Conversations

Six decades in the art world: Calvin Tomkins sits down with Randy Kennedy

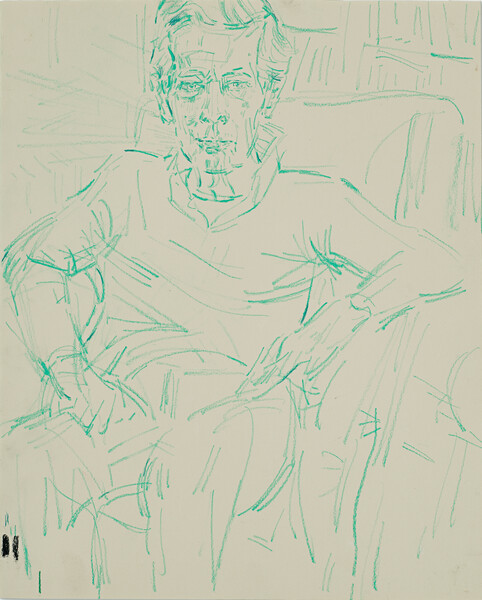

Elizabeth Peyton, Tad, New York, December 2019, 2020

In Eugene O’Neill’s unfinished play ‘The Calms of Capricorn,’ the protagonist Ethan Harford, second mate aboard a clipper bound for California, is admonished for easing sail during the ship’s attempt at a speed record. When fate presents itself, the captain tells him, one’s only duty must be ‘to follow one’s luck.’

Perhaps no American cultural writer over the last half century has had a more remarkable talent for following his luck than Calvin Tomkins. And in a life of letters approaching its 70th year, he has also been the beneficiary of an outsize portion of that luck. As a young foreign-news writer at ‘Newsweek’ in the late 1950s, he was dispatched at random one afternoon to the King Cole Bar at the St. Regis Hotel to interview an artist whose name registered only faintly—Marcel Duchamp, a meeting that would set the course of Tomkins’ career as one of the most admired art writers of his generation.

Earlier, he had become an accidental neighbor of Gerald and Sara Murphy, the storied Lost Generation couple whose friendships with Picasso, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Cole Porter and Natalia Goncharova would form Tomkins’ classic 1971 biography of the Murphys, ‘Living Well Is the Best Revenge,’ and ground his writings in the very foundations of Modernism. Even his choice of subjects for ‘The New Yorker’ over the decades—Rauschenberg, Cage, O’Keeffe, Bearden, Serra, Sherman, Hammons—began with an auspicious break.

In 1960, as a kind of tryout for the magazine, he had proposed a profile of a now little-known New Zealand painter and sculptor named Len Lye, when a new acquaintance—Billy Klüver, the pioneering Bell Labs engineer turned art impresario—warned him off. ‘Listen, you don’t want to write about that guy,’ Klüver said. ‘You want to write about Jean Tinguely.’ And thus Tomkins’ New Yorker career began with a literal bang—a piece about the infamous self-destruction of Tinguely’s ‘Homage to New York’ in the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art.

Calvin Tomkins and Christo at Running Fence, 1976, California. Photo: Gianfranco Gorgoni

Over a lifetime of historicizing others—in his pieces and his masterly biographies of Duchamp and Rauschenberg—Tomkins has long resisted submitting to the treatment himself. But in recent years he has been softening slightly to enshrinement. He donated his papers to the Museum of Modern Art and his art-book archive to the Redwood Library and Athenaeum in Newport, Rhode Island. On the occasion of the publication of his collected ‘New Yorker’ profiles, a six-volume boxed Phaidon set, ‘The Lives of Artists,’ Tomkins agreed to sit down for a series of interviews that began in the summer of 2018 and continued through this January, in Newport—where he and his wife, the ‘Vogue’ writer and curator Dodie Kazanjian, have a house; at their modest apartment on the Upper East Side; and at their favorite diner, Nectar, around the corner from the Metropolitan Museum. Last December, Tomkins, widely known in the art world by his nickname, Tad, turned 94, and this year marks his 60th on the staff of ‘The New Yorker.’ At our last interview, he was preparing to fly to Europe to work on his latest profile. These are edited and condensed portions of our conversations.

Randy Kennedy: Maybe we could start by talking about your earliest writing, even before you started working for ‘Newsweek.’

Calvin Tomkins: Well, it’s a little odd because the first thing I ever published was a novel. My father, who was a remarkable man, a businessman, knew how badly I wanted to be a writer. At that point, I hadn’t really taken hold of anything else in my life. So he staked me to one year of trying to write.

RK: You were just out of college?

