Essays

Maria Lassnig: To Be Many Kinds

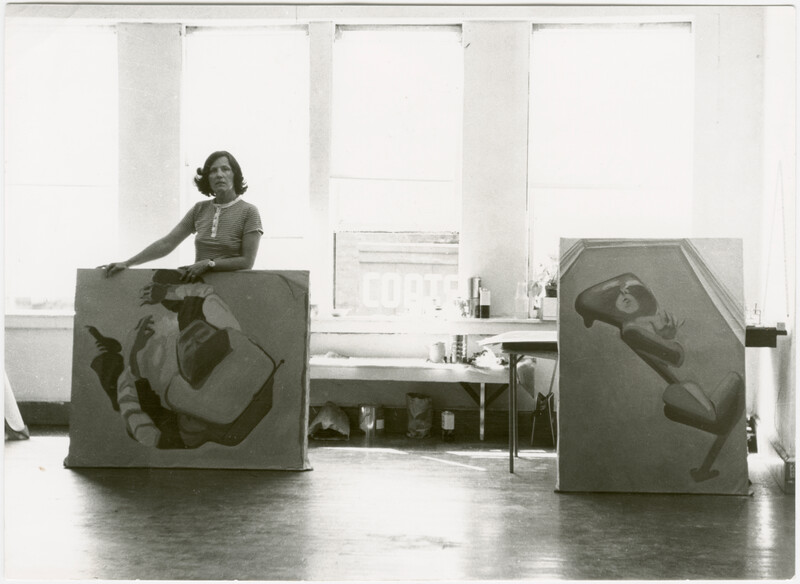

Maria Lassnig at Studio Avenue B, New York, c. 1969 © Maria Lassnig Foundation, Courtesy Maria Lassnig Foundation Archive

To mark the centenary of Maria Lassnig’s birth, voices from her life and work are assembled by Gesine Borcherdt. The painter Maria Lassnig (1919 – 2014) pioneered a daring, deeply psychological version of postmodern figuration, and during her long career—which remained in the shadows until she was in her 60s—she orbited within a farflung social solar system of artists, writers and curators. On the centenary of her birth, a host of voices assemble to commemorate her life.

Maria Lassnig, Kleines Sciencefiction-Slebsporträt (Small Science Fiction Self-Portrait), 1995 © Maria Lassnig Foundation

Hans Ulrich Obrist

I met Maria for the first time when I was 17 and went on holiday to Vienna with my parents. I had started visiting artist studios during high school—and it was actually Rosemarie Trockel who gave me the idea to ask in every big city for the overlooked female artist, kind of like the Louise Bourgeois who had just come to recognition in that time during the ’80s. When I went to Vienna, everyone told me that ‘Louise Bourgeois’ was Maria Lassnig. So I skipped the tourist program of my parents and instead gave Maria a call. And she was very open to meet a teenager! I spent an hour with her in her studio and she explained so much to me. Very quickly it became clear to me that she had invented something totally new in painting: Her idea ‘body awareness’ had really anticipated Vienna Actionism—even though she never left the area of painting. A few years later, I started curating exhibitions. In 1993, Kasper König invited me to co-curate the show ‘The Broken Mirror’ at the Kunsthalle Wien, traveling to the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg. It was a show about painting. We approached it with artists from different generations, including Eugène Leroy and Leon Golub—but Maria was the center of the show, even showing her animation films, which were not well known at that time. This was very intriguing for then-young painters like Marlene Dumas and Luc Tuymans. And it was the beginning of a deep friendship between Maria and me.

Matthias Mühling

‘The Broken Mirror’ was where I first saw Maria’s work! It was a time when nobody was looking at painting. Even though Maria was always kind of visible, she stayed more in the context of Austrian art. Even in the mid-’80s, museum directors were not interested in showing or buying her work. This truly only changed when the Mumok in Vienna had a big exhibition in 1985. Until then, she had never had a retrospective. When we approached her about one once, she said, ‘A retrospective is for old or dead artists. I am a contemporary artist! I want to show my new work and nothing old.’ She said it in a way that you wouldn’t argue with. I found this extremely impressive: to constantly make new work at the age of 90 and not to be pocketed by a retrospective look. I mean, there are hardly any artists who make new work when they are 70.

