Essays

Excerpt from drag diary, a travel notebook in progress

By Jarrett Earnest

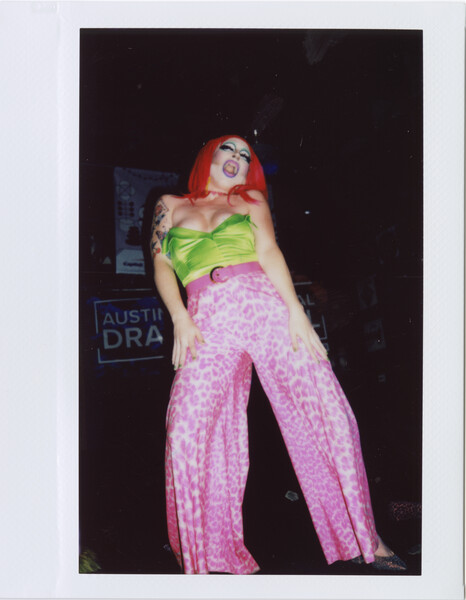

Brigitte Bandit (Austin) performing to Katy Perry’s cover of the Outfield’s “Your Love” at Valhalla. All images: Austin, Texas, November 2019. © Jarrett Earnest

- 17 March 2020

Thursday, November 14, Austin, Texas

The queen beside me is having a mild panic attack.

‘I feel like a kid on the first day of school; I don’t know anyone,’ she says in a slow Southern drawl to a willowy drag king beside her. We’re sitting back-to-back on taupe-colored benches deep in the bowels of the Holiday Inn Midtown, host to the Austin International Drag Festival, which, in its sixth year, describes itself as ‘the largest and most diverse drag festival in the world.’ I’m eavesdropping on this conversation just outside the Hill Country Ballroom, which will house the main stage for the next four days. Like most of the nonlocal artists, vendors and attendees, I’m checked in to the hotel for the duration. I came here hoping to figure out why drag matters so much now, to me personally and to the broader culture.

But she cuts him off: ‘Only from Instagram!’

‘Well, you know me,’ he continues, but the queen is not comforted.

Performers have been slotted into continuous five-minute spots for the next five hours, before the action all moves to downtown bars for the night. This aspirational timetable, with a lineup of talks, signings and workshops, is accessible via an app called Sched, which warns that the program can change at any moment, for any reason. At five in the afternoon, we’re already an hour behind, and the air is electric with nerves waiting for the kickoff.

‘You’ll feel better once you get to perform,’ the king says and walks away.

Lucy Stoole (Chicago) at Swan Dive

James Majesty (Los Angeles) performing to Slayyyter’s “Candy” at Swan Dive

With office-style ceiling tiles and fluorescent lights, the interior is a calculated rainbow of neutrals. Midlevel corporate hotels are specifically generic, locating you precisely no-place. We are in a Holiday Inn that could be anywhere in the country. Similarly, the ‘ballroom’ is designed to accommodate everything from bar mitzvahs to orthodontia conferences and can be sectioned off into smaller spaces with temporary partitions that retreat into the walls. I imagine that at this exact moment, in an identical room, preparations are being made for a sweet 16 party in the parallel universe of the Holiday Inn, East Windsor, New Jersey. Today, this ballroom’s wide rectangle is opened to its full expanse. At the center is a temporary stage, about a foot and a half off the ground, running against the back wall with a catwalk extending up the middle, making an elevated ‘T.’ Just inside the entrance is a folding table holding a sound board, laptop, monitors and a manual spotlight on a tripod.

Around the room’s perimeter run two rows of tables draped in black cloth with staffed displays for the ACLU; Planned Parenthood; the Kind Clinic, which offers free STD testing; Drag Out the Vote™,’ a ‘nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that works with drag performers to promote participation in democracy’; Imperfect Foods, a delivery service on a mission to reduce food waste by shipping odd-shaped produce direct to consumers; a drag-themed cruise ship that travels from Los Angeles to the ‘Mexican Riviera.’ Interspersed amid these tables are merchants selling handmade wares, like panties covered with the faces of the Golden Girls, paintings of oversized lips on canvas, as well as every implement imaginable for the drag trade—multicolored wigs, adhesive facial-hair pieces, rhinestoned accessories, extra-large spiked heels.

