Conversations

Matthew Day Jackson in conversation with space-program engineer Don Eyles

Commemorating the 50th anniversary of the moon landing

Fabio Mauri, Luna (Moon), 1968 © Estate Fabio Mauri

The March 17, 1971 issue of Rolling Stone magazine carried a headline typical of the mock-screaming tenor of the publication in those days, but eye-stopping even so: ‘Weird-Looking Freak Saves Apollo 14!’ The ‘freak’ in question, Don Eyles, a young hippie-ish software engineer described as wearing ‘John Lennon glasses, a drooping mustache, long blond hair, black cords and shitkickers,’ had achieved a degree of celebrity the previous month after firing off a salvo of last-minute computer code that saved the Apollo 14 mission, the third to reach the moon, from a faulty switch that threatened to abort its landing. Yet in an unsung sense, Eyles—along with a group of fellow engineers at MIT—had already been a national hero for years, for the pioneering software they had developed that guided man more than 200,000 miles to the surface of the moon for the first time, on July 20, 1969, a watershed moment in American history and the capstone to a pivotal, tumultuous decade.

To mark the 50th anniversary of that event, Eyles—author of the 2018 book Sunburst and Luminary: An Apollo Memoir—sat down recently with the artist Matthew Day Jackson, whose work for more than a decade has explored the esoteric, darkly poetic implications of the interplay between technology and human evolution, in pieces drawing from inspirations as disparate as Buckminster Fuller, Borges, ‘Big Daddy’ Don Garlits, Life magazine, the first atomic bomb and Viking burial ships. These are excerpts from their conversation, conducted in Jackson’s studio in Brooklyn.

Matthew Day Jackson: So there we were. It was 2008.

Don Eyles: You were at MIT doing a residency. I was nearby but somehow we never met. A friend of mine was working on the installation of your show there [‘Matthew Day Jackson: The Immeasurable Distance,’ 2009, which riffed on aspects of the Apollo space missions, drag racing and Buckminster Fuller, among other subjects]. But then I made bold to e-mail you afterwards, and we became acquainted. And I visited your studio in…Where was it?

MDJ: It was in Gowanus, in Brooklyn, the same neighborhood we’re in now but a different place. Was the airplane in the studio when you were there? God, that was crazy.

DE: No airplane, but there were a bunch of the big astronaut figures who seemed to be assembled as pallbearers. What was the name of that piece?

MDJ: It was called The Tomb. It was based on a sculpture from the Louvre that I fell in love with, called the Tomb of Philippe Pot, from 15th-century Burgundy. It was a funerary monument. I saw that sculpture during my first trip to Paris, and I absolutely fell in love with that thing.

‘There’s geometry that I’ve always thought of as being ‘hopeful geometry,’ which is geometry that doesn’t have right angles’ —Matthew Day Jackson

DE: There was a coffin but I can’t remember what was in it. I certainly remember the astronaut figures. The way they stooped in those moon suits did remind me of mourning.

MDJ: The coffin contained a series of sculptures, sort of abstractions of the human form, melded with trees and plants. There’s geometry that I’ve always thought of as being ‘hopeful geometry,’ which is geometry that doesn’t have right angles. So the forms in the boxes were my sculptural expression of evolution and how I don’t believe that we’re just flesh and bone, but rather that the things we make are sort of appendages grown along the path of evolution.

DE: So it wasn’t that they were mourning anything in particular, their lost innocence after going into space or…

MDJ: No, but that is something I’ve been interested in, that particular loss of innocence that came with Apollo. My meeting you initially was a little bit like meeting a star or a professional athlete or somebody that you look up to without really knowing who they are. Only very recently has the figure of the programmer become more visible in our society.

DE: Did we feel invisible in those days? I don’t know if we felt invisible, but I certainly had no idea of the amount of attention we would eventually receive. When I was writing code, I did sometimes think to myself that, 100 years from now, somebody might study it from some completely different angle. There’s the whole question of whether writing code is an art form or not. I don’t have a strong opinion about that, but it’s certainly at least a craft. It’s not a deductive science.

MDJ: I initially learned about Luminary and Colossus [source code for the Apollo missions, developed by dozens of MIT engineers, including Eyles and Margaret Hamilton], when the art curator Bill Arning took me through the history museum at MIT. He pulled down this dusty box from a shelf, and as we sorted through it, I started to see that it wasn’t just code but things I could understand. Then, when we happened upon the part of the code that you guys called ‘Burn, Baby, Burn,’ that’s when it broke out of being a relic and became something I could understand. Because it recorded the personalities of the authors of this digital language that’s supposed to have no signature. For me, that’s when it emerged from technology into meaning, things I was thinking about at the time. The author became a person with a story. That’s what led me to want to know you.

