Essays

David Smith: A Timeline

David Smith with Cubi IX (1961) and Two Circle Sentinel (1961), Bolton Landing, NY, ca. 1961. Photo: David Smith. All images © 2020 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Over a 33-year career, American artist David Smith expanded the notion of what sculpture could be, redefining its relationship with the space it was created in and its final habitat. Combining abstraction and poetic figuration, Smith’s deeply humanist vision has inspired generations of sculptors in the decades since his death. To mark the opening of our online exhibition ‘David Smith. Sprays’ dedicated to his series of works in the medium of aerosol paint, Jennifer Field, Executive Director of The Estate of David Smith, shares a chronology of the life and work of this pioneering twentieth-century artist.

1906

Roland David Smith is born on 9 March in Decatur, Indiana.[i] ‘When I was a kid,’ Smith later recalls, ‘everyone from the whole town was an inventor. There must have been fifteen automobiles made in Decatur, Indiana, and they were all put together in parts by all kinds of people. Just two blocks from where I lived there were guys building automobiles in an old barn. Invention was the fertile thing then. Invention was the great thing.’[ii]

1924 – 25

Smith begins college at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. He takes a summer job at the Studebaker automobile factory in South Bend, Indiana. He learns spot welding and how to work a lathe and a milling machine in addition to riveting, drilling, and stamping.

1926 – 27

Smith moves to New York City. He meets artist Dorothy Dehner and, at Dehner’s encouragement, enrolls at the Art Students League, where he studies painting and takes a woodcut class. Smith and Dehner marry the following year. They will divorce in 1952.

David Smith, Untitled (Virgin Islands Tableau), Gelatin silver print, ca. 1931 – 1932

David Smith. Untitled (Virgin Island Landscape Coral), ca. 1933. Estate of David Smith, New York, NY. Photo: Christopher Burke

1928 – 30

Smith exhibits in a group show at the Art Students League and takes a drawing class. He studies painting with Czech artist Jan Matulka until 1931—a period of his art education that Smith will later call the ‘Great Awakening of Cubism.’[iii] Matulka encourages Smith toward abstraction and the use of unconventional materials such as paint scrapings and sand. Smith meets artist and theorist John Graham, who introduces Smith to Milton Avery, Stuart Davis, Arshile Gorky, and Willem de Kooning. Smith and Dehner move to Brooklyn. In 1929 they purchase an old fox farm in Bolton Landing, in the Adirondack Mountains of New York, where they spend their summers.

1931 – 32

Smith and Dehner leave for an eight-month trip to the Caribbean, staying mainly in St. Thomas. Smith begins to make sculpture using found materials and to experiment with photography using techniques involving double-exposed negatives and photo-collage. He also makes a group of painted landscapes featuring overlapping planes of ‘water, shoreline, and mountains converging in sensuous, flowing skeins….’[iv] At Bolton Landing, Smith begins to convert a woodshed into an art studio.

David Smith with his sculptures at Terminal Iron Works, Brooklyn, NY, ca. 1937. Photo: David Smith

1933 – 34

Smith continues making sculpture using found objects and scrap iron. In the journal ‘Cahiers d’Art’ Smith sees an example of Picasso’s welded sculpture. ‘When I saw that art was being made with material I knew and could work,’ Smith would later explain, ‘it appealed to me immediately. So from then on, I was a sculptor.’[v] Smith begins making sculptures at Terminal Iron Works, a commercial machinery along the Brooklyn waterfront. The location provides him with a space outside his apartment to safely continue welding. ‘I walked in and was met by a big Irishman named Blackburn,’ Smith would later recall. ‘I’m an artist, I have a welding outfit. I’d like to work here.’ ‘Hell! yes—move in.’ With Blackburn and Buckhorn I moved in and started making sculpture there. I learned a lot from those guys and from the machinist that worked for them named Robert Henry.’[vi] Smith will later name his Bolton Landing workshop ‘Terminal Iron Works.’