Maria Lassnig, Selbstportät, als Zitrone (Self-Portrait as a Lemon), 1949 © Maria Lassnig Foundation. Photo: Roland Krauss

Maria Lassnig, Mutter und Tochter (Mother and Daughter), 1966–67 © Maria Lassnig Foundation

Peter Pakesch

Most artists start repeating themselves after 40 or 50. She didn’t. All her life, she had this gigantic inner freedom to do whatever she wanted to do, like Picasso. She even once called herself ‘Madame Picasso.’ But of course, she realized that she was not getting the same attention as all those male artists.

Gabriele Wimmer

In the ’90s, the museum landscape was very male. Also, many museum directors didn’t touch Maria’s work—because they were scared of her. She was not just a woman, and thus rated on a lower level, but she was a difficult character. She was sort of a split personality. She could be incredibly sweet, writing the most beautiful letters, and the next day she was the opposite. I never really understood why. Maybe because she was treated badly by some of her lovers throughout her life. And her whole family situation, how she grew up in the 1920s in Austria, was really tough. Something obviously went very deep and later came out this way.

Maria Lassnig, Sciencia, 1998 © Maria Lassnig Foundation

Maria Lassnig, Zwei Arten zu sein (Doppelselbstporträt) (Two Ways of Being [Double Self-Portrait]), 2000 © Maria Lassnig Foundation

Peter Pakesch

Maria’s childhood was extreme, in all senses. She grew up as an illegitimate child in the Austrian countryside, in Kärnten, raised by her grandmother. That was really tough. Then the mother married a baker and they moved to the city of Klagenfurt. So they didn’t suffer from hunger as many did at that time, but Maria certainly knew what poverty was. Her mother must have been a very dominant woman, but Maria had a close relationship with her. Her death would later become an intense topic of Maria’s paintings. Her mother supported Maria’s talent and sent her to drawing lessons early on. When Maria was 10, she was able to copy Old Master drawings from pictures she had seen on postcards. But her mother, who was practically minded, urged her to become an elementary school teacher. Maria even started teaching, but it was not easy for her. So she rode a bicycle from Klagenfurt to Vienna—which took her two days!—in order to enter the art academy. She got accepted and was a very good student. At a certain point she got into trouble with her teachers. It was for artistic reasons. As she was thinking ahead artistically, she didn’t fit into the ideology of the Nazi era. It was not about obvious politics. She just didn’t compromise.

‘I think there is this very special space she’s dealing with. And she was able to find a representation for it—elements and events and situations which don’t really belong to the figurative register.’—Catherine David

Liz Larner

Maria was fierce! We did this show together called ‘Zwei oder Drei oder Etwas’ [‘Two or Three or Something’] at the at the Kunsthaus Graz in Austria in 2006, curated by Peter Pakesch, together with Adam Budak. And there is a story that completely explains the experience: I usually write a list of people I want to thank after every show because there are people I want the acknowledge who helped me along. I gave my list to Peter, and he asked Maria for her thank-you list—but she never turned one in. So I asked, ‘Maria, don’t you have anyone you want to thank?’ And she said, ‘No.’ I loved her for that! It was like: Bang! So good. She did it all by herself! I’m sure there were those along the way that helped her, but she mostly did it all alone.

Maria Lassnig, Selbsportrait (Self-Portrait), 1945 © Maria Lassnig Foundation. Photo: Roland Krauss

Mühling

It was amazing how she set up her career again and again, in all these different places. Starting out in Vienna, moving to Paris in 1960, then to New York in 1968—she was almost 50!—then a year in Berlin in 1978, another year in New York, and in 1980 she moved back to Vienna. And she always did it against the odds, totally on her own and without any money, without ever complaining about it.