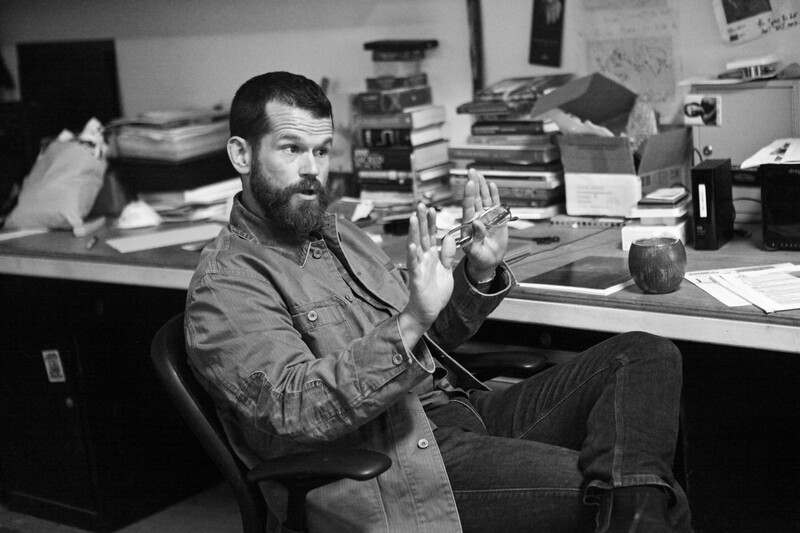

Matthew Day Jackson. Photo: Kenneth Bachor

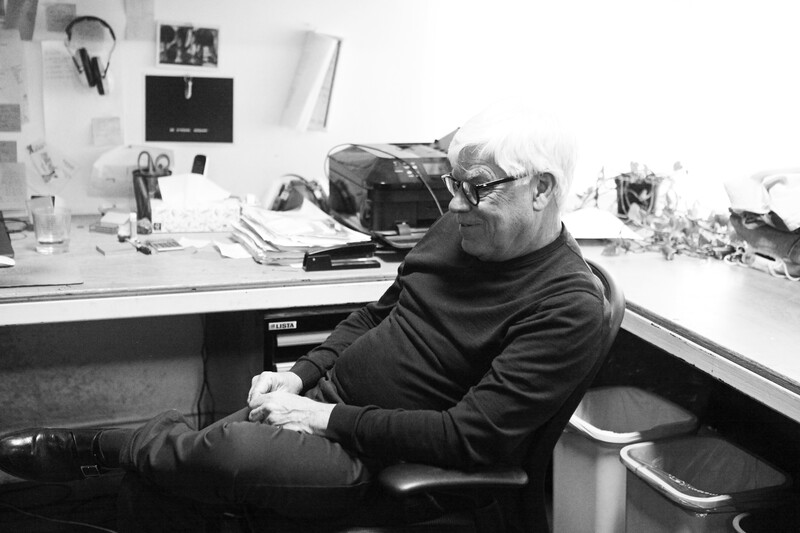

Don Eyles. Photo: Kenneth Bachor

DE: From my point of view, the art—if any—was in the code itself, not in the comments that gave a glimpse of who we were. The comments were just some of the froth around the top, as it were. But it is what people could fasten onto. The origin of ‘Burn, Baby, Burn,’ in particular, is interesting. My colleague Peter Adler and I worked on the code for the lunar module. We divided the mission into powered flight phases and coasting flight phases. He did the phases for the orbital maneuvering, the mid-course corrections and so forth. I did the lunar landing. We realized that we were duplicating each other’s code, because the procedures leading up to lighting the rocket, in each of those cases, were very similar. We would turn on the powered flight navigation system at the time of ignition minus 30 seconds. Because you’re in zero G, the fuel tanks tend to develop bubbles, so you need to do a little bit of thrusting before you light the main engine, to make the fuel settle in the bottom of the tank, so it’ll draw smoothly. That’s at seven and a half seconds before time of ignition. At minus five seconds, we always gave the astronauts a display that offered them the opportunity to approve the burn. If they didn’t press the button during that five seconds, we didn’t light the engine. But at time of ignition, it’s lighted. At some interval after that, the engine needs to be throttled up to its maximum thrust. All those things were somewhat in common, with a few variations for what Peter and I were doing. So we ended up writing one piece of code to handle all of it. It was fairly elegant, because it used something called a jump table, which meant that for each segment you could have a custom piece or it could use the same piece as something else. By putting all those together, we achieved some economies of scale. The name we ultimately gave it came from the Watts riots in L.A., as covered by Life magazine. I believe one of the headlines was ‘Burn, Baby, Burn,’ because that was something that was shouted by the rioters. Feeling a little bit fresh, we took that as the name of that routine, because it was about burning the engine, lighting up the engine.

