Don McCullin: Tate Etc. Interview

Don McCullin, Shell-shocked US Marine, 1968 © Don McCullin

Don McCullin: Tate Etc. Interview

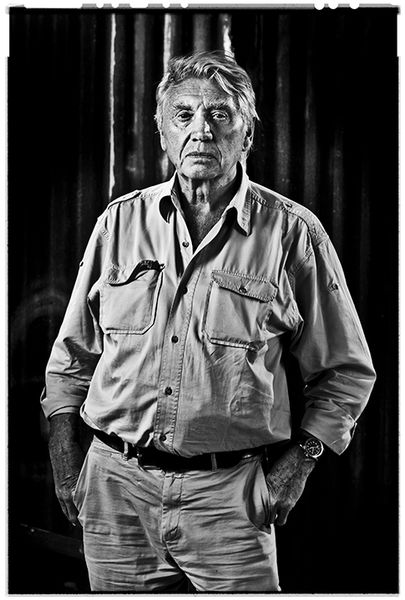

Don McCullin (b. 1935) is an internationally acclaimed photographer with over 60 years of experience documenting the world’s devastating wars and its harrowing humanitarian disasters, as well as photographing the lives of people from the industrial north of England and the homeless of east London. Undimmed by age, McCullin remains an energetic and compassionate chronicler of our world. Ahead of McCullin's retrospective exhibition at Tate Britain, Simon Grant, editor of Tate Etc., visited him at his home in the Somerset countryside to hear the story of his extraordinary life.

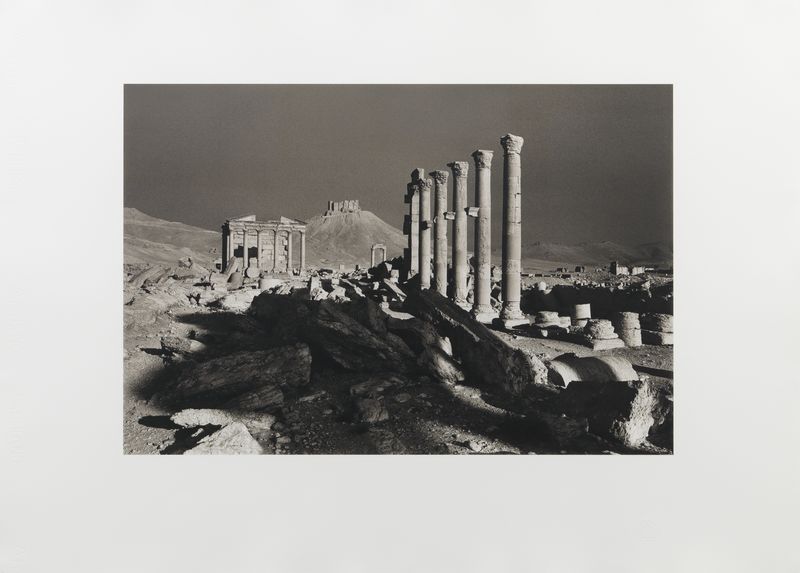

Simon Grant: In the last few years you have travelled into war-torn Syria several times, most recently to photograph the heavily bombed old city of Homs and the devastated ancient site of Palmyra. What is this urge to keep going to the trouble spots of the world?

Don McCullin: Just because I’m 83 doesn’t mean to say I have to sit here waiting to die. I’m still open to discovery. I was recently in Yemen where I spent a day with a general and his troops, photographing a lot of people whose limbs had been blown off by landmines. That evening I flew back in a Black Hawk helicopter escorted by an Apache gunship. I thought, how bloody weird – normally people like me are in a nursing home, but here I am travelling back from a war zone, in a helicopter flying 100 feet off the desert ground. Do you know why I go to these places? I think I belong there. It’s a bit of an illness that I can’t relinquish. I would really like to sit in a corner and read newspapers, but if I do, I’ll go down the drain. It’s the photographs that keep me going, physically and mentally. I just want to leave excellence behind; this is what controls me, and I like that, because it has brought me to this stage.

Don McCullin. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: © Rémy Cortin

Nikon body with bullet hole. Photo: Ken Adlard

SG: Do you think that your childhood played a part in this?

DM: I started thinking like this in my childhood. I was ashamed of where I came from. We lived in two rooms in a basement flat in Finsbury Park that was damp and miserable, with no heating and an outside lavatory. I was always wearing second-hand clothes. I remember at the weekends a lorry would back up and tip a pile of clothes onto the pavement, like a plate of spaghetti. My mother used to dive in and pull out stuff, take it home and beat the shit out of it in the washtub, and I would wear it for school on the Monday.

