Books

Book Table: Pacific & Cassandra Press

‘Ursula’ catches up with two small presses ahead of Printed Matter’s Virtual Art Book Fair

Books hat, Pacific. Photo: Dan Bradica. Courtesy Pacific

Twice a year—April in Los Angeles and September in New York—artists, publishers, zine-makers, and antiquarians gather for Printed Matter’s Art Book Fair. Hosted by the venerable New York bookstore and publisher, the fair unites thousands of attendees in a passion for books, from rare editions under glass to inexpensive zines spread seemingly by the acre on tables. Publications, however, constitute only one part of what's exchanged and what has made the fairs a grassroots cultural phenomenon over the last decade; their international draw of the most compelling voices in contemporary art publishing sets the stage for days of planned and impromptu conversations about new ideas, practices, and books yet to be published.

This year, Printed Matter has consolidated the September 2020 and April 2021 editions of the fair into the first Virtual Art Book Fair, opening February 24 and running February 25–28, inviting more than 400 exhibitors to present their wares through an individual website, in lieu of gatherings. Ahead of the fair, 'Ursula' magazine caught up with two innovative small presses, in hopes of trying to recapture at least some of the flavor of the conversations with exhibitors and friends that typically permeate the fair booths and tables. Pacific is a New York–based publisher founded by Elizabeth Karp-Evans and Adam Turnbull, whose books, catalogues, facsimiles, zines, and editions seek to give a platform to a variety of viewpoints and push the boundaries of how publications function in the world. Cassandra Press is a Los Angeles–based publishing and educational platform founded by artist Kandis Williams; its comprehensive reader editions and community programming champion the dissemination of Black scholarship.

Elizabeth Karp-Evans, co-founder of Pacific. Photo: Ned Rodgers. Courtesy Pacific

‘Garvey!: Issue 1,’ by Alvaro Barrington, Pacific and Sadie Coles HQ, 2019. Photo: Dan Bradica. Courtesy Pacific

Pacific Tell us about Pacific. How was it started? What are your goals as a publisher?

Elizabeth Karp-Evans: Pacific was started in 2016 by Adam Turnbull and myself. We both had been involved in making publications for nearly a decade—designing, editing, physically making books—but we’d never published anything. When you do something creative long enough, the desire is to make what you want to see in the world. That’s not always easy, I believe you have a responsibility to yourself and your audience to create something of value, and there is a power dynamic within publishing as far as resources are concerned. So when we started Pacific it was about showing ourselves and our community that we did have the power to do something that people who didn’t look like us were doing, and to create something of value for our friends. That was five years ago. We now run the publishing imprint as well as a creative studio called Studio Pacific. One important goal that has remained the same is that we always strive to free the book as an object. So many of the books that we were making before launching Pacific were an accessory to something larger, usually an exhibition, but the context within which many people experience a publication is outside of the environment which it was made. We always try to think of the lifespan of a book. We’re making something that will, hopefully, last a long time, a lifetime, and there’s a certain amount of care and consideration that should go into it. We also strive to amplify the voices of our community. Despite our growth, there were people who supported us from the beginning who we’ll always be grateful to and always want to make books with.

‘Books have the power to change society. Publishing can be a really radical practice, both online and in print, because of the accessibility of the product and because most people can make a mark and understand a mark.’—Elizabeth Karp-Evans

Why books? What aspects of printed matter as a medium enable your publications to work the way you want them to out in the world?

EKE: Books have the power to change society. Publishing can be a really radical practice, both online and in print, because of the accessibility of the product and because most people can make a mark and understand a mark. We view publishing as a vessel, we’re the bridge between the artist or writer and the format of a book. Their ideas and voice pass through our studio and manifest as printed matter. We enjoy publishing because it’s a very authentic process and a very collaborative process, we believe deeply in the titles we work on and we try to make the process as accessible as possible so that at the end of a project, there is a mutual understanding of how a book was actually made.

‘Democractic Intuition’ by Meleko Mokgosi, Pacific, 2020. Photo: Dan Bradica. Courtesy Pacific

Spread from ‘Democractic Intuition’ by Meleko Mokgosi, Pacific, 2020. Photo: Dan Bradica. Courtesy Pacific

What sort of reader experience do you want to facilitate?

EKE: We really work to make each book feel unique because we want readers to consume thoughtfully and to understand the labor that most books contain. We just published a title with the artist Meleko Mokgosi and Jack Shainman gallery that documents the series, ‘Democratic Intuition,’ that he’s been working on since 2013. And due to the pandemic, it took nearly a year to make. So when people are viewing books, oftentimes they are looking at years of a person’s work, sometimes decades! From my experience, there are fewer opportunities for women and BIPOC artists to make publications, we end up working harder. As an artist and a publisher, I want to make sure that when people pick up one of our publications, they hold on to it and spend time with it, because that much more effort on the author's behalf went into it existing in the world.

