Books

Containers of Meaning

A conversation about the life and work of photography curator Pierre Apraxine

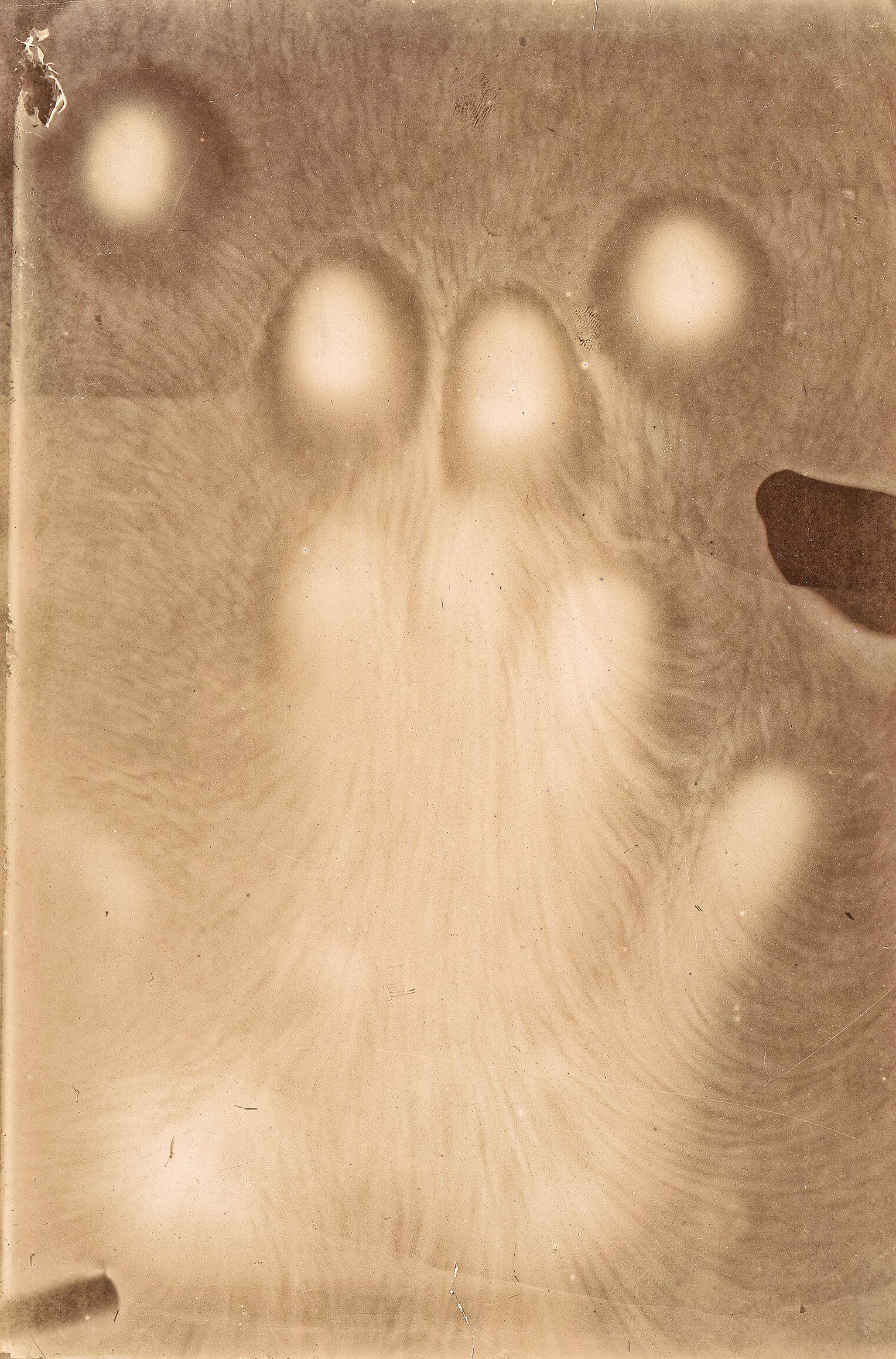

Adrien Majewski, Effluvia from a Hand Resting on a Photographic Plate, 1898–99. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the Gilman Collection © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY.

Pierre Apraxine (1934–2023) was one of the greatest photography collectors and cultural polymaths of his day, the architect of the Gilman Paper Company Collection, which transformed the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s photography holdings when it acquired the collection in 2005. On the occasion of the publication of Apraxine’s autobiography, The Image to Come: Memoirs of a Collector, written with Jean Poderos, Maria Morris Hambourg, founding curator of the Met’s photography department, met recently with acclaimed set and costume designer Chloé Obolensky and French exhibition organizer Olivier Renaud-Clément—all are longtime friends of Apraxine’s—to talk about his legacy and their memories of his place in their lives.