Martha Edelheit

She came to New York with absolutely no money. Nobody knew who she was. But she was funny and stubborn and very sure of herself. I met her when she had just moved there, and we became good friends. She lived in a loft in the East Village, right near Tompkins Square when it was a drug haven. And she said, ‘Oh, it’s so wonderful in my building! People are there all day and all night’ You walked up the stairs to the building, and it was covered with discarded needles and trash and cat and dog shit. It was incredibly awful! But she said she felt safe! She lived with the most minimal amount of materials. She was determined to do what she wanted to do. She moved out only after someone broke into her place and stole her camera. Afterwards, she lived on Spring Street and West Broadway in SoHo. But even there, her life was stark: She had one cup, one saucer, one spoon, one plate, one fork, one knife, one glass. When she was given a big Austrian art award, all these formal people came to her place. They stood in a circle and said how important she was, and they crowned her with laurel leaves. They brought a bottle of champagne, but we ran out of plastic champagne glasses, and there was literally nothing to drink out of. I think they were quite taken aback at the total sparseness of how she lived. But like many artists, when you did have some money, you spent it on supplies and materials; you don’t buy another cup. I think the first time she had money was when she got the professorship in Vienna. As much as she loved living hand-to-mouth in New York, I guess she was happy to get some financial stability late in her life.

Hans Werner Poschauko

She was 60 when she got this professorship. And it was the first time she really could live off of her art. Before, she always had to do other jobs: In New York she was making portraits and backgrounds for animation films. In Paris she was writing articles for Austrian newspapers to get by. She could never even heat her place properly. In the winter it was very cold. Can you imagine living like that for so long? It’s kind of unthinkable today. She really was a major role model for artists of my generation. She told us students, ‘As artists, you have to be prepared not to make any money.’

Catherine David

When I worked with her for documenta X, of course she mentioned she had been left aside. But I would not say she complained. She was just very realistic. She knew what had gone well and what went wrong. But she gave it a very positive meaning, with a kind of humor. If you see the few videos she did, it is obvious: She was very humorous, but at the same time, there was something very deep.

Edeltheit

We were both part of this group called Women Artist Filmmakers that we founded in New York with other artists, including Carolee Schneemann. All of us were either painters or sculptors or both, and we wanted filmmaking to be an extension of our work as visual artists. Maria fit into that completely. She was amazingly inventive. She didn’t have any money. For her films, she used a couple of bricks she had found on the street, a piece of broken milk glass from the garbage can and a Bolex—a 16 mm hand camera—that she had gotten from a pawn shop for maybe 10 dollars. She would work frame by frame by frame. And her films were wonderful! The animations were so different from what everybody else was doing. Her self-portrait film, which was of the first ones I saw, was so moving. It was a portrait of herself that merges into Greta Garbo and her mother and all these different personas, but she is still always somehow herself. It’s a powerful set of images. I think the self-portrait film reflected who she really was as a person. In many ways, that film is close to what she did in her paintings. It’s more isolating in terms of transforming her into different kinds of images, and that’s what her paintings are about. That’s a film she did in 1971, and yet her late paintings that she was doing in the ’90s and 2000s were very related to it, in the way she isolated herself. She left a lot of open space, whether she was doing a self-portrait with a gun or a self-portrait just sitting there, staring out at you. It’s a shame that in those early years, in the ’70s, she wasn’t showing her paintings in New York very much.

Wimmer

Living in New York didn’t have any effect on her sales. She earned money by doing commissioned portraits, but nobody wanted to buy her actual paintings. Of course, that was also because she was a woman. At Galerie Ulysses, we had our first show with her in 1988—she had joined the gallery just because my business partner, John Sailer, had planned to set up a gallery in New York. And that’s where she wanted to succeed. But the market was difficult for her. Very few museum directors were interested in her. We really had to work hard. It’s very different from today, when the museums are coming all by themselves, unasked. Still, there were a few great offers from international museums. I will say that Maria also refused a lot of offers. I think she was kind of shy and maybe even afraid of an international career. She had a kind of avoidance tendency—if you asked her to do a show, it happened five years later.

‘When Maria felt something, she felt it 20 times more than anyone else. Depression or desperation would go deep into her body and wouldn’t disappear for hours.’—Hans Werner Poschauko

Obrist

Maria had a lot of doubts about doing an exhibition at the Serpentine in London. She didn’t think it would be a success. This was in 2008, and she was still unknown in England. A week before the opening, she wanted to cancel because she thought the ceilings were too low. In the end, she did it, and it was a huge success. The English press celebrated her as the missing link between Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud. So she was really very happy the day of the opening.

