Philippe Vandenberg: The Cult Artist Who Demanded Total Freedom, Whatever The Cost reviewed by Artsy

Philippe Vandenberg, 'No title', ca. 2007 © Estate Philippe Vandenberg. Courtesy of the Estate Philippe Vandenberg. Photo: Joke Floreal

Philippe Vandenberg: The Cult Artist Who Demanded Total Freedom, Whatever The Cost reviewed by Artsy

8 March 2018

‘During my youth, I was forced into a system I didn’t believe in,’ Philippe Vandenberg told fellow artist Ronny Delrue in an interview conducted a decade ago, describing his upbringing in Belgium.

‘I was compelled to create a single order and remain in that order. But I couldn’t live like that. I wanted something different, but I couldn’t articulate what it was. To this day, I can only say what I do not want.’ Vandenberg’s unyielding spirit would make him a cult favorite among artists in his native country and beyond, but that integrity came with a cost.

In the 1980s, the painter built a fanbase (and a market) with splashy, chaotic abstract canvases – only to wilfully confound his supporters by abandoning that successful aesthetic in favor of a decades-long process of stylistic reinventions.

In 2009, Vandenberg cut short his own career by committing suicide at the age of 57. ‘In the ’80s he became famous quite fast, and it was like he was in a golden cage,’ Vandenberg’s daughter Hélène tells me. ‘So he destroyed it, this whole system he was a part of, the art system that took him in. He said, ‘I have to be free.’’

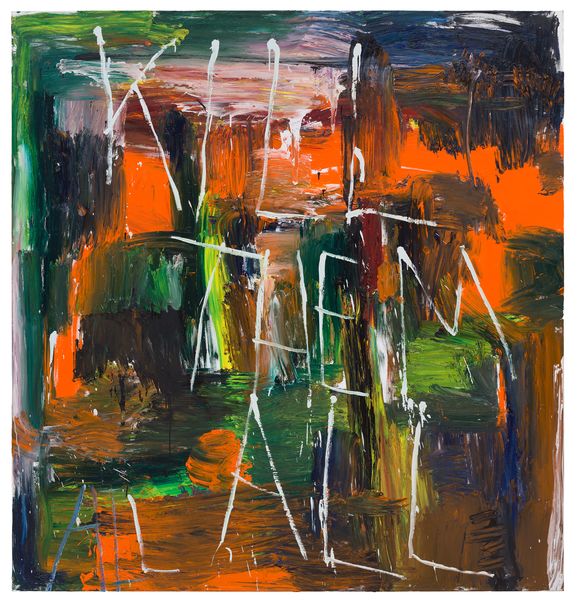

Philippe Vandenberg, 'Kill Them All I', 2005 – 08 © Estate Philippe Vandenberg. Courtesy of the Estate Philippe Vandenberg. Photo: Joke Floreal

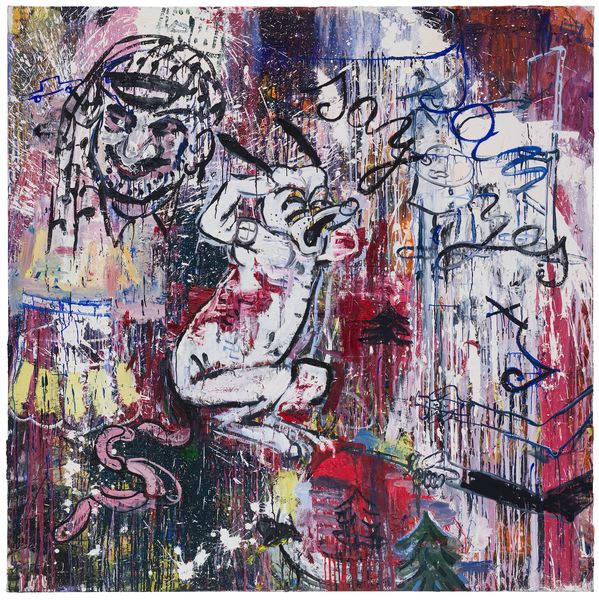

Philippe Vandenberg, 'Arafat painting', 1990 © Estate Philippe Vandenberg. Courtesy of the Estate Philippe Vandenberg. Photo: Joke Floreal