‘We don’t live in a black and white world, but once you see a black and white photograph, it haunts you.’—Don McCullin

SG: The way you have printed the black and white photographs that you have taken throughout your career means they are almost all very dark in tone. Do you think there would have been this darkness to them even if you had not photographed numerous wars and humanitarian disasters?

DM: I think there is a darkness in me that comes from my background. When I was five my sister Marie and I were faced with evacuation to Somerset. Marie and I were separated. She was taken to the wealthiest household in the village while I was sent to the council house. Where she lived they had a maid with a black and white uniform who used to serve her tea. I would go around to her house and peep through the window. Looking back, I think it may have been the beginning of something you can see in my pictures – an attempt to get as close to my subject while remaining invisible myself. When I was living back in London I grew up with gangsters, and even a couple of murderers. My father died at a time when I needed him the most. He was only 40 and I was 13. I left school at the age of 15 and worked on a steam train washing up in the dining car for 30 bob a week. So, I have carried that past like an indelible bloody tattoo. I’ve got more tattoos on me, psychologically, than David Beckham. I’m totally drowning and swimming in my own slightly insecure past, and all the shit that comes hasn’t changed me at all, but I think it was the very best possible way to begin my life, to prepare me for looking at other people’s tragic lives in the wars. I certainly understood poverty and violence.

Don McCullin, The Guvnors in the Sunday Suits, Finsbury Park, London, 1958 © Don McCullin

SG: When was the moment you realised that photography was your future?

DM: In 1959 the Observer newspaper published a story about a gang and its murder of a policeman in north London. Alongside it was my photograph of the gang, who lived in the area where I grew up. Seeing my name under the photograph (and being paid the princely sum of £50) gave me an enormous feeling of achievement. Where we came from you read only the Sunday Graphic or the News of the World. The most important thing to me was to see my father’s name on the page. All my working life I’ve driven myself to make his name have some meaning, which I think I’ve just about achieved.

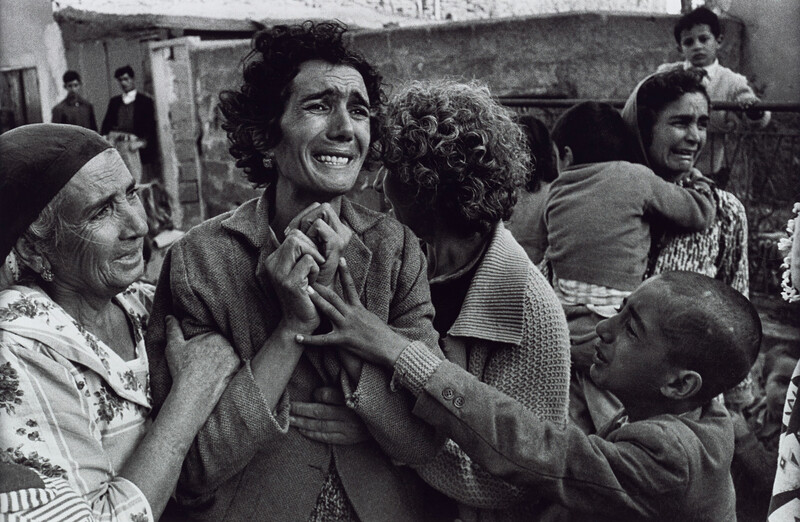

SG: In 1964, aged 28, you went to Cyprus to report on the armed conflict between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. Was that a terrifying experience?

DM: No. To be honest I found it exciting. I was running around with the bullets flying all over the place in the old Turkish quarter of Limassol, where we were coming under fire from the Greek side. It seems appalling to say it when there was a war going on and people were being killed, but I found it all rather exhilarating. I’d only ever encountered a situation like that in Hollywood films.

SG: What was it that made you want to keep returning to these conflict zones?

DM: I realised that people were trusting me, thinking that I was capable of bringing back important images. It was a great challenge and privilege. For the first time in my life I felt that the focus was on my ability. Of course, morally, one can’t use the word excitement to describe wars, but at that stage I hadn’t been injured (not until I was in Cambodia). Eventually, though, I had to learn the difference between excitement and tragedy. The moment that undoubtedly changed everything was walking into a schoolhouse one day in 1969 in Biafra during the war and finding 800 dying children. That was a monumental day of sobering up in my life, and it haunts me to this day, because some of those children were dropping dead in front of me. It reminded me of the images I had seen of Belsen some years earlier. These human beings were standing in front of me, thinking I was the great bringer of aid, and what did I show up with? Two Nikon cameras round my neck. It was a gut-wrenching, guilt-ridden experience to put that camera to my eye. By that time, I had a family of my own.