Ursula Major and One Million Moths (Salt Lake City) at the Holiday Inn Midtown Austin

On a table near the entrance are stacks of free stickers: ‘my pronouns are: she/her,’ ‘my pronouns are: he/him,’ ‘my pronouns are: they/them.’ The stickers continue with ‘xe/xem’ and ‘ze/zir’ and ‘my pronouns are _______’ and, for those who see stickers as a conversation starter, ‘ask me about my pronouns.’ Posted around the room are signs proclaiming a ‘drama free zone’ and that ‘drag is not consent,’ explaining that individuals who don’t want to be photographed or touched can flag themselves with colored stickers.

The first day is dedicated exclusively to ‘male drag,’ known as KingFest. Papi Churro, an Austin-based king dressed as Mugatu, the fashion-designer villain from the 2001 movie ‘Zoolander,’ emerges to emcee. Fifty kings are slated to go on that afternoon, making up about half the audience, which sits on the floor around the stage or stands along the edges of the room. Churro reminds us to cheer and to tip and that ‘consent isn’t only sexy—it’s what? Mandatory!’ Further announcements are made—that this is a ‘positive’ environment and that daytime shows are to hover between PG and PG-13. I drove all the way from New York to Texas for the irreverent antagonism of drag queens and somehow found myself at Bible camp?

‘About 15 of us squeeze into one of the vans, which contains a strong first-day-of school vibe: a bunch of positively disposed strangers, about half in drag, trying to sort out a provisional social order as swiftly as possible against a backdrop of widespread national chaos.’

As I’m having this thought, a drag king from Bloomington, Indiana, named Corvin Rose walks on stage in a loose white blazer over a T-shirt and slacks and announces, ‘This number is about religion and being LGBTQ.’ A plaintive pop-gospel piano begins to bounce and an emotional female vocal begins: ‘Well, you almost had me fooled / Told me that I was nothing without you / Oh, but after everything you’ve done / I can thank you for how strong I have become.’ Out of a Bible, Rose unfurls a paper banner reading ‘love?’ and then on the lyric ‘I’m proud of who I am,’ a folded image of a rainbow. Rose then walks to the end of the stage toward a stool holding seven small cups. As the chorus peals into ‘I hope you’re somewhere prayin’, prayin’ / I hope your soul is changin’, changin’,’ Rose’s jacket comes off and the cups are poured, one by one, revealing their contents to be water mixed with food coloring, which makes a pale, runny rainbow down the front of Rose’s white T-shirt. With a chin-length bob and soft, smoky eyes, Corvin Rose looks less like someone going for a ‘male’ illusion than for a hot dyke preacher, lip-sync punctuated with ecclesiastical hand gestures. The song Rose has chosen, ‘Praying,’ by Kesha, is widely regarded as a salvo in the singer’s ongoing legal battles with the producer Dr. Luke—someone she has accused of sexual and emotional abuse. This narrative backdrop is palpable in Rose’s interpretation, even as the role of abuser is recast as modern Christianity.

Kat Sass (Chicago) performing to Ursine Vulpine’s cover of Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game” at Swan Dive

Diana Fire (Portland, Oregon) performing to Hailee Steinfeld’s “Starving” at Swan Dive

I grew up Pentecostal, going to evangelical churches and prayer meetings. I remember how often pop music would be appropriated for services, probably because of the way in which great pop songs tap so effortlessly into preexisting emotional architecture. As a 10-year-old member of the puppet team of the First Assembly of God in Arcadia, Florida, I made colorful felt hand puppets sing along with Johnny Nash’s feel-good 1972 radio hit ‘I Can See Clearly Now.’ At around 13, I was on the worship team of Rowan Christian Assembly in Salisbury, North Carolina. In front of the entire congregation we performed a multi-person interpretive dance that consisted of alternating between making ‘X’ and cross shapes with perpendicular dowel rods held in each hand, moving in group formation to Bonnie Tyler’s barn-burner ‘Total Eclipse of the Heart.’ The moves had been choreographed by a middle-aged woman with bright red hair who often wore a purple crushed-velvet dress. The pop-opera’s lyrics about romantic obsession transposed themselves seamlessly into being about the love of Christ. Looking back, despite the explicit homophobia of the Christian Right, I count the performance as one of my first experiences of both the sacred feminine and unadulterated faggotry. Like Corvin Rose’s rendition of ‘Praying,’ Tyler’s—‘I don’t know what to do and I’m always in the dark / We’re living in a powder keg and giving off sparks’—was, in my young heart, devoid of even the most remote irony.

