Conversations

Making Doors: Linda Goode Bryant in Conversation with Senga Nengudi

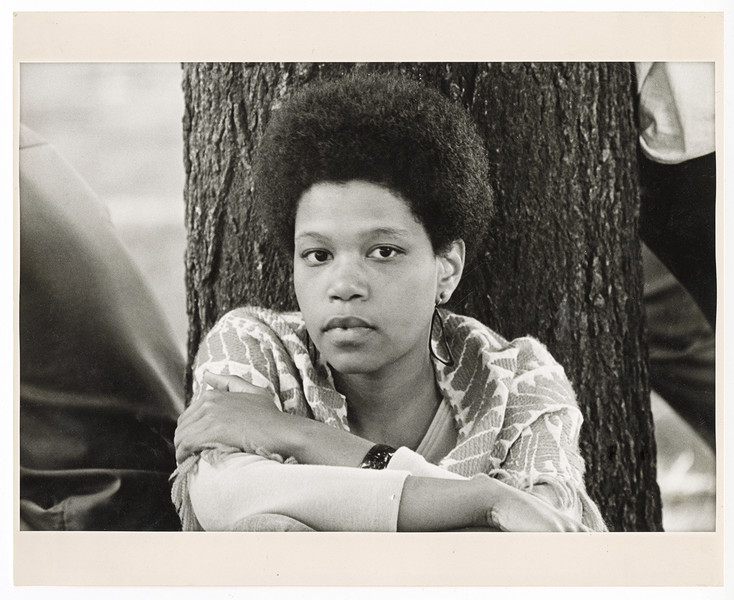

Linda Goode Bryant. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

The artist Lorraine O’Grady once wrote about the joys of a ‘unique art-making moment, one when the enabling audience—the audience which allows the work to come into existence and to which the work speaks—and the audience that consumes the work are one in the same.’

For many artists in the 1970s in New York, such grace moments were possible because the art world itself was still small and the audiences for work on either side of the equation were likewise limited, sometimes distressingly so. For artists of color, however, the situation was dire, as it had always been. These artists were generally ignored not only by commercial galleries and museums, but even by most nonprofit art spaces. And institutions that would begin to change the landscape, like the Studio Museum in Harlem and El Museo del Barrio, were still young.

In 1974, Linda Goode Bryant, a Columbus, Ohio, native who had come to New York for grad school and worked briefly at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Studio Museum, decided to do something for the African-American artists she knew, and the ones she wanted to know: She founded a commercial gallery—which she called Just Above Midtown, or JAM—smack in the heart of the old-guard art establishment on West 57th Street, the only black-owned gallery of its kind in the city. During its 12-year existence, uptown and after a move to TriBeCa, JAM was a tireless, boldly experimental pioneer, one whose impact is still far too little acknowledged in the history of the 1970s and 1980s contemporary art world. It showed the early work of many African-American artists who have gone on to great renown: Lorna Simpson, Senga Nengudi, David Hammons, O’Grady and Fred Wilson, to name only a few.

By the mid-’80s Bryant had grown disillusioned with the art world and the increasing power of money within it and she left it to pursue filmmaking. Flag Wars, her award-winning 2003 documentary, co-produced with Laura Poitras, examined the complex politics of a working-class black neighborhood in Bryant’s hometown, Columbus, during a period in which it was being gentrified by gay white homebuyers. In 2003, while documenting the run-up to the presidential election for another film, Bryant became convinced that she needed to move more fully into the realm of activism. She founded the nonprofit Active Citizen Project, a youth-focused initiative that encourages the use of art and new media as tools for social change; by 2008, the organization led to the creation of Project EATS, a network of urban farms across New York City whose goal is to help residents of economically challenged neighborhoods eat healthier and have greater control over their food supply, stimulating job creation and community-building.

Bryant’s catalyzing role in the art world is highlighted in ‘Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,’ a sweeping survey of African-American art from the 1960s through the early 1980s, which remains on view at the Brooklyn Museum through February 3, 2019.