Peter Eleey

You could consider her pessimistic I suppose. But she also had this wicked sense of humor. She told me that no one was interested in her work in New York. ‘Why would I want to make an exhibition there?’ Of course, that reflects the 12 years that she lived there receiving minimal recognition for her painting. Yet she told me she had moved there from Paris because Nancy Spero had told her that the place to go as a woman artist in the 1960s was New York City. So our encounter in early 2011 was like the end of a long wait since her departure from New York in 1980. Eventually she recognized that there was a great interest in her work over here, and luckily she lived long enough to read the many great reviews that were written about our show. I think this was very gratifying for her.

Poschauko

I remember she flipped through all these reviews in disbelief. But on another level, she knew herself extremely well, and she knew how other people would see her. Once a collector came by with a museum director. Before they came, she said, ‘Now I need to change.’ And she put on a pair of old jogging trousers with moth holes and a pullover that was full of holes, too. She laughed and said, ‘It looks better like that!’ Then the door bell rang and her face changed. The collector said, ‘Maria Lassnig! How are you?’ And she said, ‘Can’t you see? Very bad. I am being misunderstood. Nobody likes my work.’ The collectors answered, ‘But you just had a big exhibition at the Lenbachhaus in Munich, and everybody respects you and your work!’ She shook her head and said, ‘No.’ It was so funny! Then the two look at her paintings and the collector bought some of them for quite a large amount of money. He said, ‘This is the happiest day of my life!’ And Maria said, ‘This is my worst. You have stolen my paintings.’ The minute he was out of the door, she starts laughing and changes her clothes. There are so many stories like that. With Maria, there was always a little bit of show involved…

Mühling

I remember that she would never throw away any food but rather cut off the moldy part to save what was edible. She did this even with her famous apple pie before she offered it to you.

Maria Lassnig, Iris (still), 1971 © Maria Lassnig Foundation and sixpackfilm

Maria Lassnig, Iris (still), 1971 © Maria Lassnig Foundation and sixpackfilm

Obrist

You couldn’t refuse to eat her apple pie! I actually don’t eat sugar, but there was no way to get around it.

Mühling

Well, she had lived through World War II, so this was in some ways typical for her generation. She was annoyed, for example, when she would get big fruit baskets because she felt obliged to eat them all. It’s true that she totally knew how to stage herself. Just look what she did for photographers! If you came across being dominant as a woman, at the time when she built her career, you quickly got the reputation of being difficult. Men could always push forward and be loud and be the first to talk, but when women did that, and this is still the case today, it was seen as negative. So Maria had to also be disarming, and she had an incredibly charming way to give herself an eccentric look, long before the selfie age. Just look at her glasses! Peggy Guggenheim had nothing on her.

Elfie Semotan

I thought she wasn’t vain because she always painted herself in such a brutally honest way. But I was wrong. It was completely different in photography. Her painting is all about a translation of her personality, her thoughts combined with what happens around her and her role in society. But doing something like a self-portrait photograph for the German Zeit Magazin was a completely different matter. She was very clear about what she wanted. She looks very focused and intense. It is not a sensational photo in the sense that she is not doing anything crazy. But she comes across as incredibly concentrated and consequential. It took her two years to like the photo!

Pakesch

What really amused me was her youthfulness. When you saw her from behind, she always looked like a student, no matter how old she was—also because she would always wear sneakers. She was the first to bring sneakers from America. This was completely unusual in Vienna, to wear that kind of shoes, especially as a woman. She did it with such a coolness. And she would always wear colorful clothes, so she seemed very juvenile, even when she was old. That made her extremely likeable.

Poschauko

She really enjoyed dressing up and going to openings. She would put on a tie, a dress, a coat and her sneakers. She looked amazing! But when it came to meeting with people, she would do it only one-on-one. Never in a restaurant but at her studio apartment, in part because she didn’t want to spend money on lunch or dinner, but also because she was very sensitive to noise. When Maria felt something, she felt it 20 times more than anyone else. Depression or desperation would go deep into her body and wouldn’t disappear for hours. She simply couldn’t handle talking to more than one person.