1935 – 36

Smith and Dehner travel for nine months through Europe, spending time in France, Belgium, Greece, Russia, and England. In Paris, Smith makes etchings at Stanley William Hayter’s print workshop Atelier 17 and sees the important ‘Exposition surréaliste d'objets’ at Galerie Charles Ratton, organized by André Breton. The exhibition is known for presenting, as a full environment, a range of non-Western and utilitarian objects as well as subversive Surrealist sculptures and assemblages.

David Smith welding at American Locomotive Plant, Schenectady, NY, ca. 1943

David Smith welding Star Cage (1950), Bolton Landing, NY, ca. 1950. Photo: David Smith

1937 – 38

Smith makes sculpture in the mural division of the Federal Art Project under the WPA (Works Progress Administration), a program initiated by Franklin D. Roosevelt to stimulate economic recovery in the post-Depression era. He has his first one-person exhibition at Marian Willard’s East River Gallery on 57th Street.

1939 – 40

Smith begins to earn critical recognition for his work in sculpture. He makes a group of sixteen plate-sized bronze casts titled ‘Medals for Dishonor’ depicting the atrocities of war, as a statement against the Fascist forces behind World War II. After Smith is laid off from the WPA in 1940, he and Dehner make Bolton Landing their permanent residence.

1941 – 42

The U.S. enters World War II. Smith takes classes in machinist work and electric welding in the hope of finding employment in the war industry. He finds a job as a welder at American Locomotive Company in Schenectady, New York.

David Smith, Cooperation of the Clergy, 1939. Estate of David Smith, New York, NY. Photo courtesy the Fogg Museum

David Smith, Race for Survival (Spectre of Profit), 1946, Bolton Landing, NY, ca. 1946. Photo: David Smith

1943

Upon seeing a sculpture by Smith at the Buchholz and Willard Galleries in New York, Clement Greenberg writes: ‘Smith is thirty-six. If he is able to maintain the level set in the work he has already done… he has a chance of becoming one of the greatest of all American artists.’[vii] The Museum of Modern Art purchases ‘Head’ (1938), the first of Smith’s works to be acquired by a major institution for its permanent collection.

1944

Smith quits his job at the locomotive factory and focuses full-time on making art. He does general repair work for the local public to help fund his practice. Expanding on the theme of a sculpture he made during his WPA years, ‘Spectre of War’ (now lost), Smith begins a group of sculptures known as ‘Spectres’ in response to the anxiety of war.

1945

Smith begins to work with stainless steel. He also takes up the practice of routinely photographing his sculptures.

David Smith, Interior, 1937. Courtesy The Weatherspoon Art Museum at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

1946

Smith exhibits 54 sculptures alongside drawings at the Willard and Buchholz Galleries in New York City. A review of the exhibition acknowledges ‘all sorts of hidden meanings and symbols that seem to stem from classical mythology, from primitive totems, from medieval architecture—and don’t quite explain themselves.’[viii] Joseph Hirshhorn acquires the first four out of 28 sculptures by Smith that he will eventually bequeath to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

1947 – 49

Smith meets Robert Motherwell, who asks him to contribute to a new magazine, ‘Possibilities.’ He also publishes two poems in the avant-garde periodical, Tiger’s Eye. Smith becomes a visiting professor of sculpture at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, New York. He begins a relationship with student Jean Freas, whom he will marry in 1953. The couple will have two daughters, Rebecca and Candida. Teaching will become an important and gratifying endeavor for Smith; he will take on a number of teaching appointments at various institutions throughout his career.

David, Jean, Rebecca and Candida Smith, Bolton Landing NY, ca. 1958. Photo: David Smith

David Smith painting ‘The Banquet’ (1951), Bolton Landing NY, 1951. Photo: David Smith

1950

Smith receives a Guggenheim fellowship that launches his most productive decade to date. He purchases large quantities of steel and a high-quality camera. He soon begins to increase the sizes of his sculptures to around six feet in height and to produce numbered series of works related in format and scale. Later, Smith will write, ‘When the sculpture is human size or of slightly above human size it presents a personal challenge to the beholder himself. … My sculpture is not made to fit someone else’s space.’[ix] He meets Helen Frankenthaler, who becomes a close friend.

