Maisons Fragiles

11 December - 6 February 2016

London

Selected images

Untitled

1975

Installation views

About the Artists

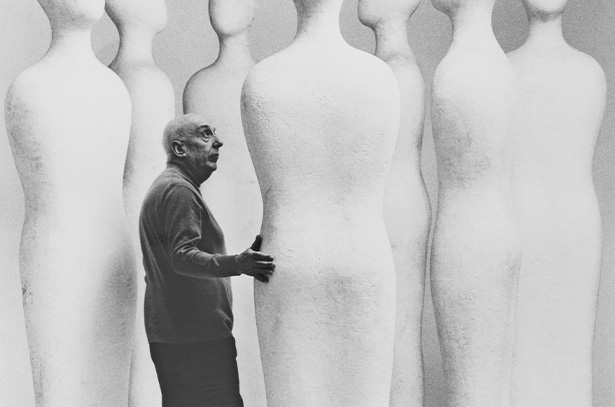

Louise Bourgeois

Born in France in 1911, and working in America from 1938 until her death in 2010, Louise Bourgeois is recognized as one of the most important and influential artists of our time. For over seven decades, Bourgeois’s creative process was fueled by an introspective reality, often rooted in cathartic re-visitations of early childhood trauma and frank examinations of female sexuality. Articulated by recurrent motifs (including body parts, houses and spiders), personal symbolism and psychological release, the conceptual and stylistic complexity of Bourgeois’s oeuvre—employing a variety of genres, media and materials—plays upon the powers of association, memory, fantasy, and fear.

Bourgeois’s work is inextricably entwined with her life and experiences: fathoming the depths of emotion and psychology across two- and three-dimensional planes of expression. ‘Art,’ as she once remarked in an interview, ‘is the experience, the re-experience of a trauma.’ Arising from distinct and highly individualized processes of conceptualization, Bourgeois's multiplicity of forms and materials enact a perpetual play: at once embedding and conjuring emotions, only to dispel and disperse their psychological grasp. Employing motifs, dramatic colors, dense skeins of thread, and vast variety of media, Bourgeois's distinctive symbolic code enmeshes the complexities of the human experience and individual introspection.

Rather than pursuing formalist concerns for their own sake, Bourgeois endeavored to find the most appropriate means of expressing her ideas and emotions, combining a wide range of materials—variously, fabric, plaster, latex, marble and bronze—with an endless repertoire of found objects. Although her oeuvre traverses the realms of painting, drawing, printmaking, and performance, Bourgeois remains best known for her work in sculpture.

Bourgeois’s early works include her distinct 'Personages' from the late 1940s and early 1950s; a series of free-standing sculptures which reference the human figure and various urban structures, including skyscrapers. The ‘Personages’ served as physical surrogates for the friends and family Bourgeois had left behind in France, while also highlighting an interest in architecture dating back to her childhood. Her installation of these sculptures as clustered ‘environments’ in 1949 and 1950 foreshadowed the immersive encounters of installation art twenty years before the genre’s rise to prominence.

Bourgeois’s work was included in the seminal exhibition ‘Eccentric Abstraction,’ curated by Lucy Lippard for New York's Fischbach Gallery in 1966. Major breakthroughs on the international scene followed with The Museum of Modern Art in New York's 1982 retrospective of her work; Bourgeois's participation in Documenta IX in 1992; and her representation of the United States at the 45th Venice Biennale in 1993.

In 2001, Bourgeois was the first artist commissioned to fill the Tate Modern’s cavernous Turbine Hall. The Tate Modern’s 2007 retrospective of her works, which subsequently traveled to the Centre Pompidou in Paris; The Guggenheim Museum in New York; The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; and The Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C., cemented her legacy as a foremost grande dame of late Modernism.

Header image: Louise Bourgeois, ARCHED FIGURE, 1993 © The Easton Foundation/VAGA, NY, Photo: Christopher Burke

Roni Horn

Roni Horn’s work consistently generates uncertainty to thwart closure. Important across her oeuvre is her longstanding interest to the protean nature of identity, meaning, and perception, as well as the notion of doubling; issues which continue to propel Horn’s practice.