MDJ: In order to accomplish that task, you needed to know intimately what the steps were—how to get there, what was happening, bubbles in gas tanks and so forth—and, in a strange way, know the aircraft, because the astronauts also knew that spacecraft incredibly well. They had to, right?

DE: Well, they were essentially generalists. They are not trustworthy, these days at least, on the real details. They were focused on what they needed to know to fly and to save their butts if something went wrong. Beyond that, they didn’t know the intricacies. Practically every technical explanation I’ve ever read from an astronaut is wrong, when it gets down to the code. Buzz Aldrin still doesn’t understand exactly what caused the alarms on Apollo 11!

MDJ: This brings in the other person that I met during that time at MIT, who became a friend. I found a lot of inspiration in reading David Mindell’s Digital Apollo [2008], which was about the thinking around the concept of feedback between humans and computers, and the concept that the astronauts were flying this vehicle. I was super-interested in the things that were built into that machine to make the astronauts feel more at home as humans in the cockpit flying that thing. When you’re talking about Aldrin not really fully understanding what was happening, how much of that lack of understanding do you think was actually not wanting to know?

DE: You know, astronauts are also storytellers. I think you can say that about pilots in general. They have a reputation for saying, ‘Oh, I shot down 15 airplanes,’ when it was really one confirmed. They have to speak to so many people, so they have the right to their stories, and we ought not to hold them to real technical accuracy, I think. There’s the Apollo 14 story about me being asleep and an Air Force car pulling into my driveway and someone pounding on my door and me putting a bathrobe over my pajamas and being rushed to the lab and told, ‘Solve this problem!’ That’s another one of those tall tales. But until recently, Dave Scott, the commander of Apollo 14, still believed it. I finally had occasion to talk him out of it. I don’t think he tells it anymore. But people love these stories. To some extent, I don’t mind.

Matthew Day Jackson, August 8, 1969, 2010 © Matthew Day Jackson

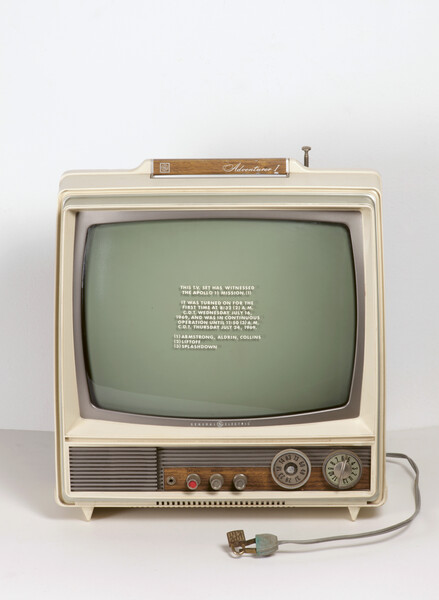

Siah Armajani, Moon Landing, 1969; stenciled television, lock, ink on five double-sided sheets of newspaper. Courtesy the artist and Rossi & Rossi

MDJ: There’s so much in our culture about astronauts being special, because they somehow exemplify our myths and beliefs. To a certain degree, we expect from them those stories. We expect them to reinforce that idea. That’s what’s so interesting about you and your job in relation to this—what you did is largely not understandable to most people.

DE: A little bit arcane. But the civilization is slowly growing into it. Kids learn software in school now. It will become more and more accessible. Back then, software was still being spelled S-O-F-T-W-E-A-R as often as not.

MDJ: We’ve all heard a million times that the Apollo Guidance Computer had the processing power of a Texas Instruments calculator; that was definitely part of what I was drawn to. But then I learned more about the so-called ‘little old ladies’ who actually hand-wove the computer [specialized seamstresses at Raytheon in Waltham, Massachusetts, threaded copper wires through magnetic rings to form the computer’s memory banks]. It’s like the finest jewelry you could ever imagine in this unbelievably exquisite machine. It was amazing to see the computer when I first went to MIT, whose collection has bits and parts of the thing—what it physically looked like and felt like, and understanding that this thing was entirely handmade. Also, the program that went into the thing was totally custom built. From a sculptor’s perspective, it’s like…whoa.

DE: There was no sense of opposition between what the man was doing and what the machine was doing, because both were needed. A man couldn’t fly that trajectory in a fuel-efficient way without the help of the computer. But there would be no way of landing at a specific spot on the moon without the man. His eyes and his judgment during that last couple of minutes coming down to the moon were absolutely vital. That same mission could not have been safely completed automatically.