CT: Yes. I’d gotten married very young. Before that, I’d been two years in the Navy and came back and accelerated the last three years at Princeton, so I was about 21 or 22. A family friend who lived in Santa Fe said it would be a good place to write. So we went there and found a little place—more than a cabin but less than a house—up in the mountains.

RK: What was the story about?

CT: It was quite autobiographical, about me and my older brother, Fred, going on a ski trip to Canada. That became the basis of what was to become the novel ‘Intermission.’ We moved into a house right in town. I had a little room over the garage and wrote there. Then we decided to go to Mexico and ended up in a place outside of Guadalajara, at a pretty little inn by Lake Chapala, which is huge, as big as Lake Champlain. We were there three or four months, and I wrote there, too. It was a kind of Hemingway-esque experience for me. I remember finishing the manuscript there and sending it to my agent. I heard back a few weeks later that it had been accepted by Viking Press! And then I had a vivid experience. There was no telephone where we were, so I sent a telegram to my parents back in New Jersey, something like, ‘Have turned pro. Viking accepts novel.’ My mother told me later that she had been on the phone when Western Union called—in those days you could have telegrams read to you over the phone. She wanted to tell my father right away and ran downstairs to find him. She found him listening on the back telephone in the kitchen, weeping. She’d never seen any kind of emotion like that from him. He was so happy. Of course, she told me that in strict confidence later.

RK: Do you think he had wanted to be a writer himself?

CT: I’m sure he did. But he ran a business, a building-materials business. The factory was in Newark. He had inherited it from his father, but it had been almost bankrupt when he took it over. He realized he had to take it in hand because a lot of people were dependent on it. I don’t think he would have chosen to do that if he’d had a choice. He used to say something that was supposed to have come from Samuel Johnson, when a widow complained to him that her husband had left her his printing business to run: ‘Do not worry, madame, for if business were difficult, those who do it could not.’ My father did it for about 40 years and made a success of it, a modest success. He was a man who read all the time and had a rather substantial library. He would have loved to be a writer, but the idea of me being a writer was something that really pleased him.

RK: Your family has been in the New York area for many generations, right?

CT: From at least the late 18th century. There’s a place up the Hudson, CT Cove—I lived there briefly with my first wife—that was founded by my great, great, great grandfather, who transported limestone and other materials down the river on barges. He eventually had a string of barges, and Cornelius Vanderbilt became his main rival on the river. They were doing the same thing, and family legend has it that, one day, Commodore Vanderbilt came to my grandfather and said, ‘I’m investing in this new thing called railroads. Why don’t you do it with me?’ And Great, Great, Great Grandfather said, ‘There’s no money in railroads! I’m sticking to the river.’

RK: Wrong choice.

CT: I’d say. Then on my mother’s side, I have pretty deep Southern roots. Her father, John Temple Graves, was a Hearst newspaper editor who was the nominee for vice president on the Independence Party ticket in 1908. He was also a hard-line segregationist and racist. In ‘The Mind of the South,’ W.J. Cash’s great book, Cash blames some of his rhetoric for helping to ignite the race riot in Atlanta in 1906.

RK: Good lord. Did you know him?

CT: No, he died the year I was born.

RK: Were there other literary people in your family? Or anyone connected to art?

CT: Not to speak of. My father had a small collection, some American Modernism—a Burchfield, a few things like that—and I remember he had a painting by Dufy. As far as literary, maybe the closest I got was an uncle who did nothing but read—my father’s older brother, also named Calvin. He actually never did anything. He was of that generation where I guess you could just do nothing. He was the only person I’ve ever heard of who read all 12 volumes of Toynbee’s ‘A Study of History,’ which is probably not an advisable thing to do. [Laughs]

RK: Do you remember the response to your novel?

CT: I remember mostly what my Aunt Kaps, my father’s sister, said. She, too, was a voracious reader. My book had the great misfortune, I guess you’d call it, of coming out the same season as ‘The Catcher in the Rye,’ about a month apart in 1951, and she said, ‘Well, I certainly am glad I’m related to you and not that J.D. Salinger!’

‘I must say, ‘Tender Is the Night’ was probably the most intense reading experience I’d ever had....I kept thinking about it. I couldn’t stop thinking about it….I wanted to be Dick Diver.’

RK: Who were your first literary heroes when you were young?

CT: Oh, the usual boy books—Jack London, ‘Tarzan of the Apes;’ ‘Lad, a Dog.’ I don’t think I had any particular advanced reading talents until I got to college. But I was probably drawn to writing early on because I had a very serious stutter, the kind in which you didn’t repeat syllables but just got stuck on a sound and couldn’t say anything at all. It was very upsetting in school. So I’m sure that writing, the whole act of writing, of not having to speak to express myself, felt like some sort of a victory over that or a way around it.