Mühling

I mostly only met her one-on-one. The meetings had an amazing quality. She wanted to know exactly what kind of person you were. She was absolutely focused on the conversation and also on talking about her work. Today, it’s normal that you deal with assistants and gallerist and art handlers. With Maria Lassnig, it was only Maria Lassnig. The choice of paintings, the work on catalogues—you would deal only with her, nobody else, which made you feel very exclusive. There was no e-mailing. When she wanted to talk about something, you had to get on a train and come to her. And, of course, you did.

Poschauko

She spent a lot of time by herself. This was very important for her art. She often blocked out the world, especially towards the end of her life, when more and more museum directors, gallerists and collectors wanted something from her. She didn’t want to confront them. She just wanted to be in her studio and paint. Sometimes I picked up the phone when a museum director would call and offer her an exhibition, and she would shout from the back of the studio: ‘Hang up! Cancel it all!’ She was very strict with that. She said everything just the way she was just thinking it. There was no filter. She was extremely direct, and she offended lots of people with this behavior. Sometimes she would even kick people out of her studio. This was, in a way, self-protection because of her hypersensitivity. Any kind of rejection—also from partners in her personal life—she felt much stronger than other people.

Pakesch

The writer Oswald Wiener, a lifelong friend and also a lover in the 1950s, who later ran the famous artists’ restaurant Exil in Berlin, described her incapability to deal with groups as a kind of autism. Once she was in a group, there were always misunderstandings. One-on-one, she communicated much more precisely, in a very intense way. Especially with the younger men who played a role in her life: Arnulf Rainer, Oswald Wiener, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Friedrich Petzel, Iwan Wirth and myself. She couldn’t deal with women so well. She didn’t get along with Valie Export, for instance, with whom she shared the Austrian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. All in all, she was a person who really enjoyed being alone. So towards the end of her life, she was in misery because she had these people around to help, and she did everything she could to kick them out of the house. She was extremely stubborn and contradictory. But this was also her artistic quality—a kind of obstinacy that was rare, combined with an enormous talent that was always there.

Poschauko

A lot of stories make her seem grumpy and lonesome, but this wasn’t the case. This was a self-chosen loneliness. She could work only this way—absolutely focused on painting—because the painting was all about her body awareness, the feeling of the body. It is extremely important to understand how she experienced that: Where does it hurt? And then the painting happened. The body awareness would last for three or four hours—and in that time she made a painting. And she was extremely fast in transforming this feeling! She always said, ‘The next day, I can’t get the feeling back, so I have to do it now.’ In fact, the next day, the maximum she could do was paint the background. So all her paintings were made in a very short amount of time, experiencing her unique kind of body sensation. If you look at her catalogues, you might think her work looks grotesque or surreal, but that’s not what it was. She lived through all these things. She related the colors she used to emotions—love, hate, loneliness, depression. She was very precise about this. The forehead would get a thought color, the nose a smell color, the pain would get its own color and so on. It was a system she had been working on since 1949. That year, she recognized the feeling for the first time, sitting on a chair and feeling the chair melting into her. She funnily called it the ‘buns feeling.’ Later in her paintings, she would melt into animals or machines.

Maria Lassnig, Baroque Statues (still), 1970–74 © Maria Lassnig Foundation and sixpackfilm

Maria Lassnig, Palmistry (still), 1974 © Maria Lassnig Foundation and sixpackfilm

Eleey

One of the great things about Maria was that she was an artist who brought together the experience we have as individuals moving through the world as we feel things and as others see us. We acquired a great painting at MoMA from the 2014 PS1 exhibition, which is called Sciencia. In it, the figure of Maria is almost like a subject for an experiment, which I think the title alludes to. There are all these lines coming out of her body. She described them as lines of energy emanating from her. The idea of using one’s work in the studio to dig deeper into oneself and, in turn, to find a vehicle for sharing that with the world—that’s so much a part of what makes all great art great. I think that was key to Maria’s entire way of working. Her earliest self-portraits have that. There are these binaries in her work, of inside and outside or of human and animal. In a number of self-portraits, she is with some other creature; it’s the idea of a ‘creaturey’ life as distinct from human consciousness. We find these things throughout her entire work. It actually isn’t a sense of different identities; it’s more Maria digging into herself in different ways. And as she feels different things over the course of her life, those representations of herself change.