MDJ: When I was at MIT, I had tried to talk them into allowing me to put my naked body into their wind tunnel, which is named after the Wright Brothers, then have them turn it up to 160 miles an hour to roughly approximate the feeling of falling at terminal velocity through low Earth atmosphere. I wanted to have the experience of falling, but I didn’t want to actually be falling. I could have jumped out of an airplane, but to record my experience that way would have been be difficult. I wanted the experience to be recorded without affectation. So I wanted the camera to film how I was reacting to this situation without the camera falling as well. I didn’t want the viewer to be falling with me. I wanted to have an illusion of agency, which was inspired by that idea that there is a computerized system that is fundamental to making such an illusion possible—in testing airplanes, aerodynamics, all of it. But I also wanted to have the immediate reaction of a human being looking at where he’s going and telling the machine what to do—how these things need to work in conjunction with one another. I’m not interested in the technical part; I’m interested in what it means. You’ve had a long time to think about your part in this and how important this narrative is in our culture. There are always two benchmarks for a nation to express its value…

DE: War and exploration?

MDJ: Totally. Nuclear capability and space travel. Those are really the pinnacle of expressing power in the world.

DE: We’ve drawn back from it, or at least in this country—we landed on the moon 50 years ago and haven’t gone as far as that since.

MDJ: Way back. What, like, only 120 miles away from Earth’s surface?

‘I think the moon-landing images were…frightening for people. It felt like civilization was sticking its neck out when we did that, and people maybe became afraid…and so they have gone back to the more familiar area of war as a way of expressing power.’ —Don Eyles

DE: I sometimes wonder if those images of landing on the moon were more frightening than we think. The 9/11 images, for instance—I don’t think there’s any question that that’s one of the reasons why this country has acted spasmodically since then in its foreign policy and other ways. And witness what’s happening now, politically. But I think the moon-landing images were also frightening for people. It felt like civilization was sticking its neck out when we did that, and people maybe became afraid of that, and so they have gone back to the more familiar area of war as a way of expressing power.

MDJ: I think it’s not necessarily the images of the surface of the moon or images of a human being on the moon, but rather it’s the pictures looking back, that image of the ‘earthrise’ that was on the cover of the Whole Earth Catalog, that showed the totality of every single thing that we’ve ever known and experienced.

DE: You’d think logically that seeing that would have the opposite effect. That it would have made us more responsible and given us more of a sense of togetherness on earth.

MDJ: I think for a lot of people, those images did have that effect but maybe not for enough. You know, I’d like to go back for a second, to your history: you applied to the famous Draper Lab, which was then at MIT, as a summer job? [The lab, founded in 1932 by Charles Stark ‘Doc’ Draper (1901–87), has played a pivotal role in developments for commercial and military aircraft, weapons systems and spacecraft.]

DE: It was summer, but I was applying for a full-time job.

MDJ: The way that it’s been told to me was that it wasn’t as purposeful. You weren’t going there because you knew what was being undertaken.

DE: That’s somewhat true. I needed a job. I would have taken just about anything that had been offered to me. I’d just been to an interview for what I’m sure would have been a deadly dull job working for some company. I happened to walk by the lab on my way home. Maybe it was intentional, maybe it wasn’t. I saw the sign on the door, took a deep breath, and went in. It happened very quickly after that. They were hiring wholesale. I was a not very illustrious mathematics graduate. The guy who interviewed me said, ‘I’ve even hired literature majors.’ I think the fact that I said, ‘Well, I can always be a technical writer,’ may have entered into it, because that’s always hard to get people to do. Fortunately, I escaped that. I was at the right place and the right time, which continued when I was assigned to work on the lunar landing, because that was, by far, the most complex but also the most interesting part of the mission. It’s the thing that led to all my interesting experiences. The lunar module was a new vehicle, a truly experimental vehicle that no one fully understood.

MDJ: I’ve been very lucky to meet a lot of really remarkable people, but you’re the weirdest one, because you’re also an artist. Were you making art back then, too?

DE: I was doing some photography. I don’t draw a hard line between art and technology, or art and engineering. I think they’re very parallel, if not the same thing practically. I mean, the motivation may be different. I’m not talking about painting nudes, for example, which I know nothing about. Maybe there’s not much relationship between painting the body and engineering a space project. But for lots of kinds of art, I think there is a parallel, in the sense that there’s a period of time where you’re trying to design and fabricate the thing—whatever it is, the sculpture. Then, there’s a moment when it goes out into the world. And if it’s a spacecraft, that’s the launch, and it has its mission. If it’s a floating sculpture, like some of the stuff I’m doing in Boston, then it goes into the water, and that’s a harsh environment. Sooner or later, something is going to happen, and you don’t know what. Once you’ve made it, it goes out into the world and it has a history.

