Conversations

A conversation between Matthew Day Jackson and Dea Vanagan

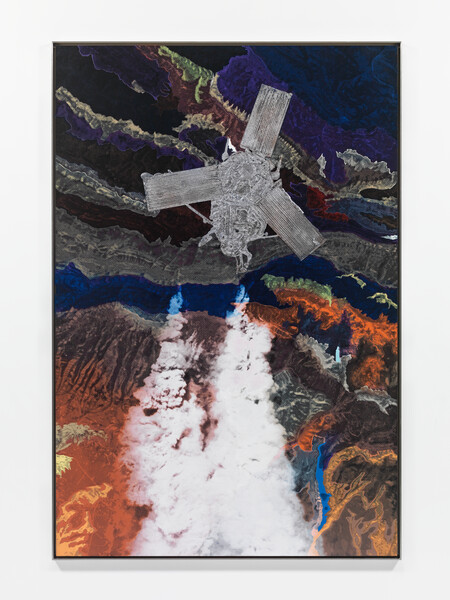

Matthew Day Jackson, Solipsist XXI, 2018 © Matthew Day Jackson

- 14 January 2019

Dea Vanagan is a Director in Somerset, and part of the team responsible for exhibitions, events and artist residencies at the space. Dea worked closely with Matthew Day Jackson on his recent exhibition in Somerset.

Dea Vanagan: You’ve said that art happens outside the studio, and that you find inspiration in where you are at any given time, as in your surrounding environment—can you talk about this in relation to how the Solipsist works came about?

Matthew Day Jackson: A long time ago, I watched Werner Herzog’s film about the end of the first Gulf War, in which retreating forces set the oil fields of Kuwait in flames. For whatever reason, I found aerial images of those fires taken from a satellite several months before my visit to Somerset. My first day in Somerset, I followed a ‘green lane,’ on my bike—which was a road, then a gravel road, then a fence, then a path, then cow trail, then nothing, then forest, while always being a ‘green lane.’ This trail led past a Bronze Age habitation and finished at King Alfred’s Tower (a folly erected in 1772). It was like taking a time machine, seeing human traces from the present to 5,000 years ago. So the aerial photographs—showing our engagement with earth on a macro scale—led to finding other events showing landscapes altered by human intervention. These two things really framed my residency and became the foundation for the exhibition, ‘Pathetic Fallacy’.

DV: A wonderful quality of your work is its ability to be appreciated aesthetically from first encounter, yet also with great intellectual rigor referencing ecology, politics, and art history. What were you looking at in the development of these works?

MDJ: A lot of images of satellites and astronaut photography. The rest of the time, I am simply trying to pay thebest attention I can to my surroundings and the people I meet. I know this sounds hokey, but we all have an intelligence, which is preverbal, that guides us to people we love and to our interests and passions. I am trying to let that part do more work because it seems if it were a muscle, it would quickly atrophy in the face of the technology with which we interface daily.

DV: How did you select the geographical locations?

MDJ: The locations were selected through hours of looking at astronaut photography and I was fascinated by what they thought was interesting. I found very few images looking out into space—it seemed they were unanimously interested in looking back at earth. So, with that, Solipsists were born in the seemingly incessant need to photograph earth and see ourselves in relation to the world around us, to offer self-reflection.

‘For me everything is handmade. I am primarily interested in the resolution of what is being made from the crude to machine perfection.’

DV: There are so many unconventional materials and a myriad of skills employed in a single work, yet a complete harmony in the final image.

MDJ: I am in love with how well seemingly disparate materials can come together. Formica—which is a trademark, but interestingly, also the slang term for ‘high pressure laminate’—has been a material that I have been using for years. I am now making a custom laminate based on aerial views of the far side of the moon with Formica! Formica is a material that comes from anywhere trying to be something else. The surface is familiar, and whether it be ‘stone‘ or ‘wood,’ it never reveals its true material—which is paper and epoxy. Representing earth in this material speaks to our lack of concern or understanding of its surface.

DV: For me, the surface texture of the Solipsists are most surprising. At first glance, your eyes don’t compute the complexity of what you’re looking at, but then you notice the series of layers and the handmade human element in everything: the sculpted satellite reliefs made of poured molten lead, the assembled jigsaw of Formica as earth, and the worked-in paint using a scrim depicting smoke, coupled with more traditional processes of silk-screening and etching. Is evidence of the handmade important to you?

