Louise Bourgeois

Self Portrait

‘Time – time lived, time forgotten, time shared. What does time inflict – dust and disintegration? My reminiscences help me live in the present, and I want them to survive. I am a prisoner of my emotions. You have to tell your story, and you have to forget your story. You forget and forgive. It liberates you.’—Louise Bourgeois

This digital presentation, ‘Louise Bourgeois. Self Portrait,’ invites visitors to explore ‘Self Portrait’ (2009) in great depth through a series of archival images and films, expanding and deepening our understanding of Bourgeois’s significance in 20th century art.

Louise Bourgeois

Self Portrait

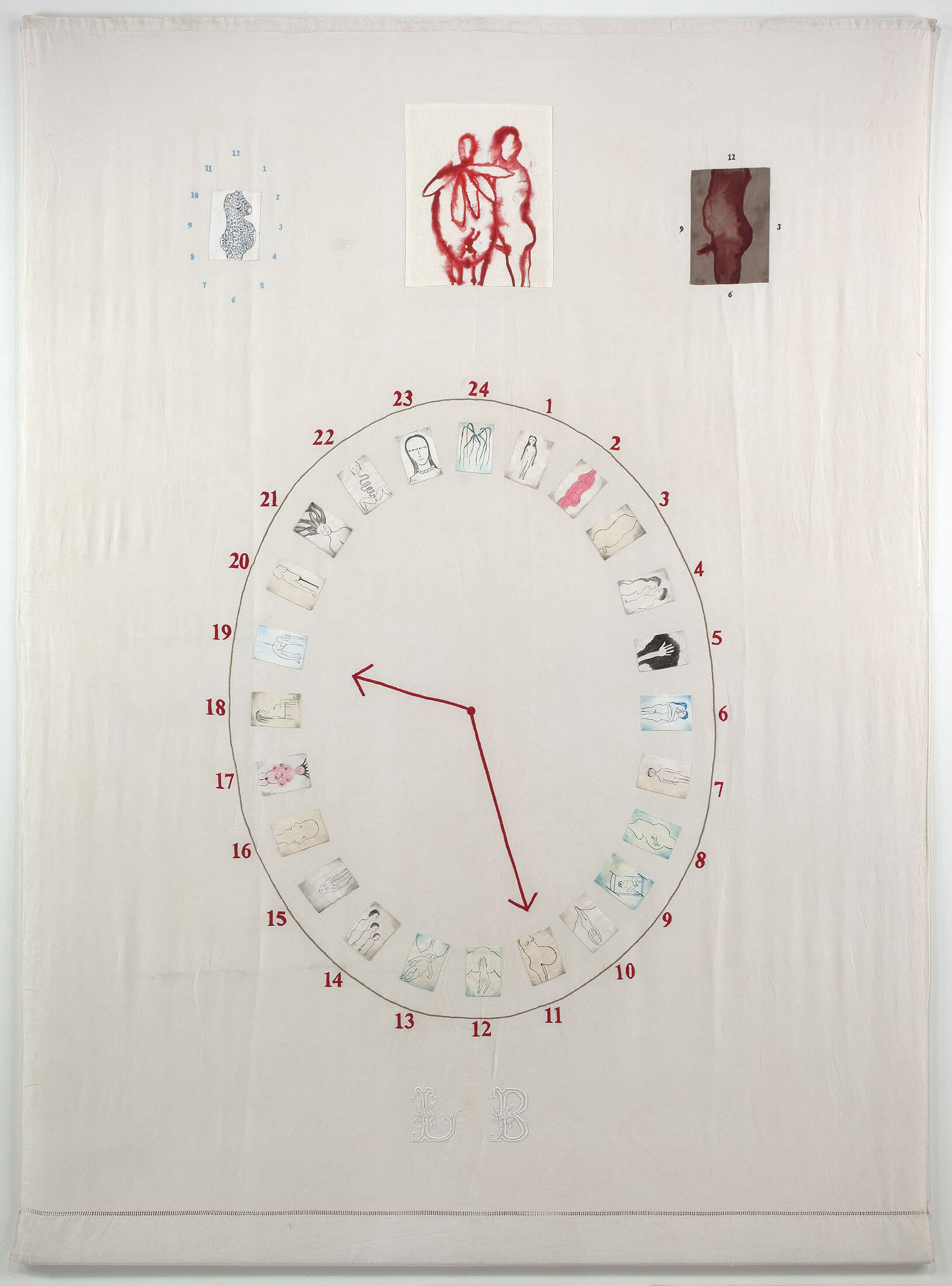

Celebrated French-American artist Louise Bourgeois captured her anxieties, obsessions, and affirmations in a prodigious artistic practice spanning seven decades. This presentation articulates the autobiographical metamorphosis of the artist through her 2009 textile work ‘Self Portrait,’ which depicts a 24-hour clock with its hands positioned at hours 19 and 11 – numbers that together form the year Bourgeois was born.