The following conversation between Bryant and Nengudi was recorded in Bryant’s Upper West Side apartment one morning in the summer of 2018. When I arrived, the two friends, longtime tennis fans, were watching an episode of the HBO documentary Being Serena, about Serena Williams’ struggle to balance motherhood and professional tennis. — Randy Kennedy

Senga Nengudi performing ‘Air Propo’ at Just Above Midtown in New York, 1981. Courtesy Senga Nengudi and Lévy Gorvy gallery

Randy Kennedy: We can start wherever. We could just talk about Serena Williams all morning if you want. But I’m wondering when the two of you first met each other.

Linda Goode Bryant: Senga and I have known each other since ’76, right around there. I always tell this story, and I’m sure Senga thinks, Why does she tell this story? I think that Senga and I were destined to meet. I was a single mom and had two babies, a three-year-old and an infant. I came to New York when my daughter was three weeks old. I didn’t know anybody. I’d graduated from Spelman College in Atlanta, and I’d been accepted at City College. I had always, since the age of four or five—because of Shirley Temple, quite frankly—wanted to live in New York. I would say to myself or say to God, ‘God, I don’t know why you made me here, because I’m supposed to be in New York City.’ My parents said I would look at a Shirley Temple movie and turn around and say to them, ‘When I grow up, I’m gonna live in New York City. I’m gonna have eight rooms, river view!’

Senga Nengudi: [Laughs] Well, you didn’t exactly get that river view when you came here, did you?

LGB: No, I didn’t. I lived on 80th between Columbus and Amsterdam. And shortly after I arrived that August of ’72, there was an article in The New York Times that said that block was the worst drug block in New York City. I didn’t think about where I was living; I just needed a furnished apartment, and I had just enough money to get it—$500. New York, no matter how it looked, was the magical place, the Land of Oz. By the way, Judy Garland was another one of my sheroes, along with Pippi Longstocking. Those three gals kept me going.

SN: So tell the story.

LGB: Right, so how does this tie to Senga? Central Park is the next block over from Columbus, and I would take my kids there. My son loved that block between Columbus and Amsterdam by the Museum of Natural History, because pigeons would cover the sidewalk. I’m crossing one day to go into the park, and this tall brother was crossing from the other side. I noticed him because he was tall. And as we’re getting closer to one another, he goes, ‘Sister, can I talk to you?’ And to myself I’m like, ‘What? I don’t know anybody in New York.’ And he goes, ‘Can I talk to you, beautiful sister?’ And I go, ‘Uh, yeah.’ He was really warm. I think something about him sensed I was by myself, and he goes, ‘I live in this house in Harlem, a bunch of us live there, and you should come live with us too, you and your babies.’ It was just the most generous thing. He said his name was René Pyatt.

SN: René was my significant other at the time. We were living together in Spanish Harlem, in a house that was a kind of a gathering place for artists, 243 East 118th Street, a brownstone that’s still there today. René, who’s no longer living, was an artist who was connected to the Weusi collective and gallery in Harlem, an African-American group that was part of the broader Black Art Movement and was formed in 1965 by artists who were focused mostly on African themes.

LGB: I never did take René up on his offer to live in the house, and I never saw him again, but when Senga and I finally did meet—we met through David Hammons—it was like I knew we were supposed to be friends. Things kept putting us on the same path. And now we’ve been friends, and we’ve been having essentially this conversation you’re sitting in on, about art and everything else, for more than 40 years now. It’s a whole lot of life.

SN: I had come to New York at that time from Los Angeles, where I grew up, because I had a teacher who told me that if I really wanted to be a serious artist, I needed to go to ‘New York City boot camp.’ I was always in love with New York, the same way Linda was as a girl. I first came as a teenager, I think in ’61, and stayed with my cousin. We went to Macy’s, and I got all these wonderful clothes. She had a station wagon, and would you believe it, we stepped out of the car for one minute, and somebody stole everything! That was my introduction to the city. So I knew what I was getting into. If Linda was into Shirley Temple, I guess I was into Holly Golightly and Breakfast at Tiffany’s. I wanted that kind of New York apartment building, filled with a bunch of wild people, a bunch of misfit toys, and that’s what I got in that brownstone.

LGB: Correct me if I’m wrong, but you were doing work having to do with silhouettes when you were there, right?