What is an ideal project for you? What sort of qualities are you looking for in an artist’s practice or a project’s scope that makes its content something you want to champion? Any recent titles that exemplify this?

EKE: Every project is different, but ideally we’re involved in a project from beginning to end, in that we get to ideate and work closely with an artist or client all the way through to printing and distribution. We love working with artists, but have also had amazing experiences working with other publishers, museums and galleries. Recently, we worked with Verso Books to design the cover of ‘Glitch Feminism’ by Legacy Russell and it was a fantastic experience. We’re also working on launching a writing series in 2021 that features female-identifying voices**,** so there really is no single type of ideal collaborator on a project. We like to spend time with artists to understand their practice and their ambitions for a book or a project, and with that, we hope to build that trust that allows for us to put forward ideas, too. We like to balance out the needs for a project with the needs for us as a publisher and studio to run with our creative process. It’s a balance that we enjoy. We do love working with artists who have never made a book before, especially those working for a long time. Often, these are the individuals who have really amazing ideas about what a book can be because they have no prior example of how a publication should be structured.

‘Glitch Feminism’ by Legacy Russell, Verso Books, 2020. Cover design by Pacific. Photo: Dan Bradica. Courtesy Pacific

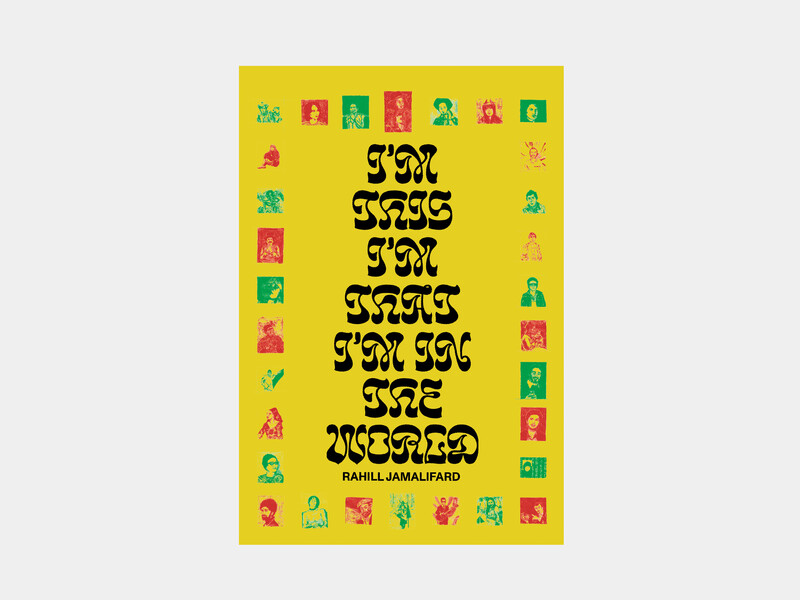

‘I’m This, I’m That, I’m in the World,’ by Rahil Jamalifard, Pacific, 2021. Photo: Dan Bradica. Courtesy Pacific

We also like using publications as a medium for someone’s creativity and talent, that isn’t something they’re necessarily recognized for in the world. We’re launching a book this quarter titled ‘I’m This, I’m That, I’m in the World’ with the singer Rahill Jamalifard of Habibi, who happens to draw these amazing portraits of other musicians, past and present, that have only been available to view online.

As both a publisher and creative studio, what’s your typical structure for projects and the genesis of your collaborations?

EKE: We have a creative process that we apply to everything we do in the studio, whether it is a book, website, poster, brand or identity system. We do a lot of research and then strategize and devise a plan to design, produce, and launch a project. No matter what the budget is, the intention of creating is to make something that people respond to, that they like or need, and that is accessible. Most projects happen very organically and start with a conversation, whether it’s us reaching out to someone or vice versa.

How has the past year—the pandemic, vast social and political upheaval, and other tumult—shaped your thoughts on the role of books in our lives? As a publisher, how has Pacific responded to the past year?