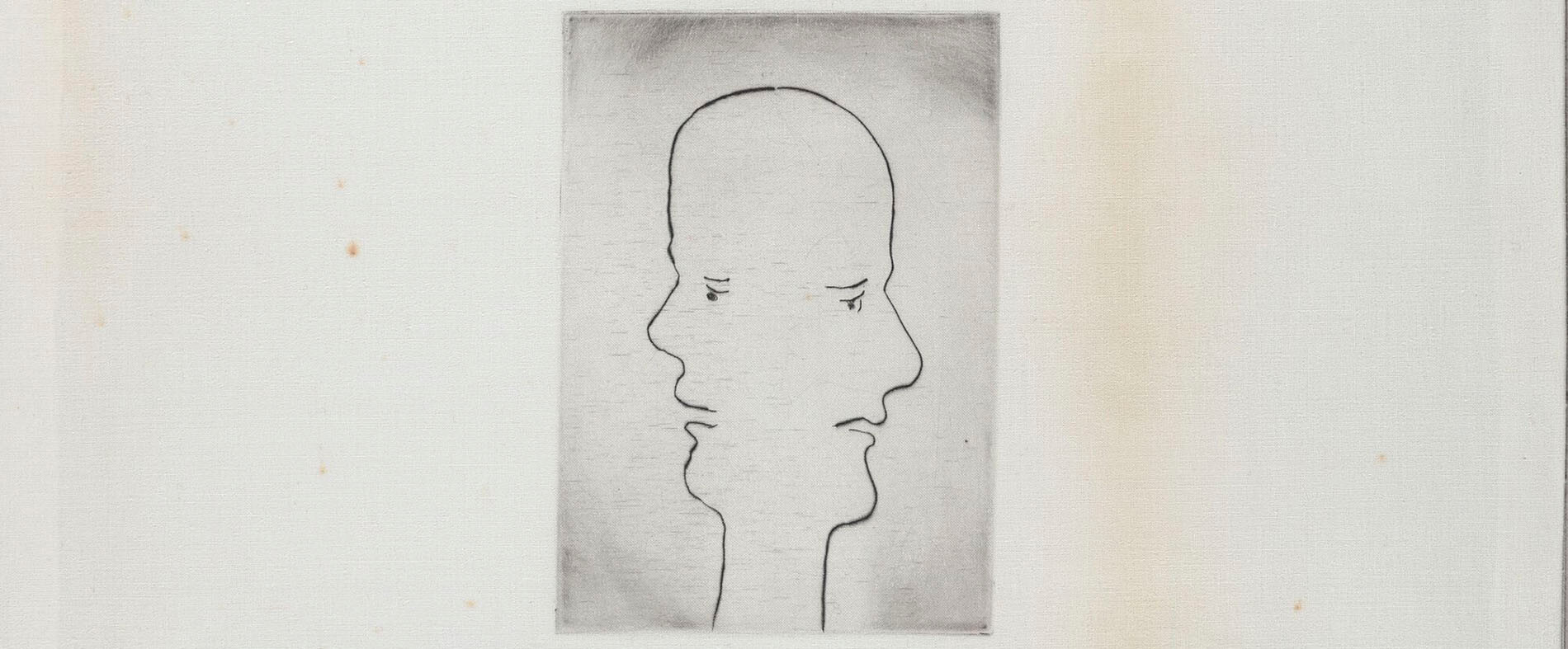

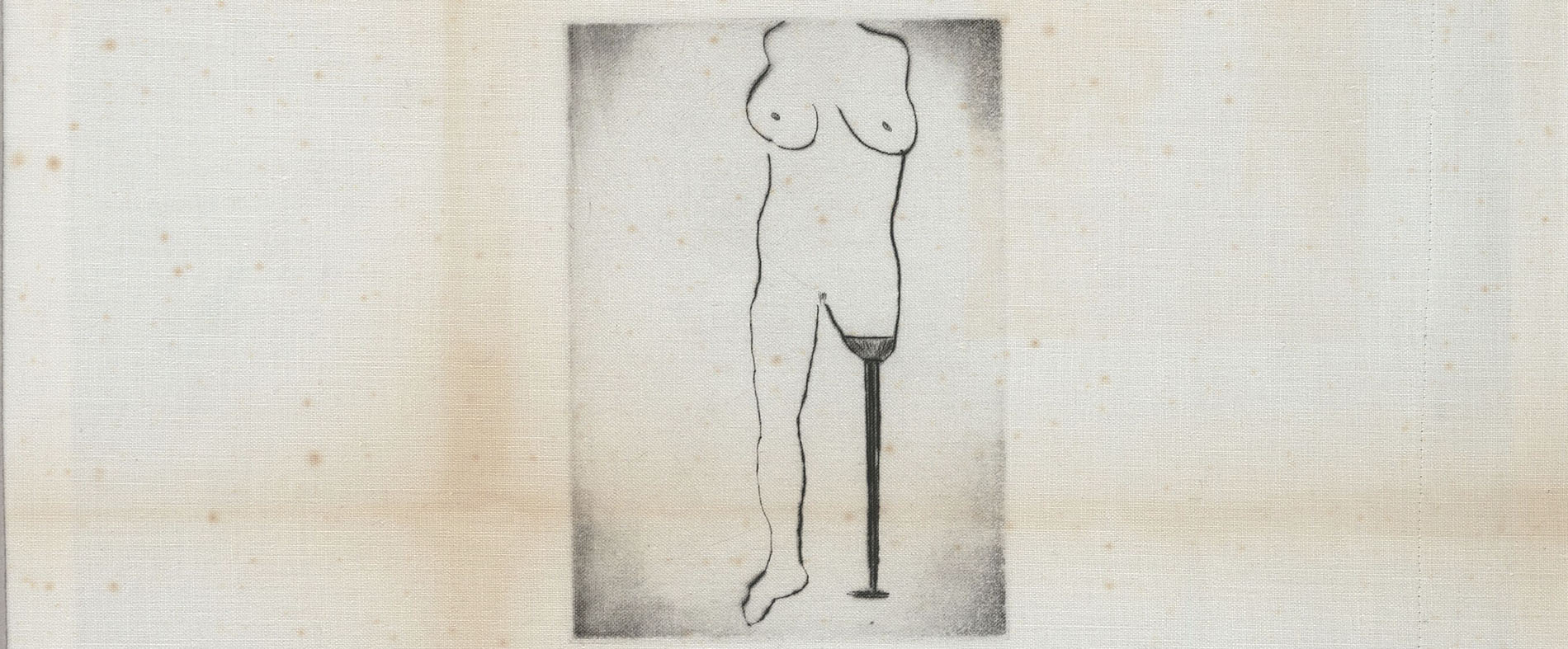

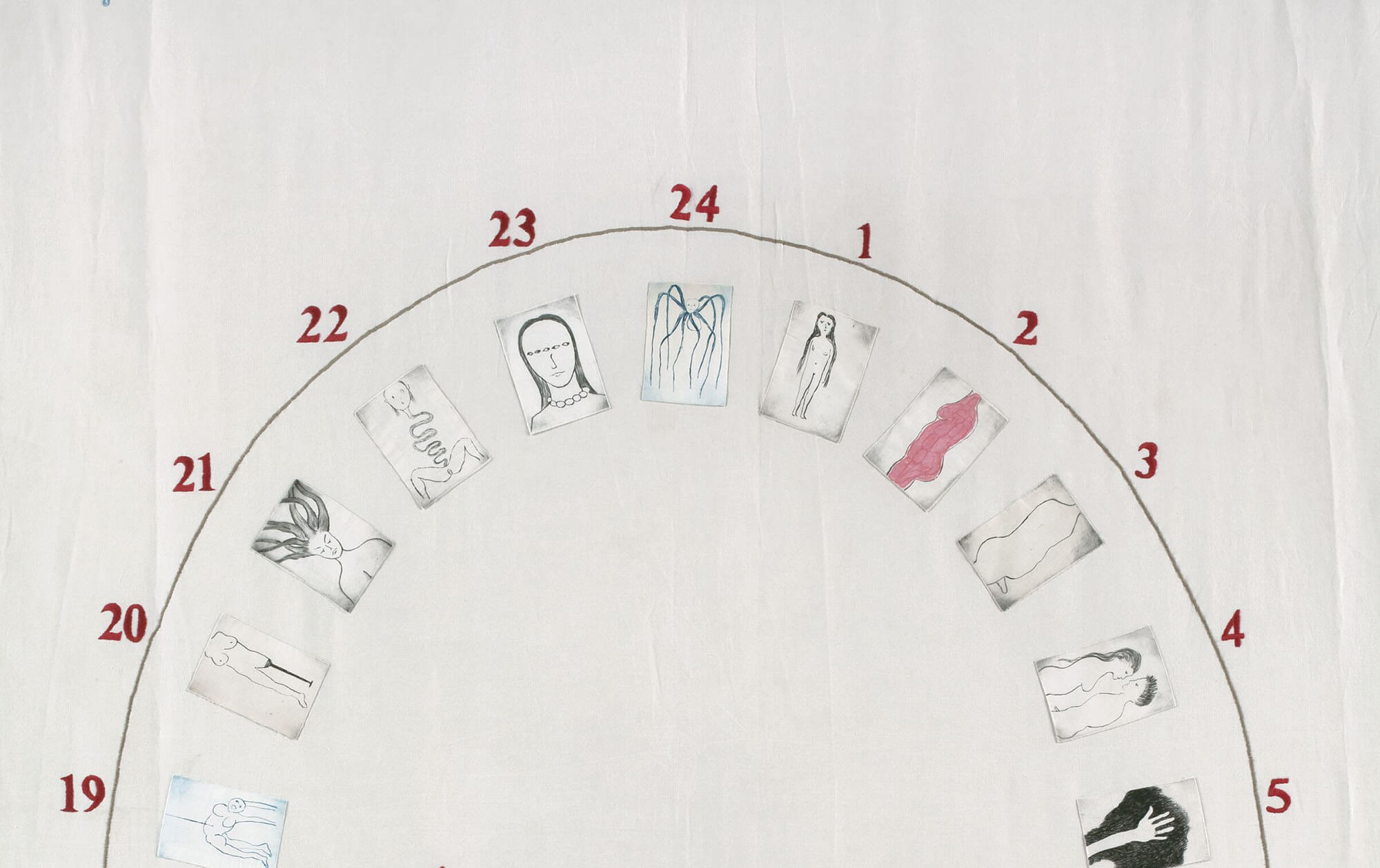

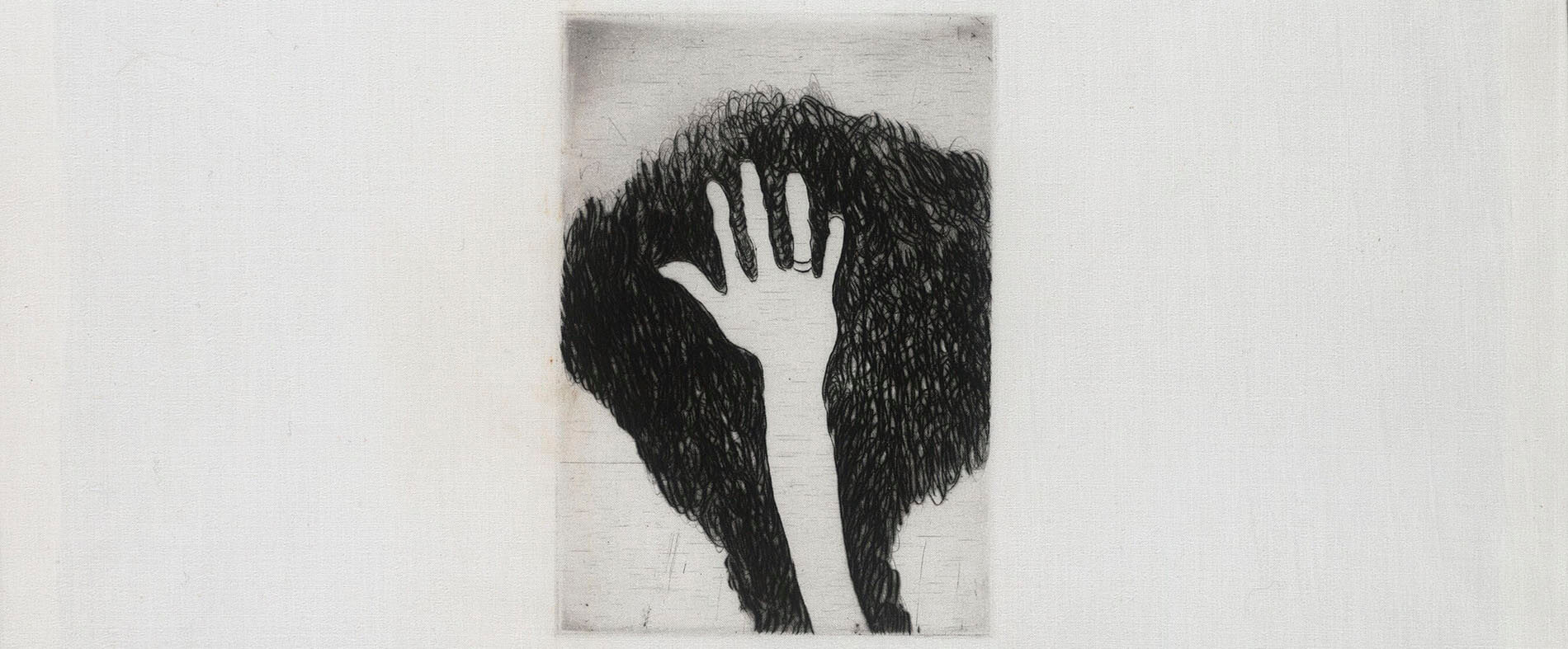

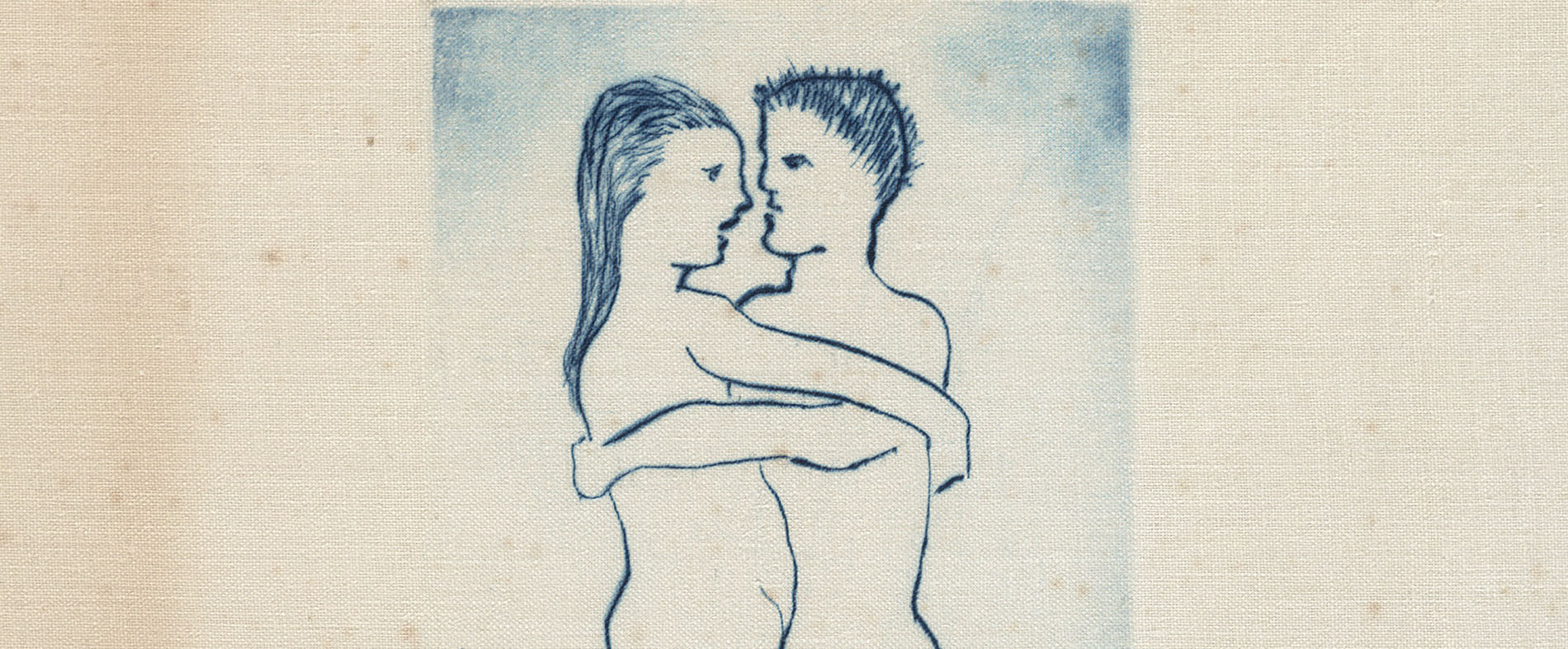

Composed on an old bedspread embroidered with the initials L.B., the twenty-four individually printed drypoint images of ‘Self Portrait’ are collaged and stitched at each hour, marking various events from Bourgeois’s life and symbolizing distinct psychological states and relationships in chronological order. The work is a meditation on the passage of time through a unique visual language in which Bourgeois condenses her memories into images so that together they convey her life story.

‘My life is a succession of quarters of an hour which are spent in a succession of square meters… I’ve schlepped Louise Bourgeois around with me for more than 40 years. every day brought its wound and I carried my wounds ceaselessly, without remission, like a hide perforated beyond hope of repair. I am a collection of wooden pearls never threaded…’ —Louise Bourgeois

‘To make art is to wake up in a state of craving...It’s not a linear progression; it goes like a clock; when you reach a certain spot on the clock, it recurs. It’s a certain rhythm occurring each day. And the making of art has a curative effect.’—Louise Bourgeois