Since the mid-1990s, Horn has been producing cast-glass sculptures. For these works, colored molten glass assumes the shape and qualities of a mold as it gradually anneals over several months. The sides and bottom of the resulting sculpture are left with the rough translucent impression of the mold in which it was cast. By stark contrast, the top surface is fire-polished and slightly bows like liquid under tension. The seductively glossy surface invites the viewer to gaze into the optically pristine interior of the sculpture, as if looking down on a body of water through an aqueous oculus. Exposed to the reflections from the sun or to the shadows of an overcast day, Horn’s glass sculpture relies upon natural elements like the weather to manifest her binary experimentations in color, weight and lightness, solidity and fluidity. The endless subtle shifts in the work’s appearance place it in an eternal state of mutability, as it refuses a fixed visual identity. Begetting solidity and singularity, the changing appearance of her sculptures is where one discovers meaning and connects her work to the concept of identity.

For Horn, drawing is a primary activity that underpins her wider practice. Her intricate works on paper examine recurring themes of interpretation, mirroring and textual play, which coalesce to explore the materiality of color and the sculptural potential of drawing. Horn’s preoccupation with language also permeates these works; her scattered words read as a stream of consciousness spiralling across the paper. In her ‘Hack Wit’ series, Horn reconfigures idiomatic turns of phrase and proverbs to engender nonsensical, jumbled expressions. The themes of pairing and mirroring emerge as she intertwines not only the phrases themselves but also the paper they are inscribed on, so that her process reflects the content of the drawings. Words are her images and she paints them expressionistically, which—combined with her method—causes letters to appear indeterminate, as if they are being viewed underwater.

Notions of identity and mutability are also explored within Horn’s photography, which tends to consist of multiple pieces and installed as a surround which unfolds within the gallery space. Examples include her series ‘The Selected Gifts, (1974 - 2015),’ photographed with a deceptively affectless approach that belies sentimental value. Here, Horn’s collected treasures float against pristine white backdrops in the artist’s signature serial style, telling a story of the self as mediated through both objects and others—what the artist calls ‘a vicarious self-portrait.’ This series, alongside her other photographic projects, build upon her explorations into the effects of multiplicity on perception and memory, and the implications of repetition and doubling, which remain central to her work.

Fausto Melotti

Italian sculptor, painter and poet, Fausto Melotti is considered a pioneer of Italian art and is acknowledged for his unique contribution to the development of mid-century European Modernism. Coming of age in prewar Milan, and living through the horrors of the Second World War, Melotti metabolized wartime devastation in his work by returning to Renaissance principles of harmony, order, geometry, and musical structure, which he integrated into a highly personal yet universally accessible artistic language that expresses the full range of emotional experiences in modern human existence.

Before turning to art, Melotti studied music, mathematics and engineering—disciplines that exerted clear influence upon his distinctive practice across subsequent decades. Melotti trained as a figurative artist, studying under Italy’s leading Symbolist sculptor Adolfo Wildt at the Accademia di Brera in Milan. There he befriended fellow pupil Lucio Fontana in 1928, and in the following decade shifted his focus to abstraction and a new non-objective art. Melotti developed influential friendships with the Rationalist architects of Gruppo 7 and the abstract artists who gravitated around Galleria Il Milione. With Fontana, he joined the ‘Abstraction-Création’ movement, developing firm ideas about non-figurative art. Influenced by his education in engineering and music, Melotti’s first abstract sculptures were geometrical, and echoed the young artist’s academic training in order, rhythm, proportions and form.

Melotti’s ceramics of the 1940s respond to the pain, trauma, and despair that crowded his thoughts in the aftermath of the Second World War. Aerial bombings destroyed the artist’s studio in Milan and profoundly altered his artistic vision, precipitating a literal and symbolic rupture in his idealized pursuit of abstraction. His attention shifted to the craft and production of ceramics and terracotta. Rendered in polychromatic glazes, the enigmatic figures in these works illustrate the artist’s urgent and necessary return to figuration.

By the 1960s, Melotti had returned to sculpture, using a new language built upon delicate threads and thin sheets of brass, iron, and gold to express a more resolved and distinctly humanist sensibility. Delicately wrought, almost fragile constructions became enriched by a new narrative, dream-like and symbolic. These weightless works resemble aerial drawings incorporating space, air and transparency. His later work of the 1970s and 1980s is characterized by rhythmic geometric forms with an underlying humanist narrative that curator Douglas Fogle describes as ‘quivering just on the threshold between the solidity of figuration and the immateriality of abstraction.’

Current Exhibitions

1 / 9