1 / 8

Alina Szapocznikow

Sculpture-lampe XIII (Sculpture-Lamp XIII)

- ca. 1970

- Colored polyester resin, light bulb and electrical cable

- 52.5 x 40 x 24.5 cm / 20 5/8 x 15 3/4 x 9 5/8 in

An extraordinary example from Alina Szapocznikow’s most famous body of work, ‘Sculpture-lampe XIII (Sculpture-Lamp XIII)’ (c. 1970) was one of the highlights of Roberto Matta’s important collection. In 1965, Matta was one of the jurors, alongside Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, and Man Ray, who awarded Szapocznikow the prestigious Copley Foundation prize for her sculpture ‘Goldfinger’ (1965). Encouraged by her win, Szapocznikow started creating her illuminated lips using polyester resin in the following months, eventually offering one to Matta. A pioneer in her field, Szapocznikow was among the first artists to work with the material, which is typically used for industrial purposes. Mining its expressive possibilities, Szapocznikow ingeniously adapted the translucency and color of her material to evoke the textural quality of skin. Struck by the idea of illuminating the casts of her and her friends’ body parts, she began creating her iconic glowing lips and busts. Radically redefining the concept of sculpture, Szapocznikow fragmented, disfigured and abstracted the human figure, producing casts and sculptures of body parts that were at once attractive and repulsive, erotic and abject.

Awkward, visceral, and playful bodies are as crucial to understanding Szapocznikow’s oeuvre as they are to her biography, which is inextricably linked to the art that she produced. Born in Poland in 1926, Szapocznikow and her family were first banned to the Pabianice and Łódź ghettos, and later interned at Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen. After the war, she trained as a sculptor and quickly gained international renown for her innovative work. In 1962, the same year that she represented Poland at the Venice Biennale, Szapocznikow cast her leg in plaster, initiating a groundbreaking series of works. ‘Leg/Noga’ (1962) constituted a major artistic breakthrough, as uncanny casts of the human body—a subversive choice for a female artist at the time—became her hallmark. Shortly thereafter Szapocznikow relocated from Poland to Paris. There she began to experiment with casting and molding body parts in more unconventional modern materials, as in the case of her ‘Goldfinger,’ her sardonic take on the absurdity of a sexualized, consumerist society through a reference to the notorious Bond villain, which gained her the admiration of Matta.

‘Through casts of the body, I try to fix the fleeting moments of life, its paradoxes and its absurdity ... I am convinced that of all the manifestations of the ephemeral, the human body is the most fragile, the only source of all joy, of all pain and of all truth.’

Alina Szapocznikow

About the artist

Born in Poland to a Jewish family in 1926, Alina Szapocznikow survived internment in concentration camps during the Holocaust as a teenager. Immediately after the war, she moved first to Prague and then to Paris, studying sculpture at the École des Beaux Arts. In 1951, suffering from tuberculosis, she was forced to return to Poland, where she expanded her practice. When the Polish government loosened controls over creative freedom following Stalin’s death in 1952, Szapocznikow moved into figurative abstraction and then a pioneering form of representation. By the 1960s, she was radically re-conceptualizing sculpture as an intimate record not only of her memory, but also of her own body.

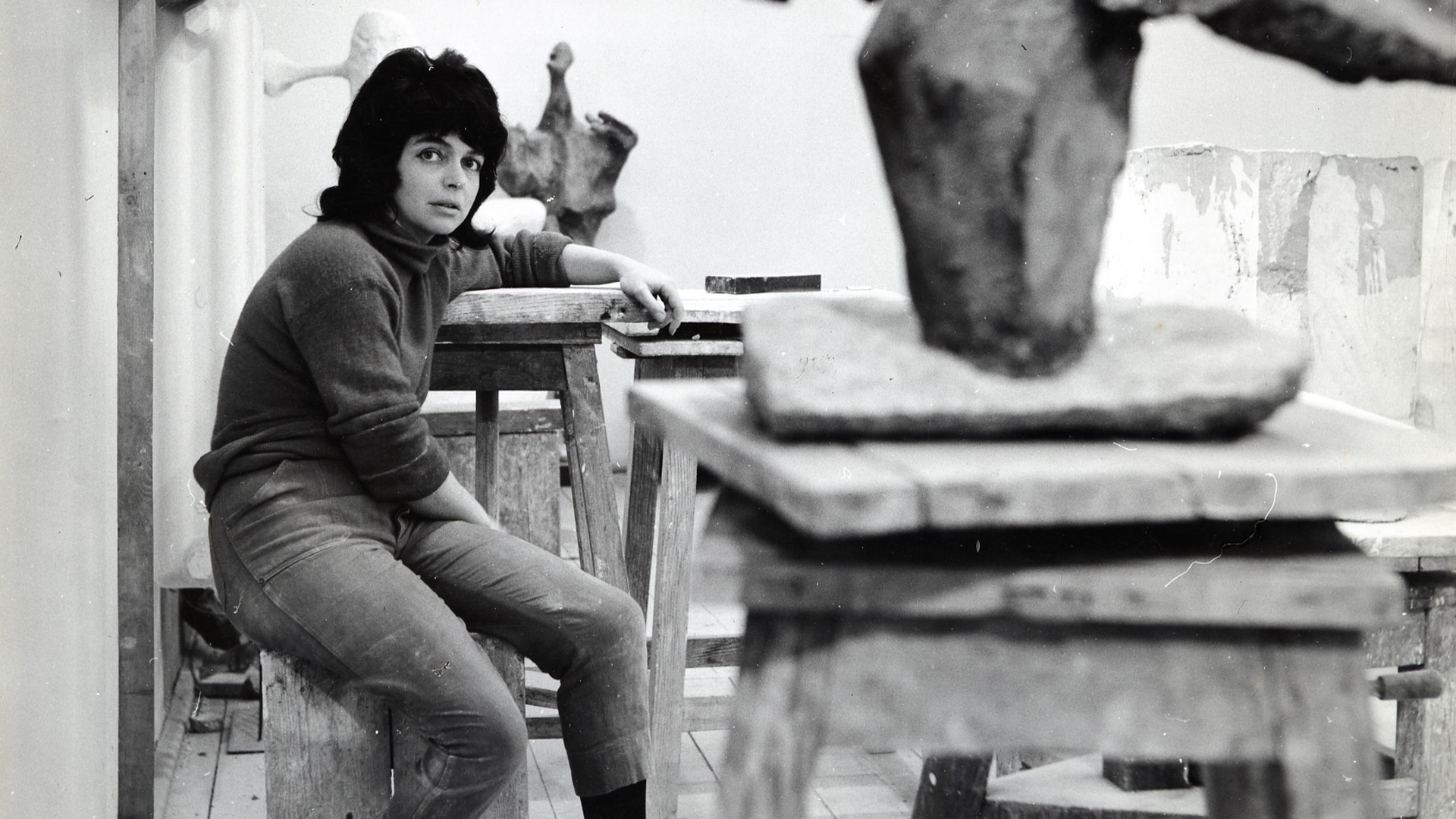

Portrait: Alina Szapocznikow in her studio in Malakoff, France, 1971; Photo: Jacques Verroust; Alina Szapocznikow in her Brzozowa Street studio, Warsaw, 1961. Photo: Wojciech Zamecznik © ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow / Piotr Stanislawski / Loevenbruck, Paris