Lee Lozano reviewed by Frieze

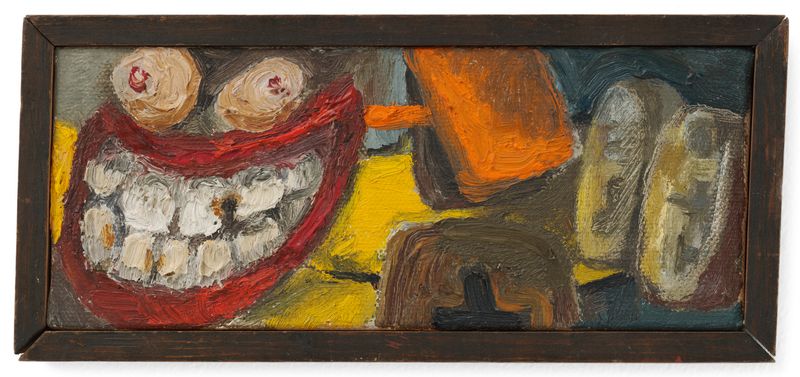

Lee Lozano, 'Untitled', c. 1962. Courtesy: The Estate of Lee Lozano. Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

Lee Lozano reviewed by Frieze

The diminutive scale of the twenty-seven paintings in ‘Lee Lozano c. 1962’ at Hauser & Wirth London may echo that of Indian miniatures, yet jewel-toned Radhas and Krishnas these are not.

Lozano’s earthen palette presents phalli, garish mouths, rotting teeth, bulbous breasts and candle-wax faces. Their depiction is cartoonish, muscular, barely contained. One jutting phallus extends beyond the canvas, nosing to the furthest tip of its rudimentary, homemade frame (all works ‘Untitled,’ c.1962).

Body parts are prone to slippage; breasts stand in for bulging eyes, a phallus for a nose. Eyes are mostly missing, blank, black, covered up or sombre smudges without definition. Elsewhere, Lozano’s thickly applied oil paint presents aeroplanes flying into or swallowed by orifices, traffic lights simultaneously flashing Stop and Go, and cardboard boxes being ruptured by their contents. A preoccupation with the permeability of bodies produces a kinetic, darkly sexy atmosphere of danger.

Lee Lozano, 'Untitled', c. 1962. Courtesy: The Estate of Lee Lozano. Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

Representing Lozano’s first major body of work, yet only now debuting as a group, these paintings may surprise. No official exhibition history exists for the series, although some works may have been included in a show called ‘Contemporary Erotica’ held at the Van Bovenkamp Gallery in New York in 1964. By the following year, Lozano had changed tack, beginning her series of huge ‘Tool Paintings’ (1963–64), which were exhibited in 1964 at Manhattan’s Green Gallery alongside work by artists including Donald Judd and Dan Flavin.

Today a cult figure, Lozano is lauded for her later, immaculately minimalist ‘Wave Series’ (1967–70) and, most of all, for her conceptual ‘life-related actions.’ (According to critic Roberta Smith in a 1999 New York Times article, the artist disliked the term ‘performance.’) These latter works included ‘Decide to Boycott Women’ – in which she ignored women, from 1971 until her death in 1999, as a way to expose gender relations – as well as ‘Dropout Piece’ (begun c.1970), which initiated Lozano’s permanent exit from the art world.

Lozano had a relationship with feminism that was, like much else in her life, complicated: she once told Rolf Ricke, her Cologne gallerist, that she believed creative energy was male energy. Phallic forms certainly visually dominate the paintings here, yet their force is often undercut by the presence of an aperture, orifice or cavity. A mid-19th-century Bowie hunting knife surging up from inside a pizza box, rupturing the flimsy material from within, is balanced by the force of a black space between the top and bottom of the box.

Later, a pillar-box-red penis wilts between two clamp-like shapes, its flaccid form defenceless against their anthropomorphic gurning.

Lee Lozano, 'Untitled', c. 1962. Courtesy The Estate of Lee Lozano. Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

Hypersensitive to shapes, Lozano wrote in a 1968 notebook: ‘It’s not just surface roundness that turns me on, it’s the feeling of density, mass, weight.’ In ‘c.1962,’ this spatial awareness can nonetheless contribute to an odd rhythmic grace. In another work, two grinning, eyeless, waxen heads enact a dance against a lapis sky. A cucumber proboscis-phallus from one head penetrates the mouth of its partner who arches pliantly towards it.

Such patterns of complex gestures, dense space and sexually charged body parts are repeated throughout the series. Included in the show is a 1963 image of Lozano shot by photographer and filmmaker Hollis Frampton, which shows the artist leaning on her desk in her New York studio. Her lips seem resigned, yet her stare is defiant. In this moment, she is a woman – an artist – in control. That these early paintings should be viewed as resolved pieces in their own right, rather than stepping-stones to later minimalist or conceptual works, is clear.

Dorothy Spears, in a 2011 New York Times article, noted that Dorothy Lichtenstein recognized Lozano’s psychosexual, political potency, commenting, ‘Lee was punk before punk.’ With this show, the timeline has changed. Lozano was ahead of herself – or we have caught up?

Related News

1 / 5