At KingFest, other performances include Texan Hunsen Abequeer (a play on the demon-king Hunson Abadeer from the animated series ‘Adventure Time’), dressed in a sweater vest and bowtie, standing in a waist-high killer-plant rig, singing a live rendition of ‘Grow for Me’ from the musical ‘Little Shop of Horrors;’ the Elton J’s, a supergroup of five drag kings from across North America done up in different Elton John looks, vamping to a choreographed medley that includes ‘Can You Feel the Love Tonight,’ ‘The Bitch Is Back’ and ‘I’m Still Standing’; Damien D’Luxe from Minneapolis, dressed like an anatomically correct Sonic the Hedgehog, clowning to Queen’s ‘Don’t Stop Me Now,’ playing off the character’s speed, yes, but also the line ‘I wanna make a supersonic man out of you.’ (D’Luxe’s bulging Sonic crotch reminds that the hedgehog is also a cult sex symbol in a subgenre of cartoon hentai porn); and lastly, from the local troupe Boiz of Austin, Alexander the Great enacting a slow-motion striptease, shedding a silver lamé spacesuit while floating horizontally around a portable stripper pole to the Police’s ‘Walking on the Moon,’ which brings to mind a butch version of the opening credits of ‘Barbarella.’ In these somewhat arbitrary examples alone are references to cartoons, musical theater, celebrity impersonation (of a flamboyant gay man), cosplay, burlesque, science fiction and classical antiquity, with musical references spanning more than 50 years of popular culture—not to mention all of this incredible complexity occurring under the rubric of ‘masculinity.’

The shows in the ballroom end around 9 p.m. and cargo vans with AIDF written on the sides in pink chalk start shuttling guests to venues in the Red River Cultural District downtown. About 15 of us squeeze into one of the vans, which contains a strong first-day-of-school vibe: a bunch of positively disposed strangers, about half in drag, trying to sort out a provisional social order as swiftly as possible against a backdrop of widespread national chaos. The K-pop party—hosted by Soju, a YouTube-famous Chicago queen who was eliminated first on season 11 of RuPaul’s ‘Drag Race’—is held at the nightclub Elysium. Across the street at Valhalla is the trans and nonbinary showcase. The space is narrow, dingy and intimate. Jack Rabid, another member of Boiz of Austin, who self-describes as a drag king, cos player and David Bowie impersonator, introduces the night, explaining how special it is for ‘the Fest’ to highlight not only kings but also nonbinary performers, who often feel minimized within the world of high-femme drag queens. Clad in a glittering skin-tight wine-colored gown, fur stole, false lashes, fake mustache, oversized sparkling earrings and a black top hat, Rabid kicks off the evening around 11 p.m., lip-syncing to ‘Never Tear Us Apart’ by INXS. Watching and listening, I think about how the incredible proliferation of drag in recent years has been propelled by the seismic shifts within our society’s conversations around gender identity and sexuality; one of the most basic definitions of ‘drag’ is playing within the unstable matrix of gender, which makes a showcase like this a perfect cross section of the ways trans and nonbinary people are inventing themselves and our world.

‘[There] is no longer really ‘subculture’ in the traditional sense, but something more like overlapping rings of signification, legible to varying degrees from community to community. A drag festival turns out to be one of the most comprehensive ways for people to make sense of these new cultural formations.’

Ricky Rosé, a drag king from Washington, D.C., walks out next in a white robe emblazoned with a silver-sequin crucifix across the chest, accessorized with a dark red velvet cloak, a painted black chinstrap beard, thick glasses and a plastic gold crown. They are followed by an attendant wearing a matching cloak, holding a red velvet skull in one hand and a burning crimson candle in the other. Halsey’s darkly overwrought ‘Castle’ starts playing, complete with its samples of Agnus Dei: ‘I’m headed straight for the castle / They wanna make me their queen / and there’s an old man sitting on the throne / That’s saying I probably shouldn’t be so mean.’ Rosé gives the song a burlesque treatment: Under their robes are black fishnets, red lingerie and a red corset hiding sparkling sacred-heart pasties. By the end, the attendant has splashed red wax from the candle across Ricky’s chest—you know, just some simulated sex and casual sacrilege, and in four and a half minutes it’s over. As counterpoint, the Bearded Queer, a self-proclaimed ‘Conceptual Shit Artist’ from Denton, Texas, comes next, prancing around the stage in occult horror drag—curling ram’s horns, spiked epaulets and ripped tights—to Depeche Mode’s sardonic ‘Personal Jesus.’