1951

Smith meets Washington, D.C. painter Kenneth Noland. Smith exhibits two sculptures in the exhibition ‘Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America’ at The Museum of Modern Art, which situates him among prominent modernists as well as new artists from his own generation. Alexander Calder, Stuart Davis, Willem de Kooning, Man Ray, Isamu Noguchi, Jackson Pollock, and Joseph Stella are among those included in the show. Smith makes two of his best-known sculptures in a style that has been likened to drawing in space: ‘Australia’ (The Museum of Modern Art) and ‘Hudson River Landscape’ (Whitney Museum of American Art). He begins his ‘Agricola’ series, constructed from found tools and farm machinery. Elaine de Kooning publishes ‘David Smith Makes a Sculpture: Cathedral’ in ‘Artnews’ as part of an ongoing series on contemporary artists from her circle. For the article, Smith describes various processes he employs in conceptualizing a new sculpture, which include making ‘chalk drawings on the cement floor, with cut steel forms working into the drawings.’[x] ‘When it reaches the stage that the structure can become united,’ Smith continues, ‘it is welded into position upright.’[xi]

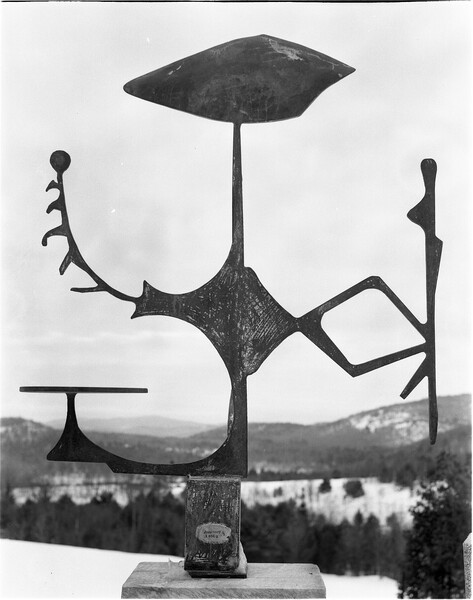

David Smith, Agricola I (1951-52), Bolton Landing, NY, ca. 1952. Photo: David Smith