Matthew Day Jackson, The Tomb, 2010 © Matthew Day Jackson

MDJ: There is a tremendous amount of responsibility in the systems work you did. It’s very different from making art. Art has a lot of responsibilities, but not ones in which there are two people inside an object in outer space who need to land safely and come back home.

DE: You know, like they say, young soldiers are braver because they don’t know enough to be afraid. The way we expressed our responsibility was to try to think of everything and to be intellectually honest about it—to never write off a problem because we thought it was too small. If it was something we didn’t totally understand, we would make an effort to understand. We knew we wouldn’t think of everything. There was always going to be something, but we thought we’d be in a better position to deal with that something when it did occur.

MDJ: I think about how the astronauts—after going that far and doing this incredible thing—must feel about the rest of their time on Earth. As an artist, you make a thing and then all of your time is spent trying to better it. There’s always the pursuit of personal best, that tiny space just beyond what you’ve accomplished. That space can be infinitely far away until you’ve started to hedge into it. How is that time for you still mined? Because you’re one of the most deeply curious people in my life. How is that hunger satisfied?

DE: Well, there’s one space project and then there’s another one, and you have to stop thinking about the previous one when you go onto the next one. I still look back and say, ‘Well, gee, why didn’t we do it this way? That way would solve that problem.’ But so much of that is hindsight, and it’s fairly unproductive because I was moving on and working on the space station or the Space Shuttle. You know, I wrote software that’s still running right now in orbit. The second exciting phase of my career as a rocket scientist was at the end, in the ’90s.

MDJ: There’s an important aspect that I don’t think is understood about what you and your colleagues did—that it wasn’t just landing somebody on the moon and creating a different way of thinking about how human beings traveled in a machine, but it was also creating a different way in thinking about computing itself. The whole thing was new. Totally made up.

DE: That’s true. The toolmakers, the pioneers who came before me, are the real unsung story. People like Hal Laning, for example, who created the operating system that figured in so many of the stories, especially Apollo 11 and its ability to keep going even though there was a serious problem happening. [J. Halcombe Laning (1920–2012) developed the first algebraic compiler, which became the forerunner of important programming language such as Fortran]. And then I came along as the upper layer, maybe the more glamorous layer—the code that sits on top that has to do with actual phases of the mission, which was a lot more fun probably than creating the actual tools, but it couldn’t have been done without them.

MDJ: It’s like the astronauts are flying the spacecraft, but you’re flying the computer, right? That’s what the programmer is doing; you’re making it so that a human can make the thing operate. That’s really interesting to me. I think of it in relation to what we’re experiencing now, where we have cell phones that connect to social media so that I can tell people that I’m eating key lime pie at 2 a.m. on a Tuesday or some stupid thing. But the machine that you worked on had to be extraordinarily economic in its design and manufacture because of the limits of what was known at that time and what could be accomplished with magnets and wires woven around each other. And it had to work for relatively untrained operators to fly with seeming fluency. Right?

DE: I think that’s fair to say.

MDJ: Mindell, in his book, argues that it is still fundamentally important that we have human beings exploring space because it is our direct experience that brings back to the people of Earth the awareness of ourselves in relationship to the thing that we’re exploring. But I think most of what’s happening now with space exploration is an illusion. It’s not a real experience. We’re just recording the thing that we should be experiencing. We’ve even left the responsibility of taking stuff up to our own space station in the hands of private individuals.

DE: But that’s a good thing!

MDJ: I see it as a total bankruptcy of everything.

DE: But if we can have cheap transporta tion into Earth orbit, that’s an enabler for all sorts of exciting things. We know we can assemble things in Earth orbit. It really opens the door to the imagination because, instead of designing a grand system that lifts off from the Earth, like Apollo, we can decouple different parts of the mission. We can have one organization that creates a ferryboat that can take us from Earth orbit to lunar orbit, and some other organization can take over the part that goes from lunar orbit down to the moon, and somebody else, the part that would go to Mars.

MDJ: It isn’t a problem for you if it’s private industry that’s doing it?

DE: No, not really. And in terms of a political decision, I think Obama, who’s blamed for that, had no choice. Was he going to bust his budget in order to fulfill grandiose promises that Bush had made? Or was he going to say, as he did, that now is the time to step back a little bit? Earth orbit travel is something that private industry can handle, and we’re about to get to the point where you’ll be able to launch stuff into Earth orbit on SpaceX or Boeing’s system relatively cheaply.

