Josephsohn / Märkli: A Conjunction

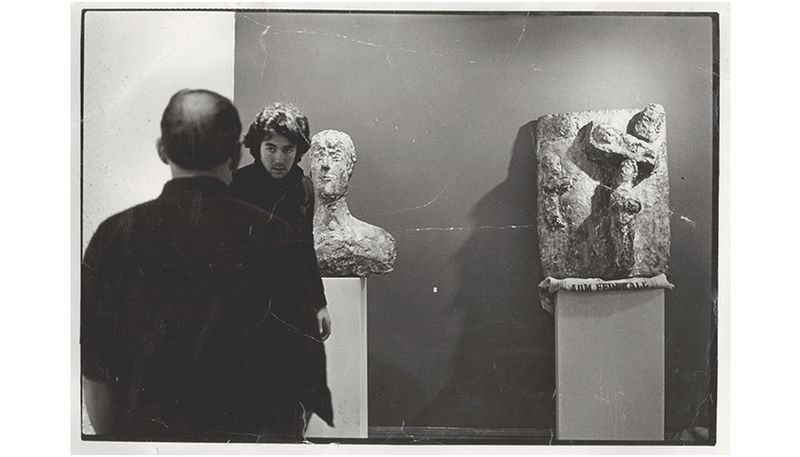

Installation view, Galerie an der Stadthausgasse, Schaffhausen, Switzerland, 1978. Photo and copyright: Simone Kappeler

Josephsohn / Märkli: A Conjunction

30 September 2017

This resource has been produced to accompany the exhibition, ‘Josephsohn / Märkli. A Conjunction’, at Hauser & Wirth Somerset and is designed for teachers and students to use alongside a visit to the exhibition. It contains an introduction by the curator, Niall Hobhouse and provides an introduction to the artist Josephsohn and the architect Peter Märkli. The key themes raised by the works in the exhibition are identified, and it makes reference to the methods and influences and some of the contexts in which their practice can be understood.

The exhibition focuses mainly on a selection of Josephsohn’s sculptures produced between the period 1950 to 2004, alongside a series of drawings by Peter Märkli that highlight the architect’s approach to drawing and his relationship with the sculptor. The works are displayed in the Threshing Barn, Workshop and Pigsty. Outside in the Piggery courtyard there is a single Josephsohn sculpture.

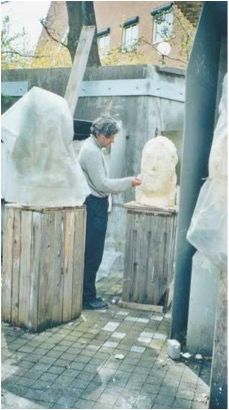

Peter Märkli and Hans Josephsohn in the Studio, 2001. Photo: Elisabeth Märkli

An Introduction to Niall Hobhouse

The idea for this exhibition came to me in a particular place at a particular moment – a narrow valley high in the Ticino, nearly twenty years ago. I remember that I asked for the key to La Congiunta at the cafe in Giornico and, touched that it was handed over without suspicion or enquiry, had walked across the river and up to the building, struggling a little with the lock. And had then spent two extraordinary hours in the falling autumn light with Hans Josephsohn’s sculptures, arranged in the simplest shed designed for them alone by Peter Märkli.

That idea has remained very straightforward: to examine the slightly elusive personal practice of two creative minds, as a way to understand an intense and enduring collaboration between them. Also, to grasp what by way of insight the two quite different disciplines of sculpture and architecture can offer to the other; and, most important, to celebrate the generosity and humanity of such exchanges. And so it has made for a wonderful experience to be asked to explore, in the galleries at Durslade, the rich material by both Josephsohn and Märkli, which speaks to these themes; and a privilege to be able to work with Ulrich Meinherz whose knowledge of the work of Josephsohn is unique. Our biggest challenge was to allow the sculptures by Josephsohn, and Märkli’s famously enigmatic drawings, to tell this story for us without just trapping visitors to the exhibition within the literal (and very powerful) spaces of the small building in Giornico.