EKE: The past year has underscored the importance and value of community, and how you take care of each other. As a publisher, part of our mission is that ‘we recognize there are a multitude of stores to tell, and to hear…’ The work has always been about an exchange. A lot of the publishing and arts community were in crisis—especially individuals, small presses and small businesses, and we really tried to listen and to help. We have worked with artists and institutions to move their presence online in order to interact, exchange, and gather safely, and are now really thinking about the future of publishing in a digital space—there are so many new opportunities and experiences to access community digitally, specifically for Black and brown communities. Many of the projects we’re working on at the moment are both a printed book and an online experience, and we’re excited to continue this practice. As far as books playing a role in our lives, we’ve seen the same demand in the last six months as pre-pandemic. Printed matter will always be significant, how it remains utilitarian is exciting to think about.

‘The in-person experience, especially in New York, is so exhilarating and it will return, but we do see this as an important space for the community to interact and engage with audiences globally in new more inclusive ways, which is super exciting.’—Elizabeth Karp-Evans

Printed Matter’s Virtual Art Book Fair is this month. What are you most excited to present there? This is the first year the fair is completely online; how did Pacific adapt to this format? Does this feel like the future of these sorts of events, or do you think that in-person interaction with books, artists, and publishers is irreplaceable?

EKE: We wanted to approach the format with the same ethos as above, and transition to the digital instead of trying to translate the physical. Instead of one specific project, we're excited to present our ‘booth’ as a space. We hacked the site a bit to add video, an interactive element, and music by our friend Time Wharp, who’s amazing. We don’t think this is the future of the fair. The in-person experience, especially in New York, is so exhilarating and it will return, but we do see this as an important space for the community to interact and engage with audiences globally and in new more inclusive ways, which is super exciting.

The new design of Afterall journal by Pacific. Courtesy Pacific

What’s next for Pacific?

EKE: As a studio we’ve begun to take a very holistic approach when working with clients and collaborators. We’ve seen a huge increase in digital projects, while the demand for print is still very strong. Afterall, a Research Centre of University of the Arts London, located at Central Saint Martins, is an example of this. We just redesigned their storied journal and reimagined the design of their ‘Two Works’ series—featuring upcoming titles with Estefanía Peñafiel Loaiza, Tschabalala Self, and Julie Mehretu—while also creating a digital space for live programs, educational resources, and an important forum for scholars and critics called Afterall Art School. On the publishing side, Rahill’s book and Mason Saltarrelli’s ‘Eternally Rowing’ are launching this quarter, and we’re also working on a book with Toyin Ojih Odutola and Jack Shainman gallery that really encapsulates the spirit of ‘book as object’. The first book in the writing series we’re aiming for a fall 2021 release. And there’s always a few projects that are too early along to mention, but stay tuned!

Cassandra Press Tell us about Cassandra Press.

Kandis Williams: Cassandra Press is changing pretty drastically right now. We’re shifting from a focus on acquiring and figuring out new ways of disseminating content—what we’ve been calling ‘messy dissemination practices’—and focusing now on producing original content with a small network of Black creators and scholars that we’re really happy to be in dialogue with. We started Cassandra Classrooms this year, and we’re launching four more in March. This time we’re doing a really interesting approach to the classrooms and thinking about them as public editions.

You are working in all of these different platforms and formats. How do you think across these mediums?

KW: The thing that connects all of this is a commitment to Black scholarship and to reading in between the lines of how we’ve been produced culturally, how we’ve been produced racially, how we’re constantly produced and reproduced socially. We’re interested in the congruities and incongruities in certain Black thinkers and different diasporic pools of thought, and how so many artists historically and in the contemporary work through access to and exclusion from various means of production. Thinking across platforms and across formats has been a really collaborative process.

Kandis Williams, founder of Cassandra Press, 2017. Photo: Dicko Chan. Courtesy Cassandra Press

READER ON PLANTS movement, metaphor and migration,’ Cassandra Press, 2021. Courtesy Cassandra Press

As you’re moving from this ‘messy dissemination’ to original content, what are the commonalities among the viewpoints you want to champion?

KW: It’s simply thinking about Black scholarship as a thing that’s been happening in between a lot of libidinal economies, a lot of political economies—this affective political strength of Black collective and civic movements. Also thinking about how the individual deals with and negotiates being structurally embedded and being an individual character—this is W.E.B. Du Bois’ stuff—and how culture is produced from that tension, especially around Black bodies. That’s been something that all of our courses hold, and it’s something that my readers have really dug into and expounded on. We’re trying to understand and reduce and deduce what the monolith of ‘Black’ is. I’m excited for a new project with Hamza Walker where we’re going think through a series of publications on what the ‘Black image’ even is. It sounds straightforward, but what we’re realizing as well is that there’s so much rich and creative force that’s undermined and undergrounded and underrepresented. We’re thinking about how to bring those forms to the fore in a moment where I think there’s also very much a cultural request for such material and praxis and ways of thinking.

