Conversations

Phyllida Barlow: the edges of things

Jennifer Higgie talks to the artist about Giacometti, lockdown and the theater of sculpture

Phyllida Barlow in her London studio. Photo: Cat Garcia

‘London has become a stage,’ Phyllida Barlow wrote in 2020, ‘buildings are watchful, the street lighting dramatic, their gleam spilling onto the banalities of pavement and roads; there is an atmosphere of suspended animation—nothing moves under this deathly curfew.’ It is this visceral and visual language of the city that has been a source of inspiration for the British artist for more than 50 years.

Working from her home studio ahead of exhibitions in Zurich and Munich, Barlow found this time productive, a return to the simplicity of making, revisiting old works, and imagining a set design for Mozart’s ‘Idomeneo.’ Her creative energy is in some way at odds with her immediate surroundings, as she tells Jennifer Higgie, editor-at-large of ‘frieze’ magazine and host of Bow Down podcast, via Zoom, ‘half the road near to where we live here, it’s all boarded up.’

Jennifer Higgie: Maybe we could start off with ‘small worlds’ which is the title that you’ve given your show in Zurich. Could you tell us a bit about how this show came about and how being in lockdown for the past year or so in London has influenced your working processes?

Phyllida Barlow: In terms of making work, I think as the weeks went by, I realized simplicity, straightforwardness, kind of the minimum of ambition, the minimum of ideas, the minimum of seeking innovation, I just wanted to get rid of all that. I wanted to be as close to the work as I possibly could with the simplest of materials that I was the most used to, that in a way present themselves also as very real challenges in how they can be used, manipulated, et cetera. So the footprint of experience that I wanted to resource was very small but offered endless possibilities.

Phyllida Barlow, untitled: memorialplace; 2020 lockdown 5d, 2020 © Phyllida Barlow

Phyllida Barlow, untitled: fragiletower; 2020 lockdown 8, 2020 © Phyllida Barlow

JH: I read that you felt that the work you were making in lockdown, in a way, had no subject. It was very much about the materials and what they offered and how they interacted with your imagination. In some of the works you were looking back to this period a few decades ago, but what were the new things that you discovered through this process that you wouldn’t have known back then?

PB: A kind of ease. I mean, that sounds rather self-satisfying, but that it was easy to make and just to keep going with making. And if things went wrong, they presented themselves as a new departure for that particular work. Whereas, I think way back in the ’60s, if things went wrong, it was an almighty crisis. I mean, it still can be, I’m not denying that, but under those circumstances with small objects where there could be a result in a day, rather than in weeks, it was welcoming how the object unfolded for me, how it kind of told me what it wanted to be, rather than me telling it. I mean, not all the time. Some of them were quite pre-thought in a way, but there was this sort of one thing leading to another and often revisiting other works and doing different versions of them. I wanted to keep the problems to the absolute minimum. So there was some sense of just going into the studio being incredibly easy, rather than it being a kind of dread, which it can be. The studio door can be like a jailer’s.

JH: I know you are talking about this sort of Zen and this return to material and simplicity, but that said, there’s a huge amount of inventiveness and originality and play in these new works. There’s a kind of pleasure in materials that seems quite palpable. It struck me that there was also something almost biomorphic about quite a few of the shapes? I’m interested in how you choose the materials on this particular day, which ones you decide to pick up and play with, and then how do the forms evolve out of that?

PB: One of the works that began was going back to works which I made on these plaster cushions, which were very influenced by Arp and very influenced by Giacometti. I’ve always loved Arp’s work. And I wanted to use these pillows, which bear no resemblance to either of those artist’s work, but they were like a kind of starting point, a space. And in one of these, I was just picking up off-cuts of wood and plywood and two-by-one timber and cutting it down a bit more and joining the two off-cuts together so they were like little posts with shapes on top of them. And I just began planting them in this plaster base on a sort of daily basis. So that work made itself and it also led to thinking of other configurations of works within a particular plinth-like space, and I kept on thinking of Giacometti’s ‘The Palace at 4 a.m.’ I’ve just absolutely loved that work as long as I can remember and I think it’s strange being haunted by another artist’s work.

Alberto Giacometti, The Palace at 4 a.m., 1932 © The Estate of Alberto Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti, Paris and ADAGP, Paris), licensed in the UK by ACS and DACS, London 2021

JH: What is it about that work that you love?

