Conversations

Hip-Hop’s Dead Sea Scrolls

Carlo McCormick in conversation with Pete Nice about the birth of a musical movement and its founding documents

Flyers and posters courtesy Pete Nice. Photo: Carlo McCormick

If hip-hop—perhaps the last great cultural movement of the 20th century, a source of constant innovation and continuous reinvention—did not have a resident fanatic and self-appointed scholar like Pete Nice, it would surely have had to invent him.

As a boy growing up in Brooklyn and Queens, Nice (born Peter J. Nash and known during his own hip-hop career as Prime Minister Pete Nice) had some lucky exposure to the nascent sounds of early hip-hop. He became a passionate fan, one with deep-seated packrat tendencies from an early age, focusing on both musical and baseball ephemera. Next, he transformed himself into a successful and credible MC as part of the seminal white rap group Third Bass. And then, in a kind of second act, he became a devoted collector, researcher and self-taught historian, one who now serves the curator of the Universal Hip Hop Museum, a vast collection of rare memorabilia scheduled to open to the public in 2024. Over the years, Nice has tended to the legacy of hip-hop as something like a gardener, forever digging in the weeds, saving heirloom seeds whenever he finds them. Along with Paradise Gray—a fellow historian who managed the Latin Quarter, the legendary Midtown club that became a mecca for hip-hop in the 1980s—Nice has been working with a wider community of collectors to try to build a definitive archive of hip-hop flyers and posters.

A relatively humble authority, Nice comes off as confident but curious, obsessed, like all serious collectors, in finding things but ultimately more interested in making sense of what he has. He brings a remarkable eye to the iconography and coded messages of flyers, cards and invitations, locating adjacent components of music, dance and art that converged to form the movement’s distinctive brand of DIY advertising and promotion— explicating, for example, the foundational role that early graffiti artists like Phase 2 and Riff 170 played in making flyers for hip-hop artists, as well as highlighting the significant contributions of other artists like Fab 5 Freddy, Futura, Eric Haze, Cey Adams and Keith Haring. Nice can point to rare documents that show how and when sneakerpimp culture formed around local club events. “All these things became billion-dollar industries,” he says. “And in the end all you have left are some sneakers, flyers and drawings to collect.” I asked him about the worldwide celebration now occurring for hip-hop’s fiftieth anniversary, suggesting to him that the definitive founding year seems like a corporate concoction, basically pulled out of someone’s ass to better monetize the history. Nice, a baseball-history fanatic, agreed and reminded me how the centennial of baseball’s founding, celebrated in 1939, was purely a marketing invention, driven by Cooperstown, the Spalding company and the whole-cloth myth of Abner Doubleday’s “invention” of the game. The founding year of 1973 for hip-hop, he says, is as much of a fanciful fabrication, based on an invitation for a Kool Herc “Back to School Jam” on Sedgwick Avenue in the Bronx that some believe might not have happened at all. As he was saying this, he showed me an invitation on a filing card for another Kool Herc party—in 1972. Like most great cultural movements, hip-hop germinated and grew organically, making it next to impossible to pin down origin stories or fixed dates. By the same token, you could also say that it has no expiration date.—Carlo McCormick

1981

1980

1980

1978

Carlo McCormick: You have a long history with hip-hop, but let’s begin by just talking about you as a collector. You also were a big sports memorabilia collector before this.

Pete Nice: My family was originally from Brooklyn. I lived there when I was really young and then we moved to Queens. As a kid, you collect baseball cards, comic books, you know, and there was this little spot on a corner near where I lived, behind a bar called Woody’s, where an old guy had coins, baseball cards and stamps, and I would go there every week with my allowance. We’d also go on family vacations to the east end of Long Island, and my mother was into collecting stuff, and I would go with her to antique places out there. That’s how I got into it, and it got to a point where I would collect anything as long as it was old. Then I got a bit more obsessed with sports, particularly baseball, and I would write to old-time players when I was nine and ten years old. One of the guys I became pen pals with was the pitcher Waite Hoyt, who was on the 1927 Yankees along with Babe Ruth. It was Hoyt and a lot of other eighty-year-old men who taught me my early history. Then I became really interested in Negro League players and joined the Society for American Baseball Research. I was maybe twelve years old and here I was on a committee to advocate for Black players being included in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Part of all that was also about collecting autographs.