SN: Right. I was working abstractly in Los Angeles, making pieces in which I sealed up water in heat-sealed plastic forms. I guess I felt a little intimidated in New York—where so much work being done by black artists tended toward the figural—to do what I’d been doing in L.A. So the silhouettes were the closest I thought I could get. They were made out of flag material, and I’d take them and hang them outside on the fire escape and let the wind kind of move them. I drew bodies on the material, bodily forms, almost abstractly. I’ve always been taken by movement. I was really moved by the swaying bodies of the drug addicts I’d see on the street. At that point in the ’70s, it was heroin, which was all over the place. And the addicts on the streets where I lived looked truly like a forest of trees in the wind, because they’d be standing there, scratching, looking around, swaying slowly this way and that as they nodded, almost to the ground. There’d be maybe eight or ten people on a corner.

LGB: But they never fell, did they?

SN: They never fell!

LGB: They go so low. Where my office is now, on Eighth Avenue not far from the Port Authority, sometimes you still see an addict or two. And the other day, watching one who was really far gone, I thought, ‘I’m gonna stand here and watch this motherfucker because he’s gonna go down.’ I’ve never seen one go down. His whole body was bent. His shoulder came almost to the ground. And then he righted himself back up. It’s always just absolutely amazed me. It’s a sad sight, of course, but it’s also some kind of testament to human resilience.

SN: It’s like a dance.

RK: So the two of you never came across each other at all in those years in New York?

SN: Somehow we never did. I got pregnant and went back to California. I said, ‘I just can’t drag a stroller up and down the subway steps.’ So I went home to mama and had plenty of love there. Although I had plenty of love here, too. You do what you have to do.

LGB: There was a time when I should have met her because a bunch of artists came to New York from D.C., for a National Conference of Artists event, and David Hammons was one of them. They all went to Senga and René’s house in Harlem, but I was just too intimidated to meet David then. I knew his work and revered him, but I said to myself that I wasn’t ready to meet him. I chickened out. And I didn’t chicken out about much. Later, when I came to know David, he was the one who kept saying to me, ‘You’ve got to meet this artist named Senga. The two of you need to know each other.’ He was very generous, and he was always making connections that way.

Invitation card to the inaugural exhibition at Just Above Midtown, ‘Synthesis,’ 1974

Invitation card for the David Hammons exhibition ‘Dreadlock Series’ at Just Above Midtown, 1976

RK: And Linda, did you know you wanted to be in art from the time you were young?

LGB: Very young. I knew at the age of four or five. I announced to my parents I was going to be an artist, and they put me in art school when I was six. I come from a family that had very, very few financial resources. I don’t know how they found money to take me to Saturday art classes, but they did. When I was 12, I’ll never forget, we always had Sunday family dinner on my mother’s side. We called my grandmother Big Mom. This one Sunday at dinner, somebody said, ‘Linda, what are you gonna be?’ And I was the only girl, by the way, in a family of all boys on both sides.

SN: Which is significant. I always think that’s where she got her drive.

LGB: It was significant for me: ‘I can do anything better than you.’ Anyway, someone asked me what I was going to be, and I came right out with, ‘I’m gonna be Picasso’s first black mistress!’ I had been studying Picasso and was really digging his shit. And I knew he had mistresses. I thought, ‘Well, I’m a black girl from Columbus, Ohio. How am I ever going to get noticed, to get my foot into the art world?’ In my mind, the only way the world would ever look at my work would be because I was attached to someone like Picasso. Now, the word therapy was just not something that was ever mentioned in the larger black community that I grew up in, but I remember someone saying that maybe they should take me to see a therapist. I was out there. It was probably the first time I ever really appreciated the power of sheer words.

‘He asked me why I wanted to burn down the Met, and I told him. ‘It’s a racist institution. It’s living on public money but not representing the full public. Fuck you.’

RK: I know you worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art briefly when you were first here. That wasn’t so many years after the Met’s ‘Harlem on My Mind’ show, which drew huge criticism because it was about the art world of African-American New York, but it didn’t include any works of art, besides photographs.