Obrist

Her body awareness was constantly changing and showing up in totally different ways in her paintings. She appears as a Cretan bull. She appears with virtual reality glasses as a science-fiction figure. She appears on a different planet, with a Janus face, with a third eye. The idea behind this is that we have different identities, that identity is fluid—which is one of the main reasons why many young artists today are interested in her. Her reception has in some ways just started. There are so many great exhibitions you could do with her, just by picking one aspect of her work: her animations, her drawings, Greece, science-fiction, country life, animals…it’s endless! There are only very few artists—Picasso, Polke, Richter—whose work is so complex that you could do easily 50 exhibitions with them.

Pakesch

What makes her work so unique is this incredible sensitivity and versatility. And it’s astounding how she sticks with the same topics and looks at them from so many different perspectives, constantly generating something new from within her own work. It is an artistic attitude that doesn’t really fit into the era of late modernism; it has much more to do with contemporary art. For a long time, people didn’t understand how she dealt with the abstract and the figurative, the inner and the outer body, and the meanings she gave to color. It was amazing to see her work at Tate Liverpool, parallel to a Francis Bacon show. You could see that these were two different eras. They were born only 10 years apart—Bacon in 1909, Maria in 1919—but she looks so fresh! Her work fits much better with Kippenberger than with Bacon, even if Bacon was important for her.

David

In the second half of the ’90s, she was working on drawings and doing, from my point of view, very interesting ones, so I wanted to focus on them for documenta. They showed what was between different realities. I think there is this very special space she’s dealing with. And she was able to find a representation for it—elements and events and situations which don’t really belong to the figurative register. It was also a way of drawing engendered by an attention to performance, to the movement of the body, the feelings of the body.

Maria Lassnig, Iris (still), 1971 © Maria Lassnig Foundation and sixpackfilm

Maria Lassnig, Baroque Statues (still), 1970–74, 14 minutes, 55 seconds © Maria Lassnig Foundation and sixpackfilm

Poschauko

Maria had two concepts of perceiving the world: one way was watching with open eyes, which is looking at reality, and the other way was looking with closed eyes, which is an introspection so that body awareness can come onto the canvas. There is a painting called Zwei Arten zu sein [Two Ways of Being]: It shows her with open eyes, painted in a realistic way, and also with closed eyes, rendered in more abstract shapes, visualizing emotions. She really was the most complex person I ever met in my life.

Pakesch

She was an absolute master of color, in putting them next to each other and creating space. This is a quality that you find in the best Impressionist paintings. You can see this especially in her abstractions from the early ’60s, which many connect with Willem de Kooning’s work from the ’80s. But she did it much earlier. And the fact that she gave a meaning to each color—I guess this could be connected to a kind of synesthetic experience. Apparently, Alexander Skrjabin could hear colors and see sounds. I can imagine that, for Maria, it was a similar thing with colors and language. She was extremely strong with words. The titles of her works were very important to her. And her diaries feel like philosophical texts. In fact, she had a very close friendship with the poet Paul Celan.

Obrist

We had a very close penpalship. I’ve got about 50 very long letters from her—in fact, she left a last, unfinished letter to me on her table before she died. We are now publishing a book with these letters. Her polemics against photography are especially intense in these letters, her claims that painting has to go where photography doesn’t.

Semotan

Towards the end of her life, she had an exhibition in Graz, where I met her. She seemed pretty weak, sitting in a wheelchair. I thought that she probably wouldn’t remember me. So I went up to her and said, ‘Maria, could you sign the catalogue for me? Do you remember me?’ And she laughed and said, ‘Of course!’ So she signed it and wrote, ‘For the competitor.’ Can you imagine? She was still so funny, at that age! She really saw photography as her rival. This had not occurred to me until that day.

