Conversations

The Shape of Words

A conversation with Julie Sylvester about John Chamberlain’s lesser-known works of poetry

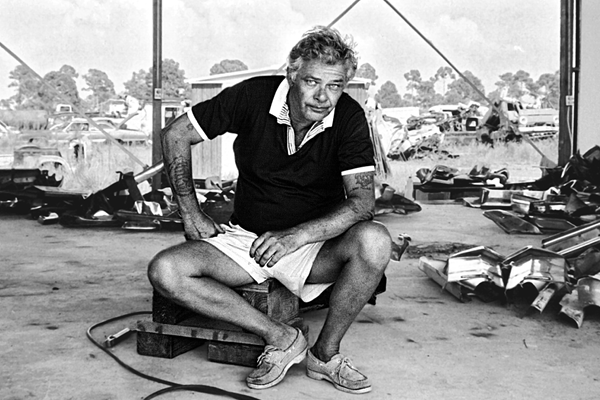

Chamberlain in his temporary living quarters and studio, Glueck’s Auto Parts salvage, Osprey, Florida, 1980. Photo: Marcia Corbino

Celebrated for his path-breaking sculptures made from discarded automobile parts, John Chamberlain also had a longstanding artistic engagement with language. After spending three years in the US Navy during World War II, Chamberlain enrolled in the Art Institute of Chicago and then Black Mountain College, where he developed the critical underpinnings of his work. It was in North Carolina in the early 1950s at Black Mountain where the artist wrote experimental poetry. In the 1980s, he gave these relatively unknown poems to curator and author Julie Sylvester, and she published these for the first time in original form in Black Mountain Chamberlain: John Chamberlain’s Writings at Black Mountain College, 1955 (2020).

Chamberlain’s love of language is present in the titles of his sculptures, which were assembled based on “fit.” His later series of Gondola sculptures were each named after notable poets. On the occasion of the exhibition, “John Chamberlain. The Poetics of Scale” at Hauser & Wirth Monaco, Sylvester spoke with Tanya Barson, Senior Curatorial Director at Hauser & Wirth, about Chamberlain's unique approach to language, materials and scale.

Tanya Barson: I think it would be really good to begin by understanding your role in this story around John Chamberlain and his poetry. How did you first come into contact with Chamberlain? And how was it that his poetry came to surface so many years after they were written?

Julie Sylvester: Basically, no one knew the poems existed except for those who saw them at Black Mountain [College, North Carolina]. I didn't know anything about them. Clearly they were important to John, which is already very unusual, because almost nothing [in terms of his archive or documentation] was important to John. But for some reason he really held on to these poems, all together, very neatly preserved, which was not a characteristic of his at all.

At that time John and I spent an awful lot of time together. I worked on the catalogue raisonne over seven years, we lived a few blocks from each other and I was always over at the studio. He had a shoebox with some polaroids of pieces. He didn't know what they were called. He couldn't remember when he made them. It wasn’t that he didn't remember anything, but among all of the information that John had at that time, absolutely nothing was well taken care of, except for these poems, which I had no idea existed, until one night he showed them to me.

At some point a little later, he gave them to me, the entire collection. I didn't think that much of it at the time. But of course now I realize, 30 or more years later, that it was quite a good thing that he gave them to me, because they could have so easily been misplaced, or people might not understand what they were, or that John had even written them.

I always think of the way that Louise Bourgeois kept all of her sculptures in storage for decades, when nobody was even interested in looking at them. Nobody was asking her about them, nothing. But she kept them in storage, diligently paid for the storage and maintained them because she knew they were important.

“Black Mountain was the first place that he felt that he was understood and where he understood the people around him. The first time.”—Julie Sylvester

A poem written by John Chamberlain at Black Mountain College, 1954 – 1955

Julie Sylvester, John Chamberlain and Donald Judd at an airfield in Marfa, Texas

TB: It’s such a large group of poems, it was obviously something he was quite preoccupied with whilst at Black Mountain. He was creating text-based work there, which we can think about in relation to his later work, and it gives us something concrete from that time that he spent at Black Mountain College, as well as pointing towards what possible later relevance they may have had for his visual art.

JS: It was the only thing that interested him at the time. I don’t think he ever thought that he would be a poet, because he could see the difference between what poets were doing and what he was doing, but I think he saw that it was really a lot of fun. He respected the people he was with and I think he very quickly realized that it would be useful.