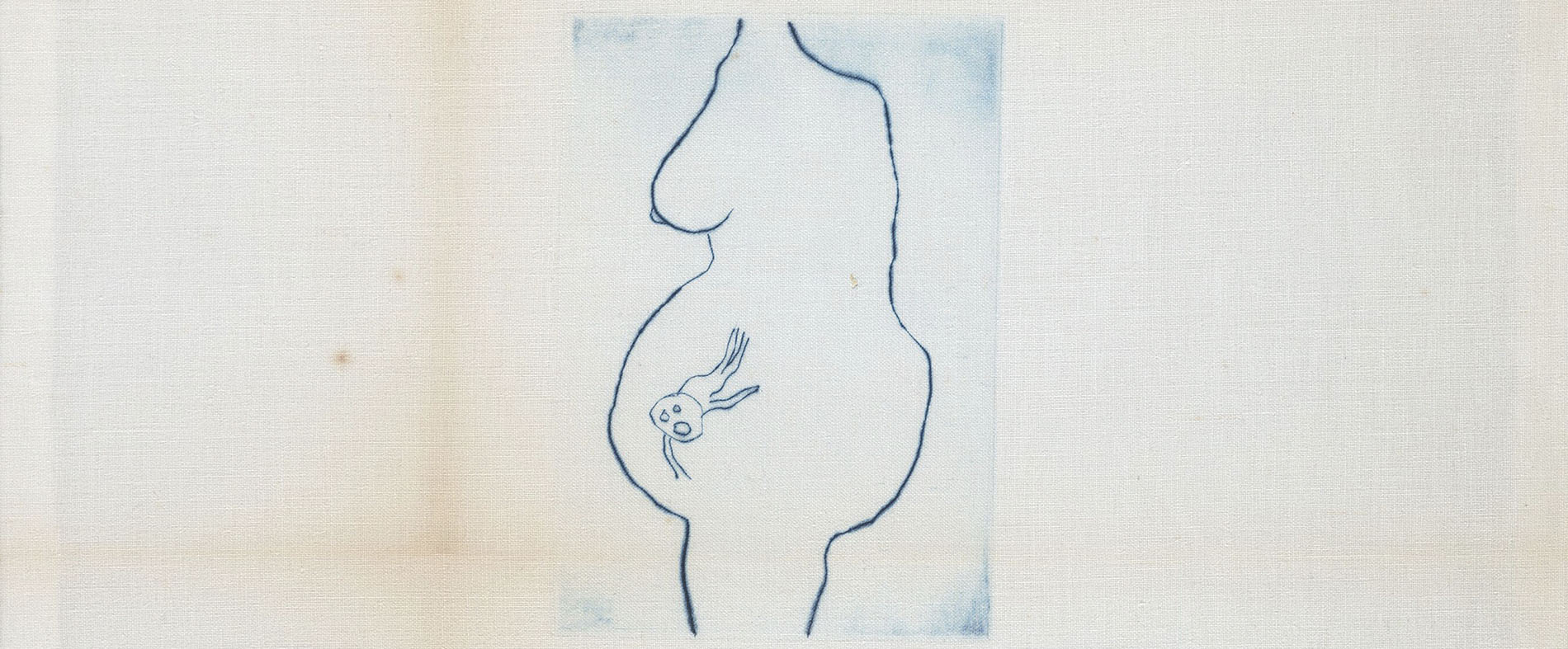

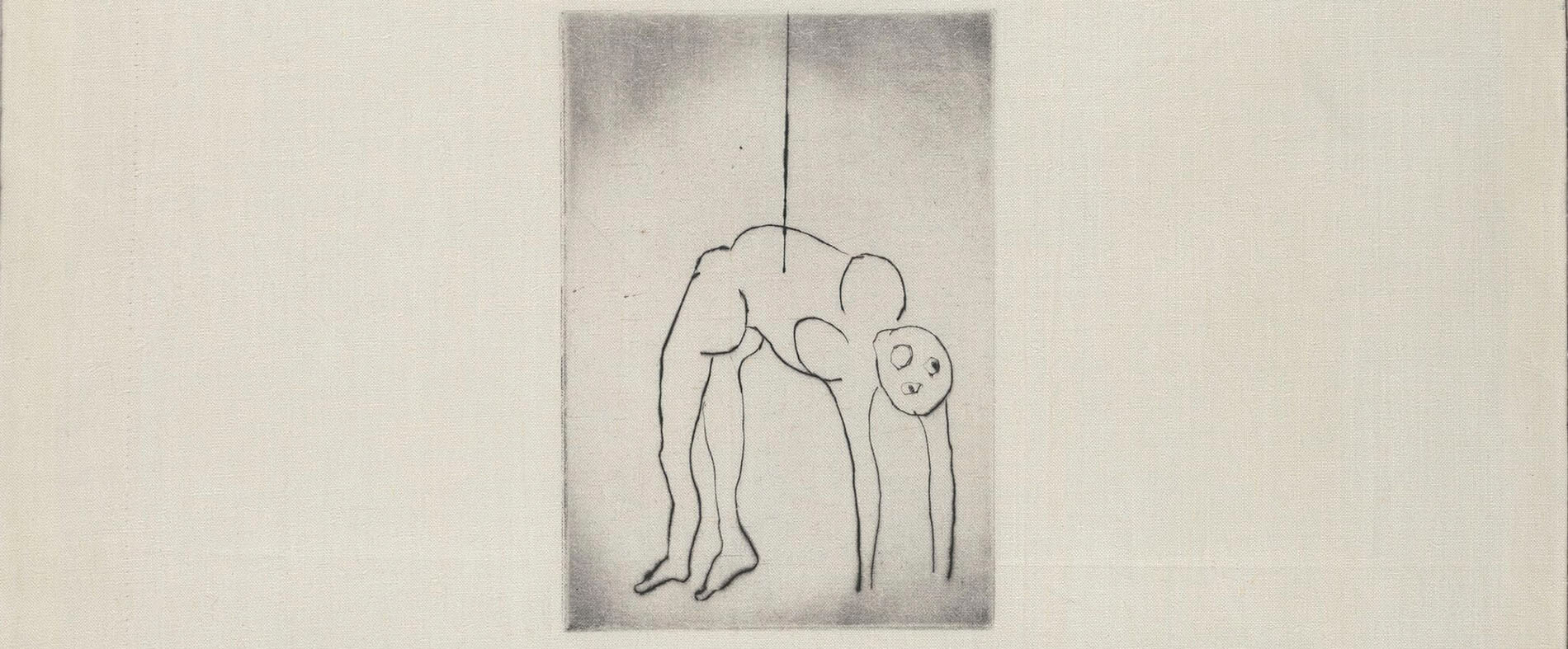

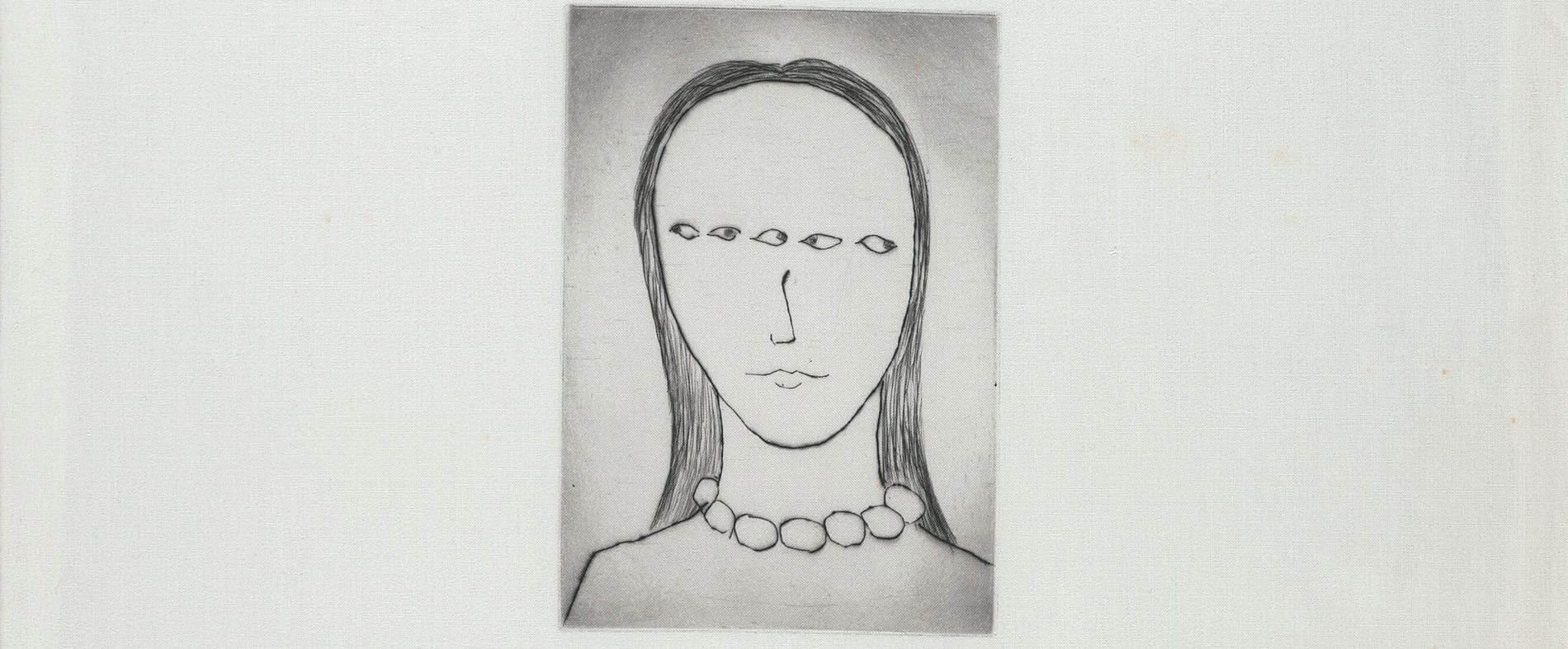

As a girl, woman, wife, mother, and artist, the trajectory of Bourgeois’s life can be traced through her physical and emotional transformation as the hours advance. The first hour shows the artist as a young