I ask myself, as I write these lines, if it is necessary to continue them. Is it shyness, modesty, or boredom that cause me to doubt whether a project like this is advisable? Is it fear that I will not have the time to finish it that pushes me at once to undertake it and to put off starting it? I’m afraid of oblivion; I’m afraid of not knowing where to start and of not really knowing what to say. I know there is enough material, but I can’t see it. My gaze has so often been directed: look over here, think about this encounter, remember when that happened. But as regards these indications that are at once so specific, so vague, and so frequent in my life, I haven’t had the patience to read them one after the other....

I am a collector, but one doesn’t accumulate objects out of love or out of passion; one accumulates them to play one’s part, to take one’s place in history, without really knowing what either of these things means.

I was born on December 10, 1934, in Estonia into a family that served the tsars. The name Apraxine is not unknown. Its posterity is assured by a character of Tolstoy’s in War and Peace, a Saint Petersburg marketplace, and a number of members of my family who played important roles in the history of imperial Russia. The most famous is Admiral Fyodor Apraxin (1661–1728), who was one of the builders of Peter the Great’s fleet, and one of whose sisters, Marfa, married Tsar Fyodor III. They were followed by a long line of servants of the Empire. On my mother’s side, my grandfather was the last imperial governor of Tver province, and in the early days of the revolution he was assassinated, not for what he was but for what he represented. At the outbreak of World War II, I was five years old. My mother, with her two sons, went into exile in Belgium, where she joined her family. My father followed us there, then returned to Estonia to look after the family business; I never saw him again. He left without me ever knowing what became of him. In Brussels, I discovered a new world and a new language. Above all a new house, so big whereas I was so small. A house that my whole life would not be enough to fill...

—Excerpt from The Image to Come: Memoirs of a Collector (Éditions courtes et longues, 2024) by Pierre Apraxine with Jean Poderos, translated by James Gussen.

Fred Holland Day, Portrait of F. Holland Day with Male Nude, ca. 1987. Platinum print

“He had a kind of faithfulness to his friends, a retentiveness. He was creating his family, furnishing his world with friends that were like family, and it’s the same thing he did with photography. The pictures were not something to own. They were souls that he wanted to cohabitate with.”—Maria Morris Hambourg

ORC: That relationship with Osci and Cornelius existed because one of Pierre’s other great interests was textiles.

MMH: How did Pierre get involved in textiles?

ORC: I can answer that, actually. As Pierre’s relationship with Ocsi and Cornelius developed, he eventually met an important duo, Gail Martin and Vladimir Haustov, who were crucial in opening his eyes to the world of textiles. They founded the important Artweave Textile Gallery with Ocsi at a time when the material was underestimated and overlooked. Another friend (and now executor), Peter Koepke, introduced him to the Indigenous art from the Upper Amazon of Peru of pottery and textiles.

MMH: It’s very characteristic of him. He was constantly curious and functioned in that nebulous region where you don’t exactly know the answer about something, and so he was always looking. That gave him a marvelous, intrepid quality.

ORC: On that subject, curiosity, I think that was my luck with Pierre, because I met him around 1986. The first time I came to America was May 1984. I very quickly started to work with corporate art collections, amazed by the breadth of activity in the U.S. Through that work, I fell upon Pierre’s name, and he was described in some kind of professional publication as, in fact, a collector of textiles. But he was also listed as being connected to the Gilman Paper Company, and I had vaguely heard that company was starting a very impressive photo collection. So out of the blue I called up the company and asked Pierre for a meeting, and since he was so interesting, he received me. I was extremely eccentric and extremely young. I showed up in Pierre’s office in a massive faux-fur coat which was multicolored, with sizzling blue inside lining. The whole office went silent when I crossed it. I had a portfolio of photos that I showed him of the work of Pierre Molinier, the French Surrealist photographer and painter, which Maria knows because this is eventually what I showed to her the first time I met her. Pierre was very amused, very curious, and he bought some photographs on the spot. He asked me when I was coming back again, and that was the start of a long friendship. And he was the one who first connected me with you, Maria. Then I moved to New York, and Pierre was in the habit, when I had a loft in SoHo starting in 1989, to call on me every Saturday with Cornelius Debousie, and we would go looking at antique stores and galleries.

Pierre Apraxine at the Palais-Royal, Paris. Courtesy The Design Library

MMH: I think it’s absolutely typical that Pierre didn’t just receive you and then buy a picture and have a little discussion and that was that. He connected you with his other people. That’s what he did. He had a kind of faithfulness to his friends, a retentiveness. He was creating his family, furnishing his world with friends that were like family, and it’s the same thing he did with photography. The pictures were not something to own. They were souls that he wanted to cohabitate with. He wanted to save them from extinction and to have them around, not necessarily in his own apartment, but as part of a collection.