Don McCullin, Cyprus, 1964. ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland © Don McCullin

SG: What was your most terrifying experience?

DM: I was imprisoned for several days by Idi Amin’s men at the notorious Makindye military prison in Uganda in 1972. It was incredibly terrifying because we had heard that they were killing people with sledgehammers. I was there with four other press people, as well as a Tanzanian border guard. They came in one night and almost beat the guard to death in front of us. I thought, well, if they’re going to let us witness this, they’re not going to let us go. There was the constant sense that something awful was about to happen. Unlike the battlefield, there is nowhere to run inside a prison.

SG: From 1966 to 1984 you worked for the Sunday Times magazine. You covered the Biafran war, the Troubles in Northern Ireland, the humanitarian disaster in Bangladesh, the Lebanese civil war and many other conflict zones, but you are perhaps best known for your photographs of Vietnam and Cambodia. Looking back at the extraordinary photographs that were published in the Sunday Times, it seems like a special period in photojournalism.

DM: It was the most important part of my life, really. During that period, the Sunday Times attracted all the best possible people under editor Harold Evans, who let them do their professional thing, and they rewarded the paper time and time again with their brilliant investigative journalism. On the magazine we upped the ante too. At that time, in the 1960s, photojournalism in England was very much in its infancy and most people had been weaned on Picture Post or Life magazine, but the Sunday Times magazine gave people like me this extraordinary opportunity.

Display of original magazines and personal items in ‘Don McCullin Book Lab’, Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, 2018 © Don McCullin. Photo: Mario de Lopez

SG: What did you want the readers to think and feel about your photographs?

DM: I thought: ‘I’m going to shove it to them and let them see this, make life uncomfortable on a Sunday morning.’ I had to be careful that I wasn’t going overboard with my emotions, which sometimes I did a bit. If I didn’t, it meant I wouldn’t have seen the clarity of the tragedy.

SG: However, it seems incredibly important that photojournalism could play a role in telling stories that had to be told.

DM: Yes, you’re quite right but… you would never have thought in a million years that you could witness 14 year old crazed drug addicts chopping the limbs off babies at checkpoints – that anything could go beyond the intensity of that madness. Then along came ISIS – putting men in cars then firing shoulder-guided missiles at them, and burning pilots alive in cages. Looking back on it, I’ve totally failed, haven’t I? Because as soon as one war is over, another one comes along.

SG: But you have created an awareness...

DM: It’s a good word, awareness. But where does it end up taking us? Look at the Rohingya story in Burma.

SG: Do you think people found your work too powerful to deal with? Now you don’t see the visceral horrors of war, famine and conflict in newspapers and magazines.

DM: The Sunday Times really stuck its neck out. It was a very radical thing to have done. Nobody should sanitise the truth: you should always be given the opportunity in a democratic society to see the truth and not have it dusted down before it’s shown. Now we are hearing and seeing less and less about what’s going on in the world.

SG: When you look back at the photographs, have you become desensitised at all?

DM: Not at all. If I did, I wouldn’t be able to produce these pictures. I could only produce these pictures by the pain I suffer, and the shame I suffer. I live in this house with 60,000 negatives in these filing cabinets and several thousand prints, and they are all based on quite nasty subject matter. I’ve felt that when I’m asleep upstairs at night these ghosts get out of the filing cabinets and they contaminate the house.

Don McCullin, Wounded Soldier against wall, Vietnam, 1968 © Don McCullin

SG: Do you revisit the experiences of your past?

DM: Mentally, yes, I do. Particularly the Battle of Hue. I go into this battle nightly. I can’t build any walls or doors strong enough to keep these things from my bedroom. When I’m lying in bed at night trying to sleep, I have to shut down. I’ve found a way of saying don’t think, don’t think, leave this kind of blank patch for sleep. And it works. I never have a night in my life without intense dreams, but not as much as they used to be. In the old days I would have dreams of people pointing a gun in my face and pulling the trigger, but not any more.

SG: As well as documenting these conflicts, in between foreign assignments you also spent several years working closer to home, exploring the grit and grime of post-war Britain, from the homeless communities in east London to the industrial towns of northern England.