LGB: I interviewed for a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship there, and I went in basically determined not to get it but to use the opportunity to speak my mind. I had on full Army fatigues, had a huge Afro, had my babies with me. And the guy who interviewed me first asked, ‘Why do you want to be a Rockefeller Fellow?’ And I already knew what I was going to say. I said, ‘'Cause I want to burn this motherfucker down.’ He looked at me and said, ‘Okay, wait right here.’ He left the room and went to get his superior, and I told him the same thing. Finally, they bring in Thomas Hoving, the director of the museum. And he asked me why I wanted to burn down the Met, and I told him. ‘It’s a racist institution. It’s living on public money but not representing the full public. Fuck you. I’m gonna burn this down. If I’m a fellow, I’ll know all the best places in the basement to set the fire.’ Of course, I got the fellowship. Hoving seemed to be utterly intrigued by me. He thought I was a nutcase. He would ask me to come and talk with him twice a week. I’d go to his office and his secretary would have to keep the kids and entertain them. And he and I would debate. When I say debate, it was largely around a fairly pervasive belief in New York’s art world that African Americans could not make art. I think that was a fundamental belief; that there was African art but no worthwhile African-American art.

SN: It’s now probably hard for some people to believe that was really the case, but it was. I think it’s why ‘Harlem on My Mind’ was conceived as a show with no art but just documentation—photographs of the rich cultural life of Harlem but no other works from that life.

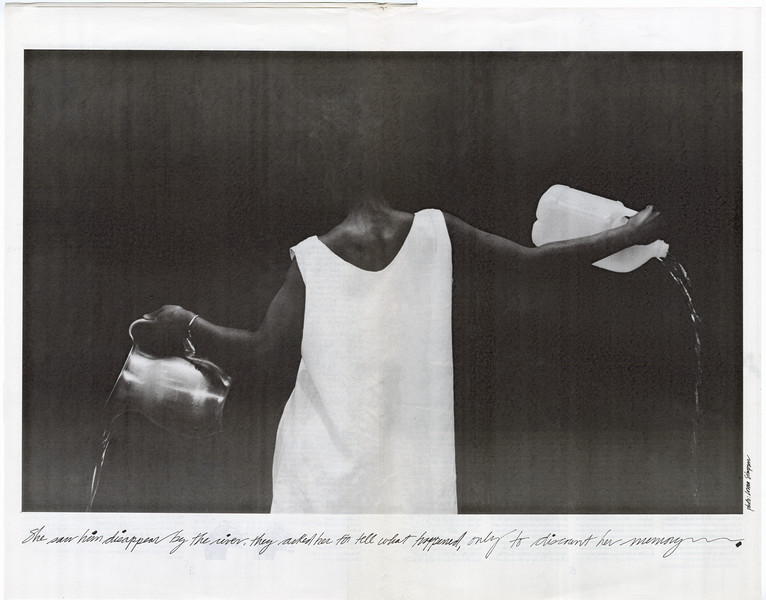

Reproduction of Lorna Simpson’s ‘Waterbearer’ (‘She saw him disappear by the river, they asked her to tell what happened, only to discount her memory.’) in B Culture magazine, a quarterly published by Just Above Midtown, 1987

LGB: Hoving would say to the curator Henry Geldzahler, because Henry was the contemporary-art guy, ‘You’ve got to talk to her.’ [Geldzahler (1935–94) was the Met’s first curator for 20th century art and one of the most revered contemporary-art figures of his generation.] Henry resented that. He’d say, ‘I’m only talking to you because Tom said I have to.’ I think Hoving was interested in anything that fell outside of his realm; he had a genuine curiosity. Or it might have been just a mode of survival: ‘If this is happening over here and I don’t understand it, it has the possibility of…’

SN: Of biting his ass.

LGB: Exactly. But Hoving protected me, because he could’ve put a kibosh on me bringing my kids to the Met. That was unheard of back then. With Henry, it was different. I don’t think he was terribly aware of what black artists were producing at that time or cared much. Though he certainly had to become more aware. When I told him I was planning to start a gallery to show black artists, he thought it was absurd. There was this thing at the time—you’re not going to believe this—that black artists mostly made paintings on black velvet. Henry and I had that discussion.

RK: Really?

LGB: Oh, yeah. Hell, yeah. More than once. It was bizarre. That whole thought was just really news to me. I mean, what?

RK: Was he just goading you?

LGB: Who ever knew with Henry? He just thought I was so naive. He was exasperated with me. But my many conversations with Henry were very good for me because they helped me put on a hard scab, so that later, when dealers themselves were hostile, I could handle it.