Heidi Neilson, Moon Arrow, 2018, Fort Totten, Queens, New York. Photo: Heidi Neilson

Scott Reeder, Moon Dust set, installed at 365 Mission Gallery, L. A., 2014. Courtesy the artist and Kavi Gupta. Photo: Joshua White

MDJ: Yeah, I don’t know. I feel there’s something weird about it…

DE: It’s better if the government does it? Well, if the government would do it.

MDJ: I think about the good parts of the technology that got us to the moon, the parts that were for everybody and that have helped us as a species. But now that kind of technology—which was once for everybody, like a public resource—is being funneled through private industry, where it will become proprietary, purely for profit.

DE: Oh, I see.

MDJ: Maybe I’m wrong. I’m just an artist. [Laughs] But it seems like we’re giving it away to them. And then we’ll be paying rent, like Uber. Uber rides to the space station.

DE: But it’s easy to get to Earth orbit. The government doesn’t need to be the one that does it. If our entire system were government run and there was no private industry, maybe, but I see privatization for that part of it as an enabler rather than as something being lost. I think it’ll free up our thinking a little bit—once we have the ability to go into Earth orbit cheaply.

MDJ: Who’s going to be doing that?

DE: Good question. Who will take it the next step? I hope the government will still be deeply involved. Without NASA’s help, SpaceX and Boeing and so on wouldn’t have succeeded. We had a fairly lean program on Apollo, but the government space program has gotten a lot less lean since then. There are a lot more people working at NASA, yet the missions are a lot less ambitious. If you can let somebody like Musk organize the effort for the basic stuff, it can probably be done in a more lean and efficient way and give the government leeway to do more with its resources. The results have been pretty impressive so far.

MDJ: I don’t know…

DE: I always want to be an optimist, of course. The place where I’m a pessimist is about certain other trends happening in the world—the fact that by being brought closer together in the global village, religions, for example, are causing more conflict that they used to. Not to mention the environmental crisis. All those trends, I think, are terribly dangerous, and they can’t continue the way they are now. Within all of that, I actually see space flight as a bright spot, with synergies with all those problems. But it will take some will to put those synergies together, and where that effort’s going to come from, I don’t know. It's maybe the government’s role or the role of a great leader to put that together, to make people enthusiastic about it the way Kennedy did about going to the moon.

MDJ: How old were you when you started working for Draper Lab?

DE: Twenty-three.

MDJ: How many other 23-year-olds were there?

DE: A few. Peter Adler, whom I’ve mentioned, was my age and was hired at about the same time.

MDJ: It’s my understanding that there was a clear generational division at Draper Lab. Do you think the fact that your generation, in the ’60s, was a lot more open to chance played a role in what you accomplished? To me, now, looking back from another generation, it seems like it couldn’t have happened at any other time.

DE: I agree with that, but part of it was the fact that there weren’t very many suits where I was. We were an academic lab that had the capability to do this—really the only ones at the time who could’ve done it. And I think our suits—our management structure—understood that the only way this was going to happen was if they trusted the youngsters like us. I think our managers at the lab, at MIT, saw it as part of their duty to protect us from the suits at NASA, if you want to put it that way. It was a structure originated by Doc Draper, who founded the lab and who was trying to create an Athenian democracy, as he put it, where talent would rise to the top.

‘The moon is ultimately not that interesting. It’s like a barren lot strewn with junk out behind a factory somewhere.…But it’s a stepping stone.’ —Don Eyles

MDJ: All these years later, do you see any darkness, so to speak, in what you all accomplished?

DE: The darkness is that it feels like a lot of the work we did was wasted, in that it wasn’t followed up on—in that, we have retreated to such a degree in space. You know, I would not have believed, in 1972, that even 20 years would go by and we wouldn’t be on Mars. And now 50 years have gone by, and it’s not likely to happen any time soon. It seemed like this beautiful system had been put together. We had learned so much. Going to Mars didn’t seem like much more than just needing more fuel. The guidance problem wasn’t so different. You would’ve needed to construct the Mars ship in Earth orbit, using two or three Saturn V launches to put the materials into orbit. But we could’ve learned, then, the same on-orbit construction techniques that we later used for the space station. There really was no obstacle except money and national will. We already had the Skylab project queued up at that point, and that was going to teach us a lot about long-duration stays in zero G. So everything was in place.

MDJ: The thing I always get caught up on is this: What do you do on the moon? What is it about the moon? It’s not necessarily that we were going there to learn about the moon; we were going there to learn that we could go there. That’s one of the problems with how we explore our environment—which includes the moon and now outside of our solar system, as Voyager beeps its faint little beeps. It seems like we’re not really exploring the thing as much as we’re exploring ourselves and what we can accomplish with a machine to get there.