ORC: And they had to resonate within a larger field, as well, for him. Photographs did not resonate just with other photographs. They needed to resonate with other parts of his life, other things he would have on his mind or think about in the creative world.

MMH: They were little containers of meaning, like a Chekhov story. They were an entire universe unto themselves, where not all the answers were given. So they allowed for meditation, allowed for his curiosity, for multiple associations to come into play. Photographs were a sort of perfect vessel for him to explore.

ORC: When did you and Pierre start talking to each other about the acquisition of photos? How did that happen?

MMH: I think the first photographs he bought were really from the Minimalist and Conceptual collection that was hanging in the lobby on the walls of the Gilman company. And apparently the staff wasn’t quite as urbane as the pictures were, and they said, “We’d all like to look at something a little easier to understand.” Pierre was working at Marlborough Gallery at that point and he went back and pulled out some pictures of Paris, figuring that all Americans wanted to go to Paris or had been to Paris, and that the people in the office would like it. He started with Avedon, and then he added pictures by Brassaï and Kertész, and I think that was the very beginning of Pierre buying photographs. As things happened, in the back room at the Marlborough Gallery, there was a very marvelous, elegant man who was the freelance photographer for the gallery. His name was Paul Katz. Paul was a photographer from early on, age thirteen. By the time he was about nineteen, he was already working as a photographer at the Guggenheim and very involved in the art world. He also had no fear. He had seen a movie about Atget and thought, “Well, his stuff is amazing. I’d love to see more.” Someone told him that Berenice Abbott had all the Atgets, and so he just went to see her and became friends with Bernice. By the same token, he called up Brandt. He called up Robert Frank. Paul was so well-versed in who was around New York, who was a first-rate, artistic photographer, and he talked to Pierre at length over lunches. As Paul liked to say, the Gilman Collection was really born at the Horn & Hardart Automat cafeteria on 57th Street, where they would go and eat a sandwich together. It’s just marvelous to think of the two of them there.

“I remember he would find some new treasure … and he would become very shaky and unsure about it, asking himself: ‘Is Howard going to approve this one? Because yet again, it’s even more expensive than the previous one!’ But he somehow always seemed to succeed and Howard would buy it.”—Olivier Renaud-Clément

ORC: I think it’s important to put all this in context in a way, because we are at a time where photography, as you said, had not really arrived in the art world. Where would I see photographs? Where would I see a book? Where would I see a collection, besides the Museum of Modern Art. It was a time when a lot of treasures were being discovered, unearthed, studied. It was like the box had finally opened.

MMH: I think Pierre had landed on this subject in little increments, a baby step here, a baby step there. But finally, it got into his bloodstream and fascinated him. Howard Gilman was extremely responsive as well. Pierre knew that what was happening in London—where, in 1971, the auction houses had their first photography sales, started by Philippe Garner—brought forth these amazing treasures from attics and basements and dusty cupboards, starting with Great Britain, and also France. And the panoply of 19th-century photography, little by little, came tumbling into these auctions, and it was beyond exciting. Soon there was also kind of renaissance of 20th-century photography that happened in New York, starting in about 1970 and going through at least the middle of the ’80s, if not to the end of ’80s.

ORC: I don’t want to forget to touch on Pierre’s other interests and a bit of his relationship with Howard Gilman. And this brings us back to Chloé, actually. Pierre had a lover, Woody [Heywood McGriff, 1958–1994], who was a great dancer and a member of Bill T. Jones’s company. Pierre was fascinated by dancers and their performance onstage. He was an early follower of Merce Cunningham and Twyla Tharp and Trisha Brown. He knew Trisha very well. And with Howard, they shared that passion. Howard was very involved with the Brooklyn Academy of Music and its impresario Harvey Lichtenstein, which led to the opening of the Howard Gilman Opera House. Sometime in the mid-1980s, this friendship brought about a luminous collaboration between Baryshnikov and Mark Morris, two opposites, which took place on the grounds of Howard’s property in Jacksonville, Florida, where he also had a space for endangered species. Pierre also loved Peter Brook, with whom you’ve worked for so many years, Chloé. He went many times to see The Mahabharata, which was such a major moment in theater of the 20th century.

