is this a protection of privacy, a sort of a powerful gesture? The veil is very ambiguous, and I think this applies to the gaps in ‘Speak, Memory,’ the things he doesn’t include. For some reason, the gaps and the veil articulate so much in the fact that they obscure. That in itself is quite interesting as a grammar of the unknown. Do you remember that bit where he kisses his mother? She’s in a sleigh, wrapped in her seal furs. She’s this incredibly glamorous figure, and he goes to kiss her. He’s describing his mother arranging her veil after she’s been into a shop. He says,

‘I watched, too, the familiar pouting movement she made to distend the network of her close-fitting veil drawn too tight over her face, and as I write this, the touch of reticulated tenderness that my lips used to feel when I kissed her veiled cheek comes back to me— flies back to me with a shout of joy out of the snow-blue, blue-windowed (the curtains are not yet drawn) past.’

I think it’s an absolutely exquisite little vignette. The veil is just so cleverly employed, because he can’t get back to that past to kiss her.

SBC: The thematic layering and the physical layering. I love what you’re saying about these gossamer facades. They’re almost a false front. As you paint them, they’re filmy and gauzy, nearly transparent. What is it that appeals to you about painting transparency?

AS: In a new painting I’m working on [‘Flowering of the Chocolate Cosmos’], I’m imagining a scenario where something has frozen and thawed out and then frozen again and thawed out. And in this painting, there’s a sort of ‘homemade’ liqueur made out of violet petals that have been strewn and spilled across another patch of ice. Underneath the ice, there is a Chocolate Cosmos flower, which is a beautiful Mexican flower that gives off this absolutely exquisite perfume, a very chocolatey smell. It’s funny because I started thinking about this work before the lockdown, but it’s become a kind of self-portrait. And chocolate—which is a sort of shorthand (in my world anyway) of joie de vivre and comfort and luxury and pleasure—is trapped underneath these layers of ice for now. But the ice is starting to thaw, and the petals are starting to emerge. Painting this work in lockdown, has given it this whole new context. I’m out of my studio for the moment, so I’m painting at home. I’m looking after my family during the day, then at six o’clock, I go upstairs to the attic and work into the early hours, which if I’d thought about previously, I would have thought absolutely exhausting and quite horrifying and depleting. But the reality is that, so far, it’s been quite the opposite. It’s been an absolutely invigorating experience—to realize that I can still work, even like this—although quite an intense one. And that quality of it, that sort of approach that I’m bringing to it every evening, is really showing in the work.

SBC: That ice melting to water, the disorienting, transitional boundaries that show up in your work and in Nabokov’s, too. I’m thinking, too, of the precarious structures that show up in your works, whether they are moth-eaten or decomposing or moldering or withering, or fabric that’s torn or is disintegrating. What is it that’s most evocative for you in these representations of decay or transition?

AS: There are different things at play in different works. Sometimes it is to signify that time is behaving in a strange way. So you might have a rotting fruit that is decaying at a slower rate than a piece of fine jewelry, for example. One of the things that I treasure about art, looking at art as well as making it, is this facility. We touched on this earlier—dismantling conventional thinking and really challenging everything we’ve drawn certain conclusions about. That is quite a precarious place to be psychologically, because most things can become calcified if you don’t look back and reassess. Art can speak to that and change the way that we look at the world and the way we experience things.

SBC: Transparency and veiling are key to Nabokov’s notorious authorial manipulations. The characters and the author are obfuscating, the author as an arbiter between reader, and the characters serving as a veil. I also think Nabokov’s humor often serves to veil sadness.

AS: That’s interesting you should say that. I wanted to recommend a book that would be quite life-affirming and joyous in places. It struck me as extraordinary that he’s writing about the trauma of having to leave his homeland. He speaks quite matter-of-factly about bereavement and his family being totally ruined. They had to leave everything behind, and lots of his family were killed—the trauma he must’ve experienced, and the sadness and the loss—but he seems to deliberately not go there in this book. All of these vignettes are incredibly luminous and charged with this great beauty. It’s almost as though he’s writing from a point of view where he just wants to celebrate and rescue the life of these things. I started thinking about moments in my own life when I’ve experienced trauma or have gone through incredibly difficult times. And I wondered if precious, joyous fragments were what he decided he wanted to reassemble and hold on to, and perhaps that’s why this novel is such an incredibly energizing and positive read, despite the roots of where it comes from.