PB: I just think it’s incredibly atmospheric. The whole idea of the palace. The title, ‘The Palace at 4 a.m.’ represents that kind of hour before dawn. But there seems to be these objects hanging in this framework that sort of resonate a mystery as to what that space actually is. It could be anything. It could be the night sky. It could be a building. It could be an architectural thing. It could almost be a landscape or a seascape. So it takes me on a very wandering journey as to what that space is and leaves you... and then sort of abandons you. You just have to make up your mind whether you want to literally pin it down to be something or let it be this very mysterious, open, incredibly fragile space that’s got its own ephemerality as you walk around it. My work doesn’t equate with that, but I was very interested in trying to use these plaster pillows as a kind of predetermined space that I could manipulate a collection of objects on.

JH: In a sense, those sculptures become almost repositories of memory, of influence, of material, of the present moment, of looking forward.

PB: Yes, that’s one way of putting it. Memory and accident as well. I didn’t really buy any new materials at all. I just used off-cuts and things that had already been used. And therefore I don’t see myself as an inventive artist at all, more, sort of, traditional.

JH: I can see the role of tradition in your work, but I beg to differ. I think you’re an extremely inventive artist. I think that the work you make has never been made before and that came from you.

‘…that’s my primary interest in sculpture, that maybe it isn’t 100% visual. It’s about all kinds of longings, the longing to touch, the longing to walk around and still engage. Your movement, your bodily movements, react in 360 degrees of different ways with the thing you’re engaging with. It’s a restless art form that I think is a language that isn’t just specific to objecthood.’—Phyllida Barlow

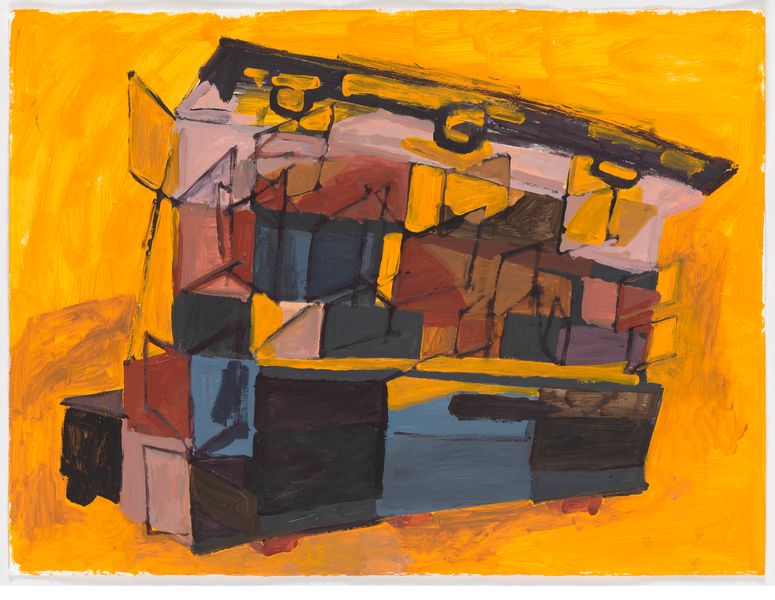

Phyllida Barlow, untitled: nighttimestall, 2013 © Phyllida Barlow

Phyllida Barlow, untitled: underpass; 2020, 2020 © Phyllida Barlow

JH: I’m curious about the role of drawing with your work and if you see the drawings as distinct objects, or are the drawings sketches, a way of working out potential shapes for the sculptures?

PB: They cross the entire repertoire. Sometimes they’re almost... They are like paintings. I think the ones in the Zurich show are, in a way, closer to painting than they are to sculpture. But then, of course, they overlap—to me, Rothko is one of the greatest sculptors ever born.

JH: Please elaborate. What do you mean by that?

PB: When the Tate Britain had the Rothko room, I don’t know if you remember it?

JH: Yes, I do.

PB: I always thought that it had this sculptural language. I mean, sculpture just isn’t always the object. It’s a language which can be as much a snowstorm as it can be a heavy physical lump, if you know what I mean? And I think the presence of those, Rothko’s paintings, the whole chorus of them with the sort of brooding colors coming and going, wasn’t about being able to name anything. And I suppose that’s my primary interest in sculpture, that maybe it isn’t 100% visual. It’s about all kinds of longings, the longing to touch, the longing to walk around and still engage. Your movement, your bodily movements, react in 360 degrees of different ways with the thing you’re engaging with. It’s a restless art form that I think is a language that isn’t just specific to objecthood.

JH: Speaking of architectural space and this fusion of sculpture, painting and things that are ephemeral, such as music, for example, but are also sculptural, you’ve recently designed the stage set for Mozart’s 1781 opera, ‘Idomeneo.’ This tells story of the King of Crete and will be staged at the Prince Regent Theater in Munich later this year. Is this the first time that you’ve designed a set for an opera?

