Books

The Artist’s Library: Matthew Day Jackson on J.A. Baker’s ‘The Peregrine’

Matthew Day Jackson, Yellowstone Falls (after Bierstadt), 2021 © Matthew Day Jackson. Courtesy the artist, Camille Obering Fine Art, and Guesthouse Jackson Hole

In this installment of ‘The Artist’s Library,’ a recurring series in ‘Ursula’ in which writer and editor Sarah Blakley-Cartwright speaks with artists about a favorite book on their shelves, Matthew Day Jackson discusses J.A. Baker’s ‘The Peregrine’ and what it means to see, fly, and think like a falcon. Published in 1967, the book recounts the author’s fascination with the peregrine falcons that spent their winter near his home in eastern England. Written as a diary covering the months from October 1962 to April 1963, Baker’s lyrical prose borders on obsession as he seeks to watch, track, and ultimately become one with the eponymous falcon.

The Peregrine: 50th Anniversary Edition © 2017 J.A. Baker. Courtesy HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

Sarah Blakley-Cartwright: Thank you for introducing me to this book, Matt. How did you first come across it? Matthew Day Jackson: I’m friends with a cinematographer who did all of the high-altitude filming for this ski company in Wilson, Wyoming, called Teton Gravity Research. He’s really creative, very much an artist, but also deeply technical. He had developed this amazing gimbal that rests on the front of a helicopter—if you look at images from Teton Gravity Research they are all of these really horrifying ski lines that are being filmed, and he is the person filming. One night we met at a bar called the Stagecoach in Wilson, and he was asking me how I do what I do, and I was curious about how he does what he does, and I mentioned that Werner Herzog has a film school. He applied and got in, but he’s a skier—he injured himself and was unable to go. But he got his hands on the reading list, and Werner Herzog considers this book essential reading.

SBC: I saw that. Herzog claims to only see three or four films a year. And he assigns just four texts at the Rogue Film School. That’s Virgil’s ‘Georgics,’ a few pieces of Icelandic poetry, the Warren Commission’s report on Kennedy’s assassination, and this book. How do you think this book might be useful for students of film?

MDJ: Some of the greatest technology in cinema has been about dismembering the camera from the human experience to provide a resource of imagery that isn’t tethered to how we see things. The gimbal on the helicopter is free of any imperfection of human handling. In ‘The Peregrine,’ you see Baker trying to imagine himself flying in the air to reach crazy speeds with beautiful agility.

SBC: And to see like the falcon.

‘Binoculars, and a hawk-like vigilance, reduce the disadvantage of myopic human vision.’

MDJ: If a falcon was human-sized, its eyeball would weigh three pounds. Their eyes are much larger, proportionally, than our eyes. And where they’re placed on their head creates a much wider field of vision. Baker talks about the gray flatness of human sight—but we’re able to see the straight line. We believe in the straight line, which then makes us see the straight line.

‘The peregrine sees and remembers patterns we do not know exist: the neat squares of orchard and woodland, the endlessly varying quadrilateral shapes of fields. He finds his way across the land by a succession of remembered symmetries.’

Matthew Day Jackson, LIFE, 9/20/54, 2012 © Matthew Day Jackson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Matthew Day Jackson, Tower Falls (after Moran), 2021 © Matthew Day Jackson. Courtesy the artist, Camille Obering Fine Art, and Guesthouse Jackson Hole

SBC: You mentioned that this book has become essential to you in the last six months. Was there anything that stuck out to you especially in this reading? Was there anything you’d forgotten that you were surprised to rediscover?

MDJ: The monotony. Did you ever Google Earth where he was trampling around? It’s tiny. He’s hemmed in. Meanwhile, the falcon soars in a space much greater than that of land or surface on earth.

Wherever he goes, this winter, I will follow him. I will share the fear, and the exaltation, and the boredom, of the hunting life. I will follow him till my predatory human shape no longer darkens in terror the shaken kaleidoscope of color that stains the deep fovea of his brilliant eye. My pagan head shall sink into the winter land, and there be purified.

SBC: Baker was possessed by this single-minded focus for a decade, his life’s timetable consumed by the hawks’ departures and arrivals, persevering across fenlands and estuaries through all seasons.