Symone N. O’Bishop (Columbia, South Carolina) performing to a mashup of Dondria’s “You’re the One” and Todrick Hall’s “Nobody” at Valhalla

The night continues with back-to-back numbers by the Haus of Kikii from Dallas. Face painted equal parts Kabuki and Richard Linder, Kilo Kikii moves like an angular marionette to a mashup of Lady Gaga’s ‘Bad Kids’ and ‘Applause’ and Slayyyter’s ‘Motorcycle.’ Their drag ‘daughter,’ Opulent Dekay, wears a black crop top with a fuzzy heart across the chest that says ‘Sex Toy.’ Dekay’s oval face is contoured with doll-like makeup, shading their already thin nose to a knife’s point. Perched on pink platform stilettos, a straight silver wig accentuates their already exaggerated tallness and thinness. A thematic mix plays, combining ‘I Am Not a Robot’ by Marina and the Diamonds and ‘Make Me a Robot’ by Tessa Violet, capped off by ‘Still Alive,’ the ironic congratulatory song from the end of the video game ‘Portal,’ sung in the voice of a robot antagonist: ‘I’m not even angry / I am being so sincere right now / Even though you broke my heart / and killed me.’ All three tracks have the same exaggerated sing-song phrasing and flat affect, allowing Dekay, tottering around the stage, to evoke the mechanical Olympia doll from Offenbach’s opera ‘Tales of Hoffmann.’

There is no longer a meaningful high/low distinction within our culture. One effect of the internet and social media has been a leveling of cultural reference and association, as if everything that ever existed rests on a single horizon, imminently accessible. The result is no longer really ‘subculture’ in the traditional sense, but something more like overlapping rings of signification, legible to varying degrees from community to community. A drag festival turns out to be one of the most comprehensive ways for people to make sense of these new cultural formations.

Anhedonia Delight (Cleveland) as Divine in Pink Flamingos at the North Door, November 2019

Ricky Rosé (Washington D.C.) performing to Halsey’s ‘Castle’ at Valhalla

There are 33 performances over the course of the three-hour-long trans showcase. Symone N. O’ Bishop, a queen from Columbia, South Carolina, lip-syncs Dondria’s ‘You’re the One’ in a magenta pixie-cut wig that matches her hot-pink homage to a Donna Reed gown. Her tagline—‘I’m not a snob, I’m just painted that way’—is a riff on the high-camp cartoon bombshell Jessica Rabbit, who famously cooed, ‘I’m not bad, I’m just drawn that way.’ After taking off the chiffon skirt and jacket and revealing a ruffled salsa-inflected miniskirt with pastel rainbow trim and a cropped blouse with full sleeves, SNOB finishes with ‘Nobody’ by Todrick Hall. Fluid Snow, a trans nonbinary drag king from Tel Aviv, follows in a fedora and painted goatee, wearing a tailored suit made from fabric printed with Nagel-like illustrations of women. Over the course of James Brown’s ‘It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World,’ Snow removes jacket and shirt to reveal a bound chest, a common practice among drag kings and trans men, to minimize the bust line. The word ‘king’ is written on this one in marker. Snow pushes the lyrics of the song into unexplored territory after removing the binding to reveal a bare chest and evidence of top surgery: ‘This is a man’s world / This is a man’s world / But it wouldn’t be nothing, nothing, without a woman or a girl.’

By 2 a.m. I am waiting with a crowd on the street corner in front of Valhalla for the summer-camp vans to take us back to the Holiday Inn. One van is mobbed and leaves full, promising to return in half an hour. I get into the next one with the Haus of Kikii girls, talking to ShelbyAnn Waylon-Kikii 2.0, who is getting her PhD in library science from the University of Texas in Dallas. We talk about her interest in archival research, and I think about the depth of drag’s scholarly impulse toward a history of taste, an archaeology of pop culture. So much of the pleasure in the scene resides in the specificity of the references and associations, as well as in the nuances of the execution. Drag gets really good not merely with a flawless illusion or allusion, but when each aspect—a look, a dress, a song, a gesture—amplifies the others to create nuance and to undermine, re-contextualizing all of their meanings in real time.

Outside the hotel, clusters of people in various states of undress smoke and talk. The late-night fluorescent corridors are empty save for those of us in town for the fest, and the contrast between us and the decor—chance juxtapositions of glitter and beige—simmers with a David Lynch style of American surrealism.

– Jarrett Earnest, based in New York, is an artist, writer and oral historian. His book ‘What It Means to Write About Art: Interviews With Art Critics’ was published in 2018. Last year, he curated ‘Closer as Love: Genesis Breyer P-Orridge: Polaroids 1993–2007’ at Nina Johnson gallery in Miami and ‘The Young and Evil’ at David Zwirner in New York. Companion books for both shows, from Matte Editions and David Zwirner Books, were recently published.