SN: I want Linda to tell the story about how she rented the space for Just Above Midtown gallery on West 57th Street and how the people in the building responded to her. Didn’t somebody say to you, in essence, ‘We’re not gonna let you in.’ Meaning: ‘This is our game—a male, white game.’

LGB: Yes. There were those on 57th Street who shared that sentiment. There were those who expressed it. The one I had to live with daily was the dealer Allan Frumkin. He was so angry that someone had leased me that space. Originally, I had wanted to start the gallery at 86th and Broadway, where I lived. But Geldzahler, at lunch one day, said, ‘My dear, if you’re going to have a gallery, don’t have it on 86th and Broadway. If you’re going to be serious, you have to be on 57th Street.’ Probably he was thinking, ‘You’ll never get on 57th Street.’ But a collector named Bill Judson rented me a space. To this day, I really don’t know why. We never really had conversations about it. His broker was like, What the fuck are you doing? Bill and I had no relationship other than I think maybe he connected to me in terms of passion and belief. In the face of what he knew seemed like absolute impossibility. Andi Owens, a Rockefeller Fellow who went on to found the Genesis II Museum of International Black Culture in Harlem, loaned me $1,000 for security and first and last month’s rent. Even Romare Bearden didn’t believe what I’d done. When I got the space, I ran down to Canal Street and ran up those five floors to his studio. He was like, ‘How did you get a lease?’ It was 724 square feet, fifth floor, at the back of the building, no windows. I had no insurance. I could never pay the rent. My debts to my printers are still in the archives: ‘Please pay us, Linda. Please. Please.’ There were some dealers who were very nice: the Janises, Sidney and his son Carroll; Betty Parsons was always very sweet; Terry Dintenfass, who showed Jacob Lawrence, was always supportive. But a lot of hostility otherwise. Oftentimes people would say, ‘You’re not showing 57th Street work.’

RK: Which meant what?

LGB: It wasn’t just about us being black. It was the idea of it being so out there, so experimental, very little painting. It was the thought that if you’re going to show David Hammons or you’re going to show Senga Nengudi, that’s SoHo shit; that’s not 57th Street shit. ‘What are you doing showing this on 57th Street?’ That was what that meant.

SN: And the reason you were there was to say, ‘This kind of work is worth being on 57th Street?’ Right?

LGB: Oh hell yeah. I’m glad you clarified that. It wasn’t marginal or just experimental art; it was solid art, and it belonged in the heart of the establishment and deserved to be acknowledged. It was made complicated also by the fact that, at that time, you had this ideological, philosophical, stylistic war that was going on within the black community, which has been written about a lot, but which I think some people still forget: the battle between people who worked figuratively and were very political in how they portrayed blacks in paintings or sculpture, and the group that was working in the abstract continuum of Western art, or trying to break boundaries in that continuum. And the lines of demarcation were really clear. I don’t know if Senga experienced it as much in L.A. because artists there tended to be more experimental. But in New York, you were this or that. And the whole discourse was trying to determine what a black artist was. You’re not a black artist just because you’re of African descent; you’re black as an artist because of what you’re creating. And eventually I think JAM became a place where those rigid lines of demarcation started to bleed.

SN: There was a show—show might not even be the right word—that the gallery did in 1978, called ‘The Process as Art: In Situ,’ where Linda just let a lot of us come in and make work or do performance while people watched. We basically lived at the gallery for days. It was really exciting, because you were given carte blanche, and there were no restrictions, none, related to materials, processes, anything. It was…I don’t know, it was like vibrating. That’s the kind of energy that the whole gallery had.

LGB: I have some video of you from that show, and it’s not clear exactly what you’re doing.

SN: I don’t even remember myself! But that was the way I worked and how I still work. People would say, ‘Well, send me some slides to show me what you’re planning,’ or now, ‘E-mail me some images.’ But I haven’t a clue until I get there and see the space. They’ll say, ‘I’m really looking forward to seeing what you’re going to do.’ And I say, ‘You know, I am, too.’ LGB: That’s how she is.

SN: I also think the impact of JAM had a lot to do with you making the decision to show a lot of West Coast artists like me.