RK: What was the first piece of what real literature that just grabbed you by the neck?

CT: I’d say it was Hemingway and Fitzgerald. I took a course in modern American lit—Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, Sherwood Anderson. I remember being terrifically stirred by the language of early American modernism. And this was one my first great pieces of luck. In that house in Santa Fe one day, I’d been leafing idly through the library and pulled out ‘Tender Is the Night.’ I’d read Gatsby and the stories in college, but I must say ‘Tender Is the Night’ was probably the most intense reading experience I’d ever had. I became really involved in the story and the life and the character of Dick Diver. I kept thinking about it. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. It was very upsetting. I wanted to be Dick Diver. And then a couple of years later, we came back to New York and moved into a house in Snedens Landing, on the Palisades, and ended up right next door to Gerald and Sara Murphy, who I found out were the basis of Dick and Nicole Diver in the book. Our daughter wandered into their yard one day and we met, and when I made the connection to Fitzgerald, it was just amazing to me, like a fairy tale.

RK: Was Fitzgerald’s a writing style you wanted to emulate?

CT: It was more Hemingway, actually. There was an idolization of the life and the work—the novels, but mostly the short stories. There’s something really tangible about them. You believe them. And I guess I would say the opposite about Fitzgerald. Even ‘Gatsby,’ when I re-read it six or seven years ago, seemed badly written and clumsy. And I thought it was such a perfect novel at the time I first read it.

RK: Did you work on another novel?

CT: Yes, I came back from Mexico and immediately began trying to write another one. But I had this mistaken idea that with a first novel you could use personal experience, and then after that you had to make it all up. So I would make up one long complicated scenario after another, with a whole bunch of characters, and I’d get bogged down in plot. And then I’d realize it was just sort of fizzling out, nothing was really happening. I did get a few short stories published in magazines. And later I contributed short stories and humor pieces, what were called ‘casuals,’ to ‘The New Yorker.’ The magazine had been very much a part of my reading from early on. I was, in fact, born the same year as ‘The New Yorker,’ 1925.

RK: Wow.

Julia Child and Tomkins, c. 1974. Photo: Judy Tomkins

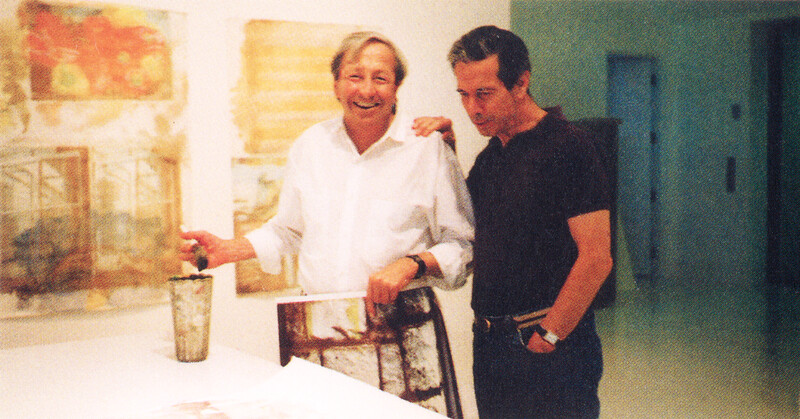

Robert Rauschenberg and Tomkins in the artist’s studio, c. 1997, Captiva Island, Florida. Photo: Dodie Kazanjian

