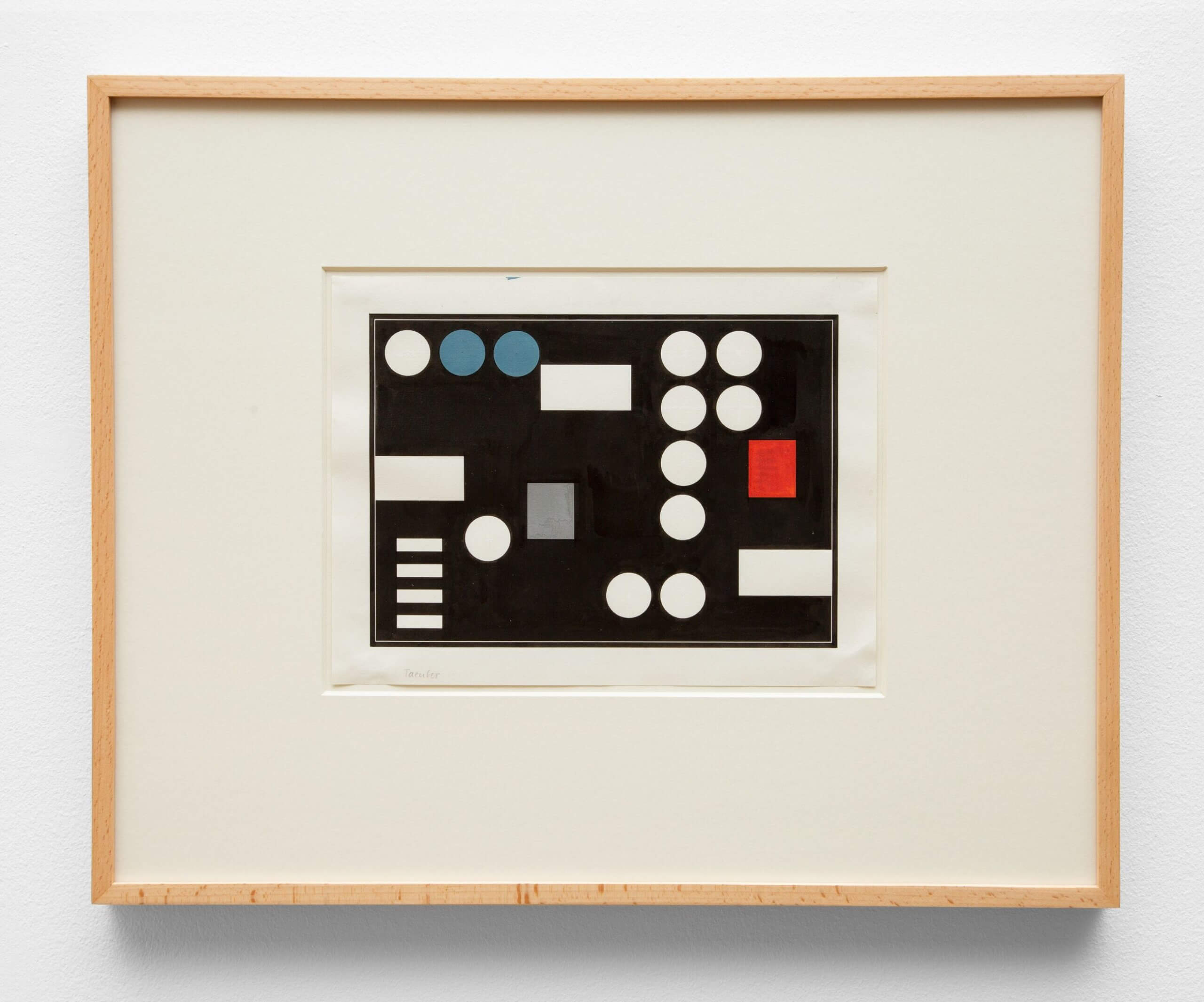

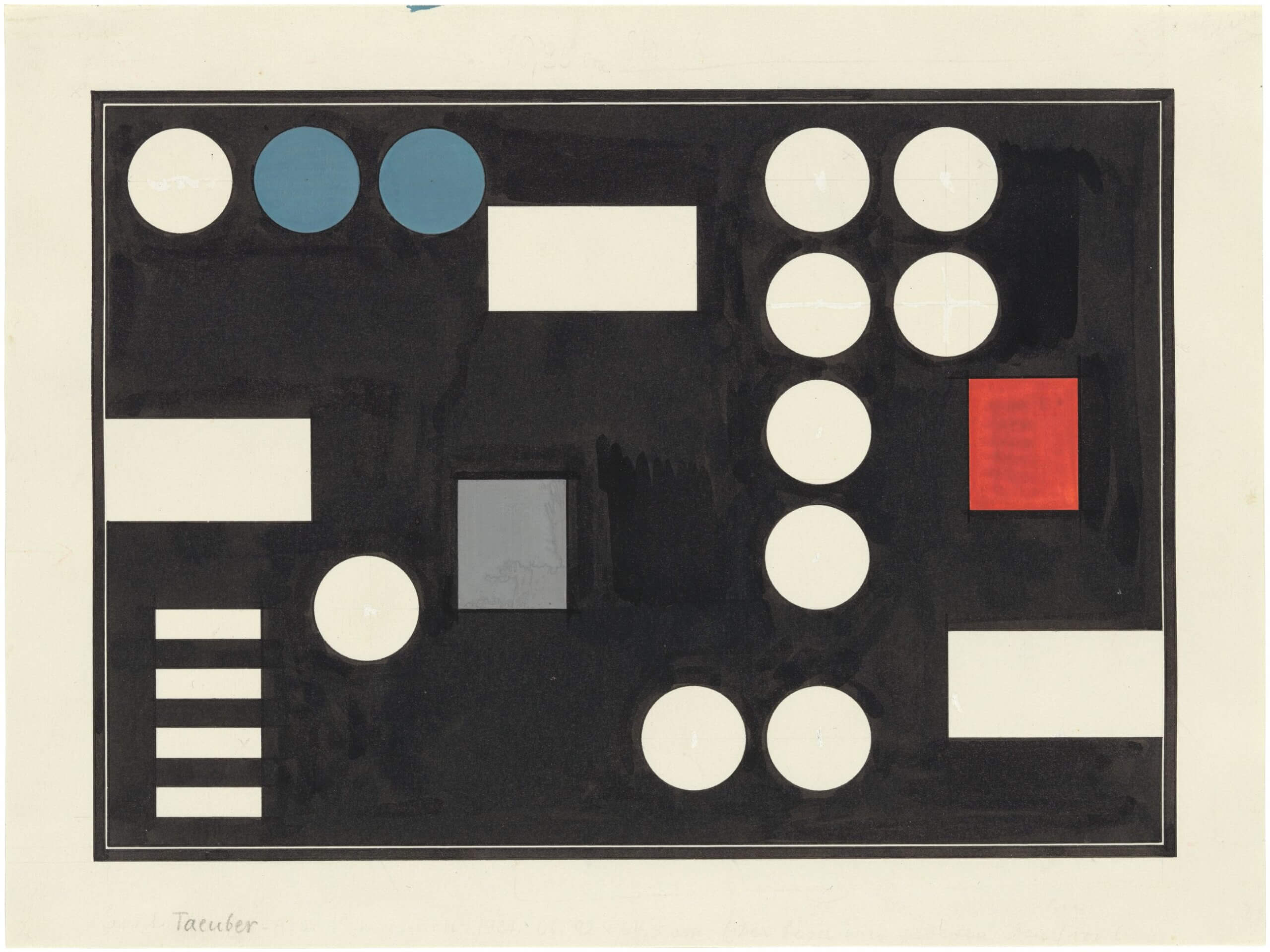

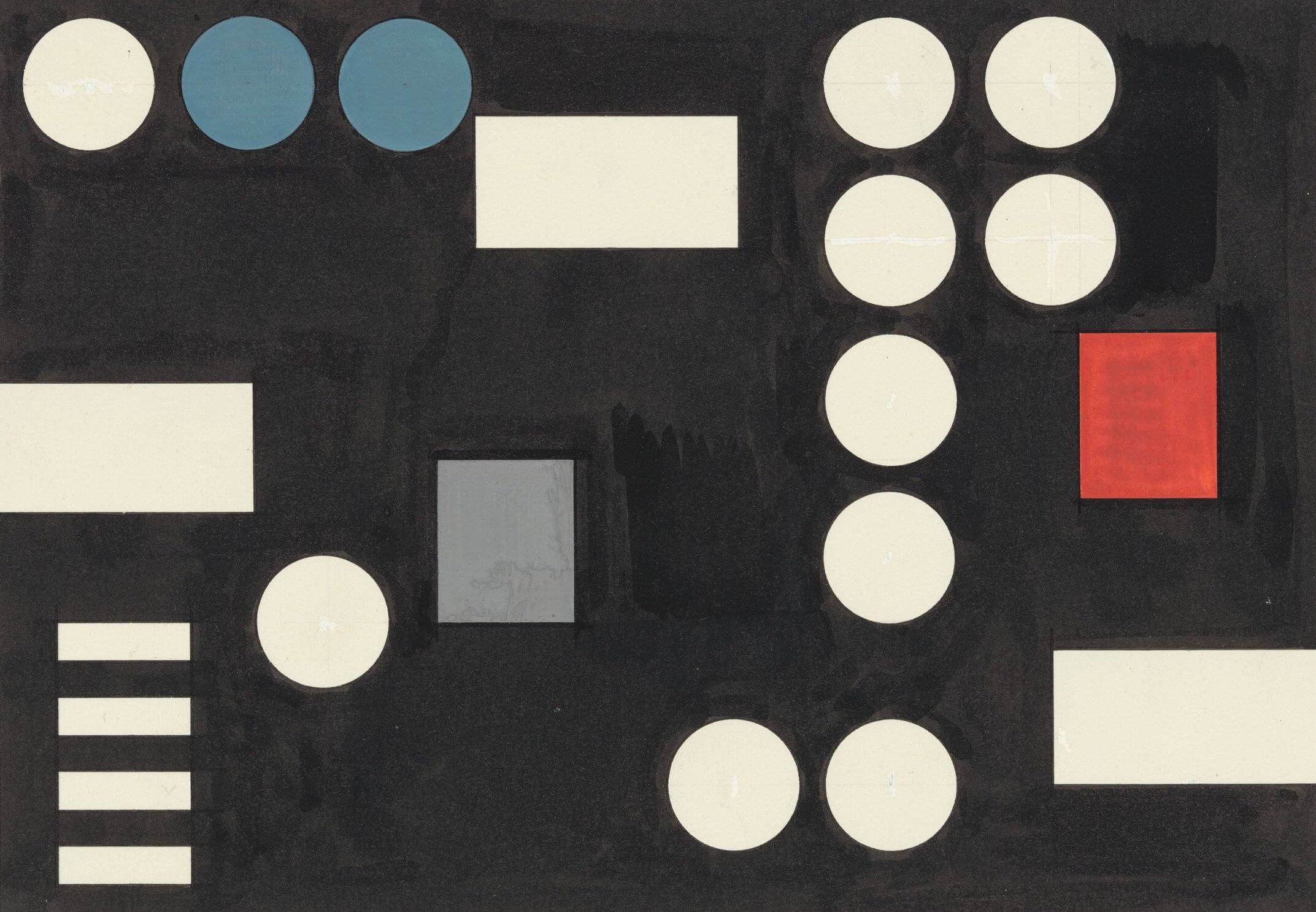

Sophie Taeuber-Arp

Composition à rectangles et cercles <br>(Composition with rectangles and circles)

Composition à rectangles et cercles

(Composition with rectangles and circles)

1931 Ink, gouache, watercolor, pencil and opaque white corrections on paper 20.5 x 27.4 cm / 8 1/8 x 10 3/4 in

‘The wish to produce beautiful things—when that wish is true and profound—falls together with [one’s] striving for perfection.’—Sophie Taeuber-Arp

Coquilles et fleurs (Shells and Flowers)

1938 Relief, painted wood 1 from a series of 3 variants Diameter: 59 cm / 23 1/4 in; depth: 8.1 cm / 3 1/4 in

‘Coquilles et fleurs’ (Shells and Flowers)