DM: Yes. I went into international conflict and then I came back to social conflict. I used to get letters from people saying they wanted to be a war photographer, and it annoyed me intensely. If you want to be a war photographer, go around the cities of England where you will find all the social wars. In Bradford, in 1975, I photographed a woman called Miss Wade. Taking the picture was like looking at my past. It was the kind of place I had lived in. And the first thing you notice about these places is the smell. Where I lived in north London there was nothing but places like that. Bradford was an extraordinary place. People would say: ‘Are you from the press? Come inside this house’, in order to show me their living conditions.

Don McCullin, Local Boys in Bradford, 1972 © Don McCullin

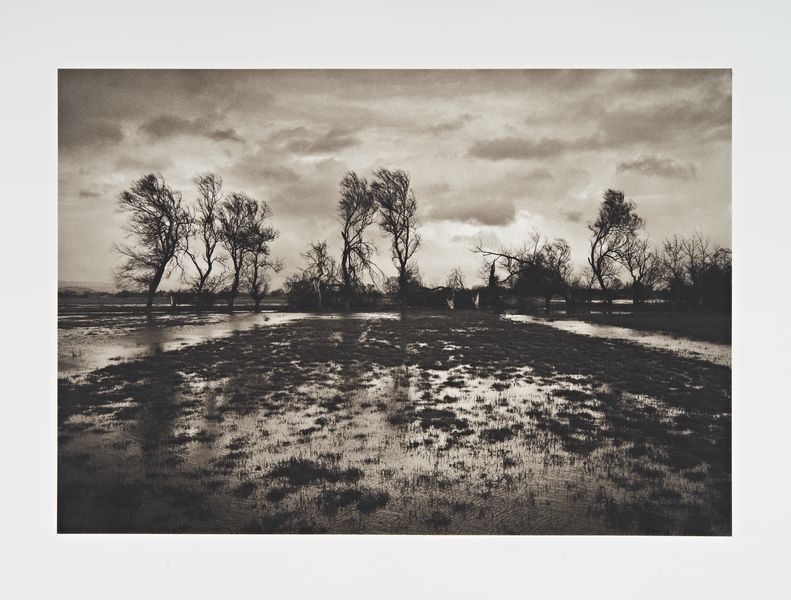

Don McCullin, Somerset Levels, Glastonbury, 1990 © Don McCullin

SG: In addition to this social documentation, you have been taking photographs – only in winter – of the Somerset landscapes near your house for over 20 years. Why did you start photographing the landscape?

DM: Landscapes freed me from the emotional garbage that I was carrying. I could go out into the landscape and have no reason to have any moral thoughts. But in the end, while taking these photographs, I suddenly realised that, there, everything I was looking at had a political dimension too: dairy farms closing, more land being taken up for housing... So even my landscapes are political, and not just in Britain. My landscapes have also recently been incorporating the destruction of Palmyra and similar places, which are totally politicised.

SG: Several decades ago you bought a pile of second-hand photography books from the series called Photograms of the Year: The Annual Review of the World’s Pictorial Photographic Work. You studied them a lot – you even called these books your ‘university’. Who are the photographers that you admire or have influenced you?

DM: The first photographer whose work I fell in love with was Alfred Stieglitz. He had a discipline that I admired, which was not to let anything out of the darkroom that wasn’t the best. Also, I have always loved Josef Sudek’s work. I put him on the top of my list, even though I weaned myself on Stieglitz and Edward Steichen. Sudek lost his right arm while in the Austro-Hungarian Army during the First World War and had to load his film with one hand, sometimes using his teeth. War must have made him feel he had to turn his disadvantage into the poetically beautiful: photographs of condensation on the windows of his Prague flat, flowers, the tree in his garden in winter. He was a bit like me in one way, because he started experimenting with darkness, and in the end his pictures looked as if he had just got a felt-tip pen and made a square of black. He was entrenched in that moment of darkness, like a wave of his past coming back to him.

SG: Whose work do you keep going to look at?

DM: Alvin Langdon Coburn, who did a lot of work in Camden Town; Peter Henry Emerson’s photographs of reed cutters on the Norfolk Broads are stunning; and Henry Peach Robinson’s bizarre set-ups, which are almost Pre Raphaelite. A hero of mine is the 19th-century photographer Francis Frith who is best known for his photographs of the Middle East – and another of my great heroes is an artist called David Roberts. I have some of his prints. He painted the Middle East and created incredible skies in his paintings. I am also interested in other people who went to the Middle East in that period – not just the photographers and artists, but also the travellers, such as Lady Hester Stanhope and Gertrude Bell.

Don McCullin, Palmyra, Syria, 2005 © Don McCullin

SG: You have clearly defined yourself as a photographer rather than an artist. How do you feel about showing How do you feel about showing at Tate Britain?