Tomkins in his home office, 2011. Photo: Chester Higgins

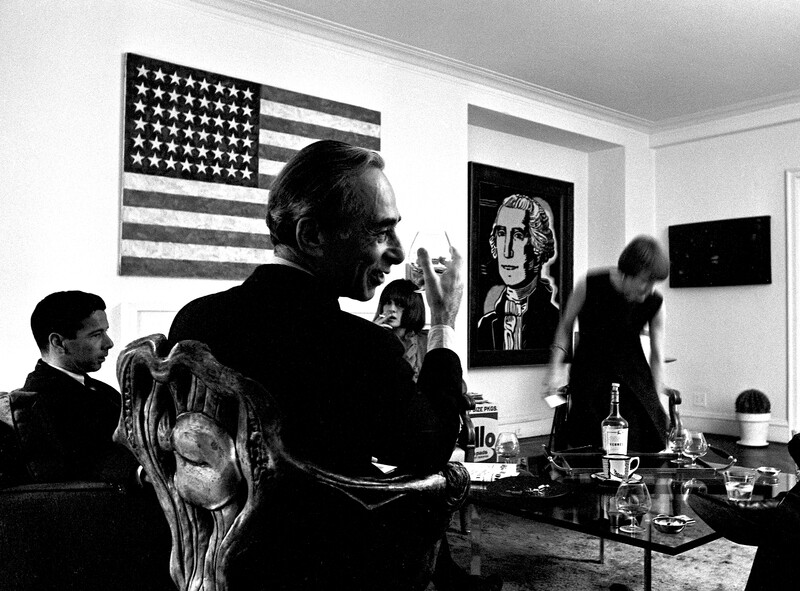

Tomkins and Leo Castelli, New York, 1964, Photo: © Ugo Mulas Heirs. Courtesy Archivio Ugo Mulas

CT: But at that time, in my mid-20s, my money from my father was running out, and the novel was not making money, so I had to start looking for ways to make a living. I worked for a while for Radio Free Europe, then got a job at ‘Newsweek,’ in foreign news, writing four or five stories a week at first and then doing longer ones. Correspondents from Europe would send in reams of copy, and the writers would use that as one of the sources for the story. The old timers who would write the main news stories were, in general, terrible writers. But there were some guys who wrote well, and I really learned how to do it at that job. After three years or so, I was promoted to editor in the back of the book—which was things like medicine, religion, movies. But not art! We didn’t have an art section. ‘Time’ didn’t either.

RK: So when you got the call to interview Duchamp, it wasn’t because you were known for knowing anything about art?

CT: Not at all. When they thought they needed to do a piece on art, they called somebody from another section. And I just got the call one day, out of the blue. Pure accident. It might have been from Kermit Lansner, a great editor there whose wife, Fay, was a very good painter. Kermit might have thought I had some aptitude for art, but I’d never written a single art piece. The first monograph on Duchamp, by Robert Lebel, had just come out in English, and somebody there must have thought it was newsworthy. Duchamp hadn’t made art for so long at that point that he had come to seem like a historical figure. But of course he was living right among us in New York.

RK: Were you someone who went to see art in those days, a museumgoer?

CT: This might sound unbelievable now, but I had almost no interest at all. Then, I don’t know quite how it happened, but Lansner got me interested in what was going on in contemporary art. He made me think there was something exciting going on. And I began going to the Museum of Modern Art at lunch hour, just by myself. And then later I started going there quite often.

RK: A lot has been written, by you and others, about that fateful first Duchamp meeting, but I’d love for you to tell me about it again.

‘I was called and told to go and interview Marcel Duchamp’—Calvin Tomkins CT: I had some very vague idea who he was. I knew about the Armory Show and ‘Nude Descending a Staircase,’ but I really didn’t know beans about him. I got the assignment and was told it was going to be the same day, that afternoon. I got an early copy of the monograph and had about 45 minutes to look at it. I just glanced at it and met him in the King Cole Bar, with that great Maxfield Parrish mural over us. The interview was set up there by Newsweek. When I arrived, he was already there ahead of me, sitting at a small table, and the thing I remember most vividly is that I asked a lot of dumb questions, and he managed somehow to turn them all around into something interesting. One of the few things I thought I knew about him was that he had retired, though of course we now know that wasn’t true; he was making ‘Étant donnés’ in secret in his studio. I asked him, ‘Since you’ve stopped making art, how do you spend your time now?’ And he said, ‘Oh, I’m a breather. A ‘respirateur.’ And I enjoy it very much.’ A couple of years later, Time Life asked me to do a small book on him—they were making a Time Life ‘Library of Art’ series and wanted Duchamp. I’ll never forget the first meeting. I went to the Time Life offices and there were about eight or nine people sitting around a table. A question came up that I didn’t know the answer to, and I said, ‘Well, I’m seeing Marcel in a couple of days, so I’ll ask him.’ Deafening silence. I looked around and realized everybody thought he was dead. Everyone in the room.

‘When I arrived, [Duchamp] was already there ahead of me, sitting at a small table, and the thing I remember most vividly is that I asked a lot of dumb questions, and he managed somehow to turn them all around into something interesting.’

RK: They might not have picked him if they thought he was alive.

CT: I don’t think they would have. After that first interview, I’d said to myself as a young journalist, ‘Wow, this is something.’ Because usually you have to pull all sorts of stuff out of people and try to make it interesting, but here he was doing it for me. He had this completely at-ease-with-himself demeanor. He’s what the French call at home in his own skin. And that put me at ease. I usually was very tense in an interview, but he made me feel totally comfortable.

RK: And it wasn’t long after this that the ‘New Yorker’ job came along?

