Conversations

Shit Talking

Artists, collectors and curators weigh in on Manzoni’s tins

In the 60 years since its creation, Piero Manzoni’s ‘Merda d’artista’ has inspired a vast range of reactions, from the shock and scandal it initially provoked to the revered—if roguish—place it holds in the canon of modern art today. On the occasion of this anniversary, Ursula has invited a group of artists, curators and collectors to discuss the importance of the work—personally and art historically, from the scatological to the ontological—shooting the shit, so to speak, about Manzoni and his radical approach to art-marking.

Walter Baldi, Collector

I can’t think of another work in the history of art that has provoked so much wide-ranging debate, starting with the parliamentary motions that were made when it was first exhibited in Rome, up until today. The fact that we are still here talking about it 60 years later is, in my opinion, an extraordinary thing. I’m biased because I own one, but I think it’s one of the most important works in the history of art and an icon of the 20th century. Perhaps the most trivial question, the one we’ve all asked ourselves, is ‘What’s inside this little box?’ It amuses me because today there is still no answer.

The people who were there at that time and witnessed ‘Merda d’artista’ tell stories that are at odds with each other. In my opinion there will never be an answer to what’s inside the box, and something more important is happening, this little box of shit is growing in value. I did a calculation today and its value is no longer the equivalent of 30 grams of gold, as when Manzoni first produced the work, it now costs 10,000 grams of gold, that is 10 kilos of gold. It is likely that soon its value will go from 30 grams to 30 kilograms of gold. I think this idea would even shock its creator, the little genius.

Ebecho Muslimova, Artist

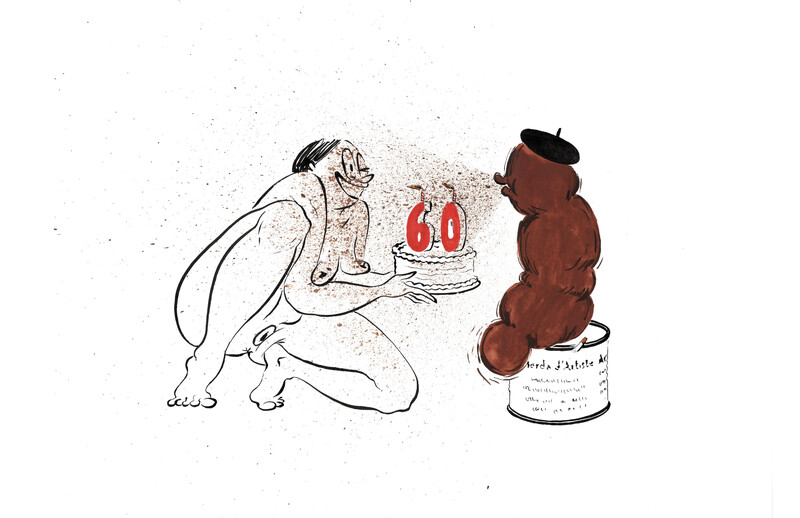

Responding to the 60th anniversary of ‘Merde d’artista,’ Ebecho Muslimova created a brand-new work—in essence, a birthday present—featuring Fatebe, the raucous and sexually uninhibited character who frequents the artist’s paintings and works on paper.

© Ebecho Muslimova

Judith Bernstein, Artist

‘Artist’s Shit’ expanded the definition of art. It’s extraordinary in terms of the timeframe Manzoni made it. It forces the viewer to think and see differently. And that is what revolutionary art is about. His work defied convention and expanded on the idea of Marcel Duchamp’s urinal. He makes the leap from urine to shit. He poses the idea that everything about the art and the artist can be art, down to their bodily functions. The artists and everything they produce falls into the category of fine art, something worth its weight in gold. It broadens the possibility for all artists to think about themselves and their work in the same way. The artwork was first shown in Milan in 1961. But I learned about it when I moved to New York in ’67, after going to graduate school at Yale. I saw the work in person at a later date.

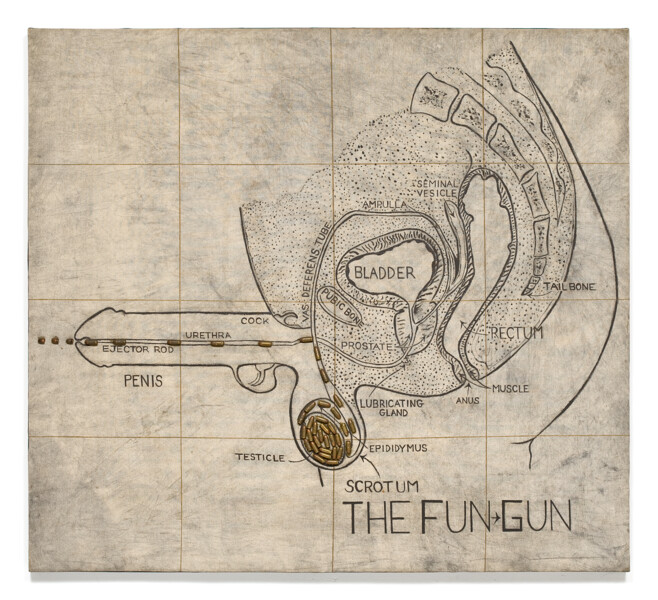

My work has always been about the connection between the political and sexual. And while I was at Yale in 1966, I read an article in the New York Times that said the title ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’ was taken from bathroom graffiti. At that time, Yale was an all-male undergraduate school. I went into the men’s bathrooms and took inspiration from the scatological graffiti I found there. That’s my idea of feminism, critiquing male behavior. And later on, I started critiquing female behavior, because I’m dealing with the whole human condition. Like Manzoni, I use bodily functions, body parts and crudity to convey my message. The contents and issues are different, but there’s a similar courage it takes to address issues that haven’t been addressed before, especially by a woman. I use imagery of semen to illustrate getting fucked. In my work, crudity is delivered in a humorous way, which makes the message more palatable and accessible to the viewer. Humor and laughter is very much like an ejaculation—a release—but it doesn’t discount the seriousness of what I’m trying to say.

