Essays

The Making of Simone Leigh’s Brick House

by Meg Whiteford

Simone Leigh and her sculpture Brick House while in progress, 2018. Photo: Timothy Schenck

- 7 June 2020

- Essay courtesy the High Line

Simone Leigh’s sculpture, the inaugural High Line Plinth Commission, was first unveiled in June 2019 on New York City’s celebrated greenway. Brick House renegotiates the politicized and frequently-erased black female body as it relates to an urban North American landscape.

In these times of global crisis and isolation, with restrictions varying between cities and countries, some of us are unable to go on walks, view public art or engage with cultural spaces. Beyond these temporary limitations, public art embodies our sense of community and society, offering a semblance of normality and a reminder of life before lockdown. Read below on the inception and journey of the sculpture, from its dialogue with historical architecture in the US and Cameroon to the material processes that went into creating Brick House, introducing “a different idea of beauty” into the urban landscape.

Brick House, Simone Leigh’s commission for the inaugural High Line Plinth, is a monumental 16-foot-tall bronze bust of a Black woman whose skirt resembles a clay house. The sculpture is infused with the architectural concepts and processes taken from West Africa as well as the American South: the Batammaliba architecture from Benin and Togo, the Mousgoum people of Chad and Cameroon, and the restaurant Mammy’s Cupboard, in Natchez, Mississippi. Currently in the process of being fabricated in Philadelphia at Stratton Studio, Leigh designed and constructed this massive work through a complicated and fascinating multi-step process that pays homage to these ‘architectures of anatomy’. Batammaliba, the name of people of Northeast Togo, translates as ‘those who are the real architects of the earth.’ The Batammaliba believe in the interconnected relationship between architecture, humans, and their environment. The designs of each house, place of worship, and gathering space serve as visual reminders of the human body. Within this tribe, the architects are involved in all the steps it takes to erect a structure: from conception to design to fabrication.

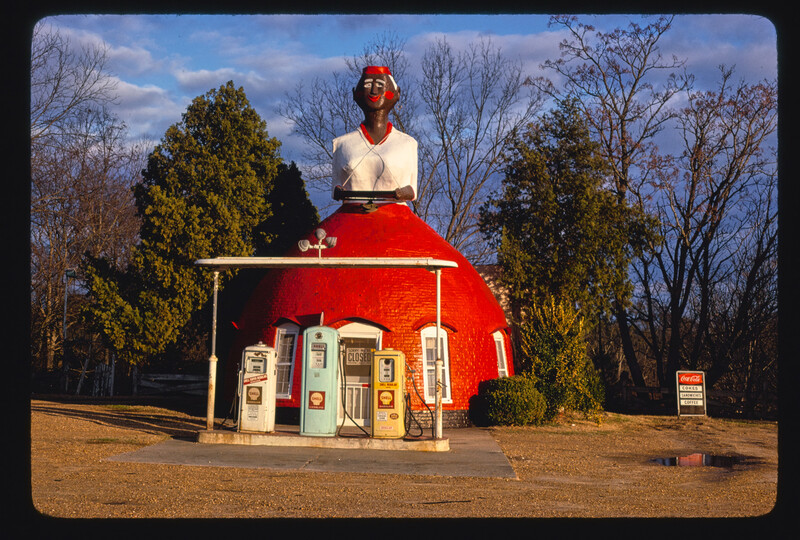

Mammy’s Cupboard, angle view, Route 61, Natchez, Mississippi, 1979. Courtesy John Margolies Roadside America photograph archive (1972-2008), Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Moussgoum obus / obi structures in Pouss, northern Cameroon near the border with Chad. Carsten ten Brink

Mammy’s Cupboard remains an embodiment of the Black woman’s form as symbol for the labor she provides. That metaphor of body as function, as informed by these intersecting cultural references, provides a point of entry for understanding Leigh’s Brick House.

Leigh was also inspired by Mammy’s Cupboard, another built structure that references the human form, though in a much more direct way. Built in 1940, Mammy’s Cupboard is a restaurant in Natchez, Mississippi. The brick restaurant is shaped like a 28-foot-tall woman wearing a round skirt that towers alongside US Highway 61. Mammy’s Cupboard originally took the guise of a darker-skinned Mammy figure, the racist archetype of a Black woman domestic worker that was prevalent in the late 19th to early 20th centuries and which was popularized in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and later with the character of Mammy in the film Gone with the Wind. Though repainted with a paler skin tone to downplay the resemblance to the racist stereotype, Mammy’s Cupboard remains an embodiment of the Black woman’s form as symbol for the labor she provides.