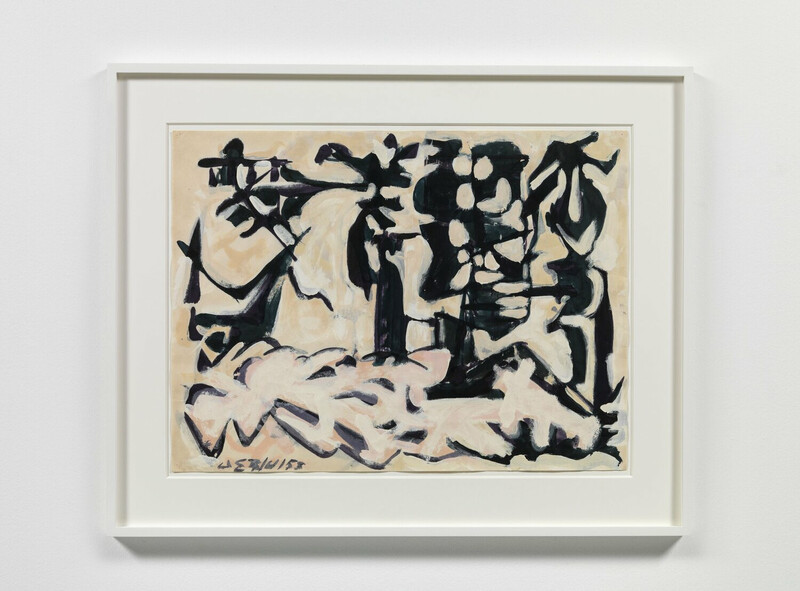

David Smith, Untitled, 1953. Estate of David Smith, New York, NY

1952

Smith receives increasing recognition for his work and a growing demand for public speaking engagements. In a lecture at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine, Smith refutes the idea that abstract art exists independent from nature, a claim he repeats throughout his career. ‘I keep some stones around the house that I bought at the Museum of Natural History,’ he explains. ‘These I conceive of as reality. They are beautiful flowing soft shapes, and wonderful geometry. The critics that say, ‘I don’t like abstract art because it is too far from nature’—I don’t know where they get off with that stuff, because this is nature, too.’[xii] Smith begins a new sculpture series called ‘Tanktotems,’ which are made from industrial tank ends and other geometric steel elements welded together into humanoid constructions. ‘Tanktotem I’ (1952) is among the tallest in the group, measuring 7 ½ feet in height. Smith makes an unprecedented number of works on paper this year. He will produce on average 200-300 drawings per year throughout the 1950s, mostly in black ink that he mixes with egg or casein. He also makes six known lithographs at Margaret Lowengrund’s print workshop in Woodstock, New York.

1953

The exhibition ‘Twelve Modern American Painters and Sculptors’, organized by MoMA’s International Council, tours through six countries in Europe. Smith is represented by six sculptures made between 1942 and 1951.

1954 – 55

Smith teaches sculpture at Indiana University in Bloomington. He establishes a relationship with the august machine shop Seward & Company, where he learns how to use a power forge. Smith makes the ‘Forgings,’ a series of eleven slender vertical sculptures using this technique along with welding. The Whitney Museum of American Art purchases ‘Hudson River Landscape’ and lends the sculpture to the 27th Venice Biennale later this year. Smith travels to Italy, where he sees the work installed in Venice. He also visits Ferrara, Florence, and Milan, and meets Italian artists Afro and Salvatore Scarpitta, among others.

David Smith, Sculpture group, Bolton Landing, NY, 1964. Photo: David Smith

1955

Smith returns to Bolton Landing. He reorganizes his workshop so that he can do much of his machine work in the open air. Smith experiences a surge of productivity and completes over 40 sculptures this year. He begins to arrange his sculptures in the fields around his home. Inside the shop, the increasing size of Smith’s sculptures prompts him to work directly on the floor of his studio in conceptualizing new forms. He paints a white rectangle on the floor as a neutral backdrop, then lays out steel elements on top of it. After determining a final arrangement, he welds the elements together on the floor and raises the sculpture upright, leaving behind scorched silhouettes on the white ground.

David Smith, Untitled, 1959. Estate of David Smith, New York, NY

1956

In what will turn out to be a year of experimentation, Smith begins making abstract oil paintings on canvas in an exaggerated vertical format measuring up to 7 feet in height and less than one foot across—a marked departure from the easel-sized paintings he had been making before this time. In a lecture at Skowhegan, Smith challenges the restrictive conventions of modern painting, saying, ‘I think that tradition has intimidated us in relation to the size of picture we’re expected to paint or the size of sculpture we’re expected to do. … I don’t think people paint big enough.’[xiii] Smith contemplates the function of color in his sculptural work, telling a friend, the artist Herman Cherry, that some sculptures will be painted with oil in an attempt to unify forms while achieving texture, rather than a ‘flat plane.’[xiv] Smith will later state, ‘Paint is something I’m never finished with because my concept is not wholly integrated or contradicted, whichever the case may be. Solid color is too easy and not my challenge.’[xv] In a new series of tall sculptures he calls ‘Sentinels,’ Smith introduces wheels and stainless steel finished with a mechanical grinder, which results in a textured, reflective surface. He also makes a number of reliefs, some of which contain animal bones, and casts them in bronze.