CT: It was the next year. Roger Angell was the one who urged me to write for the magazine; he was a fiction editor there. He also lived in Snedens Landing, and he said, ‘Since you like the magazine so much, you should submit something.’ I started writing short humor pieces and sending them to Roger, who accepted some of them and rejected others. But I really wanted to be on the staff, so I finally went in to see William Shawn, the editor in chief. Shawn said, ‘We really like your humor pieces, but you can’t get along here on just that. You’d have to be able to write longer pieces, too. Do you think you could try something for us?’

RK: And that became the piece about Tinguely that ran in 1962?

CT: Well, by the skin of my teeth. A good friend of mine, Alastair Reid, the poet, who was around ‘The New Yorker’ a lot in those days, knew the artist Len Lye, who was from New Zealand and living in New York, making paintings and also kinetic sculpture, which was a hot new thing in those days. I was about to approach Lye, but someone suggested I go meet Billy Klüver at Bell Labs, who had been working with kinetic sculptors. And he put me on to Tinguely, who he said was a far better subject. Of course, I’d never heard of him.

RK: Did you know at that point that the art world was going to be your calling?

CT: Not in the early years. After that Tinguely piece, the next one was on dyslexia and children, the whole idea of speech and reading disabilities, which was something personal for me. And then I did a piece on John R. Pierce, who was a pioneering engineer at Bell Labs, and next, I think, a piece on the chancellor of the CUNY system. I was a real generalist and continued to write on subjects other than art. But Tinguely ended up being the art catalyst, because when I started working on him, a lot of people said,‘Well, you have to talk to Bob Rauschenberg,’ because he and Tinguely were close. So I did, and knew immediately that I had to write about Bob. And then Bob, of course, led to John Cage, and Cage very much led back to Duchamp. Cage was the primary carrier of the torch for Duchamp in this country. He’s the one who really helped to renew his reputation here. Rauschenberg opened up the whole art scene to me, and it began to seem like something nobody was writing about.

‘A lot of people said, ‘Well, you have to talk to Bob Rauschenberg,’ because he and Tinguely were close. So I did, and knew immediately that I had to write about Bob. And then Bob, of course, led to John Cage, and Cage very much led back to Duchamp.’

RK: I know from spending a lot of time looking through the archives at ‘The New York Times’ when I was there that the paper was indifferent at best, and often outright hostile, to most of the new art being made in those years.

CT: ‘The Times’ was doing very little, and John Canaday, the critic, was not much interested in this crowd. Neither was Hilton Kramer, later.

RK: Did Shawn or people at ‘The New Yorker’ have to be persuaded that these upstarts—apostates, I’m sure a lot of people thought—were interesting artists?

CT: Not at all. That was one of the things about Shawn. He was amazingly open to the new. A little later in my career, he was the one who suggested to me that I might like to do something about Robert Wilson, and I’d never heard of Wilson. I did have one editor there, a woman who’d been on staff for a long time, say to me after my John Cage profile came out, ‘You know, I’ve been trying for years to keep Cage out of the magazine.’ Cage was a special case. A lot of people just didn’t understand what he was doing.

RK: Was Shawn himself up on avant-garde performance and music?

CT: My guess is that he knew a little because of Wally, his son. I myself had started to form a kind of idea about new art being made after reading Roger Shattuck’s The Banquet Years,’ which was about the birth of the 20th century avant-garde in France through portraits of Apollinaire, Alfred Jarry, Erik Satie and Henri Rousseau. That’s what gave me the idea that I knew artists who could make up a book somewhat similar to that. [Tomkins’ ‘The Bride and the Bachelors,’ first published in 1965, told the interlocking stories of Duchamp, Rauschenberg, Tinguely and Cage. Merce Cunningham and Jasper Johns were added in later editions.]

RK: Do you remember having a sense that this scene, the post-Ab-Ex revolution, was truly important, historically, in the same league as the birth of the French avant-garde?

CT: I would like to say that I did then. I just loved the humor that ran through that whole group of people. I mean, Tinguely was very funny, and it was I-don’t-give-a-damn French humor. Writing about him was a gas, just enormous fun. The same with Bob Rauschenberg, on top of which Bob was a fantastically good talker. My first piece about him was very, very heavy on quotations, and he, in particular, was thinking and working in ways that fascinated me.

RK: Meaning what?