MDJ: For me everything is handmade. I am primarily interested in the resolution of what is being made from the crude to machine perfection. The range of resolution creates a complexity that I find exciting. I love Van Eyck because of the range of ‘resolution‘ in the work and the way in which flesh or gold comes alive. For the true magic of the handmade, Van Eyck is a good example—he made the actual material of gold unimportant through creating a painted illusion of gold.

DV: I love reminding people entering your exhibition that you were trained as a printmaker, as it allows for a unique angle from which to interrogate your works. How do you think printmaking influences your approach to art-making and your overall practice?

MDJ: I have always said that one can make a great print while also making bad art, in other words, ‘good at process, bad at images.‘ I saw printmaking early on in my education as a way to measure success.

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Iwan and Manuela Wirth in Matthew Day Jackson’s exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Somerset © Matthew Day Jackson. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

Oudolf Field at Hauser & Wirth Somerset. Photo: Jason Ingram

DV: From a technical viewpoint?

MDJ: Yes, as I could be told I was doing a ‘good job.’ Process was a way to eliminate my hands while being entirely dependent upon them. Printmaking forces the hand away from the finished work while re-gaining an excellent relationship with one’s hands. My hands are in service to my ideas, and when I was a printer, my hands were in service to other artists’ ideas where it was important that they were never visible in the finished work.

DV: Something you keep returning to is that as a family, you are ‘good at being where you are,‘ and I understand that as ‘being present.‘ How do you want people to interact with your work?

MDJ: I want people to enter the exhibition thinking about ‘flat earth’ and the rules of engagement, not with the land, but with each other.

DV: What do you mean by ‘flat’?

MDJ: I am referring to our tendency to document, to surveil, to map as a way of totally occupying earth, not just in the physical sense but through images, and a desire to know everything and the conceit to think we could handle it. I see the satellites through the lens of Paul Virilio’s concept of Total Accomplishment, which was about the progression of the development of the camera, the gun and the flying machine toward the total occupation of earth and space. I see the satellite not as a machine absorbing information, but more as a machine that illuminates earth. I like thinking about the satellite in this way, as it makes me imagine a sphere evenly lit creating a flat disc without shadows.

DV: Which is very fitting, as you seem to have an insatiable appetite and memory for learning new skills and finding connections. How do you go about clarifying the plethora of ideas?

MDJ: When I allow myself the space to be inspired by things seemingly incongruent with existing concepts, it makes me available to new ideas.

DV: Throughout your time in Somerset, the concept of pathetic fallacy—describing the attribution of human emotions onto inanimate objects in nature—served as a potent tool in your continued investigation into how we understand our natural world.

MDJ: We see our emotional selves in weather, and our corporeal body in the soil and seas.

Installation view, Matthew Day Jackson, Pathetic Fallacy, Hauser & Wirth Somerset Bruton, UK, 2019 © Matthew Day Jackson. Photo: Ken Adlard

Matthew Day Jackson at his studio in residency at Hauser & Wirth Somerset. Photo: Clare Walsh

DV: I know it’s a notion that you’ve been exploring for a long time, but you found clarity during your residency in Somerset. Why do you think that is?

MDJ: All of my time has been spent in the United States, where a relationship to landscape is one that is religious and without the same traces as those in the UK. I know that people have been living in the United States for at least 15,000 years, but most of this inhabitation is without a trace or knowledge for most Americans—myself included. I think being in a new place forced me to find familiar things to make it less threatening. Seeing human intervention everywhere was really startling and comforting in a way I had not previously experienced.

DV: Why did you want to do the residency in Somerset?

MDJ: Hauser & Wirth Somerset is the place where a great many things happen that I closely associate with the DNA of the gallery and the things I love about it. We also saw a unique opportunity to experience a new place with our family and with our practices.

DV: How was it settling into a new studio for five months, and how did that change your approach, or did it?

MDJ: It was only difficult at first, which was more about getting everyone settled, like any trip. Otherwise, the studio was totally set up for us to get straight to work and we were well taken care of—like a sacrificial animal. I joked that they were going to sacrifice me at the opening.

DV: Maybe at the finessage! [laughing] Looking back to the residency, what has been its lasting impressions or impact in your work or life?

MDJ: I met many people whom I love, and with whom I will be friends for a long time. I learned how little sleep I can get while still being alive. I learned to run for long distances (for me). Most of all, I saw my family do what it does best, being together and experiencing something new. Our boys were our best diplomats for who we are as a family and seeing them negotiate this experience was deeply rewarding.

‘Solipsist XII’ by Matthew Day Jackson is part of Hauser & Wirth’s presentation at Art Basel, from 13 – 16 June 2019.