McCormick: I’m curious about this connection between your collecting obsessions as a kid and this remarkable archive you’ve built as an adult. Getting to the pathology here, is it about the stories these objects tell for you or more a kind of physical fetish?

Nice: My dad grew up right by Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, and I just always had a romanticism for the old days. Once you track down a whole bunch of baseball cards from the ’50s, you go: “Oh wow, how about the ’40s?” And you keep going back and back. It becomes an H.G. Wells time machine, and I appreciate that aspect of it now more, being older. But as far as hip-hop went, there really seemed to be nothing out there to collect. Back then, I was too young to be going up to jams up in the Bronx to get flyers. Probably the first flyers I came across were from 1985 and 1986, and those were the first ones I saved. A friend of mine and I rode our bikes up to a club on Jamaica Avenue called the Encore. We didn’t get in. It was like a ten-dollar cover. But we got the flyer. It was a Rush Productions show, with Kurtis Blow and a bunch of other great acts.

McCormick: You have a really early Rush Productions flyer in your collection, and it’s remarkable to see how Russell Simmons was pretty much killing it right out of the gate. Weren’t you also on Russell’s label Def Jam?

Park jam in the Bronx, New York, early 1980s. Photo: Henry Chalfant/Art Resource, NY

Nice: Yeah. I got signed by Russell as a solo around 1988. Dante Ross brought him my demo tape. MC Serch was also there, but we were doing our own solo projects, and it was a good year or two before we started working together. Sam Sever, who had worked with Beastie Boys and produced a lot of great tracks, was working with both of us individually, and he and Dante saw these two white solo artists who weren’t doing all that well, and they had the idea to put us together. And then they tried to sell us to a major label, but everyone wanted us to be the next Beastie Boys, another rock/rap fusion. Of course, a lot of people didn’t want to get anywhere near us. There just weren’t a whole lot of white MCs, DJs, dancers or the like in hip-hop back then. We were as rare as the dodo bird.

McCormick: As a collector, how did you get back to the earlier days of hip-hop, the way you were able to do with baseball? These flyers were hardly mass-produced the way baseball cards are.

Nice: A lot of it came about because I played basketball in high school. My dad had been a coach at Stevenson High School up in Soundview in the Bronx, and he worked for the Big Apple Games rec league, where I worked as a ball boy. I was able to connect to a lot of schools where some of the first jams and parties took place. I even had a summer job working at welfare hotels like the Brooklyn Arms and the Harlem Hotel. I just knew a lot of different people. That’s where I would first hear the music. It wasn’t about records then. It was people playing mixtapes, so you wouldn’t know exactly what you were hearing, but in retrospect I can still remember the breaks from Bob James’s jazz hit “Nautilus,” one of the most sampled songs in history, and hearing the Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, who were first called the L Brothers. I remember songs like Cerrone’s “Rocket in the Pocket” on tapes I heard in the ’70s. That’s how I got into the music— going to the jams in the parks, not in the clubs, because in 1979 I was twelve years old, and then Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” hit and boom. It’s all over the place, everywhere

McCormick: Were the flyers up in the record store?