PB: It’s actually the second time. The first time was in 2000 at Wimbledon Theatre, their sort of small, experimental theater, for a play called ‘Knives in Hens.’ It was a budget of 400 pounds I think, and I had no idea how to set about this, but was thrilled by it. I ended up using the whole stage as a sort of sculpture installation and had to learn immediately that I had left no space for the performers.

‘I’ve always wanted there to be three things in my larger sculptures, which is very theatrical, where the sculptures, the space and the audience are all protagonists and all, in a way, share some equality in how they experience the work.’

Phyllida Barlow’s set design for the production of ‘Knives in Hens’, commissioned by the Attic Theatre Company, Wimbledon Theatre, London, 2000 © Phyllida Barlow

PB: For this ‘Idomeneo’, the director of the Bayerische Staatsoper did a studio visit and said all he wanted was the sculpture that went on the stage, which was a sort of incredible invitation. A whole string of artists such as George Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer and Marina Abramović have previously been invited to work there. I’ve been working with two young designers who’ve actually helped me do this translation from a sculpture into a stage set. It’s been an incredible experience with the workshops in Munich. I’ve tried to hold on to the sculptural aspect within the stage sets. Rather than them being designs, they are fully blown sculptural objects. I’ve always wanted there to be three things in my larger sculptures, which is very theatrical, where the sculptures, the space and the audience are all protagonists and all, in a way, share some equality in how they experience the work. It sounds very idealistic, but that the actual physical sculptures are not the only thing that are playing a part. So being in an actual theater where that can be played out as an actual conscious reality is an extraordinary experience.

JH: And what was your process of coming to a sculptural form that has been filtered through music and also this very powerful story of ancient Crete?

PB: When the director of the opera, Antú Romero Nunes, who is an extraordinary, experimental director, came to the studio, he saw the whole of the opera as theme about young against old. For me it is a kind of stand-off between fantasy—the fantasy world of the gods—and the reality—emotional worlds of the human beings. So we’ve been able to kind of fuse those two positions and also the interventions of nature, which are fascinating. So much has become incredibly relevant to what we’ve all been through globally this year. It’s been quite extraordinary. For me, the story is a grand metaphor for the need to believe in something and then the need to apply emotional realities to the morals of those beliefs and how things become a tangled mess as a result, and to Nunes’ approach as being the need that younger generations have to clear away the cobwebs that older generations leave behind them. The four objects I’ve proposed have symbolic qualities and are a lot to do with the sea. I’ve made what are called breakwaters—those groins that go out to the sea to try and stem the flow of the tides. There’s a huge lookout post, which is something that used to be along the coasts of the UK years ago and were used to spot vessels at sea that might have been in trouble, but are no longer in use. And then I’ve made this vast rock which is sort of supported on a whole network of props. I suppose it is the most dominant thing. And I think, in terms of the story, it represents something that has a sort of permanence, is a kind of witness to change in the way geology is. The fourth component are these structures that industrial and architecturally like architecture brut. So these four components have these various different roles throughout the opera.

JH: Were you a Mozart fan before getting this offer?

PB: Yes. I do absolutely love music, classical music though. I always feel rather embarrassed. I remember when we were listening to Wagner’s Ring cycle once, my son came in and said, ‘Oh, for God’s sake. This sounds like the worst kind of film score.’ And of course he’s right, in a way.

‘untitled: 11 awnings’ (2013) in Barlow’s exhibition ‘scree’ at Des Moines Art Center, 2013 © Phyllida Barlow. Photo: Paul Crosby

JH: Your major survey show ‘frontier’ is opening in Munich at the Haus der Kunst this March. Why that title? Where did that come from?

PB: I think I like the edges of things. I like the fact that one sculptural problem can be finding the edge of the work. If you think of an artist like Medardo Rosso, I always think the edges of his sculptures are very nervy. There’s a sort of nervousness about where the periphery of the work is.

‘I’ve always found how to finish a work quite difficult, as though I could go on and on forever finding that edge’

Also in thinking about Bruce Nauman’s sculptures from the 1970s—not his neon works or his videos, but the actual objects—there was that same sense of finding a boundary to the work and being very conscious of its physical presence as a kind of set of prohibitive edges, and how you approach the work. Franz West, even Eva Hesse, I think, is a wonderful artist where the edges and boundaries of the work are very considered, but they’re also trying make that edge nervous or, in a way, unpredictable. I’ve always found 1) how to finish a work quite difficult, as though I could go on and on forever finding that edge and 2) an interest in how the work, if it does get to a venue, what its controlling factor is. What is permissible about it and what is actually forbidding about it? And that seems to me to be a kind of frontier to our own bodily cells in relationship to another bodily self that is static.