He would begin by layering cartoonish figurative elements atop his signature abstract compositions – like a grinning man pushing a wheelbarrow full of cash, or a likeness of Yasser Arafat floating above a dog that appears to be defecating sausage links. Needless to say, some formerly supportive critics and collectors were not pleased. From there, Vandenberg would gleefully follow his practice wherever it led him: to monochromes, text drawings, violently surreal figurative scenes, deceptively cheerful scenes incorporating swastikas, and soothing geometric compositions.

‘For him, a style was completely irrelevant,’ Hélène says. ‘In his career, he took a motif, he worked on it, and once he had the feeling that he’d become immobile – he destroyed it to start a new one.’ It helped, she admits, that Vandenberg had a small but committed cohort of peers and collectors in Belgium who’d stuck by his side. But that didn’t make daily life any easier for the artist. ‘He lost a lot of friends because he didn’t want to make any compromises,’ Hélène says.

Though he was able to financially support himself, ‘on the human level… he didn’t have a lot of followers anymore [by the end of his life],’ Hélène continues. ‘People didn’t understand how he changed his work again, and again. And for him, it was that he was always telling the same thing—it’s only the surface that changes.’

Philippe Vandenberg, 'No title', ca. 2008 © Estate Philippe Vandenberg. Courtesy of the Estate Philippe Vandenberg. Photo: Joke Floreal

Part of Vandenberg’s malleability can be attributed to the sheer breadth of his influences and affections. That list includes artists and writers like Philip Guston, Oscar Wilde, Rembrandt, Francisco de Goya, Mike Kelley, Louise Bourgeois, Samuel Beckett, and Raoul de Keyser (the fellow Belgian painter whose casual but affecting output perhaps seems most simpatico with Vandenberg’s collected works).

Vandenberg’s estate is now represented by Hauser & Wirth, a relationship that was catalyzed by the Belgian artist Berlinde de Bruyckere, who also works with the powerhouse gallery. An exhibition at its uptown New York space underscores the fact that – personal turmoil aside – the artist was creatively prolific until the very end.

Philippe Vandenberg, 'No title', 1996 © Estate Philippe Vandenberg. Courtesy of the Estate Philippe Vandenberg. Photo: Joke Floreal.

The show, curated by Anthony Huberman and on view through July 28, brings together paintings, sketches, and works on paper completed in the three years before Vandenberg’s suicide. Writing is a connecting thread, with words often rendered in an energetic colored-pencil scrawl. One small room in the gallery is hung with a row of text pieces, whose language relates to Vandenberg’s final studio in the Brussels neighborhood of Molenbeek, where he never felt fully at ease.

In some compositions, fragments of words stand in for the whole: like KA for KAMIKAZE, a term that Vandenberg often circled around and reused. The plurality of the later works shows how little Vandenberg cared for making an aesthetically cohesive statement. They represent the terminus of a career that began with intricate figurative paintings before breaking down into something stranger, more personal, and very difficult to package or categorize.

“Philippe could draw incredibly—when he was young, he made portraits—but he stopped. He said, ‘It’s fake, it’s a way to seduce people, it’s just one level,’” Hélène tells me. As he became older, she adds, he tried to avoid filters—of figuration, beauty, elegance, intellectualism, or conceptualism. “And the end of his life, all these filters were gone. And that makes it tough: You’re completely naked, no rules to protect you anymore, no norms or systems.” “He never made a compromise,” Hélène says of her father.

“It was all about being honest. If he needed to have a figure to tell his story, he used a figure. If one month later a circle was important to carry it, he would make a circle.” That rootlessness was what drove Vandenberg forward, but it also seems to have forced him into a tragic corner once he’d started to exhaust his own practice. “He could not lie,” Hélène recalls. “He said, ‘For me, art is a way of surviving, and in the end I have to look in the mirror every evening.’ But if you’re so radical, as a human being, the problem at the end is that you’re very lonely.”

Related News

1 / 5