DM: Yes, good question, because my pictures were never meant to be at Tate or any other museum in the world. As newspapers won’t publish these images, though, they must have a life beyond my archive.

SG: Why are you not showing colour photographs in the exhibition?

DM: We don’t live in a black and white world, but once you see a black and white photograph, it haunts you. I have done a few pictures of wars in colour, but they don’t work – they feel too cosy – while black and white photographs will penetrate your memory.

SG: Which are the photographs you are most happy about?

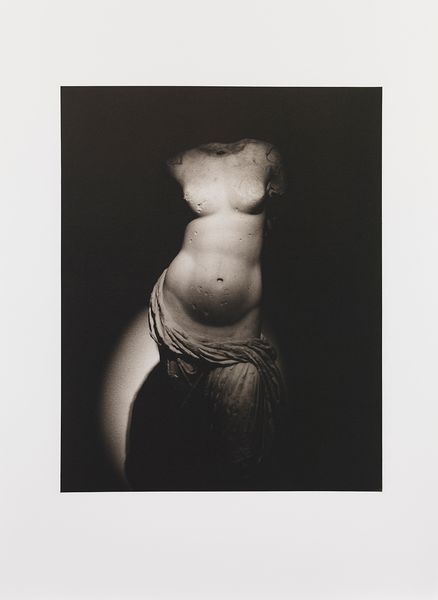

DM: I’m very proud of my photographs of the architectural ruins of the Roman Empire, like those at Palmyra. When you are standing in front of these great sites, you can hear the ringing of the pain of the people who built them, whose lives were sacrificed by the industrial side of creating these places. I think some of the best work I’ve ever done was because I was working out of my comfort zone. But my favourite picture in the whole collection was taken in the National Museum in Libya. It’s simply a piece of a Roman bust, lit by one light from above, taken at a 15th of a second with a wide-open lens. It is a picture that allows me to sit in a neutral place, having that moment of freedom, away from war, away from everything. I can’t help feeling that there is somebody up there who’s been brushing away the broken glass in my path ahead. I could have been killed in the wars. I used to run across those battlefields, zigzagging my way across the fields. I would think: ‘I’m not going to let a sniper get me’, though one day a bullet hit my camera instead. What I find extraordinary is how life can suddenly throw you in a different direction altogether. I think I’m one of those people who’s been bloody lucky really.

Don McCullin, Aphrodite, found in the Hadrianic Baths of Leptis Magna, Tripoli Castle Museum, Tripoli, Libya, 2009 © Don McCullin

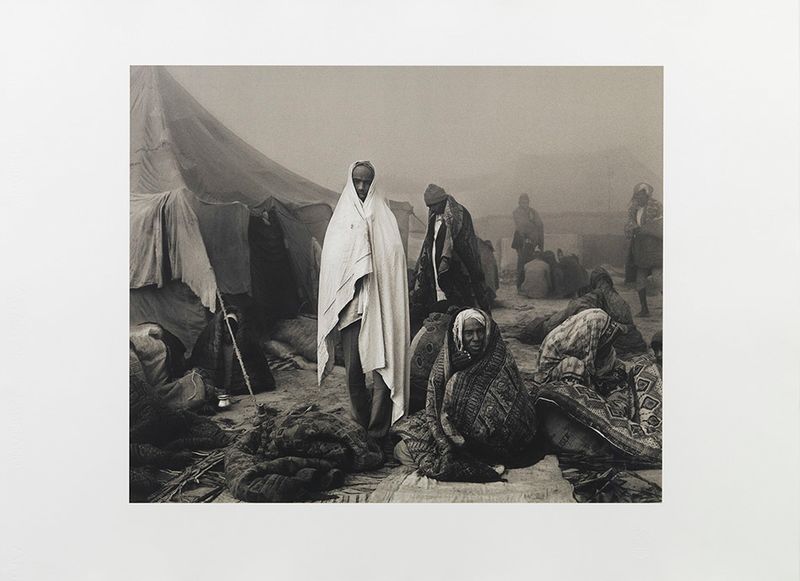

Don McCullin, Pilgrims, early morning at the Kumbh Mela, Allahbad, India, 1989 © Don McCullin

‘Don McCullin’ is on view at Tate Britain from 5 February – 6 May 2019, and is curated by Simon Baker, Director, Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, Shoair Mavlian, Director, Photoworks and Aïcha Mehrez, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain. Supported by the Don McCullin Exhibition Supporters Circle and Tate Patrons. Don McCullin lives in Somerset. Simon Grant is Editor of Tate Etc.

Related News

1 / 5