That metaphor of body as function, as informed by these intersecting cultural references, provides a point of entry for understanding Leigh’s Brick House. The sculpture began as a ceramic maquette in Leigh’s Brooklyn studio that was used to create digital 3D models of the sculpture for planning and visioning of the artwork on the Spur, and also as a reference for constructing the full-scale sculpture. Then, roughly two tons of modeling clay specially chosen from a French quarry (which is said to be the one where Auguste Rodin took his clay from) were mounted onto an armature and sculpted by the team, with Simone overseeing the shapes and textures of the different elements. Leigh and High Line Art chose the Stratton Foundry for their experience and expertise with hand-sculpting and casting in large-scale, bronze sculpture. Often when an artist wants to create a sculpture ambitious in size, a smaller maquette will be reproduced as a full-scale foam model from which the mold is made. However, Simone had concerns that a computer generated reproduction would lose the visible, personal touches important to her process.

Photo: Timothy Schenck

Simone Leigh with a wax mold of a braid for Brick House at Stratton Sculpture Studios. Photo: Constance Mensh

For example, vertical, elongated ridges running along the sculpture’s base reference the ridges of teleuks—the dome-shaped dwellings of the Mousgoum, which are made from a mixture of soil, grass, and animal dung. The surfaces of Brick House were textured with sponges and steel wool to draw resemblance to the texture of the teleuk. The ‘skirt’ of the piece can be read as the ‘walls’ of the house, or perhaps an upturned calabash bowl. And Brick House’s braids each end in cowries, a nod toward the Batammalibian priests’ sacred geomancy shells, amongst other allusions. As you see in this photo of an earlier maquette made for the 2017 exhibition of proposals for the Plinth, Leigh originally planned to sculpt rosettes for the sculpture’s hair. The stylized rose curls would have been made from porcelain, a medium that recurs throughout Leigh’s work. However, hand-making rosettes at a ‘Brick House’ scale proved too challenging, and too time-consuming. Leigh and the Stratton team then rethought the architecture of the sculpture to better fit its aesthetics and timeline. The rosette challenge resulted in a dynamic solution: Brick House would don a textured Afro with asymmetrical cornrow braids around the scalp. The work’s hanging braids were inspired by Thelma, the daughter on the 1970s television show Good Times.

Photo: Michelle Gustafson

Bronze pouring into the molds at Stratton Sculpture Studios. Photo: Timothy Schenck

“I thought: ‘What better place to put a Black female figure?... Not in defiance of the space, exactly, but to have a different idea of beauty there.‘”—Simone Leigh

Once the clay model was completed, the team then made a plaster mold fabricated in 100 separate pieces and wax positives were created from the plaster. Next, each of the wax casts was dipped as many as or more than 20 times each into a ceramic ‘slurry’ (a recipe of silica, or calcined clay, and a binder) that form the molds into which six thousand pounds of bronze (400lbs at a time) was poured. The bronze was melted into a crucible, a container for the materials to be processed at high temperatures. These bronze building blocks were then sand blasted, fitted, and welded together to form the completed Brick House. There is only one step remaining: transporting the massive work of art from Philadelphia to New York, where it will be craned onto the Spur on the High Line in April 2019. Once it arrives in New York City, Brick House will peer down upon passing traffic along 10th Ave. and 30th St. and tower above park visitors. This is an exciting moment for the High Line, the vistas of the West Side, and all of New York: sculptural architecture meets historical architecture with an undeniable, and highly visible example of Black female representation. “I thought: ‘What better place to put a Black female figure?’” says Simone Leigh, describing Brick House in the New York Times. “Not in defiance of the space, exactly, but to have a different idea of beauty there.”

Rendering of Simone Leigh, Brick House, 2018 – 2019. James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio and Renfro. Courtesy of the City of New York

Simone Leigh, Brick House, 2019 © Simone Leigh. Photo by Timothy Schenck

In New York City, there are a small handful of monuments depicting important African American figures in US history, including Frederick Douglass in Central Park, Louis Armstrong in North Corona, and Jackie Robinson in Upper Manhattan. Among them, only one is of an African American woman—Harriet Tubman in Harlem. This paucity reflects the general lack of representation of Black women, real or imaginary, in public sculpture in this city and elsewhere. This underrepresentation is compounded by the small number of permanent, public sculptures, (just four) figurative or abstract, created by Black women artists permanently on public view in New York. Surrounded by a competitive landscape of glass-and-steel towers shooting up from among older, industrial-era brick buildings, Simone Leigh’s magnificent sculpture will challenge visitors to think more critically about the architecture and aesthetics around them, and how they these structures reflect our customs, values, priorities, and society as a whole.

–

Simone Leigh’s Brick House will be view on The High Line, New York NY, through September 2020.