girl; the following images represent the girl’s rites of passage as she matures, becomes aware of her sexuality, and meets her husband. As time passes, she adopts a child (her son Michel), gives birth to two more sons, and has a family of her own.

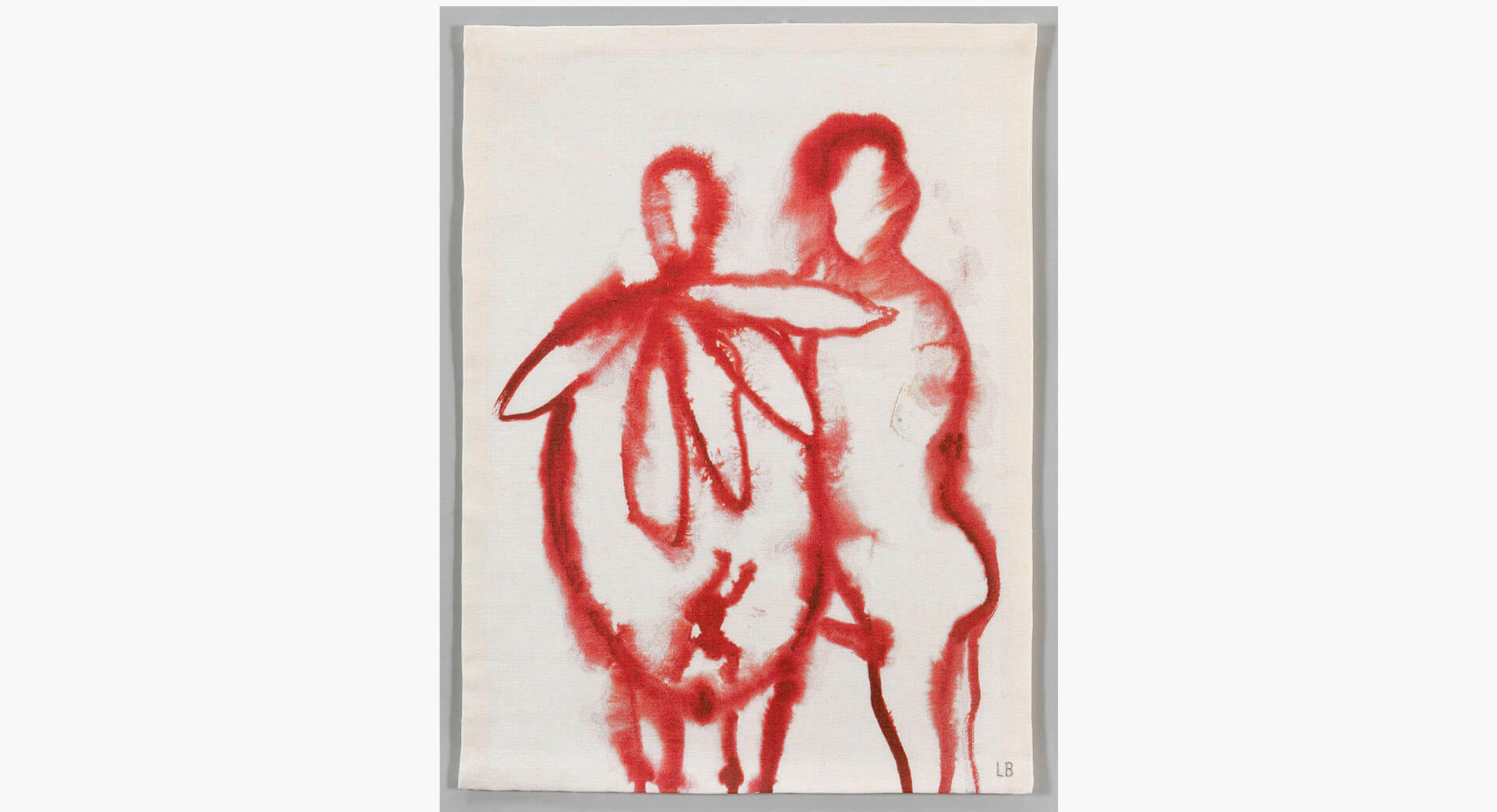

The importance of family is represented by the center panel above the clock, in which the female figure’s five breasts symbolize the family of five that Bourgeois had, while also mirroring the family of five in which she was raised. In this image, she identified herself as the baby in the womb, simultaneously representing herself and doubling back in time to represent her parents.