SBC: He has this incredible lightness of hand where, even in his most dynamic, vigorous, buoyant sections, there is always this sense of the underpinning of the exile’s sense of dislocation and interruption and disruption. That doesn’t take away from our sense of this effervescence of the happy childhood, but it’s there.

AS: You’re right. I think that’s probably where his alienation comes into play. He’s always on the sidelines looking in, in pretty much every scene.

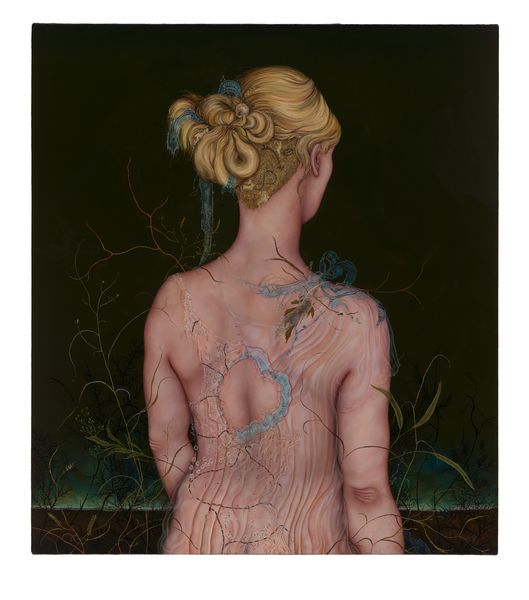

SBC: It’s the spiral. He’s always apart, but he’s also in the middle. Which, of course, is a profoundly disorienting place for him to be. Mental health is a great topic of Nabokov’s. I know you’ve shaped certain shows around your experience of anxiety, including in 2018, ‘If Not, Winter.’ In your painting ‘Opera Aperta,’ there’s an interconnected web of symbols—rhomboids and lips hang in a scaffolding and sort of swarm around the figure. And in your painting ‘Taste,’ symbols are carved into the figure’s hair or tattooed on the scalp. Could you talk a bit about these unsettling and hidden forces?

AS: Anxiety is not something I’d wish upon anyone, obviously, but it has been enormously interesting in the context of the work. I’ve experienced this thing called inferential confusion, which is where, in the moment, you’re not entirely sure what is reality and what is fantasy. It’s typically an anxiety, a completely irrational anxiety that seems highly probable to you. And after coming out of that kind of mentality, there’s a sort of questioning of ‘reality’ that remains. Recovering from those episodes has given me a lot of clarity. A lot of my work is underpinned by two basic philosophical questions: What is there? And if anything, what is the nature of that thing? They’re so simple, but they’re so impossible.

Anj Smith, Flowering of the Chocolate Cosmos, 2020 © Anj Smith. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Anj Smith, Taste, 2017 © Anj Smith. Photo: Alex Delfanne

‘The mysteries of mimicry had a special attraction for me. Its phenomena showed an artistic perfection usually associated with man-wrought things. Consider the imitation of oozing poison by bubble-like macules on a wing (complete with pseudo-refraction) or by glossy yellow knobs on a chrysalis. (‘Don’t eat me—I’ve already been squashed, sampled, and rejected.’) Consider the tricks of an acrobatic caterpillar (of the lobster moth), which in infancy looks like bird’s dung, but after molting, develops scrabbly, hymenopteroid appendages, and baroque characteristics, allowing the extraordinary fellow to play two parts at once… that of a writhing lava and that of a big ant seemingly harrowing it. When a certain moth resembles a certain wasp in shape and color, it also walks and moves its antennae in a waspish, unmothlike manner. When a butterfly has to look like a leaf, not only are all the details of the leaf beautifully rendered, but markings mimicking grub-bored holes are generously thrown in. ‘Natural selection,’ in the Darwinian sense, could not explain the miraculous coincidence of imitative aspect and imitative behavior, nor could one appeal to the theory of ‘the struggle for life,’ when a protective device was carried to a point of mimetic subtlety, exuberance, and luxury far in excess of a predator’s power of appreciation. I discovered in nature the nonutilitarian delights that I sought in art. Both were a form of magic, both were a game of intricate enchantment and deception.’

SBC: Maybe you can talk a little bit about camouflage as a defense mechanism in your work, specifically, ‘Cammo’ and ‘Rings Around the Moon.’

AS: For both paintings, it’s that kind of tightrope walk between a portrait of vulnerability and a portrait of defiance and display.

SBC: Butterflies are so fragile, but they’re intensely strategic.

AS: I see one aspect of mimicry, which is that our perceptions are a copy of whatever ‘real’ event we’re experiencing, and then the art that we make from those perceptions is yet another copy.