CT: Well, first of all, he was absolutely uninterested in self-expression. I still thought art was a form of self-expression. Not with Bob. He’d say, ‘I think it ought to be more interesting than that.’ And then Cage, of course, was hugely influential for me. His mind was like a grown-up version of Rauschenberg’s. Cage once told me that he and Bob thought exactly the same way, that one would say things the other could have said. I enjoyed being around these people and seeing how they interacted. I felt that they were much livelier to listen to than writers. The other thing that struck me about Bob was that he always talked about art being, for him, a collaboration—with people and with materials. He wanted to let the materials take their own place in what he was doing. It’s why he went around to hardware stores and found out-of-date paint cans whose labels had come off, so he wouldn’t know what color it was going to be. It was this whole idea that art could be a collaborative effort, rather than a heroic individual effort. I mean, these artists had huge admiration for Pollock and Rothko and de Kooning and Guston. But they were very scornful of the rhetoric around Abstract Expressionism, the idea of the solitary genius, the ‘I, alone, in the wilderness have come to this act of great creation’ thing.

RK: A lot of that was also metaphysical, communing with the oversoul, searching for the absolute abstraction, that kind of thing.

‘In those days, you’d turn in a piece and sometimes you wouldn’t hear anything for weeks. I couldn’t stand it. I’d finally make an appointment with Shawn...and he’d say, ‘Oh, Mr. Tomkins, I’ve been trying to get in touch with you!’ Absolute lie.’

CT: The next generation really wanted to break from all that. And everybody says this, but I think it’s true that Rauschenberg and Johns were the ones who led them out of the Ab-Ex stranglehold. They were also having a very good time doing it. It wasn’t all angst and suffering. That was very important. They were fundamentally opposed to the heavy moralistic aspects of Abstract Expressionism.

RK: I want to back up for a second to ask what you recall from your early days of working with William Shawn, being around him.

CT: Well, of course, we all basically worshiped at Shawn’s temple at that time. I had very few dealings with him. I had another editor who dealt with me directly, Gardner Botsford, and that was another marvelous piece of luck. Gardner had the kind of eye that could see where something was a little off or the piece was weak, and he wouldn’t change it himself, just suggest that maybe you could do a little something here or there. And all of a sudden you saw the same thing he saw. Shawn read everything, of course, and before writing a piece, I had to go to him and get his approval. He always called me Mr. Tomkins. Everybody was Mr. or Mrs. or Miss with him. In those days, you’d turn in a piece and sometimes you wouldn’t hear anything for weeks. I couldn’t stand it. I’d finally make an appointment with Shawn and go to his office, and he’d say, ‘Oh, Mr. Tomkins, I’ve been trying to get in touch with you!’ Absolute lie. Magazines could still function like that back in those days. There’s a wonderful story about Kenneth Tynan, when he was the theater critic for the magazine. He did a profile of Mel Brooks, and as soon as he finished it, he began getting calls from the Mel Brooks organization, the PR people, who wanted to know when it would appear and were very frustrated that he couldn’t give them a date. They were saying, ‘You have to run this right away, before the movie opens!’ And Tynan said, ‘What you don’t understand is that Mr. Shawn is unalterably opposed to topicality.’

RK: Did that give you time to just hang out over long periods with artists, the way Joseph Mitchell seemed to spend his days with cops and oystermen and bartenders? Did you spend a lot of time socially with artists, going out?

CT: The Cedar Tavern scene was pretty much over by the time I came along. Max’s Kansas City became the place where artists were, but I don’t remember spending a lot of time there. I had a family, and for part of those years, I lived outside the city. But I did spend a lot of time at Rauschenberg’s studio and house on Lafayette Street, where I’d see plenty of artists. Both Bob and Jasper Johns loved to cook. Bob would cook for 10 people at a time.

RK: You didn’t end up doing a full-dress profile of Johns in those early years, and you finally got him to submit to one fairly recently, in 2006. Did his absence from your profiles of that group trouble you?

CT: It did, but he was just very dubious about talking for publication about himself and his work that way. And what happened also was that the breakup between Bob and Jasper was very severe. And because I saw quite a lot of Rauschenberg, I guess I felt, at a certain point, uncomfortable about trying to do Johns.

RK: It was like a divorce, and you ended up on the Rauschenberg side of the divide?

CT: More or less. But I also want to say that, from the beginning, I never thought that I was trying to compose a comprehensive picture of the art of our time or anything like that. I was aware and am aware that there are whole areas of art I’m just not that interested in. I always wanted a profile to be a good story, and some work and some artists just didn’t do that for me, despite their importance.

RK: I noticed in reading the collected profiles that it was a good number of years before you used the first person at all.