JH: It’s very relevant too to the times we live in, this idea of a frontier. The frontier of the body and how the pandemic is making incursions into our private spaces.

PB: I think it’s always present, in terms of our psychology as human beings. Are we the sort of person who prefers a short conversation to a stranger on a railway platform or are we a person who needs friends? And I think they are quite psychologically different types. It doesn’t mean to say the person who likes those conversations, chance meetings, on a railway platform doesn’t have friends, but there’s something exhilarating about a stranger and yourself suddenly having completely the same view about an incident that may have happened or an observation or something. And then that’s it. On the other hand, friendships are more complex and demand more handling, in a way, of oneself in relationship to them. I think those are kind of incredible psychological frontiers that we’re sort of dealing with on a daily basis, really.

Phyllida Barlow, Object for the television, 1994 © Phyllida Barlow

Phyllida Barlow, untitled: hanginglump, 2, 2012 © Phyllida Barlow

JH: What determined the choice of works in this show, ‘frontier’?

PB: A lot of discussion with the curator, Damian Lentini, as well as many other factors— which works were where in the world, the dreaded shipping costs—which in the end meant that the original works were edited quite severely to the current list of works, which is still considerable. The main intention from my point of view was to show as many of the different tropes that I’ve explored over the last 10 to 15 years, to have some evidence of all those different ways of working at height, working on the ground, working with formlessness, working with form, so that there was this representation across the board.

JH: And it includes works that you’ve made in lockdown?

PB: Yes, it includes four, large, completely new works. And a remake from 1975.

JH: I’m very interested in this idea of remaking work. What is the thinking around that?

PB: I did a work called ‘Shedmesh,’ that was at the time very much influenced by Arte Povera anti-form and my interest in trying to find ways of making that were outside the kind of laborious techniques that I had been taught at art school, all of which I’m extremely grateful for, but at the time I wanted to completely renounce. I’d been looking at the incredible Polish weavers at that time, working in communist Poland and producing these huge edifices of tangled rope and twine and hessian. One artist was using steel thread, and producing these massive structures. I was completely overwhelmed looking beyond the British footprint of sculpture, which I’ve had an on-and-off relationship with all my life.

Phyllida Barlow and her daughter Clover Peake in front of ‘Shedmesh’ at the Camden Arts Centre, London, 1975

So I built these grids. The original ones were made out of old painting stretchers that were being thrown out by the Slade. Someone there rang me and asked if I wanted them, and I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll take the whole lot.’ I very crudely tied and nailed together the painting stretchers. And then bound each one in padded canvas strips. So you’ve got a sort of clash between the grid-like shape of the canvas stretchers and this random tying of the canvas and foam strips. I built those up into this cube and that is what will be on show in one of the galleries. We remade it. I and an assistant remade it. She was absolutely brilliant. I couldn’t have done it without her.

JH: Did it change at all?

PB: Oh, yes, it changed. There was no way I could get hold of old painting stretchers.

JH: So what did happen to the original work?

PB: Oh, I reused all the bits in everything else.

JH: In a way it’s not so much a remake as... It’s that idea of renewal within repetition, the idea of taking a form and remaking it, but it becomes something new in the process.

PB: Yes. I mean, if you put a photograph of the original against it, you would see the relationship very clearly between the two.

JH: It makes me actually think of the paintings of Morandi.

PB: Oh, yes?

JH: The idea that he’s looking at this still life that he often wouldn’t change for months or even years, and keeps repainting supposedly the same painting. But, of course, each painting is very different with a very different mood.

PB: Oh, that’s wonderful. That’s such a wonderful thing to hear.

JH: I really hope I can get to see your Munich show because it sounds absolutely amazing. And what an important and extraordinary celebration of your career so far.

PB: Yes, it is. When I first started out, left art school and thought, ‘This is it,’ I didn’t think of a career. I just thought this was something I have to do for the rest of my life and I have no idea how it’s going to turn out.

Phyllida Barlow’s survey exhibition ‘frontier’ opens 5 March at Haus der Kunst, Munich. Her exhibition ‘small worlds’ is on view at Hauser & Wirth Zürich, 6 February – 14 May 2021. Jennifer Higgie is editor-at-large of ‘frieze’, and is based in London. She is the host of the podcast, Bow Down: Women in Art History. Her book ‘The Mirror and the Palette’ is forthcoming from Weidenfeld & Nicolson.