1957 – 58

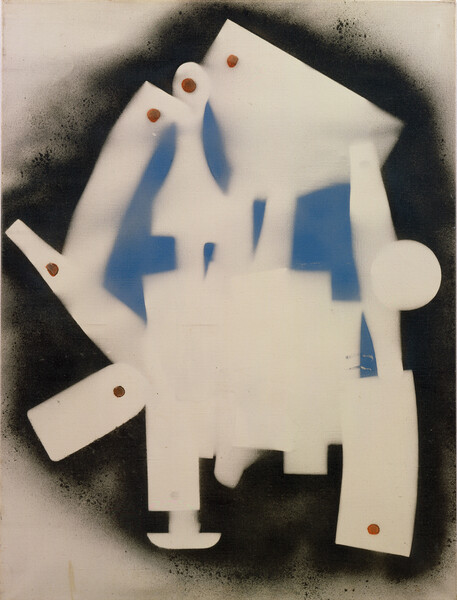

Smith expands upon certain formal ideas he explored in the Sentinels, such as incorporating overlapping planes of stainless steel, in works including ‘8 Planes 7 Bars’ (1957-58) and ‘25 Planes’ (1958). At 145 inches, ‘8 Planes 7 Bars’ measures nearly 3 ½ feet higher than Smith’s tallest sculpture to date. Smith begins laying down large sheets of canvas on his workshop floor, arranging objects on them ranging from scrap metal to organic refuse, spraying enamel paint from aerosol cans on and around the objects, then removing them from the surface, leaving behind silhouettes of varying shapes intertwined with vibrantly colored passages. This technique yields a body of paintings known as the ‘Sprays.’ Smith’s work is the subject of three exhibitions in New York City, including a retrospective at MoMA that features a selection of 34 sculptures made over the past two decades shown alongside paintings and works on paper. Hilton Kramer publishes a joint review of the exhibitions in ‘Arts Magazine’ in which he affirms Smith’s position as ‘an artist of international importance whose achievement must henceforth figure in any serious discussion of modern art.’[xvi]

David Smith, Untitled, 1958-59. Estate of David Smith, New York, NY

David Smith, 25 Planes, 1958. Courtesy National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

1959

A small selection of the Sprays are exhibited at Bennington College in Vermont. Smith visits New York City for the opening of ‘The Museum and Its Friends: Eighteen Living American Artists’, at the Whitney Museum, which includes four of his sculptures. He stays in the city to attend Barnett Newman’s first New York exhibition in eight years, held at the esteemed gallery French & Co., where Greenberg had recently been hired as an advisor for a new contemporary exhibition space designed by Tony Smith. The show features Newman’s paintings ‘Vir Heroicus Sublimis’ (The Museum of Modern Art) and ‘Cathedra’ (Stedelijk Museum), each of which measures approximately 8 by 18 feet. The number of exhibitions featuring Smith’s work has nearly doubled over the 1950s. His last exhibition of the decade is ‘David Smith: Paintings and Drawings,’ a presentation of 22 large Sprays and over 30 ink drawings held at French & Co.—the second monographic exhibition in the gallery’s new contemporary space. The exhibition draws enthusiastic reviews from Emily Genauer in the ‘New York Herald Tribune’ and Dore Ashton for the ‘The New York Times,’ who both note the radical nature of the paintings.

David Smith, Circle and Parts on Central Column, 1959. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Houston, TX

1960

Smith participates in 24 exhibitions throughout the United States. French & Co. shows 44 recent sculptures in a one-person exhibition. ‘Arts Magazine’ publishes a special issue on Smith. Hilton Kramer writes: ‘Smith is the only American sculptor who brings an ample and fecund oeuvre covering three decades to the history of modern sculpture—the only one, that is, whose work has made a permanent change in sculpture itself.’[xvii] ‘I belong with painters, in a sense,’ Smith says this year; ‘and all my early friends were painters because we all studied together. … And I never conceived of myself as anything other than a painter because my work came right through the raised surface, and color and objects applied to the surface. … Some of the greatest contributions of sculpture to the twentieth century are by painters.’[xviii]

Two workers inside the Italsider factory with David Smith’s Voltri series in progress, Voltri, Italy, 1962. Photo: David Smith