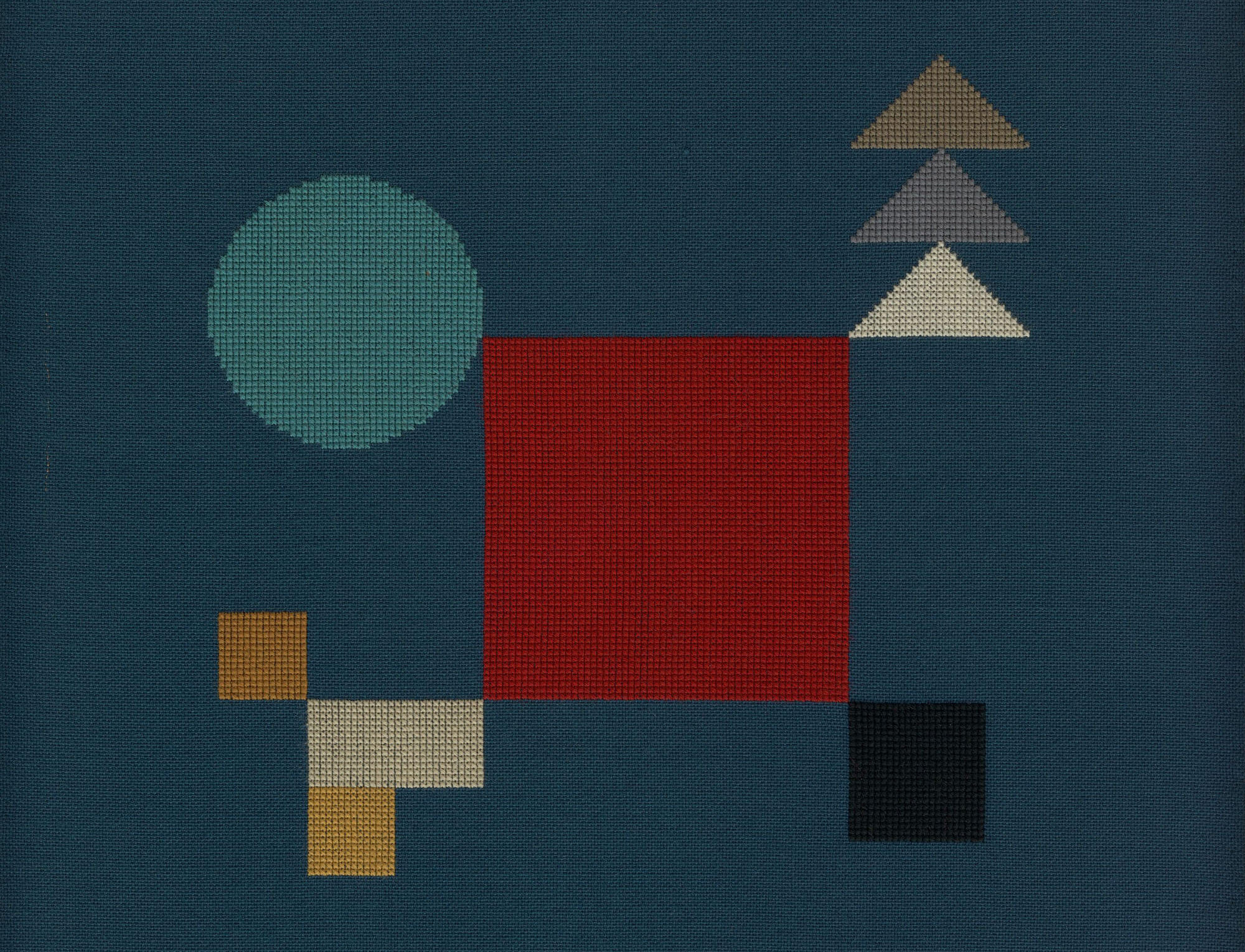

Produced in 1938, Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s ‘Coquilles et fleurs’ (Shells and Flowers) was created during an especially fruitful decade, which found her settled in the outskirts of Paris and moving within the circle of the avant-garde. In the period between her official break with Abstraction-Création, in 1934, and her founding of the Plastique/Plastic review, in 1937, Taeuber-Arp's art took a new direction in the form of painted wood reliefs. These new works synthesized the cerebral geometry of her previous ‘Ping’ paintings with Surrealist biomorphism, using the circle, square and rectangle as focal points of a composition, while adhering to triads and tetrads of colors on an otherwise black or white monochromatic ground. This shift translated into an organic vocabulary of voids and ‘shapes counterpointing shapes’, which, as the artist ultimately paired down to a monochromatic white or muted polychrome palette [2], gave way to studies in light and shadow, merging the relief into the architectural space of its surrounding wall.