MDJ: And then when he finds it it’s sleeping! In order to read this, you have to resign yourself to it.

SBC: It’s an eccentric text. You have to get into that rhythmic cycle of the pursuit and the encounter. It becomes a powerful ritual.

She drifted idly; remote, inimical. She balanced in the wind, two thousand feet above, while the white cloud passed beyond her and went across the estuary to the south. Slowly her wings curved back. She slipped smoothly through the wind, as though she were moving forward on a wire. This mastery of the roaring wind, this majesty and noble power of flight, made me shout aloud and dance up and down with excitement. Now, I thought, I have seen the best of the peregrine; there will be no need to pursue it farther; I shall never want to search for it again. I was wrong of course. One can never have enough.

MDJ: Did you ever see the movie ‘War Games’ with Matthew Broderick? A computer is hacked and programmed to launch all the nuclear weapons—the computer is just searching for its code. And it’s just a matter of probability.

SBC: It’ll land on it eventually.

MDJ: Eventually it’s going to find it. So it’s just like the numbers, beeeep beep, and then it finds it and goes to the next one, beep beep beep. There are these things that I’m consistently fascinated with and then they just click into place and then form material. \

SBC: Would you say this aspect of the book, the extremity, is relevant to you and your project?

MDJ: I am a mountain person, my love for the snow and my love for the mountains is as deep as the marrow in my bones. I can’t talk about it without getting emotional.

‘Approach him across unfettered ground with steady, unfaltering movement. Let your shape grow in size but do not alter its outline. Never hide yourself unless concealment is complete. Be alone. Shun the furtive oddity of man, cringe from the hostile eyes of farms. Learn to fear. To share fear is the greatest bond of all. The hunter must become the thing he hunts.’

SBC: As the book progresses, Baker recedes as an individual and these divisions dissolve. Even the pronouns collapse at intervals such that he and the bird become inseparable. Suddenly it’s we.

I found myself crouching over the kill, like a mantling hawk. My eyes turned quickly about, alert for the walking heads of men. Unconsciously I was imitating the movements of a hawk, as in some primitive ritual; the hunter becoming the thing he hunts. I looked into the wood. In a lair of shadow the peregrine was crouching, watching me, gripping the neck of a dead branch. We live, in these days in the open, the same ecstatic fearful life. We shun men. We hate their suddenly uplifted arms, the insanity of their flailing gestures, their erratic scissoring gait, their aimless stumbling ways, the tombstone whiteness of their faces.

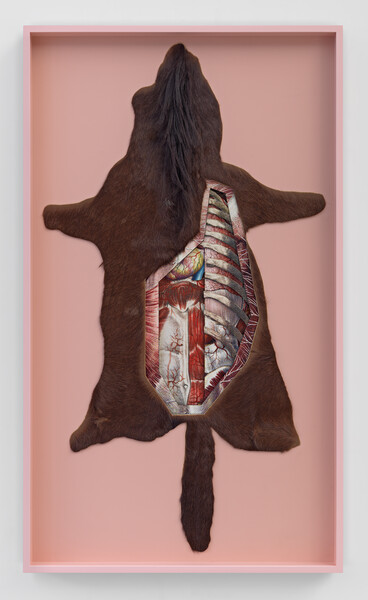

Matthew Day Jackson, Portrait of an Artist, 2015 © Mathew Day Jackson. Courtesy the artist and Grimm Gallery

SBC: He steps out of himself and into the falcon suit. I’m thinking of your ‘Portrait of the Artist’ (2015), in which you’ve tucked, or nested, human anatomy into a wolverine pelt.

MDJ: I placed myself inside a wolverine. We all fantasize about being able to see through someone else’s eyes. Of course, I sound like a little kid imagining myself to be a great beast. But I think of the wolverine as the spirit animal of the artist. The wolverine is solitary but needs other wolverines to make more wolverines. I think of artists in this way, and strangely through the pandemic this analogy seems to hold water. Also, the wolverine punches above its weight class, and I think of artists as some of the most resilient creatures I know. Also, I think wolverines are cute, so there’s that too.