Nice: That didn’t start happening until the late ’80s, early ’90s. Phase 2 told me that the early flyers were mostly handed out to people. The promoter Van Silk started out handing out flyers for Kool DJ AJ. Though I noticed it then, I didn’t really think about how sometimes there was a blue flyer and sometimes a pink flyer, and Van told me the pink ones were handed out at girls’ schools and the blue ones at boys’ schools. There was a guy up in Mount Vernon who did a lot of the offset printing for them, with colors and all sorts of stuff. A lot of the early promoters of disco were doing shows at Madison Square Garden with Grandmaster Flowers and Brooklyn DJs, and the disco promoters already knew the poster game, so the knowledge got passed on. For the kids up in the Bronx doing shows in the parks, posters weren’t initially a big thing and didn’t come in there until later. Clubs like Harlem World, on 116th Street, did posters, but not many of them survived.

1982

1980

1979

1979

McCormick: There’s a surprising narrative that you can read through your collection, which is that it seems like disco basically turns into hip-hop.

Nice: If you look at the flyers, you can see how early on, hip-hop is referred to as disco, or maybe they were talking more about disco as a place, not the type of music. The term “MC” doesn’t get memorialized on a flyer until 1978, so that’s the year of the MC, when Grandmaster Flash had three MCs—Cowboy, Kid Creole and Melle Mel—and that’s when guys were actually rhyming on the beat, the way we know it today. It was a significant change from earlier, when DJs were saying lines. You see flyers from back as early as 1976 saying “Battle of the Rappers.” But that’s more like guys on the radio saying their slick lines. There were guys like DJ Hollywood—and if you ever tell anyone he’s not hip-hop, Doug E. Fresh will school you for an hour. You can see what Hollywood was doing from what’s on the flyers and tickets. He would have a whole crowd in the palm of his hand, doing four or five spots a night and making $500 at each spot. He would go in, do his routine for half an hour or forty-five minutes. He would do call-and-response and he would also do his rhymes. But it would be over disco records, not over hard-break beats or scratching. There are so many controversies and disputes about this. That’s why the flyers are cool, because they give some sort of evidence of what was actually happening.

McCormick: Did Kool Herc have flyers for his earliest shows?

Nice: There are Herc flyers, but at the beginning there were just index cards that he and his sister, or the girlfriend of the guy throwing the party, would write out with basic information and hand out to people. There were house parties, rec-center parties. There’s a flyer for Herc, done with offset printing, for a party he did at a spot on Jerome Avenue called the Twilight Zone, and that’s 1974. So they did move on to flyers early. Riff 170 was doing flyers for Herc around 1975, and that’s even before Phase 2, who told me about a guy named Kareem who was doing flyers even before that. Coke La Rock, who was part of Herc’s Herculoids back in 1973, talks about Riff making a flyer that showed him standing on a building like Godzilla and that Riff went into Coke’s bedroom and painted the image on the walls with Day- Glo paint so that you could see it when the lights were turned off.