Bourgeois consistently revisited her past as a means of understanding her present. Here, the formal structure of the clock provides a rhythmic and conscious progression, counteracting the instability of the unconscious and its shifting psychic terrain.

Bourgeois’s psychological states evolved as memories and past experiences were manifested in depression, insomnia, an interest in hysteria, and a deep engagement with psychoanalysis. While some images on the clock are evocative of particular art works, all serve to provide a sense of her life through the imagery she created, instigated by personal feelings of anxiety, guilt, fear, atonement, and reparation, and played out in her relationships with others.

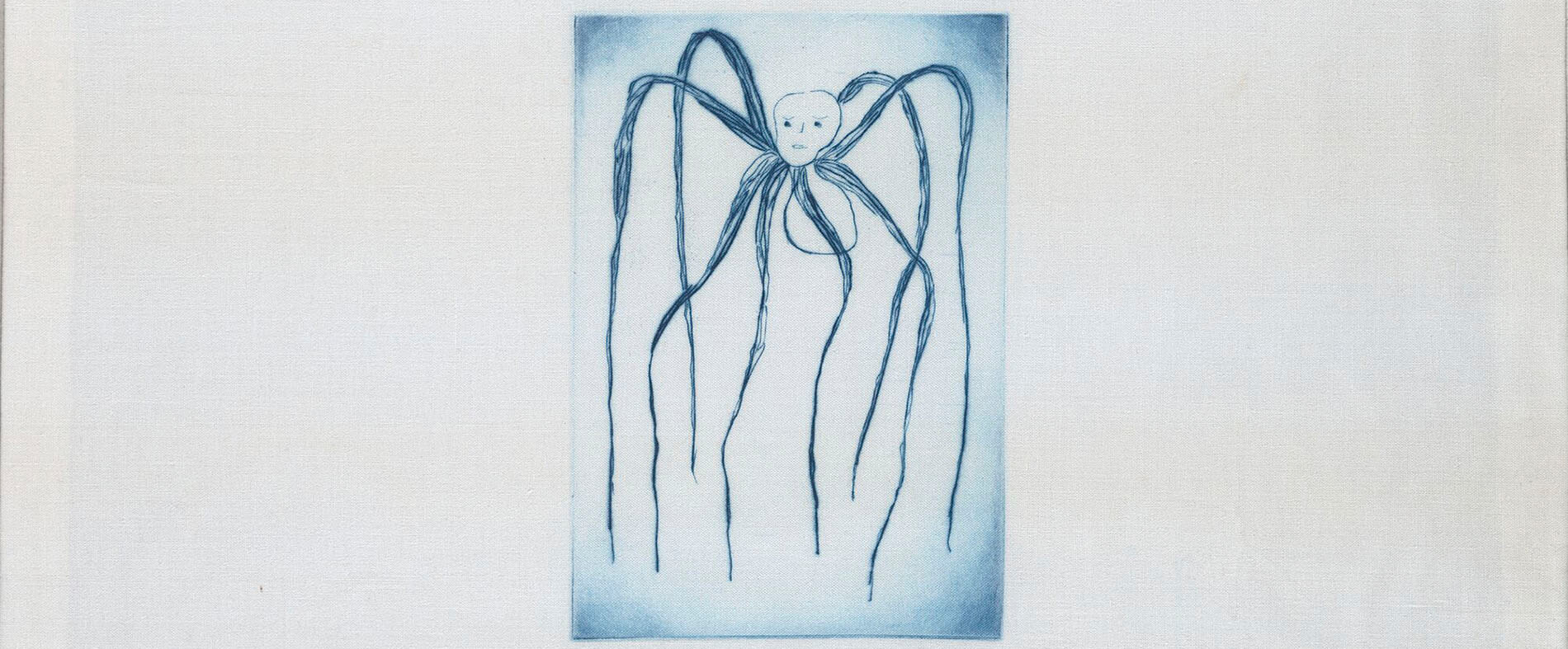

As the clock’s hands return to the top of the dial, Bourgeois depicts herself at the end of her life. The final hour reveals a blue drypoint print of ‘Maman,’ a monumental spider figure symbolic of both Bourgeois’s mother, a weaver, and of her own artistic practice: just as a spider makes its web from its body, Bourgeois felt she made sculpture through her body. By ending with this image, Bourgeois returns to the beginning – to her mother and, ultimately, to the womb, where she will continue again, cyclically, to the young girl.

About the artist

Louise Bourgeois is recognized as one of the most important and influential artists of the twentieth century. For over seven decades, Bourgeois’s creative process was fueled by an introspective reality, often rooted in cathartic re-visitations of early childhood trauma and frank examinations of female sexuality. Articulated by recurrent motifs, personal symbolism and psychological release, the conceptual and stylistic complexity of Bourgeois’s oeuvre plays upon the powers of association, memory, fantasy, and fear.

Photo: Louise Bourgeois in Le Cannet in 1928; All images © The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at ARS, NY