SBC: In the prose, there are inversions: down is up, the skyline is the low hull of the submarine. Looking at things sideways, at a tilt, upside down, it becomes clear that we’re seeing as the falcon sees.

‘The valley sinks into mist, and the yellow orbital ring of the horizon closes over the glaring cornea of the sun. The eastern ridge blooms purple, then fades to inimical black. The earth exhales into the cold dusk. Frost forms in hollows shaded from the afterglow. Owls wake and call. The first stars hover and drift down. Like a roosting hawk, I listen to the silence and gaze into the dark.’

SBC: You fall into this sway of these very vertiginous sentences and almost feel you could tip off the edge of them. It’s an intimate merging, this almost alchemical transmutation of him and this hawk.

MDJ: To describe the peregrine’s observation is a fantasy. I don’t think it’s sexual, but I think it’s somewhere nearing that.

SBC: Everything in this landscape is disappearing. We now know that Baker had been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis while writing this book. The author was disappearing into his illness, as well as into the bird within the text. The hawk is elusive. The birds that the hawk preys upon are enveloped into the hawk. Beneath all this is the knowledge that, in the 1960s, the peregrine as a species was at high risk, without preservation efforts, of disappearing quietly into extinction.

‘Books about birds show pictures of the peregrine, and the text is full of information. Large and isolated in the gleaming whiteness of the page, the hawk stares back at you, bold, statuesque, brightly colored. But when you have shut the book, you will never see that bird again. Compared with the close and static image, the reality will seem dull and disappointing. The living bird will never be so large, so shiny-bright. It will be deep in landscape, and always sinking farther back, always at the point of being lost.’

But finally, after all this merging, Baker is trapped in his own species. He can’t soar like the hawk, he can’t drop at 240 miles an hour.

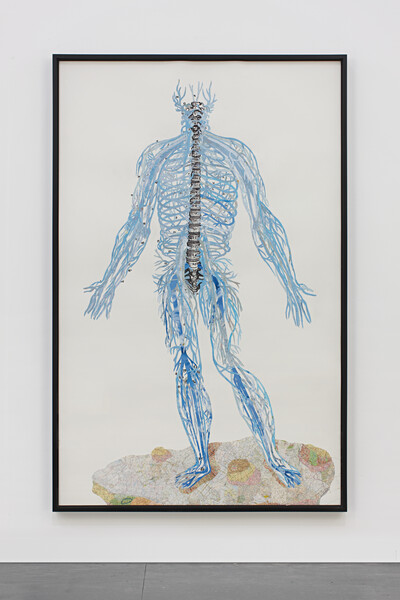

Matthew Day Jackson, Anatomical Drawing (Terra = Muscles), 2011 © Matthew Day Jackson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Matthew Day Jackson, Anatomical Drawing (Seas/Oceans = Nervous System), 2012 © Matthew Day Jackson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

MDJ: At the moment Baker is writing this, he is aware of his physical health.

SBC: His illness is the subterranean topic of the book. It’s not on the page, ever. Which is not to say that death isn’t everywhere in the book.

MDJ: With an autoimmune disease, healthy tissue is being recognized as disease. And there is something about the senselessness of it. To a certain degree, there is a loathing of himself. Of the particular vessel that he’s been put into. This human form that can’t support itself anymore. Rheumatoid arthritis is essentially your body undoing itself. All of its natural tools undo the healthy parts, so that everything is kind of working correctly but in the wrong way.

‘Whatever is destroyed, the act of destruction does not vary much. Beauty is the vapor from the pit of death.’

He was likely in quite a bit of pain while experiencing all of the things that he describes. Leaving his emotions out is a way to salve some of that pain. I have a personal awareness of that to a certain degree. Because I have multiple sclerosis and managed and it actually is the best thing that ever happened to me.

SBC: How did your time spent in Somerset prime you for this book?

MDJ: I rode my bike and I ran. Being able to experience England in this way, the text becomes so much richer. The melancholy in the text is rooted in the soil that has been trampled by feet for thousands of years in exactly the same place. The island has seen overtures of humanity ebbing and flowing, of religions coming and going, of conquerors coming and going. All of those things are recorded in the landscape.