LGB: That was very hard to deal with, too. Older artists sat me down and said, ‘You can’t do that. There are too many black artists in New York. You’re only gonna have a small gallery. All of us here need that space.’ That was the first time I ever thought about galleries as real estate. And then also the abstractionists versus the figurative artists. And the figurative people, some of them black nationalists, were like, ‘You gotta show us. You can’t show them.’ And I said, ‘I’m gonna show what I want.’ And let me declare myself: I was a black nationalist at the time and still believe in some aspects of its strategy and vision. But I wasn’t drawn to the aesthetic that emerged from nationalism.

SN: Talk about why that was.

Bryant as an undergraduate, Spelman College, 1968

Bryant at work on the 2003 documentary ‘Flag Wars,’ produced with the filmmaker Laura Poitras

LGB: The best experience of art, for me, is when that thing—whether it’s movement or an image or a text or a sound—opens windows and doors in my mind. And what I found in nationalist work was that its didacticism didn’t allow it to trigger my mind about what was possible. It shut it down because it was trying to teach. I would liken it to the over-texting of labels in museums now. I just can’t stand it. You cannot go into a gallery and experience the work without it being mediated by all these fucking labels that are designed and installed in locations that force you to read them. A lot of abstraction didn’t really work for me either, but there seemed to be more possibility in it. Artists were exploring, more than explaining, what they were trying to make in their work.

‘JAM was in some ways an art project for me. David Hammons always called me on it and was really upset about it. He would go, ‘Linda, I am not your paintbrush!’’

RK: You’ve said one of the things you wanted to do from the beginning was to educate collectors—black collectors, middle-class, upper-middle-class collectors—to form a generation of people who understood what their contemporaries were doing and have them buy that work, be patrons.

LGB: It was not about educating in a professorial way, but connecting—that would be the language I’d use now. Connecting people to our innate ability to use what we have to create what we need. People were saying, ‘They won’t let us.’ I was frustrated by us not letting ourselves. Not understanding that we, in fact, can create what we need. If the doors aren’t being opened for you, then go out and make your own doors. Artists need opportunities for their work to be experienced by others. So let’s just create that.

SN: I think that’s important to emphasize because that’s always been Linda’s mantra.

LGB: It was creating a base of collectors, supporters, patrons, and believers who valued and supported this creative work that was being done within the community itself, cultivating black people who had the financial ability to buy work. And to buy work that wasn’t figurative. JAM was in some ways an art project for me. David Hammons always called me on it and was really upset about it. He would go, ‘Linda, I am not your paintbrush! I am an artist. I am not your artwork.’ The fact of the matter is that we’re all artists. You run into an obstacle, and you have to figure out creatively and resourcefully how to get around it, under it, or above it. For me, the farm project, Project EATS, is kind of like a museum. It’s a new museum. You should be able to experience art, experience creative thinking, the way you could in ancient times with hieroglyphics, which was a form of communication. It was something you could experience just in the course of daily life. It wasn’t something you had to schedule or go somewhere special to see.

SN: You need to realize that that’s the other aspect of Linda: she has an MBA from Columbia, so she’s able to do what 99 percent of artists can’t do. At JAM you had a course where you taught artists how to try to make a career, right?

LGB: Oh yeah, it was a full, multiweek workshop on the business of being an artist. So it wasn’t just collectors and art lovers.

RK: After JAM moved downtown, you probably could have continued to run it as a nonprofit cultural center up to today if you’d wanted to. At what point did you decide the art world wasn’t where you wanted to be?

LGB: By the mid-’80s, it was clear. Overall, the whole culture of art had shifted toward the artist as a commodity, to a degree that continues to amaze me. I think what happened was that the resolve of artists broke down, and of course I don’t mean all artists. But what happened was that dealers were seeing Wall Street and saying, ‘Whoa, there’s all this new money we can tap to expand our businesses, to grow our sales.’ And they started placating those Wall Street folks. And what do I mean by that? It used to be that if somebody walked into your gallery and said, ‘I’m interested in buying some work that’s gonna be worth double three years from now,’ a dealer would say, ‘I can’t play that game, but I can show you this. And that. And that over there.’ The dealer would engage in helping people see something not as a commodity but as a work of art. But by ’83, ’84, ’85, dealers were more and more succumbing to what I would call ‘Let me help you find something that matches the color of your couch.’ Because the Wall Street crowd didn’t have time to learn. More and more what happened was that artists started to succumb to that mindset through pressure from dealers. Like, ‘Will you please make big things?’ And I’m not saying that was completely new, of course. But this was something different, because there was a belief and an ethics that started to get eroded. I saw work become increasingly more mediocre. I was finding myself going into JAM and saying, ‘Why am I coming in here when there’s a lot of stuff here I don’t think is strong work?’ There were artists who were really, really angry that I closed. But I couldn’t go on like that.