CT: In the beginning, I felt that I, the writer, should be invisible, complete transparency between the subject and the reader. And then I began to realize that it would be a lot more fun if I let myself enter the piece more often. When the New Journalism came along, I never went into it with both feet, but my writing did change. Largely because of Rauschenberg, I got the idea that I wanted my profiles to be collaborations and that I wanted to choose subjects whom I not only could get along with but who would be interested in the experience, who would sort of open themselves up to the process, with the idea that maybe they could learn something, too. I began thinking of the profiles as experiments. I wanted to just put things together and let them resonate without too much artifice. I don’t know how often I was able to do that, but that was the ambition, anyway.

RK: And you’ve always made very clear that your writing does not function as criticism.

CT: I just didn’t feel that pure criticism was something I could do. I didn’t think I’d be good at it. And frankly, I didn’t want to. I mean, I’d been very influenced by the critics of that period, by Greenberg, and Rosenberg, and particularly by Leo Steinberg. But I just didn’t have that frame of mind. Very often I used to think that I never knew what I thought until I saw what I wrote.

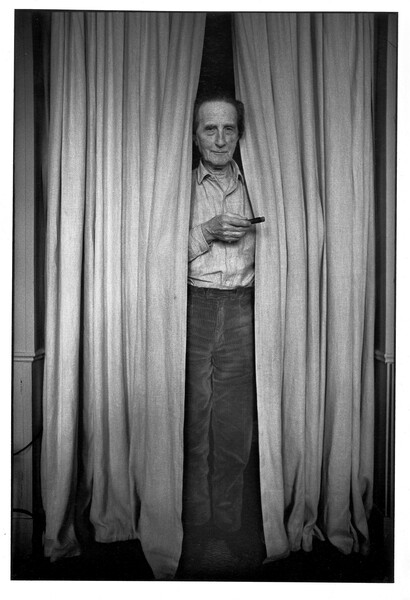

Marcel Duchamp, New York, 1965–67 Photo: © Ugo Mulas Heirs. Courtesy Archivio Ugo Mulas

RK: There’s that great statement by E.M. Forster that’s almost exactly that, where he says, ‘How do I know what I think until I see what I say?’

CT: That’s it! I’m happy to hear that—I’m a huge Forster fan. I just always had the feeling that the writing came out of my hand; it was in the making. And that’s not the way most critics function.

RK: When you look back now, are there people you wish you had written about?

CT: Certainly Eva Hesse. I thought she was terrific. But she died so young, and it just never happened. I also think Sol LeWitt would have made a great story, but for some reason I never wrote about him, either. Or Cy Twombly.

RK: Warhol also seems to have been a gap for you early on. You wrote about him in 1970, but it wasn’t for ‘The New Yorker.’ It was a catalog essay. And then you did write about him later for the magazine, in 1980 and then again in the ’90s, after his death, but they were not traditional profiles. You wrote that the one time you interviewed him, for the catalog essay, he brought along his own tape recorder and asked you the first question, which was, ‘Do you have a big cock?’ And you thought he said ‘clock’ and were a little confused.

CT: I remember that interview pretty vividly. I’m afraid that somewhere in ‘The New Yorker’ I did write, probably in the ’80s, that he was a clever minor artist. And the thing is, that’s what I thought at the time, and so did Robert Hughes.

RK: Hughes pretty much continued to think that, but it seemed like your feelings changed over time.

CT: I began to realize how important his influence was on so many artists I admired and that it was a big mistake to undersell him. But I did have the feeling that he was being given credit for things that Duchamp had done a lot earlier, in questioning the definition of art. I was just sort of blind to his accomplishments and didn’t look at them as closely as I could have. But that comes with the territory of writing about art being made in your time.

RK: I want to circle back for a minute to the importance to your writing life of Gerald and Sara Murphy, particularly Gerald.

CT: In Snedens, I used to just go over and talk with him, and he welcomed it. He became like a father figure, as important to my development as Duchamp. I think, having lost his two sons at such an early age to disease, he might have looked to me as a surrogate son. And I was deeply fond of him and of Sara, who was an extraordinarily compelling person to be around.

RK: He died in 1964, so it wasn’t all that many years that you got to be around him. How often did you see them?

CT: I don’t remember going for dinner a lot but for tea or for champagne cocktails. Gerald had a special recipe for champagne cocktails, and when somebody would ask him what the secret was, he’d say, ‘Oh, it’s just the juice of a few flowers.’ And Sara would sit on the porch of their house and say, ‘You must always, after drinking champagne, look up into the trees.’ They were the kind of people who said things like that convincingly, with no irony whatsoever. For quite a while, I tried to persuade him to write: ‘You had all these amazing experiences in the ’20s, in that great period, and you really should write them down.’ And he’d say, ‘I have far too much respect for the art of writing. I would never do that.’ So at one point I said, ‘Well, how would you feel if I tried doing it?’ And finally they agreed, though Sara was always more reluctant than he.