SBC: When you’re out in nature, how do you process what you see? Do you record anything?

MDJ: I don’t. It takes me a while to shed anxiety, and the things that I’m thinking about, and the construction of a life that I’ve made.

‘Everything I describe took place while I was watching it but I do not believe that honest observation is enough. The emotions and behavior of the watcher are also facts and must be truthfully recorded.’

SBC: Baker never does actually record his emotions or his behavior, or insofar as he does it’s only obliquely, through his cataloging of the natural world. We know nothing of the details of his daily life, outside of tracking these hawks. In no way could we call this a memoir even though it is about what he does every day.

MDJ: He doesn’t necessarily describe how he feels but there is a tempo to the writing that you can feel it before the golden tiercel presents itself. There is an exuberance, almost like waiting for a lover at the train or even when I come home and feel the kids are going to be happy to see me. As the book progresses, he starts to know where the hawk is going to be. There is sorrow in the tiercel’s absence. And it’s in the tempo that the exuberance is tangible.

SBC: One particular trait that leaks in is Baker’s troubled conscience surrounding the human impact on the natural world.

‘Near the brook a heron lay in frozen stubble. Its wings were stuck to the ground by frost, and the mandibles of its bill were frozen together. Its eyes were open and living, the rest of it was dead. All was dead but the fear of man. As I approached I could see its whole body craving into flight. But it could not fly. I gave it peace, and saw the agonized sunlight of its eyes slowly heal with cloud. No pain, no death, is more terrible to a wild creature than its fear of man. A red-throated diver, sodden and obscene with oil, able to move only its head, will push itself out from the sea-wall with its bill if you reach down to it as it floats like a log in the tide. A poisoned crow, gaping and helplessly floundering in the grass, bright yellow foam bubbling from its throat, will dash itself up again and again on to the descending wall of air, if you try to catch it. A rabbit, inflated and foul with myxomatosis, just a twitching pulse beating in a bladder of bones and fur, will feel the vibration of your footstep and will look for you with bulging, sightless eyes. Then it will drag itself away into a bush, trembling with fear. We are the killers. We stink of death. We carry it with us. It sticks to us like frost. We cannot tear it away.’

MDJ: To be critical without pointing the focus of that criticism onto oneself is to deny the simple fact that oftentimes the things we loathe we embody. Baker sees himself in the booming guns surrounding him on certain days, the clumsiness and the stupidity, the smokestacks.

‘I have always longed to be part of the outward life, to be out there at the edge of things, to let the human taint wash away in emptiness and silence as the fox sloughs his smell into the cold unworldliness of water; to return to town a stranger. Wandering flushes a glory that fades with arrival.’

Matthew Day Jackson, Bouquet with Lead Flowers in Leaden Swap, 2021 © Matthew Day Jackson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Matthew Day Jackson, Ghost Bouquet V, 2020 © Matthew Day Jackson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

SBC: You often work with poured lead and bronze, industrial materials with perilous properties. Why, as someone who loves nature, use poisons and toxins, materials that oppose and corrupt nature?

MDJ: For me, either it’s my likeness or the size of my body or using materials in a sort of haphazard manner which are fundamentally poisonous is a commentary both on my individual self, my white maleness, and of the form that I inhabit en masse alongside all human beings.

‘No pain, no death, is more terrible to a wild creature than its fear of man. A red-throated diver, sodden and obscene with oil, able to move only its head, will push itself out from the sea-wall with its bill if you reach down to it as it floats like a log in the tide. A poisoned crow, gaping and helplessly floundering in the grass, bright yellow foam bubbling from its throat, will dash itself up again and again on to the descending wall of air, if you try to catch it. A rabbit, inflated and foul with myxomatosis, just a twitching pulse beating in a bladder of bones and fur, will feel the vibration of your footstep and will look for you with bulging, sightless eyes. Then it will drag itself away into a bush, trembling with fear. We are the killers. We stink of death. We carry it with us. It sticks to us like frost. We cannot tear it away.’