With this in mind, we have gathered material from the two studios which includes their early efforts to find distinctive creative voices. The city of Zurich where each found himself, thirty years apart, at the start of his career could not have been more different in the social and cultural context it offered, or perhaps, more alien to both of them. This sense of being out of place initiated for each a career-long process of identifying a framework of compositional preoccupations and constraints – to be explored, questioned and adapted in the search for the certainty and assurance we then see in the work itself. In making our choices of Josephsohn’s work we have tried to illustrate this discipline by exhibiting sculptures, which demonstrate the questioning involved in the production of a range of repeated formal compositions. The point here is that every new iteration is most striking for the fascinating changes in texture and mood that it reveals.

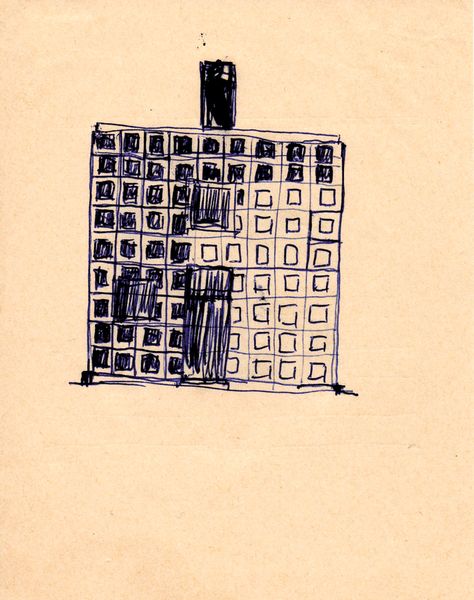

For Peter Märkli, we have tried to identify sequences of drawings that address the formal problem shared by every architect who confronts the nature of a building. As we see it, this is the composition of the simplest house facade: two storeys, an entrance and windows, and something, perhaps, to indicate a roof. In the Märkli drawings in the exhibition, this little house sometimes stands in the landscape; sometimes it is presented as hardly more than an armature for sculpture by his friend Josephsohn, sometimes as a composition of columns or of planes, or simply in obsessive studies of the critical meeting points of vertical and horizontal structure.

Towards the end of our own collaboration, Ulrich and I made the happy discovery that Märkli’s research on this subject culminates in the disciplined abstraction of the narrow entrance facade of La Congiunta itself. His work as an architect has found its simplest and strongest expression here – in unadorned concrete, without windows, a narrow door and a box skylight above, both set off-centre. Focused up till this moment on a search for human scale through the reinterpretation of classical vocabulary, and on the careful incorporation of Josephsohn’s figures and reliefs into the built fabric, the facade of La Congiunta is now without any ornament, column or capital. In the long top-lit gallery beyond, we find the sculpture presented at a gentler scale and with an altogether new intimacy.

For Märkli, the painterly flatness of the drawings – indeed, of the building facade itself – now seems to be a mask that has been made to theatrically conceal the subtle spatiality of the buildings. In Josephsohn’s relief panels we perhaps see a parallel movement. His moulded human figures, arranged in intricate spatial relationships to each other, are eased gently towards a final form that is both essential in itself, and essentially planar and rectangular. Somewhere, in fact, between the three dimensions of sculpture and the confrontational directness of painting.

Peter Märkli, 'Drawing of Facade Studies', 1980-1999, Pastel and pen on paper, 21 x 19.7 cm / 8 1/4 x 7 3/4 in.