SBC: The Platonic idea of mimesis, the re-presenting of nature.

AS: Exactly. I chose this passage because it seems to illustrate that uncanny territory of the natural worlds, the natural kingdoms. Toward the end of Chapter Two, he describes being on the cusp of something, almost being able to see into the future. There’s a kind of sublime that he hints at, and I can relate to that in my own practice because I’m interested in taking the idea of representation to its absolute limit and the extremes of that. And examining the edges of what we know. And of course we never know what the edge is because if we could see the edge then we wouldn't be there.

SBC: Butterflies are a great symbol of transition. They metamorphose and transform; they almost resurrect themselves. They slumber in pupas, these little inactive, immature pouches. And then after its incubation period, a butterfly unfolds and takes flight. They’re figures of fantasy. I know that you’re reluctant to classify your work as fantastical. I wonder if that misapprehension on the part of certain viewers comes from the idea of worlds lying dormant in your work; there are other worlds there, but they go unseen.

AS: Just as you were finishing your last point about butterflies, I was envisaging a cocoon. The thing that I love about the cocoon as a phenomenon is the potentiality. I like the idea of the hidden potential that hasn’t yet unfurled. I can understand the recognition of that in the work.

Anj Smith, Cammo, 2015 © Anj Smith. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Anj Smith, Rings Around the Moon, 2015 © Anj Smith. Photo: Alex Delfanne

‘But the most constant source of enchantment during those readings came from the Harlequin pattern of colored panes inset in a whitewashed framework on either side of the veranda. The garden when viewed through these magic glasses grew strangely still and aloof. If one looks through the blue glass, the sand turned to cinders while inky trees swam in a tropical sky. The yellow created an amber world infused with an extra strong brew of sunshine. The red made the foliage drip ruby dark upon a pink footpath. The green soaked greenery in a greener green. And when, after such richness, one turned to a small square of normal, savorless glass, with its lone mosquito or lame daddy long legs, it was like taking a draught of water when one is not thirsty, and one saw a matter-of-fact white bench under familiar trees. But of all the windows, this is the pane through which in later years parched nostalgia longed to peer.’

AS: Every single word is chosen with such specific care. Like the word ‘amber’ for the yellow pane of glass! That has connotations of the insects trapped in sap and of the inaccessibility of our past, but also of how the memories of that can be a beautiful thing to look back on. And ‘harlequin’—it struck me that traditionally, the Harlequin has a magic wand, he taps the scenery and the scenery changes. And I thought hidden, embedded in this text, there are these little miniature self-portraits. Here he comes as the Harlequin, changing the scenery at a whim, the prerogative of any writer or artist. It’s just absolutely exquisite.

SBC: ‘Amber,’ you’re right—there are novels submerged in that single word.

AS: He makes it look effortless. I think it was [the ballet dancer and choreographer] Rudolf Nureyev who said, ‘Technique is what you fall back on when you run out of inspiration.’ And Nabokov can do the formal structure of the novel backwards, forwards, whichever, but then he just soars above all of that. He can employ it when he wants to and he can dismiss it when he wants to. And that is my ambition for painting. I want to be able to do whatever I want and take people with me on the journey.

‘You remember the discoveries we made (supposedly made by all parents): the perfect shape of the miniature fingernails of the hand you silently showed me as it lay, stranded starfish-wise on your palm; the epidermic texture of limb and cheek, to which attention was drawn in dimmed, faraway tones, as if the softness of touch could be rendered only by the softness of distance; that swimming, sloping, elusive, something about the dark bluish tint of the iris which seemed still to retain the shadows that it absorbed of ancient fabulous forests where there were more birds than tigers, and more fruit than thorns, and where, in some dappled depth, man’s mind had been born; and above all, an infant’s first journey into the next dimension, the newly established nexus between eye and reachable object, which the career boys in biometrics or in the rat maze racket, think they can explain. It occurs to me that the closest reproduction of the mind’s birth obtainable is the stab of wonder that accompanies the precise moment when, gazing at a tangle of twigs and leaves, one suddenly realizes that what had seemed a natural component of that tangle is a marvelously disguised insect or bird.’

SBC: That’s such a great evocation of the evolution of consciousness: an image that comes clear. I’m thinking of transitions here, and how art itself changes the way we see. Can you put a finger on specific moments when art awakened something in you?