‘Something that keeps invigorating me is the absolute necessity for our cultural artifacts, our cultural property, our cultural history to be more widely disseminated’—Kandis Williams

How has Cassandra Press adapted to the tumult of the past year?

KW: We’re adapting as most Black bodies do—daily. Really charging ahead with the ways of communicating and producing that we want to be invested in. Something that keeps invigorating me is the absolute necessity for our cultural artifacts, our cultural property, our cultural history to be more widely disseminated and to not be so mediated by institutions without ethical frameworks, or even just the relative knowledge of our subject matters and our subjectivities and our subjectivization.

What are you most excited to present at the fair?

KW: I’m excited for all of the new publications. There’s a reader on plant migration and movement and the metaphors around plants structures that I’m super excited about, it’s been about a year of research for me.

What’s your process like developing those readers? They’re incredible resources.

KW: It’s very persistent research. A lot of reading, rereading, storyboarding. There’s no one particular process, it really depends on the content and material. Working with archives and libraries has been super exciting. Every archive we’ve worked with, I realize how much more important this work is because archives are so dense and convoluted to get through. And seeing our teachers starting to make readers for their courses has been super exciting. These are all different means of connecting—it feels like a pedagogical relationship that is very personal and doesn’t necessarily have any protocol.

What are your thoughts on the fair’s digital format this year and how this affects the communal experience of the fair?

KW: I miss the fairs—seeing other vendors and friends—but what I don’t miss is what I don’t miss about a lot of pre-pandemic social organizations, which is that the fair was very white. That’s been difficult in a lot of ways, the feeling that the Black audience that we have been able to deeply connect to online was priced out or didn’t have access to or didn’t feel welcomed in so much of the fair context. That’s been a discussion with Printed Matter as an organization, and with a lot of organizations, especially art spaces. There are all sorts of issues of fetishism, of renegotiations of content, of whitewashing, that I can manage dealing with a lot more intentionally because of the fair’s lack of physical space. That’s been a relief in many ways. And I think we’ve also been able to align our community more directly with the text. Something that I always feel is missing in the fairs is the time spent actually reading together or digesting different texts together. It’s been really lovely to have a more discrete community to do that with versus just in-passing in a huge crowd. So the intimacy there has been really productive for us.

‘Something that I always feel is missing in the fairs is the time spent actually reading together or digesting different texts together. It’s been really lovely to have a more discrete community to do that with versus just in-passing in a huge crowd.’—Kandis Williams

What’s next for Cassandra Press?

KW: In the coming year, we’re doing a couple of institutional shows: a show at Luma Westbau and a Sanford Biggers show at the California African American Museum with Amistad Research Center, Rivers Institute, and Sanford Biggers Archive. We just wrapped a project with William Pope.L called ‘End Notes’ that was really interesting—kind of an algorithmic approach to understanding Black praxis in its various components and applications. We have a Classroom discussion that I had with Derrais Carter and Anya Wallace, who are going to be teaching our ‘Black Err/or’ class. We’re also thinking about launching an upcoming sculpture edition that will be essentially sculptures gathered around a text to produce a singular sculpture. We’re excited to expand in that way. –

Elizabeth Karp-Evans explores a multidisciplinary practice of writing, editing, design, and artmaking. Her work addresses questions of personal history, built environments, and memory. She holds an MFA from the New School for Social Research and is a former interviews editor for ‘Guernica.’ Her work has been shown at SIGNAL gallery, Shoot the Lobster, Gordon Robichaux, and Jack Hanely gallery. She is a 2018 artist-in-residence at the Rauschenberg Residency in Captiva, Florida. Her debut poetry collection is titled ‘Proper Ground.’ Elizabeth is co-founder of Pacific.

Kandis Williams is a visual artist whose practice spans collage, performance, writing, publishing, and curating, and explores and deconstructs critical theory around race, nationalism, authority, and eroticism. Her work focuses on the body as a site of experience, which is simultaneously co-opted as symbol. Williams is the founder and editor-at-large of Cassandra Press, an artist-run publishing and educational platform producing lo-fi printed matter, classrooms, projects, artist books, and exhibitions. The platform’s intention is to spread ideas, distribute new language, propagate dialogue-centering ethics, aesthetics, femme-driven activism, and black scholarship because y’all ain’t listening.

For more information, visit the Printed Matter Virtual Art Book Fair. When the fair opens on 24 February, be sure to visit Pacific and Cassandra Press, as well as Hauser & Wirth Publishers, who will be featuring new titles on Luchita Hurtado, Rita Ackermann, Richard Jackson, Rashid Johnson, and Lucio Fontana.