Josephsohn, 'Untitled', 1962-64, Releif, Brass, 73.5 x 63.5 x 24 cm / 28 7/8 x 25 x 9 1/2 in

About Josephsohn

Josephsohn was born in 1920 in Königsberg, Germany, and he lived in Zurich until he died in 2012. On completing high school in 1937, he left his homeland and moved to Florence with a small scholarship to study art. However, due to his Jewish ancestry, he had to leave Italy a short time later and he fled to Switzerland. In 1938, at the age of 18, he arrived in Zurich and became a student of the Swiss sculptor Otto Müller. In 1943 Josephsohn moved into his first atelier, and by 1964 his sculptures were being shown in exhibitions across Switzerland. In 2003, at the age of 83, Josephsohn received the City of Zurich art prize. The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam dedicated a large solo exhibition to the artist in 2002. He lived and worked in Zurich until his death in 2012.

Josephsohn’s major exhibitions include solo presentations at Kunstparterre, Munich, Germany (2015); Modern Art Oxford, Oxford, England (2013); Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, England (2013); Lismore Castle Arts, Lismore, Ireland (2012); the 13th International Architecture Exhibition, ‘Common Ground’, Arsenale, Venice, Italy (2012); group exhibition ‘Visible Invisible: Against the Security of the Real’, Parasol unit foundation for contemporary art, London, England (2010); and retrospectives at the Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, Germany (2008), and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (2002). Josephsohn was also prominently featured as part of the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013.

There are two permanent installations of Josephsohn’s work open to the public: Kesselhaus Josephsohn, an exhibition and gallery space in St. Gallen, Switzerland and home of the estate of the artist; and La Congiunta, a small museum in Giornico, Switzerland, designed by architect Peter Märkli, Josephsohn’s long time friend.

Peter and Anna Märkli and Hans Josephsohn in the Studio 2001. Photo: Elisabeth Märkli

Themes

Although Josephsohn’s sculptures are essentially figurative, his work is not necessarily portraiture. The sculptures show some relationship to the actual model that posed for him in his studio but are not necessarily recognisable as portraits. Josephsohn was concerned not to produce a naturalist image but to capture the sculptural qualities of the subject: hair, or a nose, or chin, and the relationship of these forms in terms of proportion and space. Therefore his main theme is what makes humans human, and this is explored through the language of sculpture.

His style of working does not appear to fit within any particular movements at the time. The artist’s remodelling of the ancient concept of the bust, through the representation of the head and part of the torso, appear as raw and expressive forms. Their abstract qualities evoking natural geologic formations, yet, they are wholly inspired by reality. The majority of the sculptures in this exhibition are relief works, which show a series of art works that depict everyday situations, sometimes individuals in an environment or the relationship between figures in a space; they have an energetic presence that somehow captures the relationship between the male and female figure. ‘Untitled’ (2004), in the Threshing Barn, shows a half figure sculpture. For such works Josephsohn worked with live models, sculpting women with whom he had a close relationship, such as his wife, his son’s wife and other close acquaintances.

Josephsohn prioritised working from life; even in abstraction, the artist began with the model and sought to capture the presence and distinctiveness of the individual. Therefore Josephsohn’s sculptures focused on the human figure as a volume in space. His sculptures could be described as straightforward rather than expressive or imaginative in their abstraction. He worked, always from the model, on sculpture’s most constant themes: representations of the human figure, standing, sitting, reclining; working on portrait heads or half-figures, made in plaster, some then later cast in brass or bronze.

Josephsohn, 'Untitled', 2004, Half-figure, Brass, 145 x 60 x 45 cm / 57 1/8 x 23 5/8 x 17 3/4 in.

Working Methods

Josephsohn’s sculptures can be recognised for their simplicity; mostly they are limited to the simple postures of the human body. In appearance, his sculptures evoke prehistory, ancient stone slabs and Romanesque figures. Josephsohn’s favourite working material was plaster. He found it the perfect material to record directness and spontaneity, both of which were necessary for Josephsohn’s working process. Plaster allowed him to repeatedly add material or take it away. The directness of his working process can be seen in both the energy of his figures and particularly in the traces left by this process.

For example, finger imprints can be identified on the surface, referencing the artist’s hands as they work to mould the material, such as in the example opposite. Real people, such as his friends and family and almost always women, are the starting point of this work but as previously stated, his works hardly ever had portrait-like character or individual traits. Thus, also for those who knew Josephsohn’s models personally, when viewing the corresponding works there are key characteristic features such as full hair or voluminous breasts for example. See ‘Untitled’ (1974) in the Piggery.