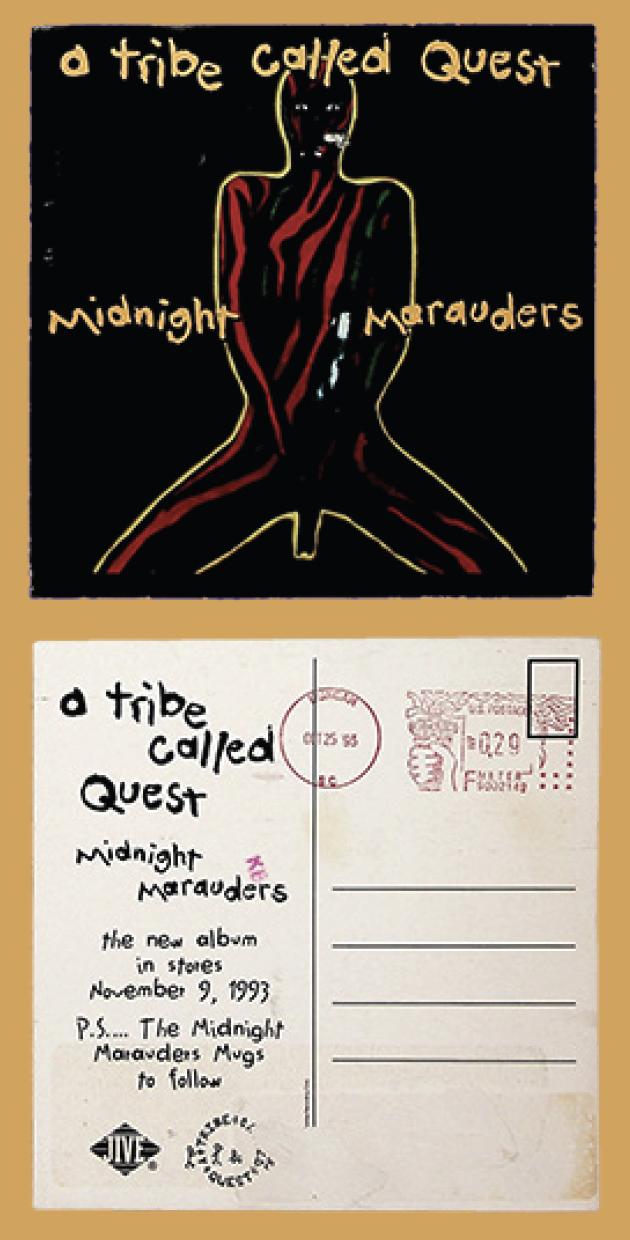

1993

1991

1981

1983

McCormick: When you deal with these early histories, there are obviously lots of conflicting narratives over who did what first, and it can get pretty contentious, with a lot of beefs. How are you going to deal with that as a curator?

Nice: It’s never easy history to sort out. Most of those guys who hung out at the Latin Quarter, who you might think were tough guys, you know, thirty years or forty years later they’re fathers, uncles, grandfathers, just regular guys with lives and families, if they made it. Others, like the Fort Greene Mission Posse, the original 50 Cent, they’re all gone. They got murdered or sent away for a very long time. A lot of the history wasn’t recorded and has been lost. But the flyers do tell you a lot, and people who are still around can read them in ways I can’t. I look at a flyer from the Mitchell Gym on Alexander Avenue in the Bronx, and I wasn’t there. But Easy AD from the Cold Crush Brothers will look at it and go, “Oh Pete, you know that if you went to that Cool DJ AJ show back then, you’d better have gone with four people because if you went alone you were getting robbed. You were losing your sneakers, you were losing your jacket.” There are all these clues on the flyers—where it was, whose party it was—that would tell you how you had to handle yourself, or if you could even go. That’s why it’s cool that the flyers exist. They preserve a narrative.

McCormick: Is that narrative going to be incorporated in the museum along with other fetish objects that people love from hip-hop—so-and-so’s jacket, the microphone from that cat, someone else’s gold records, all the rest?

Nice: It will, and it all makes sense together. Easy AD, who will have his jackets and his suits in the museum, calls the flyers the “Dead Sea Scrolls of Hip-Hop,” which they really are. A dream situation would also be to have the tape of the party playing along with the flyer. We’re just getting started with this, so maybe we’ll get there eventually. You know, things get uncovered every day.

1990

1981

1983

1978

-

Pete Nice was a founding member of the Def Jam Recordings group 3rd Bass and released two gold albums for the label from 1989 to 1992. His career in hip-hop began in 1985 as a solo MC, and in 1987 he established the first hip-hop radio show with DJ Clark Kent at Columbia University, New York. He is currently working with Paradise Gray on the forthcoming book The Golden Age of Hip Hop 1983–1992: An Illustrative History.

Carlo McCormick is a writer, art critic and curator based in New York City. He was a senior editor at Paper magazine for more than thirty years. He has contributed essays to more than one hundred books and his writing has been translated into more than a dozen languages. His next exhibition, a celebration of the fortieth anniversary of the hip-hop movie Wild Style (1983), will opened in November at Deitch Projects in New York.