MDJ: Even in the sight of a human being, an animal can wrestle itself up to its sickened limbs to run off because the fear of man is more fearful, more terrifying than death itself. There is this unwashable stink that we can never shed, that all of nature, all of our natural environment smells on us. Something deep in our human animal, ancient, can smell that reeking wave of stink emanating from our bodies.

‘The only movement was the silent threshing of the hawk’s long wings beating through the sunlit aisles. Silent to me; but to mice in the short grass, to partridges hidden and dumb in long grass under the trees, his wings would rasp through the air with the burning whine of a circular saw. Silence they dread; when the roaring stops above them, they wait for the crash. Just as we, in the war, learnt to dread the sudden silence of the flying bomb, knowing that death was falling, but not where, or on what.’

SBC: How does an artist gracefully slip in this sort of medicine so it doesn’t seem didactic?

MDJ: Art’s job is not to simplify things. Even to empty something of its content, or to try to empty something of its content, is not to reduce the possibilities of how it could be understood. In this book, calmness means the peregrine isn’t there. But Baker likens quiet also to the silence when he was a child during World War II. There’s only one snippet where he says that the silence was actually kind of scarier because that felt like apprehension.

SBC: Threat is everywhere in the book, the menace of impending annihilation.

Matthew Day Jackson, Man’s Best Friend, 2014 © Matthew Day Jackson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Matthew Day Jackson, A Brief History of the Domestication of Animals, 2014 © Matthew Day Jackson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

MDJ: This book is apocalyptic. But the birds and the deer and the vole and the sea otter and the jellyfish won’t recognize that we are gone, nor that we were even there in the first place.

‘A magpie chattered in an elm near the river, watching the sky. Blackbirds scolded; the magpie dived into a bush as the tiercel peregrine flew over. Suddenly the dim day flared. He flashed across clouds like a transient beam of sunlight. Then grayness faded in behind, and he was gone. All morning, birds were huddled together in fear of the hawk, but I could not find him again. If I too were afraid I am sure I should see him more often. Fear releases power. Man might be more tolerable, less fractious and smug, if he had more to fear. I do not mean fear of the intangible, the suffocation of the introvert, but physical fear, cold sweating fear for one's life, fear of the unseen menacing beast, imminent, bristly, tusked and terrible, ravening for one's own hot saline blood.’

SBC: There’s a sentimental way of thinking about nature as peaceful and introspective, but this book stages wild life, the bacchanalian carnage of the hunt: both Baker’s conquest of the hawk and the hawk’s own conquests which Baker witnesses. Your work often depicts predators.

MDJ: I inhabit a form that is totally enabled by a culture of death-making with a rapacious regard to people and the environment. The work has always been a reconciliation of me, as a person, seeing the darkness in my own self mirrored by the systems of support and structure which support my existence. The fences and the holes we dig and the blights that we plop on, the pond that we poison, all of these are reflections of who we are. These traces are a record of our humanity. The United States is an incredibly violent culture and the thing that makes it sinister is the forms in which we articulate it from the personal to mass, from macro to micro. How does an individual negotiate that relationship with a network of extraordinarily ugly things that is fundamental to a lot of our existence?

SBC: In talking about your work, we must talk about violence and savagery. But I also see your work folding in optimism and the promise of beauty, these cycles of coexistence.

MDJ: The record of the thing, the thing that’s left behind, a text, a painting, or whatever the fruit is of whatever we labor over, I feel fundamentally has to affirm some goodness or else then the point of living at all doesn’t really make sense. Does that sound romantic or stupid?

SBC: No, it doesn’t.

MDJ: I appreciate you asking me to do this.

SBC: Thank you so much, Matt.

–

Matthew Day Jackson is an American artist whose multifaceted practice encompasses sculpture, painting, collage, photography, drawing, video, performance and installation. His art grapples with big ideas such as the evolution of human thought, the fatal attraction of the frontier and the faith that man places in technological advancement.

Sarah Blakley-Cartwright is a New York Times bestselling author. She is Publishing Director of the ‘Chicago Review of Books’ and Associate Editor of ‘A Public Space.’

Excerpts from ‘The Peregrine’ by J.A. Baker © 1967 J.A. Baker. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. Recent editions are available from New York Review Books Classics and HarperCollins Publishers.