Josephsohn, 'Untitled', 1969, Reclining figure, Brass, 67 x 214 x 53 cm / 26 3/8 x 84 1/4 x 20 7/8 in.

Whilst the surfaces of his brass sculptures are rich with detail, Josephsohn’s primary concern was the balance of mass and volume. All of the artist’s initial modelling was worked in an inexpensive construction plaster, a material that allowed him the freedom to both add and remove from his form. With his bare hands or using a spatula, Josephsohn formed and spread the material onto his plaster models. Even after the material had dried, he could cut off pieces with a knife or an axe to achieve the desired form. The surface itself demonstrates a record of the artist’s creative process.

However, despite plaster’s workability being so important to his practice, Josephsohn always envisioned his final artworks to be cast in brass, embodying a rich materiality and varied patina. His preference towards this traditional patina meant that he rarely cast in bronze. In ‘Untitled’ (1974), a heavy architectural element rests on the top and the figure itself leans towards the bust, with one leg suspended over the other, it occupies an ambiguous space. The pose reminds us of Josephsohn’s reclining figures. The whole relief speaks about the exploration of the relationship of the human body in an architectural space.

Josephsohn, 'Untitled', 1974, Brass, 115.5 x 65 x 37 cm / 45 1/2 x 25 5/8 x 14 5/8 in. Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography, Zürich

Process and Influence

Josephsohn mostly made sculptures that were complete full figures, half figures and reliefs. In the exhibition there are several of his relief pieces. They each communicate relationships between figures and space. In his lifetime he made an uncountable amount of these small reliefs. They appear as a direct record of how the artist quickly sketched, three dimensionally in clay. Followed by a casting in cement, they are then cast in metal. Whilst small and limited in detail the reliefs are informative enough to read the spatial relationships between the figurative forms and their environment.

Josephsohn’s reliefs can be seen to reflect the artist’s admiration for Romanesque art shown by the figures’ spontaneity, as if breaking out into space and toward the viewer. In his later reliefs, Josephsohn reverts back to the simplification of forms, and the incorporation of architectural forms; they become more reminiscent of a fragment of a large (ancient) sculptural frieze. Josephsohn is often compared to the artist Giacometti and clearly both artists sculpt the human form and are recognised within that tradition, but similarities can also be seen in his drawings.

As with other artists to note such as Rodin, Maillol and Lehmbruck, Josephsohn shows greater influence from painters such as Van Gogh, Picasso, Soutine and Cezanne, admiring their work for their concreteness; a clear concern for modern artists in the twentieth century. In particular Cezanne, who was concerned to find a way to represent the real world in a visual language that was specific to painting. Here, we could compare the sculptor Josephsohn to a painter in his pursuit to capture his spontaneous ideas of a subject, and not work from sketches or maquettes.

Hans Josephsohn, ‘Untitled’, 1977, Graphite on paper, 29.6 x 20.9 cm / 11 5/8 x 8 1/4 in.

It is here that we are reminded of the connection between the artist and the architect Peter Märkli who also looked towards Cezanne, ‘However the more important point of connection between Cézanne’s technique of painting and the buildings of Märkli concerns the way both seem to pay attention to the development of a harmonious surface in which the colours of both the foreground and the background have a corresponding equivalence.