Larner

When we did the show together in Graz a few years earlier, I realized what a superstar she was in Austria. I thought that it was really cool that she was able, over time, to have that presence there. She was seen as a very strong person. I think that this was what she wanted and that she worked hard to maintain that kind of strict understanding of herself. Her work was incredibly expressive. She was kind of like Agnes Martin. They were similar in the way they were in their lives and in how they needed to live to do their work, and also in how they became revered, eventually, in their own countries and cities. I think it was part of their time that they had to be almost like art nuns, these sorts of singular women. They make me think of the goddess Athena, very tough and armored and totally singular and independent. Incredible! It felt like Maria had a shield so that she could do her work and not take on aspects of the culture that she was trying to make work against. I don’t think she called herself a feminist, but she certainly was a feminist in her own life. She did everything to have her world be her way.

Pakesch

She was always skeptical when it came to feminist or women-only exhibitions. When she went to New York, the feminist movement was new to her, and she would embrace it by joining a women’s filmmaker group. But she was not interested in politics in an obvious way, even if she could be quite political and feminist in the art itself. For instance, she made a painting called ‘ Traditionskette,’ with herself next to Velázquez, van Gogh and Munch. And in 1960, she painted herself with a mustache on the invitation card for a show at the Galerie St. Stephan in Vienna and called herself Mario Lassnig.

Lassnig at Studio Maxingstraße, Vienna, 1997 (crop) © Maria Lassnig Foundation. Photo: Heimo Kuchling

Edelheit

When you talk about things that happened 50 or 60 years ago, it’s very hard to perceive what it was like back then. I mean, we didn’t think of ourselves as women artists; we thought of ourselves as artists. The feminist movement really kicked off in the ’70s. It was a spinoff from left-wing politics, which was very radical. You know, we were all people who were born during and before World War II. I was born in 1931 and Maria in 1919. Maria grew up in the same world I did, except that she was living in a country that was occupied by the Nazis. I was living in America, which was at that time the bastion of democracy. I still remember when I went to visit her in Vienna. We were walking around town and came to a square and she said, ‘You see that balcony up there? That’s where Hitler stood and addressed us.’ I got goosebumps. So we both shared these very bitter memories from the war. We didn’t talk about it a lot, but it was deep back somewhere, and I think that some of Maria’s images do reflect that, because those are things that were there. But as artists, it was much more about our own perception of the world than it was necessarily about being a woman artist or being a feminist or being a political person. Yes, there are some women who use politics in their art in an explicit way, but I don’t think Maria did. Carolee Schneemann, who was part of our group, did it a little bit more. But in the end, it was always more about making art. If that makes it feminist, okay. But that’s not what defined the work.

Eleey

Maria was ruthless and fearless. I remember when I showed her my checklist of works for the show, she told me she thought the selection wasn’t tough enough—which was baffling. It’s funny to be told that by an artist, when you’ve included in the exhibition a self-portrait of the artist with her brain falling out of her head! And work about the children that she never had. She really bared everything for us as an audience. I tried to include as much of the joys as of the sufferings. But I think it is a mark of how rigorous and demanding she was of herself that she saw even a checklist like mine as not efficiently severe. You know, life is brutal. It’s just that she had the courage and the generosity to share that experience with us.

–

Oral history contributors include:

Catherine David

Deputy director of Musée National d’Art Moderne at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Martha Edelheit

American figurative painter based in Sweden.

Peter Eleey

Chief curator of MoMA PS1. Organizer of a 2014 survey focusing on Lassnig self-portraits.

Liz Larner

American sculptor based in Los Angeles.

Matthias Mühling

Director of Lenbachhaus in Munich.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries in London.

Peter Pakesch

Chairman of the board of the Maria Lassnig Foundation.

Hans Werner Poschauko

Austrian artist and curator. Student under Maria Lassnig and her assistant until her death in 2014.

Elfie Semotan

Austrian photographer.

Gabriele Wimmer

Curator and partner at Galerie Ulysses.

–

‘Maria Lassnig. Zarter Mittelpunkt / Delicate Centre’ is on view at Hauser & Wirth Zürich, 12 October – 19 December 2019.

In Shanghai at West Bund Art & Design Fair, ‘You Paint As You Are’ is a solo presentation of works by Maria Lassnig on the occasion of the centenary of her birth, 7 – 10 November 2019.