Adrien Tournachon, Self Portrait, ca. 1855. Salted paper print from glass negative

CO: The Mahabharata was a big adventure for all of us who were involved in it. It was a huge show, and we had to find a way of taking it from our theater, the Bouffes du Nord in Paris, to Zurich on the lake, then to New York at BAM. Without Harvey, we would never have managed. BAM really didn’t have the right space. We needed something more like the Bouffes du Nord, a space free enough for us to improvise things in. I remember it was snowing in New York, and Peter and I walked around that night. We went down a road behind BAM and we were in despair about a space. How could we make it work? As we walked, we saw a building opposite BAM that looked rundown but somehow like the sort of thing that might be possible. We showed it to Harvey, and he said, “It’s the old Majestic Theater. It’s all in pieces.” We asked if he could arrange for us to see it, and they opened it up and we sank through the planks right down to our knees. But we looked around and said, “Provided we can come in and do some things to it, this is the perfect place.” Which is the beginning of the story of how the Majestic was transformed into what is now the BAM Harvey Theater. When all of this was happening, Pierre, because of his curiosity, was right there. He came to see rehearsals. He came with Woody to the production on the third night. And in that time spent with him, I came to understand what he was doing with the collection at Gilman. He really took it upon himself to convince the foundation to go after photography, to forget the Minimalist and Conceptual collections. And he was absolutely right, because this was just at the right time.

MMH: And later on, after Howard had died and the collection still hadn’t come to the Met, Pierre really laid his honor on the line in order to get the collection to be a permanent part of the history at the Met.

ORC: He had found in Howard a real enabler. I remember in the ’90s, when I had no money, and I had left my collaboration with Brent Sikkema at our gallery Wooster Gardens in SoHo. I would help Pierre. He used me as a secretary, and I would take care of the collection and keep it together and make lists, and I spent a lot of time with him. I remember he would find some new treasure from a dealer like Hans Kraus or Harry Lunn and he would become very shaky and unsure about it, asking himself: “Is Howard going to approve this one? Because yet again, it’s even more expensive than the previous one!” But he somehow always seemed to succeed and Howard would buy it.

CO: He always would.

“He kept an unbelievable freshness in his outlook and in his constant interest in things in many different realms, along with a fantastic sense of humor, of course. In Pierre’s world, everything seemed to meet up in the end.”—Chloé Obolensky

MMH: And as we’ve said before, it wasn’t about making this marvelous collection. It was more about the individual pictures. He drew some kind of—I don’t know what to call it exactly—sustenance from the collection. It was as if there were negative spaces in his psyche that were not identified until a picture appeared, and it would give a shape to his feelings, memories, associations. He knew he had to try to articulate these things to Howard, which was never easy, but he managed it over and over and over again. Sometimes we would even buy pictures out of the same album that, let’s say, Henry Lunn had. There were only two good pictures, and he would say, “Which one do you want?” And I would say, “Which one do you want?” And we would settle it amicably because in the end, we knew, or we hoped, that they would end up being side by side again in the Met’s collection. So it was a lovely thing to work with Pierre.

CO: There was such a lightness in Pierre’s spirit, which was a relief, because one can go into something with the seriousness that Pierre had and then it becomes heavy and ornate and ultimately boring in the depth of the specialization. But he kept an unbelievable freshness in his outlook and in his constant interest in things in many different realms, along with a fantastic sense of humor, of course. In Pierre’s world, everything seemed to meet up in the end.

MMH: He somehow retained the joy of childhood.

ORC: The great moment in all of this was really 1993, with the “The Waking Dream: Photography’s First Century” at the Met, the show of the Gilman Collection. It was an unforgettable opening night at the museum. It was that moment when photography, which was still considered an inferior medium, came to occupy one of the greatest museums, in spaces where you would normally see Rubens or Leonardo or any great works from the previous centuries. And suddenly, all of cultural New York is literally—I’m not overstating it—taken by storm with the power of the medium. I remember artists, colleagues, gallerists, people who had nothing to do with 19th-century photographs, going through the exhibition, and then going back again. Artists like Cindy Sherman were completely blown away by what they were seeing and finding there.

MMH: And Pierre had done that. He was a vessel of so much, and he still is. And once again, he’s bringing people together, the three of us here, talking about all of these things and about him.

–

Author, independent curator and consultant Maria Morris Hambourg is the founding curator of the Department of Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. She led the curatorial and conservation team at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for a digital and print publication, Object: Photo; Modern Photographs: The Thomas Walther Collection, 1909–1949 from 2012 to 2014, and co-curated “Irving Penn: Centennial” at the Met from 2015 to 2017. She continues to work with photographers and to write articles on significant figures in the field.

Chloé Obolensky is a renowned designer of sets and costumes for opera, theater and film. Her long-standing collaborations with director Peter Brook include The Mahabharata, The Cherry Orchard and Carmen, among others. In 2011, she won the Abbiati Prize for best costumes for a production of Benjamin Britten’s Death in Venice at La Scala.

Olivier Renaud-Clément has organized exhibitions and acted as an advisor to artists and estates in the U.S., Europe and Japan for many years. He has worked frequently with Hauser & Wirth, collaborating with the gallery on more than thirty exhibitions. He is based in Paris and New York.