Märkli’s buildings, on the other hand, are invariably interrelated with the textures and colours of the local landscape.’ [1] Josephsohn says of his work that, ‘Sometimes I’m surprised that the pieces don’t look good. That’s often to do with the light; which is really remarkable. There was an interesting experience with the architect Peter Märkli, who built the museum. I once said to him: look, the relief doesn’t really work. Then he simply took it and put it in a different light. That wouldn’t have occurred to me, because I am rather inflexible or fixed, and for me, it’s mostly the way that it is just now.’ [2] [1] Mohsen Mostafavi, Peter Märkli’s ‘Approximations’, in (a cura di) Mohsen Mostafavi, Approximations: the architecture of Peter Märkli, The MIT Press, 2002 [2] ‘What’s most important is that it works: A conversation between Hans Josephsohn and Amine Haase’, in Hans Josephsohn Udo Kittlemann & Felix Lehner (eds), Published in conjunction with the Hans Josephsohn exhibition at the MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, 8 February – 6 April 2008

Hans Josephsohn, ‘Untitled’, 1970/1980, English cement, 21.5 x 14 x 8 cm / 8 1/2 x 5 1/2 x 3 1/8 in.

Hans Josephsohn, ‘Untitled’, 1991, Brass, 133 x 76 x 59 cm / 52 3/8 x 29 7/8 x 23 1/4 in.

About Peter Märkli

Peter Märkli was born in Zurich, Switzerland in 1953. He studied at the ETH Zurich, where he was professor for architecture between 2002 – 2015. Setting up practice in 1978 his first works were houses that immediately marked him out as a serious architectural mind. La Congiunta was the architect’s breakthrough building, conceived in 1992. Since then Märkli’s projects have become larger, such as his Visitor Centre for Novartis Basel in 2006, his internationally recognised offices, New Synthes, Solothurn in 2012, his apartment buildings Im Gut, Zurich in 2012 – 2014, and the School of Gastronomy, Belvoir Park, Zurich in 2014. Besides these large scale projects Märkli still realises smaller projects such as the studio-house Weissacher Rumisberg.

Former exhibitions of his work include those held at: Atelier Alexander Brodsky, Moscow, Russia (2014), Betts Projects, London, England, (2014 & 2017), Common Ground (2012), the 13th Annual International Venice Architecture Biennale, Venice, Italy; Architektur Galerie, Berlin, Germany (2008 & 2005); National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (2008); Architekturmuseum, Basel, Switzerland (2006 & 2000); Kunsthalle, Vienna, Austria (2005); Architekturgalerie, Hamburg, Germany (2003); Königliche Kunsthalle, Copenhagen, Denmark (2002); and at the Architectural Association School of Architecture, London, England (2002).

Influences

When Peter Märkli was studying at the ETH Zurich he discovered the work of Josephsohn, whose studio he began to visit regularly. Josephsohn taught Märkli how to look at sculpture and painting, they became friends and made museum visits and trips to Italy together. Their friendship was based on a shared interest: a search for something in architecture and in sculpture that signalled the intellectual and visual concentration that they both strove for. Märkli looked to Josephsohn’s sculptures as a way of escaping the weakness of formal expression in the architecture of his contemporaries.

He saw a link between the idiomatic expression he was seeking in his own architecture and Josephsohn’s very precise sculptural language. The prolific production of drawings which he made in response to this insight were generally created independently of concrete projects. The drawings show how he developed an architectural language entirely his own, which he then subsequently interpreted in the designs and development of his built projects.

Peter Märkli in the Josephsohn Studio, 2001. Photo: Elisabeth Märkli

The work of Josephsohn also offered Märkli an appreciation of the autonomous nature of the language of sculpture and he drew on this nature of art to help develop his architectural concepts. The relentlessness of Josephsohn’s practice, which explores the same sculptural issues of proportion, volumes, and mass, can be related to the series of Märkli’s drawings seen in the Workshop Gallery.

A concern for contemporary architecture that eschewed the modernist constraints that had stifled expression, social and political contexts led Märkli to his other formative mentor, the architect Rudolf Olgiati. Olgiati was born in 1910, and working in the Swiss Alps, he created a language of both abstract form and regional lifestyle. His empathy for old and new, abstraction and concreteness, indicated the relationships that Märkli was also searching for. Such concentration can also be recognised as a uniting force of the architect and artist’s practice, as in their attraction to the work of artists like Morandi, Cézanne and the architecture of Olgiati.