RK: What was the process?

CT: It was the first time I ever used a tape recorder, because I knew I wanted to write something longer and in fine detail. I remember lugging this huge reel-to-reel contraption down to their house, two or three times a week in the afternoon. I’d put it on the table, and Sara and her two pugs would sit on the sofa, and the pugs would go to sleep immediately and begin snoring very loudly. You can still hear it on the tapes.

RK: Why do you think he became so influential for you, aside from being just an interesting person to be around?

‘I began thinking of the profiles as experiments. I wanted to just put things together and let them resonate without too much artifice. I don’t know how often I was able to do that, but that was the ambition, anyway.’

CT: He gave me a lot of real encouragement and was very intrigued by the artists I wrote about. He convinced me that what I was doing was a form of literature and not just journalism. And you have to understand that by that point in his life, he had completely banished art from his thinking. He had painted for only about seven years, in the ’20s, and after his sons died, he stopped and completely turned his back on that work. I didn’t realize how important his paintings were until many years later. He never even mentioned them. I think the other reason, later, that Gerald and Sara came to loom so large was my feeling that the New York art world in the ’60s had a lot of parallels with what was going on in Paris in the ’20s, very much the same kind of excitement and broad openness and sense of discovery. And I realized how lucky I felt to be living then and writing about it.

RK: One of the last things I want to ask you, because all of these conversations over the last many months have been the three of us sitting together—you and me and Dodie—is about how your writing life changed when the two of you got together. And, Dodie, how yours changed as well. People in the art world speak of you as a kind of hybrid operation, a hyphenated creature, the Tad-and-Dodie, doing all of your interviews together and then writing separately. Can you tell me a little about how you met?

CT: Boy meets girl? More like girl meets middle-aged man. [Laughs] We met when she interviewed me, which was something I had never experienced.

Dodie Kazanjian: I was the Washington editor of ‘House & Garden.’ And I was also the editor of a magazine at the National Endowment for the Arts called ‘Arts Review.’ I was working on a special book issue about support for artists by collectors, dealer, critics and curators [‘Portrait of the Artist, 1987: Who Supports Him/Her?’]. Tad was one of the critics I wanted to talk to. The first thing he told me was that he wasn’t a critic! Frank Hodsoll, who ran the National Endowment, read the interview and thought it was terrific, and asked me to invite Tad to come to lunch in his office, which he did. And then in exchange Tad invited me to come to New York for Warhol’s funeral.

RK: Seriously? What an auspicious occasion to launch a relationship! [Laughs]

CT: Well, her plane was late, and she ended up missing the funeral, but there was a big lunch afterwards, at the Paramount Hotel in the space that had been Billy Rose’s Diamond Horseshoe, the famous nightclub. The whole art world was there. Practically everyone I’d ever written about.

DK: What I remember is a huge ice sculpture and that when you went down the big winding staircase, it was lined with covers of ‘Interview’ magazine. This was 1987. We ended up talking on the telephone a lot after that, Tad here and me in Washington. We started talking about maybe doing a column together for someone. And once, when I was having trouble with a piece for ‘Vogue,’ due the next morning, he said, ‘Let’s talk it through.’ And he talked me through it for an hour and a half.

CT: I think that’s where it began, me helping you, and then gradually, more and more, it became the other way around, you helping me.

RK: When did you begin reporting together?

DK: It started the summer we got married, with our biography of Alexander Liberman, the artist and éminence gris of the Condé Nast empire [‘Alex: The Life of Alexander Liberman,’ published by Knopf in 1993]. That’s when we began doing interviews together.

CT: I realized immediately that she was a very good interviewer, that she could get people to say things I never would’ve been able to. And she was writing about artists for ‘Vogue’ who tended to be younger than the ones I knew about.

RK: Would you sort of play good cop, bad cop in interviews?

DK: No, not that. It’s just that I’m not afraid to ask a stupid question.

CT: I’m much more inclined to take an organized approach, and Dodie is much more intuitive. I could tell right away that people were more comfortable with her. She immediately put people at ease.

DK: I’m also not afraid to ask questions about more personal things—how people’s lives work—in a way that I think Tad is hesitant to do. Also, because he’d been doing this for so long and was so highly regarded, some artists, particularly younger ones, would get intimidated—feel obliged to sound intelligent and not be themselves.

CT: When the two of us are there, the game of being interviewed is much better. It’s always a game. A two-way street.

RK: I’m very grateful for getting to go down that street with you.