TB: Charles Olson and Robert Creeley were among the poets he associated with at Black Mountain. Did he maintain any of the relationships that he established while he was there?

JS: Yes, he was friends with Robert Creeley his whole life, and I got to know Robert Creeley quite well towards the end, too. But he was the only one. John didn’t preserve so many old friendships. He wasn’t an alter ego, but Creeley offered some kind of balance for John.

TB: Chamberlain is one of the ground-breaking sculptors of the twentieth century, considering the variety of new mediums in which he experimented. He was also, it seems, a big personality. When he gave the poems to you, was he nervous about sharing them? It’s a highly personal body of work after all.

JS: He was never nervous at anything. I think he really gave them to me as a meaningful gift. I mean, we were very close and spent a lot of time together. I was in Sarasota for weeks at a time, and we went to Marfa together quite a bit. We were very comfortable hanging out together, even though there was a big difference in age. All of that quickly disappeared. We liked each other. So it was an intimate gesture.

But it’s also important to remember that at Black Mountain, John had just gotten off a battleship. He was a sailor in the Pacific during the Korean War. He then went to Chicago where he became a hairdresser on the G.I. Bill. I just imagine all of these things in 1954. A big macho man like that learning to be a hairdresser. He was so incredibly flexible and fluid that I don’t think he ever felt a place where he was uncomfortable. He said that Black Mountain was the first place that he felt that he was understood and where he understood the people around him. The first time. So that’s kind of the beginning of everything, that that one very short year at Black Mountain.

Founded in 1933, Black Mountain College brought a new model for the arts education to the United States. Courtesy Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina

A poem written by John Chamberlain at Black Mountain College, 1954 – 1955

TB: It was also a time when Black Mountain was coming to the end. It was a time when the school was dominated by poets, by Olson as well as Creeley that we’ve mentioned. So we’re talking about a very specific moment in the history of Black Mountain College?

JS: Yes, as John said, it’s the year that things started to fall apart. There was no school the following year. So he was there at the loosest, most chaotic time, which would have suited him perfectly. What I like in the poems is just the color and flavor of the time and of the South. The South was new to John, and you can hear it in his description of things, and in how he’s saying things he hasn’t seen before.

TB: I think what’s interesting for me is that you get these quite vivid images from the poems. There are human relationships there. There are observations of weather and the feeling, the real bodily feel of weather as well, there’s a palpable sense of landscape and environment that you get from them. I think there are many different layers, but recurring themes within them. Another recurring theme is artistic production itself. There are some which mention other artists, particularly sculptors. There are some very evocative images within these poems.

JS: Yes, I think so too.

TB: I think somehow all of these components that we find in the poems recur in his sculptural and broader artistic practice, albeit they come back in different forms. There are different ways that that happens. The materiality of words is one thing, and the breadth of the idea of material itself, that color is material which is so important in his work, but also this idea of fit…how things including words fit together. Is that something that you see? Do you think it is one of the valuable parts of this this body of poetic works?

JS: It’s central to everything. John says it in in the interviews [I made and included in the catalogue raisonne] quite directly. He said it was there [at Black Mountain] that I learned, by putting words together, I learned how to make sculpture. I learned how to fit pieces together, things that wouldn’t necessarily fit together, to make them fit. And if you look at the structure of the poems, and you look at the early sculptures, there it is, right there, and he never abandoned that. That was always the way he worked in in every medium.

For instance, the Plexiglas pieces he did with Larry Bell. They were totally experimental, like “what would happen if I did this?” And the most beautiful sculptures of John’s, I think, are the galvanized pieces, the crushed “Judd” boxes. They’re so elegant and so extraordinary! Who would think of crushing Donald Judd’s precious, though rejected, sculptures? His galvanized pieces were made from things that Judd considered to be imperfect. If you look at them now, they’re some of the most elegant pieces. Cy Twombly had the most beautiful one, which was a small galvanized piece that looked like an Aphrodite or something. Of course he picked that one. It’s just beyond elegant. And John could do that with any material. From his point of view, poems are just the same. It’s just another material.