Peter Märkli, ‘Drawing for the new organ of Basel cathedral’, Pastel on tracing paper, 86 x 69 cm / 33 7/8 x 27 1/8 in.

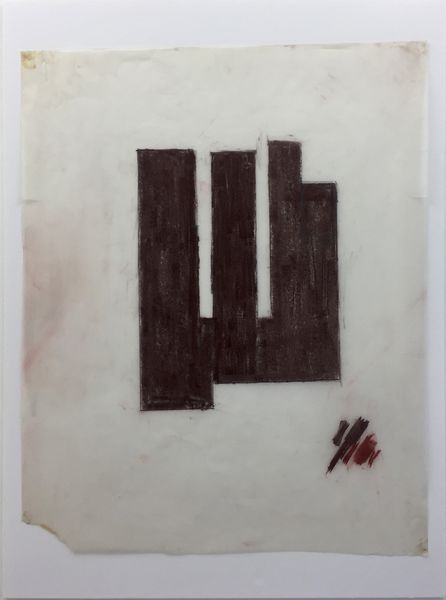

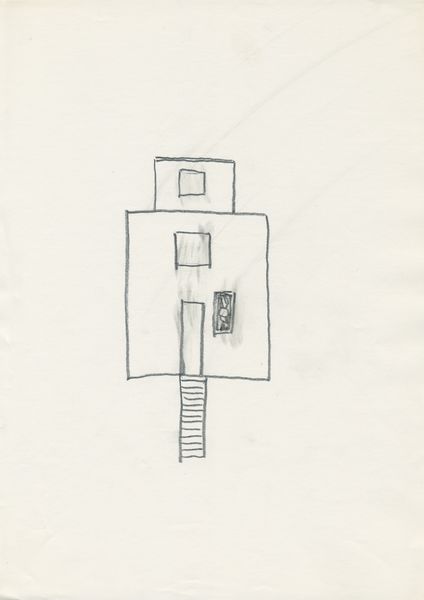

Peter Märkli, ‘Drawings of Facade Studies,’ 1980–1999, Pen and crayon on paper, 29 x 21 cm / 11 3/8 x 8 1/4 in

Working Methods

Peter Märkli’s drawings record the architect’s ideas. In this exhibition, the drawings can be seen independently or together as a series; an idea or the development of ideas. Never directly addressing a building commission, they instead record a collection of forms, a catalogue from which he can draw elements according to the buildings he is designing. He says, ‘Sometimes you have a lot of ideas but you have to wait until the point you need them. I built a building with the memory of a drawing of a facade, I think twenty years later because then the building and the situation and the landscape and all the things around needed this facade.’

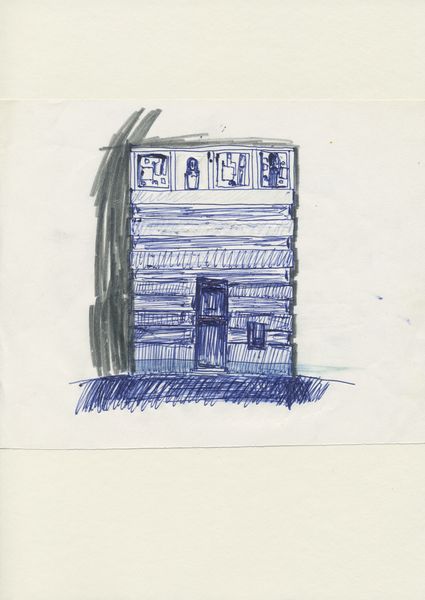

This entirely explorative drawing technique represents a huge part of Peter Märkli’s unique practice; many of his drawings are relatively small and not at all in the style of what one may expect an architect to draw. He could be considered to be defiantly rejecting the zeitgeist, and it is as if these drawings talk about his thoughts of independence. Despite their minimal nature, the drawings still demonstrate that he is considering relationships with architecture; these may be with the landscape, such as water or mountains, or with art such as sculpture, in addition with the surface or in this case the ground; which is often depicted with curved, rather than the expected straight lines.