1962

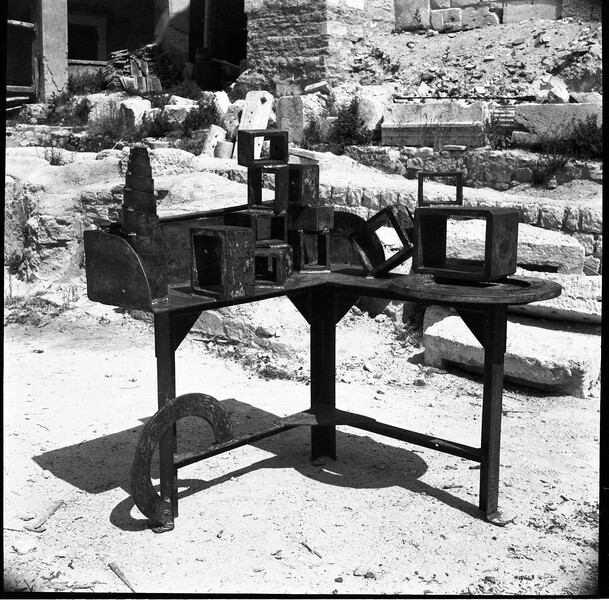

Smith agrees to participate in the Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto, Italy. He is asked to create two works and is provided with ample space at a defunct factory building owned by the steel manufacturing company, Italsider, in Genoa. In this environment, Smith enters an unprecedented span of productivity, creating 27 sculptures in 30 days by welding together discarded tools and other objects he finds around the factory site. After returning to New York, Smith tells art critic David Sylvester, ‘Italsider let me roam all the factories—pick out whatever I wanted—let me work without interruption…. I have never made so much—so good so easy in such condensed time as in my 30-day Italian phase.’ Smith names this series of work ‘Voltri,’ after the district in Genoa where the factory was located. Milan photographer Ugo Mulas documents the making of the Voltris and their installation in the amphitheater of Spoleto. Smith will expand on the series in Bolton Landing, making 25 numbered sculptures he calls ‘Voltri-Bolton’ or ‘Volton.’ Photographer Dan Budnik arrives in Bolton Landing and photographs Smith’s sculptures arranged in the fields. Smith makes ‘Windtotem’, which stands nearly 15 feet tall. He begins ‘Tower I’ (1962-63). Measuring 23 ½ feet high, this sculpture will become the tallest work of Smith’s career.

Voltri XVI (1962) installed in Spoleto, Italy, 1962. Photo: David Smith

David Smith, Untitled, 1963. Estate of David Smith, New York, NY

1963

Smith begins making paintings of female nudes using black enamel applied to canvas with a syringe. He makes a group of medium-sized Sprays on canvas in a range of formats and sizes that are based on arrangements of machine shop templates. He also makes a large number of smaller Sprays on paper featuring compositional arrangements that resemble his geometric sculptures and, unlike the Sprays on canvas, contain a horizon line indicating gravitational orientation. Budnik makes another visit to Bolton Landing and focuses on the Cubis. His photographs are published as a photo-essay in ‘Life’ magazine.[xx] Smith teaches at Bennington College.

1964

Smith makes his first ‘Wagon,’ one of three horizontal steel sculptures mounted on wheels that he either makes or buys from Bethlehem Steel Company. He also makes several ceramic pieces at Bennington Potters. They are shown at the American Federation of Arts Gallery in New York then travel throughout the country. On multiple occasions, Smith articulates the importance of size as it aligns with his stance against the commodification of art: ‘I build nothing for anybody to use, in any particular sense. I build as big as I can afford, and I build as good as I can think…. I have worked so long that I don’t belong to anybody.’[xxi] And: ‘I’m going to make [sculptures] so big that they can’t even be moved.’[xxii] Reflecting on Smith’s work, O’Hara says, ‘It’s the nature of sculpture to be there. If you don’t like it, you wish it would get out of the way, because it occupies space, which your body could occupy. ... In a sense, they are benign, because they offer themselves for your pleasure. But beneath that kindness is a warning: don’t be bored, don’t be lazy, don’t be trivial, and don’t be proud.’[xxiii]