DE: I think that’s true. The moon is ultimately not that interesting. It’s like a barren lot strewn with junk out behind a factory somewhere. It’s not that attractive a place. But it’s a stepping stone, and it’s not as deep a gravity well as Earth, so it’s going to be a really useful place for some technical purposes. You could also question the interest in Mars, but I predict that we will eventually find life on Mars, primitive life, and perhaps in some other niches in the solar system as well. That’s very exciting. I think that if you believe there’s any sort of destiny for mankind to keep exploring, then you have to go by way of the moon; it’s the next place you can reach. I don’t try to make predictions, but it seems like, within the next century or so, we ought to be able to explore the solar system pretty well, and taking humans, at least to get to the vicinity of Saturn and Jupiter. Whether it will really be possible to land on Titan, I don’t know, but it would be an interesting problem. And then, of course, the next really big jump is to try to go out into interstellar space, but it’s hard to imagine how we would ever get to that point. There are limitations of the speed of light and so forth.

MDJ: And our human bodies. Have you ever heard Werner Herzog talk about space travel?

DE: I don’t think so.

MDJ: I can’t quote him, but he’s basically saying, stop with the space nonsense. That’s not an argument that I’d make, but in thinking about how we aren’t fundamentally interested in the moon or in Mars, that we’re more interested in our ability to get there, I see his point. Maybe getting to the moon and to Mars is about the fact that we have to accomplish that step first, to understand what we’re doing, in order to go beyond and learn more. But maybe our interest in getting to those places, just to see if we can do it, is a limitation of our humanness, a result of our self-absorption.

DE: To me it’s the first thing you said: think universally, act locally. All we can do now is go to the moon and maybe to Mars, before too long.

Installation view, ‘Tom Sachs. Space Program’, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA, 2007. Photo: Josh White

Aleksandra Mir, First Woman on the Moon, 1999, produced by Casco Projects, Wijk aan Zee, NL. Courtesy the artist

MDJ: In being an artist, I’ve always felt that nothing’s ever been done before. Nothing. The way that you step out to go to the grocery store to buy an apple is always different, even if you tried to perfectly replicate it.

DE: Everything’s decaying all the time. Everything is in motion all the time.

MDJ: If I believe that nothing’s been done before, then that means everything is original. So why get hung up on this idea that there’s this original author that’s doing this thing, that astronauts have conquered this goal that we don’t need to accomplish again…

DE: The enduring thing we’re making is the story. I just re-read The Iliad, a great epic. Cumulatively, all the stories out of the space program are sort of the same way. In a way, I feel more proud about writing my book than I do about the work I did in the ’60s and ’70s because I didn’t have to write the book. I wasn’t being paid to write the book. It was a story that I felt needed to be told, one that I felt I was in a unique position to tell, that I hope endures. It’s of little consequence that Troy fell to the Greeks in whatever year it was, but the story is very important to our civilization.

MDJ: As an artist, I don’t believe that I own anything. I’m merely a caretaker for art at this moment in time, keeping it alive, to a certain degree, for somebody else later.

DE: I think it’s more than that. You’re constantly experimenting and you don’t necessarily know what’s going to come out of the experiment.

MDJ: Of course, I’m not saying that authorship is the least important part. I think that we are shepherds. For instance, we’re moving into the 50th anniversary of this event, and I think that we’re all trying to make sense of this thing, but I hope that we think about it more from a philosophical standpoint, rather than just look back to this great moment. I wasn’t alive then—I was born in 1974—and so this thing for me has always been a story. It’s always been tied to a number of other narratives that are also fundamentally important, like the civil rights movement. It’s like, we can land people on the moon, but we’re still stuck in so many other repetitive cycles we can’t solve. Can an event like this 50th anniversary remind us of our duty, which is much greater than ourselves, to be the shepherds moving these things forward? That’s the point that I’m trying to make in my work—by having these images persist, as an artwork, in the time that I’m living in, and not letting them fade into the past. I think it’s better than simply giving a history lesson. In writing your book and telling your story in relationship to this event, what do you hope for?

DE: Like a legacy?

MDJ: Yeah. When I said to myself, ‘I want to be an artist,’ art showed up and was like, ‘Hey, here’s everything. Do with it as you will.’ So, to a certain degree, in making the things that I make, I want them to be everybody’s. What do you want to accomplish with your book?