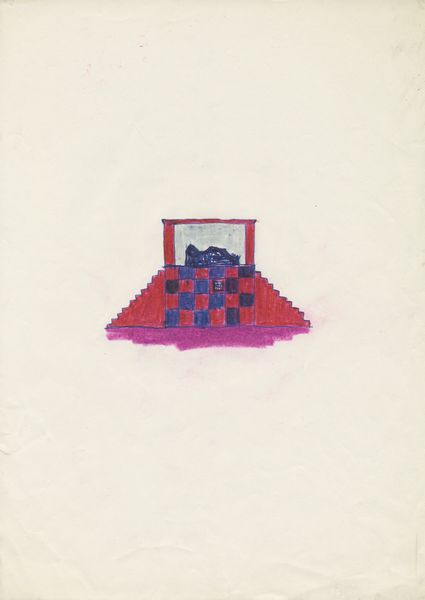

Peter Märkli, ‘Drawings of Facade Studies,’ 1980-1999, Pencil on paper, 29.5 x 21 cm / 11 5/8 x 8 1/4 in.

The drawings have a personality that is developed through the materials used. Using mostly A4 paper, and with pen or pencil, Märkli also draws with coloured pencils, often wide-nibbed, soft crayon. The use of these materials, and the drawing’s scale makes them appear both fun and cheerful through their colour, but possibly violent through their scribbling notion and repetition. Their spontaneity and rawness relate to Josephsohn’s sculptures. The use of colour in his drawing emphasises an expressive quality; they are far removed from the cool modernist style of the architecture of his contemporaries.

In a similar way to Josephsohn’s reliefs, Märkli’s drawings present some interesting dilemmas for their viewer; they could be concerned with gesture, form or architectural components and all of these things. In the relentlessness of their depiction of shapes and forms, relations between surfaces and objects, they are a constant dialogue on their language of architecture as much as Josephsohn’s language of sculpture. However, when describing his work Märkli uses the term, ‘laws of perception’, this firmly places him within the practice of architecture and not art.

Finally, this coming together, described by the exhibition’s title ‘Conjunction’ celebrates the ways in which their work is read as a reflection on the other, and their individual concerns are emphasised in this context. La Congiunta, designed specifically to present Josephsohn sculptures, continues this marriage by encapsulating the dialogue between art and architecture: the surface of the concrete of the walls, the distribution of the light, the proportion of the spaces, the position of the ceilings, and the location of the building, all make us consider the sculptures.

Peter Märkli, ‘Drawings of Facade Studies,’ 1980-1999, Pencil, coloured pencil and pen on paper, 17.2 x 21 cm / 6 3/4 x 8 1/4 in.

Peter Märkli, ‘Drawings of Facade Studies,’ 1980-1999, Pen on paper, 12.2 x 15.4 cm / 4 3/4 x 6 1/8 in.

Book Lab

The Hauser & Wirth Book Lab is a project devoted to exploring the important place that books and prints occupy in the practice of artists. Building upon Hauser & Wirth’s curatorial and publishing activities, the Lab presents thematic installations, displays, and programming that invite reflection, creative thinking, and further conversation about the world of printed matter and its connection to artists’ ideas and objectives. Many of Josephsohn’s sculptures are incorporated in Peter Märkli buildings, in his proposals, and in his studio.

The friendship and creative dialogue between the artist and architect was verbal and visual, and drew attention to issues shared by art and architecture: proportion, volume and grammar. Peter Märkli designed and built La Congiunta to house Josephsohn’s sculptures in Giornico in 1992. The building is not described as a museum, but a ‘house for reliefs and half-figures’. This Book Lab provides the space to explore La Congiunta, to see Peter Märkli’s sketches, explore printed material related to the project, to watch both the artist and architect talk about their work and finally a space for the development of dialogues, activities and events relating to the unique relationships between artists and architects.