Judith Bernstein, Fun Gun, 1967 © Judith Bernstein

Carlos Basualdo, Curator

There’s a tongue-in-cheek quality to the work, a lighthearted attitude, which makes it look much more innocent than it truly is. After you are able work through this atmosphere of play, which is such an important part of Manzoni’s work, you get to the core of really serious questions about the ontological status of an artwork, the position of the artist as a subject in a system that tends towards the complete eradication of any signs of subjectivity to subsume absolutely everything in the market sphere. It’s interesting to think about ‘Merda d’artista’ in the context of Manzoni’s earlier work and also in the context of pop art, which is more or less contemporaneous with Manzoni. Some of these ideas and questions explode a few years later, but there’s definitely an interesting relationship with Andy Warhol and his own reaction to the market.

Although ‘Merda d’artista’ precedes the Campbell’s soup cans by a year, Warhol is making a similar statement about the relationship between commodities and art. One needs to consider the work that Manzoni was doing before with the ‘Lines’—the first presentation in 1959 was almost like a shop. Manzoni’s presentation of the ‘Lines’ as commodities was very intentional and is an interesting response to the readymades. The Schwarz editions of the readymades [the Milanese art dealer Arturo Schwarz produced editioned replicas of 14 works by Marcel Duchamp] were produced in 1964, so Manzoni’s ‘Lines’ and ‘Artist’s Shit’ precede the Schwarz edition by several years. Piero Manzoni’s ‘Merda d’artista’ is a very prescient response to the readymade that anticipates and is in dialogue with the Schwarz edition and certainly with early pop art.

Manzoni produced 90 cans of ‘Merda d‘artista,’ each containing what was said to be 30 grams of the artist’s own excrement, which Manzoni proposed be valued at the same price as the equivalent weight in gold © Fondazione Piero Manzoni, Milan

Stefan Brüggemann, Artist

‘Merda d’artista’ is a masterpiece in the sense that it’s a simple idea with a lot of meanings. You can read it in so many ways and on so many levels—a political comment, a financial comment, a consumerism comment, an existential comment. It’s the kind of conceptual work that doesn’t need explanation. He’s playing with this idea that the role of an artist is to express things from the inside to the outside. It’s a production, it’s a sculpture, packaged and ready for the viewer to consume now. It’s very difficult to get inside the head of Manzoni, but as I see it in my connection to my work, it’s this idea of questioning the bullshit of language.

The aura we sometimes generate around an artwork, and overthinking a work of art can also leave you in a space that is full of shit. As the New York philosopher Harry Frankfurt wrote in his essay ‘On Bullshit,’ it’s this idea that one can no longer separate truth or lies. We have to call ‘bullshit.’ It’s about an excess of language. Connecting this to ‘Artist’s Shit,’ I think Manzoni poses a similar question to the art world. You really don’t need to think too much about the work. It is what it is, in that sense. This provocation is what I like about the work. It’s everything and nothing at the same time.

Stefan Brüggemann, FREE (UNTITLED ACTION), 2020 © Stefan Brüggemann

Piero Manzoni with cans © Fondazione Piero Manzoni, Milan

Vesela Stretenovic, Curator

The first time I encountered ‘Merda d’artista’ was in my early college years in Belgrade, former Yugoslavia. I had an amazing professor of modern and contemporary art who taught us wonderful things and exposed us to a lot of interesting art, including Manzoni. At home in my parents’ apartment there was a book by Alberto Moravia called ‘The Conformist.’ Somehow, for me, ‘Merda d’artista’ connected to the novel as its visual anecdote, a nonconformist, nonsensical work of art. It exaggerates to undermine the norms, disguises itself as foolish entertainment, only to question everything. It devalues the noble status of art. It acts as an agent against the establishment.

It is an act of artistic provocation. Later on while studying at grad school, I wrote a paper on Manzoni, but it was not about the ‘Merda d’artista,’ it was about his ‘Achromes.’ These are totally different works to ‘Artist’s Shit,’ but also spoke to me visually and poetically, and my interest continues to this day. It’s very interesting as someone from Europe, living in United States now for most of my life, how certain artists or artworks have different recognition or resonate differently between the two continents. Manzoni’s work is still not as well-known in the United States or appreciated in the way that it should be.

Walter Baldi is a collector based in Milan, Italy.

Carlos Basualdo is Senior Curator of Contemporary Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and is on the advisory board for the new edition of the Manzoni Catalogue Raisonné. Judith Bernstein is an artist currently living and working in New York NY.

Stefan Brüggemann is an artist currently living and working between London and Mexico.

Ebecho Muslimova is an artist currently living and working in New York NY.

Vesela Stretenovic is Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.