AS: I mean, all the time. I think art has given me a kind of reassurance, in providing language to express what I’d assumed in childhood to be inexpressible. It’s more like, ‘Ah, okay. I’m not alone.’ When I think about experiencing Louise Bourgeois’ work for the first time, it was like an arm around the shoulder, and absolutely galvanizing. I do not come from a background where we read Nabokov or went to galleries. That was outside the frame of expectation. Art has opened up to me the pleasure of acquiring knowledge and it's something that obviously continues to evolve.

Anj Smith, Night in May, 2017 © Anj Smith. Photo: Alex Delfanne

SBC: I’m thinking about not being sure what we’re seeing, and the way that nature and art both often hide their riches in plain sight. Oysters and pearls, let’s say. And I’m thinking of your painting ‘A Night in May.’ It’s a recurrent experience in your work: something that at first looks like a log seems to be dripping with untold treasures. But then, wait a minute, is that a disease that’s eating up the log? I’m curious what you gain from keeping the viewer from being exactly sure what she’s seeing.

AS: I think you can say more by the circuitous route than the direct path, which is exemplified by the texts we’ve been discussing. The same is true for me in painting. I personally respond to work that is not that easily digestible and unfolds over time. And that’s why perhaps I employ some of the language that I do. Again, I guess that is partly a product of my frustration with this kind of dumbing down that I feel like we’re experiencing culturally. Certainly here in the U.K., we’ve become used to emptied-out political rhetoric, which sounds good on the ear, but has had disastrous consequences in real life. So I suppose I’m making work directly in opposition to that; it’s a plea for savoring knowledge and expertise and slowing down and valuing these things enough to do so.

SBC: I’m thinking of lenses, which Nabokov nods to with his colored glass diamonds, his microscope, and then, of course, of his very myopic characters, Humbert and Kinbote, completely deluded and shortsighted. Translation itself is a lens, just as consciousness in this portrait of his youngest son is a new language he’s learning as his eyes adjust. Nabokov translated ‘Speak, Memory’ back into Russian in 1954, so with the revisions he made in 1966, the book was told three times. Autobiography and translation are both ways to get outside of yourself. Always, he’s outside and inside the scene. I’m curious about the role of the self in your work and whether you use certain devices to get outside yourself.

AS: It feels so constantly present that it’s a shock to realize that you do step outside of the work, but of course you do as an artist. And it’s important to live life so that the work is authentic and relevant. There’s been an unexpected aspect of domesticity at play recently thanks to lockdown, as I’ve got lots of very small children. It has forced me to take a complete firebreak in terms of the kind of thinking I’m doing in the studio. I’m not one to downplay the toll that can take on an artist, especially women—and I’m absolutely feeling that right now—but what I would say, in terms of stepping outside of the work, the cliché of ‘the pram in the hall’ isn’t always the full picture. Existing in a different headspace has meant that, when I finally get into the studio hours later, I’m able to go a lot deeper and a lot further with more intensity because of the relief of finally being able to get down to work.

SBC: I love the image of Nabokov in his bathtub drafting on the index cards, which are now at the New York Public Library in the Berg Collection. Maybe we can end with an image of your working process, of how you’re painting at the moment.

AS: I’m working at night, as I mentioned. And funnily enough, it’s been a huge relief to find I’m able to work, because it’s a complete change of routine. I guess the discipline of 20 years of practice has meant that it’s going to take more than this situation to make a dent in that kind of commitment to the work. One thing I do, much to the irritation of everyone around me, is to keep a journal on my phone, and I have numerous sketchbooks that I’m constantly writing in as well. So I can relate to the bathtub thing in the sense that you never switch off as an artist. That can be exhausting sometimes. You’re constantly storing away things that people are saying or looking at something that sparks a myriad of ideas. And I look at everything with a filter on, for example in the manner in which I’ve read this book. The filter is always, ‘How does this apply to my painting? How does this apply to painting in general?’ That doesn’t get switched off. But I wouldn’t have it any other way, of course.

Anj Smith is a British painter whose intricately rendered works explore issues of identity, eroticism, mortality, and anxiety. A major solo exhibition of the artist's work opens Spring 2021 at The New Art Gallery Walsall.

Sarah Blakley-Cartwright is a New York Times bestselling author. She is Publishing Director of the ‘Chicago Review of Books’ and Associate Editor of ‘A Public Space.’ Excerpts from ‘Speak, Memory: An Autobiography Revisited’ by Vladimir Nabokov © 1947, 1948, 1949, 1950, 1951, 1967 by Vladimir Nabokov, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC and Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.