Exterior view, Museum La Congiunta, Giornico, Switzerland, Photo: Katalin Deér

Bibliography and Supplementary Research

Permanent installations of Josephsohn’s works can be seen at La Congiunta in Tessin, Switzerland, which was built by Peter Märkli and Stefan Bellwalder and opened in 1992. The Kesselhaus Josephsohn in St. Gallen, Switzerland manages the Josephsohn estate; it houses the Josephsohn archives and presents exhibitions of his sculptures.

Josephsohn

Josephsohn website: www.kesselhaus-josephsohn.ch/kesselhaus-josephsohn www.hauserwirth.com/artists/41/josephsohn/biography ‘Hans Josephsohn an Exercise in Form & Curation’, Texts by Gerhard Mack, Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Iwan Wirth, Joe Fyfe, Caomhín Mac Giolla Léith, Thomas Houseago, Matthew Day Jackson and Rashid Johnson, Kilimanjaro, 2012 ‘Kesselhaus Josephsohn’, Udo Kittlemann (ed), MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, 2008

Peter Märkli

Peter Märkli website: www.studiomaerkli.com ‘Peter Märkli Drawings’, Claudia Mion & Fabio Don (eds), Quart Verlag, 2015 ‘Everything one invents is true: The architecture of Peter Märkli’, Pamela Johnston (ed), Quart, 2017 Peter Märkli an article by Beatrice Galilée on ICON Magazine At Betts Project: www.bettsproject.com/pm-show-images “A World without Windows” by Martin Steinmann and Beat Wismer (in Passages 30) La Congiunta, Museum in Giornico, 1992 : Architekt : Peter Märkli, Zürich. Autor: P.M.. Objekttyp

Glossary Abstract

Abstraction describes something taken from a recognisable form but not presented in a realistic way. A focus on line, shape, colour or form.

Atelier

Atelier is a French word; it is used to describe the artist’s studio.

Cézanne

Paul Cézanne was a French Post- Impressionist painter whose work is recognised for developing from the 19th- century the modern attitudes and ideas of art in the 20th century.

Classical

The period comprising the Ancient Greeks and Romans from the 6th Century BC to the fall of the Roman Empire.

Concreteness

In art, concreteness is used to define something definite as opposed to vague, and as something e.g. art that acts solely in terms of itself.

Foundry

A foundry is where metal castings are produced. Sitterwerk, where Josephsohn’s work is cast has existed since 1986 and now many national and international artists go to Sittertal to work on their ideas. See www.sitterwerk.ch/sitterwerk.html

Lehmbruck

Wilhelm Lehmbruck was a German sculptor, he mainly concentrated on the human figure.

Maillol

Aristide Maillol was a French printmaker and figurative sculptor. The architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe often included Lehmbruck’s sculptures and those of Aristide Maillol in his buildings.

Maquette

A maquette is a sculptor’s small preliminary model or sketch.

Modernism

The term Modernism is applied to many forms of art, architecture and design across the 20th century, mainly they all shared a desire to reject historical orthodoxies and reflect new technology.

Monolith

A monolith is the term used to describe a large upright block of stone or an imposing structure.

Müller

Otto Müller was a sculptor based in Zurich who tutored Hans Josephsohn.

Patina

Patina describes the colouration on the surface of bronze or similar metals. It is produced by the oxidation process.

Patination

Patination is the process and the resulting colour achieved by the oxidation process, this can be natural or manufactured through a chemical process.

Plasticity

The quality of a three dimensional material that can be easily shaped or moulded, such as clay.

Rodin

August Rodin, a French sculpture who broke new ground and paved the way for many 20th century artists.

Romanesque

Romanesque architecture describes the medieval period in Europe, recognised by its semi-circular arches.

Soutine

Chaim Soutine was a Russian artist who was a major figure in the Expressionism movement whilst he was living in Paris.

Zeitgeist

Zeitgeist is a German word used to mean the spirit of the age.

Resources

1 / 10