David Smith, Cubi XXVII, 1965 © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Photo: David Heald

1965

‘Vogue’ magazine publishes an article on Smith by Motherwell_,_ with photographs by Irving Penn. Smith is appointed to the National Council of the Arts by President Lyndon B. Johnson. On 23 May, Smith dies from injuries sustained in a car accident near Bennington College. His funeral is held three days later near Bolton Landing, where eulogies are delivered by Motherwell, sculptor James Rosati, and Stanley Young, a representative of the National Council for the Arts. A memorial exhibition is held in the fall at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. MoMA’s International Council organizes a retrospective of 50 sculptures made between 1933 and 1965 that will travel through Europe the following year. – Explore our online exhibition ‘David Smith. Sprays’, including six virtual museum loans alongside significant works spanning from 1958 until 1964. Curated by the artist’s daughters and co-presidents of the David Smith Estate, Candida and Rebecca Smith, and Dr. Jennifer Field, Executive Director of the David Smith Estate, this exhibition provides an in-depth journey through this pioneering body of work.

[i] I would like to thank Tracee Ng, Researcher, Estate of David Smith, for allowing me access to the manuscript of her forthcoming chronology, to be published in the David Smith sculpture catalogue raisonné in 2021. Her thorough research has provided the basis of this chronology.[ii] David Smith, ‘Interview by Thomas B. Hess’ (1964) in Susan J. Cooke, ed., David Smith: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Interviews (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 380. Hess interview, Cooke, 380.[iii] David Smith, ‘Autobiographical Notes’ (1950), Cooke, 99.[iv] Trinkett Clark, The Drawings of David Smith (Washington, D.C.: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1985), 24.[v] David Smith, ‘Lecture, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture’ (1954), Cooke, 233.[vi] David Smith, ‘Events in a Life,’ in Cleve Gray, ed., David Smith by David Smith (New York, Chicago, San Francisco: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968), 25.[vii] Clement Greenberg, ’American Sculpture of Our Time: Group Show,’ The Nation (January 23, 1943). Quoted in Cooke, 107n15.[viii] Emily Genauer, ‘Art This Week,’ New York World-Telegram (January 5, 1946).[ix] David Smith, ‘Sketchbook Notes: He May Be Intuitive Enough to Make It; Nothing Put Down with Force and Conviction is Meaningless’ (1957), Cooke, 289.[x] David Smith, ‘Notes for Elaine de Kooning’ (1950), Cooke, 127.[xi] Ibid.[xii] David Smith, ‘Lecture, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture’ (1952), Cooke, 163.[xiii] David Smith, ‘Lecture, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture’ (1956), Cooke, 279.[xiv] David Smith to Herman Cherry, December 9, 1956. David Smith Archives, Estate of David Smith.[xv] David Smith to Clement Greenberg, March 31, 1964. Clement Greenberg papers, 1937-1983. Archives of American Art.[xvi] Hilton Kramer, ’Month in Review,’ Arts Magazine 32, no. 1 (October 1957), 48.[xvii] Hilton Kramer, ‘The Sculpture of David Smith,’ Arts Magazine 34, no. 5 (February 1960), 22.[xviii] David Smith, ‘Interview by David Sylvester,’ Cooke, 325.[xix] David Smith, ‘Interview by Frank O’Hara’ (1964), Cooke, 425.[xx] ‘David’s Steel Goliaths,’ Life 54, no. 14 (April 5, 1963), 129–33.[xxi] David Smith, ‘Interview by Marian Horosko’ (1964), Cooke, 415.[xxii] David Smith, ‘Interview by Thomas B. Hess’ (1964), Cooke, 387.[xxiii] Frank O’Hara in David Smith, ‘Interview by Frank O’Hara’ (1964), Cooke, 426-27.