DE: I want kids to read it. I want something about the excitement at that time to come through. I want to tell a good story. I want it to be read for pleasure. In my plan for the book, I wanted to make a connection between fine details—a line of code here—and a historical event there. I also wanted to say something about the times, about the milieu we were in and what I was experiencing as a youngster. I never pretended to be typical. I was eclectic. And so by bringing in some of those various things about my life, I felt that I was adding to the story of going to the moon. So yes, I’d like to influence the future. In 500 years, people may not even believe we went to the moon. Maybe the hoaxer narrative will be so strong at that point people won’t even accept the facts. If my book helps with that, too, I don’t mind.

MDJ: Just the idea that flat-earth hoaxers would somehow prevail is…

DE: It drives me crazy. I try to be polite to them to begin with, but pretty soon I get to the point of saying, ‘You’re just ignorant.’

MDJ: I think there are a lot of things that we take on faith, and what it boils down oftentimes is, what’s more fun to believe in? Even if it’s totally outlandish, well, it’s more fun.

DE: When you’re reading history, remember that, because history is written by the winners.

MDJ: The moon moves oceans, right? The gravitational pull of the moon moves ocean tides. And as long as there have been eyeballs on earth, people have looked up to the moon and thought of it in mystery. It’s fundamental in religion and mythology and all these things…

DE: I doubt it’s a coincidence that the lunar period coincides with the menstrual period of women.

MDJ: Do you think our space exploration or moon missions reduced any of the valuable mystery of looking up and thinking about what surrounds us?

DE: There will always be another mystery. What if we did kill it? The mystery was part of our motivation. It’s exciting to see what the next memory is, what the next mystery is, even if you’ve solved this one. The first solution to the elements was earth, air, fire and water. That was great.

‘I mean, I would love to hear Buzz Aldrin talk about his feelings.’ —Matthew Day Jackson

MDJ: When you were in conversation with friends while you were working on the landing, did you talk about how, you know, if you missed, there would be some well-preserved corpses in tin cans floating around above us forever and ever?

DE: We realized that there were certain situations that could put the spacecraft into a solar orbit, and you’d never get back from that. But you did your best to do everything you possibly could to make sure that didn’t happen. More likely would be to lose your way all the way at the very end and hit the Earth’s atmosphere wrong coming back. Until we saw the parachutes from Apollo 13, for example, we didn’t know whether the crew had perished. I guess we knew at that point that they hit the atmosphere right, but we didn’t know whether their spacecraft was damaged. The silence lasted longer than it should have. But I think that was the same moment in which the astronauts themselves realized they were still alive, after 87 hours of getting sicker and sicker in a cold spacecraft with water on the walls from the condensation and virtually everything turned off. They didn’t know whether they were already dead.

MDJ: There are those things—like fear of death, or fear of the unknown, or fear of missing your mark—that aren’t really talked about in many of these narratives about the space program. I like to think about the humanity of it—that we are fallible, that there are things that we don’t know, that there’s an emotional resonance left over from doing what astronauts did. For me, telling it as a kind of dominant narrative makes it like a superhero story; it flattens out the experience. I mean, I would love to hear Buzz Aldrin talk about his feelings. To dismantle a portion of how that story is told would actually lead to a deeper investigation and make the experience more real, more relatable, to people.

DE: The inner story of the 87 hours when you may be dead already. How do you tell that story?

MDJ: Well, there was the Tom Hanks movie.

DE: Apollo 13 was a pretty good movie, but for dramatic effect they exaggerated the explosion and the crisis of the maneuvers they had to make; they were shown as much more violent and noisy than they were. How could they convey the utter depths of despair that three people were probably feeling at times?

MDJ: If the movie had been made with small explosions and mostly silence, it would probably have been much more horrifying.

DE: Right. The astronauts actually heard what they described as a dull thump.

MDJ: We should remake it. The best horror films are the ones where almost nothing happens.

DE: I always wondered if you could put that on the stage. Could you do Apollo 13 and explore some of these vulnerability issues? I mean, you can’t have an 87-hour play. Nobody would watch it…

MDJ: In art, sure you could. You could have a durational performance!

DE: Okay then. We could have a space craft and maybe some pieces of it come off so you can see the people inside and it hangs from the ceiling and you show maneuvers and so on. Or would so much technology in the production take away from what we were trying to do? All the dialogue exists, you know? It was all recorded. You have a basic script.

MDJ: I know. It would be like a durational Kabuki performance of Apollo 13, in which a lot of what happened was just waiting and silence and dread. Part of the performance would be that the audience would have to eat exactly what the astronauts ate, to create empathy. We could give everybody in the audience space diapers so that they could sit through the whole thing. 87 hours without going to the bathroom! I think we should do this.