SN: What was it exactly about filmmaking that made you want to go that direction?

LGB: The whole way a film gets made, the process, is absolutely heaven for me. There’s nothing more satisfying than the close relationships that are necessary for it, especially documentary films—being with a group of people and being able to hone that ability to make something meaningful. From holding a camera to editing, I am on a constant high, exhausted, ready to cut my wrists because I’m so tired, but just as happy as hell. The reason I moved away from it eventually was not that, but a frustration with what it can accomplish. With Flag Wars, I really thought we had made a film where people would look at it and see themselves, understand themselves a little better. But I watched people sit in the audience and say, ‘That’s somebody else, not me.’ When it really was them. It was a reflection of them. Something about that devastated me. I realized that if you can show someone their reflection and they still refuse to see it, then it isn’t what I want be doing, even though making films is heaven for me.

Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

RK: Were you surprised when Linda told you that she wanted to start a bunch of city farms?

SN: Well, I’ve learned after all these years never to know what to expect. But, yes, that was shocking. I said, ‘But, Linda, do you know how to farm? I’ve never even seen you raise a plant. You don’t even eat healthy.’ And she said, ‘Well, maybe not, but it’s gonna be done.’ She has a driving intellect. It’s almost like a Rubik’s Cube. It starts turning, and she figures out new possibilities, new ways of doing something, and off she goes. I’m not surprised that she only eats prepared foods because she’s worked 5 a.m. to 10 p.m. most of the time I’ve known her. When do you get a chance to do the things that regular people do? So, yeah, I was surprised that she bounced from filmmaking to farms, but it was because she was working on the election at that time, and she was seeing people in neighborhoods that weren’t able to get anything other than cheap food that would harm them. There was no good grocery store. And she said, ‘Well, something has to be done about this.’ That night, she told me, she slept and had, in a sense, a vision that this thing could work.

LGB: Next year, 2019, will be our tenth year with the farms. And what I’m seeing in the communities where we farm is a shift away from a widespread disbelief that we can convert a parking lot into a half-acre farm in, say, Brownsville [Brooklyn]. We have 12 farms now throughout the city. People used to think we were crazy. And in a very short period of time—which is why farming’s wonderful—this thing they thought had no value and could not create value has value that’s very important to them, that they count on. Which is fresh food. In communities where there are tensions between one block and another, when we throw a dinner, in that moment, people feel there’s something they share. They may not feel community per se, but they’ll think, ‘If nothing else, I’m sharing this space and time with you. We’re eating food together and we’re not at each other.’ I can see that happening. Then the next thing is to move from that to helping people think, ‘If we can do this, we can do other things, make other changes politically. We can vote. We can run for office. We can find the power to push against what’s happening now in this country.’ To me, that’s one of the wonderful opportunities and challenges of what I think of as this piece of art. How to help people realize: ‘I can make the life around me what I want.’ The artist is within the human. We spend so much time talking about the artist, but we don’t talk about the human in the artist. I experience it as particularly challenging for women, especially for women who choose to have children. And then add, on top of that, women who choose to have children who are single. I was reminded of that, and moved to tears frankly, when I was watching the royal wedding on TV the other day. What really captivated me was Ms. Ragland, Meghan Markle’s mom, who’s from Ohio, like I am. And seeing her standing alone, seated alone. And when I say alone, I mean that in the most glorious, powerful way. Standing singularly there, with this daughter that she was the primary caregiver to. I was a single mother. Senga, for a while, was a single mother. And we worked.

SN: With our babies on our hips. We’ve been doing that since…

LGB: Since always. We were agricultural labor. You had that baby, and you threw that baby on your hip, and you worked. That’s how we lived.

SN: What else are you gonna do?

LGB: What else are you gonna do?

–

Learn more about Project EATS.

‘Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces’ is on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, from 9 October 2022 – 18 February 2023.