While conjuring the superimposition of Kazimir Malevich’s ‘Suprematist Composition: White on White’ (1918) and the reductivist dialect of Cercle et Carré, the ingenuity of ‘Coquilles et fleurs’ lays in its evocation of natural phenomena encompassed within the framework of a circle and its interactive engagement with the act of display. [3] For Taeuber-Arp, ‘the circle was the cosmic metaphor, the form that contains all others’, engendering a seamless transition between representation and abstraction. [4] Belying its organic manifestation, ‘Coquilles et fleurs’ emerged from a series of considered actions that enabled the artist to produce three variations and which resulted in an incredibly early example of an interactive artwork that engaged both the artist and the artwork's owner. Evolving from a study on paper created in c. 1936, patterns were cut out from four panels of wood in irregularly straight-edged and curvilinear variations, which, while maintaining harmonious conformity along the circumference edge, were off-set in superimposition. ‘Constructed through a process of building forward,’ notes curator Carolyn Lanchener, ‘the effect of these reliefs is to reveal depth through surface… establishing multileveled tulip and shell-shaped forms.’ [5] Taeuber-Arp produced three versions of this form (two painted white, and one painted white with yellow accents), but she allowed the reliefs' owners to decide how each relief was to be installed. As each relief can be rotated and hung according to the individual visual preferences of their owners, three unique formal arrangements are created each time they are displayed, with new forms emerging from the interplay of carved shapes. This playful and inventive engagement with the owner is typical of Taeuber-Arp's expansive view of art, a herald of her creative genius.

Elegantly transposed into a groundbreaking series of three in muted color and form, ‘Shells and Flowers’ embodies Taeuber-Arp’s legendary sense of exuberance and its creation parallels a celebratory moment in her career, highlighted by her participation in two major exhibitions: the ‘Exposition internationale du Surréalisme’ in Paris and the ‘Exposition of Contemporary Sculpture’ in London, both held in 1938. The sophistication of ‘Coquilles et fleurs’ exemplifies Taeuber-Arp’s reliefs, which, as Wassily Kandinsky described, are likened to a whisper— often ‘more expressive, more convincing, more persuasive, than the 'loud voice' that here and there lets itself burst out’. Within Taeuber-Arp's reliefs, he declared, ‘the arsenal of the means of expression is of an inexhaustible richness…. Against the thunder of kettledrums and trumpets in a Wagner overture is set a quiet, ‘monotonous' fugue by Bach.’ [6]

[1.] Sophie Taeuber-Arp quoted in Bulletin de l’union suisse des maîtresses professionelles et ménagères/ Korrespondenzblott, Zurich/CH, vol. 14, no. 11/12, Dec. 31, 1922, p. 156. cf: Carolyn Lanchener, ‘Sophie Taeuber-Arp’, New York NY: The Museum of Modern Art, 1981, p. 9. [2.] Although the artist was interested in polychrome surfaces, it has yet to be confirmed if the citrus yellow and white variant (ed. 3/3) was painted by the artist or posthumously applied by Hans Arp. Cf. Rudolf Koella, ‘Coquilles et fleures*’, ‘Sophie Taeuber-Arp. 1889-1943’ Stephan Kunz, Aargauer Kunsthaus (eds.), Aarau/CH: Aargauer Kunsthaus, 2010, p. 56. [3.] Notably, Taeuber-Arp had dedicated the first issue of Plastique/Plastic to the work of Kazimir Malevich. Ibid., p. 15. [2.] Ibid., p. 13. [5.] Ibid., p. 17.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp

Sophie Taeuber-Arp is one of the most important artists of the twentieth-century avant-garde and is considered a pioneer of Constructivist art. Reconciling extremes with confidence—Dada and Geometric Abstraction, fine art and utilitarian objects—Taeuber-Arp’s works boldly engaged with the intellectual context of international modernism. Through her multi-faceted approach to media, she challenged traditional hierarchies between fine and applied art, and asserted art’s urgent relevance to daily life.

Modern Master

Learn about the life and work of Sophie Taeuber-Arp in this film narrated by Jennifer Higgie, editor-at-large of frieze magazine and host of Bow Down, a podcast about significant women from art history who deserve our attention.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp

Explore our online exhibition devoted to Sophie Taeuber-Arp including 30 works, dating from 1916 to 1942, presented alongside photography and material from the Arp Foundation (Stiftung Arp e.V.) archives. Her radical multidisciplinary approach was a constant thread throughout the distinct periods of her life and work, from her marionettes and iconic ‘Tête Dada’ (1920), to her architectural interiors and reliefs.