John Chamberlain, Untitled, c. 1967. Cy Twombly Foundation © 2023 Fairweather & Fairweather LTD/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Peter Schälchli, Zurich

John Chamberlain, Hano, 1970 © 2023 Fairweather & Fairweather LTD/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jeff McLane

“Poems were maybe the first things that John really made, that he called his own and was proud of.”—Sylvester

TB: From your perspective as editor of the catalogue raisonne, do you think any particular series of sculptures resonate with any specific poem?

JS: It’s everywhere, because poems were maybe the first things that John really made, that he called his own and was proud of, which is confirmed by the fact that he signed one or two of them. He made titles for all of his sculptures, you cannot find an untitled piece, and every title is hilariously funny, clever, or in reference to something. They are all like tiny poems. That never stopped until he started making small things, called the Tonks and just numbered them, but up until then, everything has a title.

When I was with him in the studio, it would take him with the longest time to come up with titles. He would always write everything down. It was very visual. And he’d say, “what do you think of that, Sylvester?”

TB: They’re very evocative titles. They are word images as well as the poems. There is a direct line between these poems and the way that he titles the works.

JS: Absolutely, and they’re everywhere, in everything, over decades. So the poems are never really lost, if you know that they exist.

TB: Thinking about the transition from the poems to Shortstop (1957), his first crushed metal piece, there’s the shape and sound of the title Shortstop?

JS: Yeah, which has so many references to so many things.

TB: And alliteration. I mean he obviously played with the sounds as well as with the shape of words, and with the resonances and the evocations of what he’s using, evidently thinking all of these things as his material.

JS: When came up with a title, he would write it down—he had great handwriting—and he’d say, “How does that look? How does that sound?” So that’s poetry. It’s not like, you know, sunset on the West Side highway or something. Not that he pulled them out of thin air. I think he thought they were worthy of having titles. And then he could abandon them. But he kind of liked to finish things off. It’s a strange kind of perfectionism.

When I did the catalogue raisonne of the sculptures there weren’t even computers. I had baskets with folders, with all of the pieces in them. Now it’s very easy to collect all of the material and put it together. I think it’s very, very important to do it, and I think it has nothing to do with the authentication or anything. I think it’s just that a clear document has to be made.

Installation view, “John Chamberlain. The Poetics of Scale,” Hauser & Wirth Monaco © 2023 Fairweather & Fairweather LTD / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

TB: It’s about showing a really expanded picture of all his practice, right? The different bodies of work. Do you think that these poems are a kind of trigger into reviewing the rest of his career and showing it to have the breadth that it did?

JS: Absolutely. I think they’re a priceless gem of art history. I mean, they’re kind of the key to Chamberlain, but especially since nobody knew they existed, and in the past five, or ten years there has been so much hype about Black Mountain. But nobody ever talks about John. It’s quite simply because nobody knew that he was there, or that he wrote this body of poems. A couple of people there knew. His wife Elaine knew. That’s about it until he dumped them in my lap one day.

I organized a huge retrospective in ’86 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. It was a huge, huge show, and there’s never been anything like that since that encompasses all of the things that John did through throughout his life. There just hasn’t. There was a huge barge foam sculpture with his film The Secret Life of Hernando Cortez playing on monitors at either end. It was shut down by the mayor of Los Angeles as pornography. But it’s just endless. It’s not just rooms of static sculpture. And so, if the catalogue raisonne were to be done now, I think it should just go strictly chronologically and take big, big pauses for these other interludes in between his better-known sculptural works.

TB: Because then you would have this picture of the overall complexity.

JS: You would really have John Chamberlain, not just John Chamberlain’s sculpture, but his larger career. He was an enormous personality and figure, and you don’t get all of that by just looking at the sculpture.

–

Julie Sylvester is a curator and author who, in addition to John Chamberlain, has worked closely with artists including Louise Bourgeois, Cy Twombly, and Willem de Kooning.

Tanya Barson is Senior Curatorial Director at Hauser & Wirth. She was formerly Chief Curator at MACBA, Barcelona, and Curator, International Art at Tate Modern.

Black Mountain Chamberlain: John Chamberlain’s Writings at Black Mountain College, 1955 was edited by Julie Sylvester and published by Princeton University Press in 2020.

Organized in close collaboration with the John Chamberlain Estate and curated by Tanya Barson, “John Chamberlain. The Poetics of Scale” is on view at Hauser & Wirth Monaco from 10 May to 2 September 2023.