Essays

How To Peel an Orange

Art critic Waldemar Januszczak recalls a poignantly fruitful afternoon in Chelsea

I interviewed Louise Bourgeois in 1998. Well, I say I interviewed her. It was more a case of pressing the button on the camera and seeing where she took us. She was 87 then, far past the age where you can to be led in your thoughts by some guy from Britain who turns up at your house with a film crew.

I was making a series for Channel 4 television called ‘The Truth About Art.’ The series included three films—one about God, another about animals and the third about sex. Louise, I calculated, had things to say about all of them. But mostly I was interested in sex. We spent the morning filming her work at a New York gallery, taking an especially long time over ‘Janus Fleuri’ (1968), the double-sided bronze penis-vagina that hung from the ceiling. It seemed to encapsulate things. Also, since my name is Januszczak, I felt a kinship with it. Like the Roman god, Janus, the penis-vagina pointed two ways. We got to her house in Chelsea in the afternoon. It was a narrow brownstone, straight out of an episode of ‘Kojak,’ with stairs leading up to the front. Jerry Gorovoy, Louise’s longtime assistant, with long black hair, met us at the door. The house was wonderfully chaotic. Peeling walls. Broken floorboards. Stuff everywhere. To me, it all felt powerfully European—not unlike my own mother’s house. The kind of house you have when appearances are the last thing on your mind. The interview was fine. She talked about whatever she fancied. And when we’d finished, I asked her if she could do the thing with the orange that I’d read about, in which she peels the skin into the shape of a human figure. That morning, I’d gone in search of the perfect orange. It had to be bright and firm, with a thin skin that was easy to peel. I eat a lot of oranges myself, so I knew what I was looking for and found it in a deli next to the hotel. I bought a couple, just in case. Which turned out to be a very good idea. Louise was happy to oblige. She sent Jerry off to find a scalpel knife. To save time, the cameraman advised us do it in two stages. First, Louise should get one of the oranges ready to peel. Then, with the other orange, she should draw the figure and tell the story about her father: how he taught her the trick, why it was creepy. So that’s what we did. My hand appears in the film passing her the second orange. You hear me twice. Once, saying ‘yes’ when she asks sternly if I’m looking. And then, at the end, telling her it was ‘brilliant.’ Because it was.

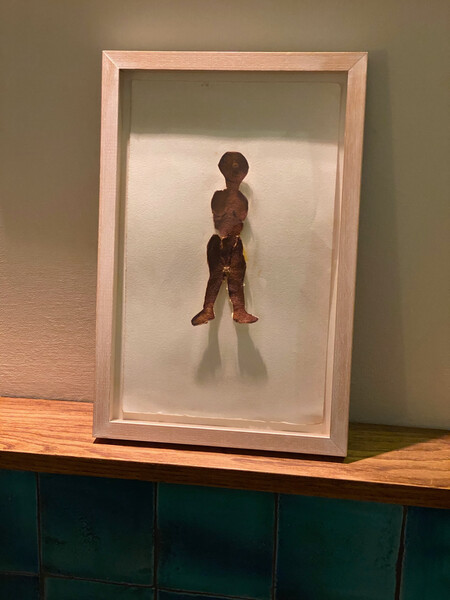

‘When I got home, I had [the orange man] framed, and put him on my mantlepiece. He’s still there, exuding his creepy European voodoo.’—Waldemar Janusczak

Louise Bourgeois’ gift to Waldemar Januszczak © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY. Photo: Waldemar Janusczak

When we finished the filming, she asked us if we were hungry. The crew said yes. So she went into her tiny kitchen, pulled out a can of tomato pasta, and heated it up on a little gas cooker she had in the back. It was warm and motherly of her and very European. My mother would have done the same. On the way out, I asked if I could take the orange man home. So she told Jerry to find me some paper to put it in. I was worried about the penis getting flattened, but in the end it was the penis that kept him attached to the paper. When I got home, I had him framed, and put him on my mantlepiece. He’s still there, exuding his creepy European voodoo. We filmed on real film. One day, I’d like to show it on a flickering old projector, so you can really see the beautiful colors, and the beautiful sight of Louise Bourgeois peeling an orange.

Waldemar Januszczak, one of Britain's most distinguished voices on art, is chief art critic for The Sunday Times and previously held that role for The Guardian. He has twice won the Critic of the Year award. For more than two decades, he has also produced films for television, including ‘Picasso: Magic, Sex, and Death,’ with Sir John Richardson (2000) and ‘The Renaissance Unchained’ (2016.)

This winter in Gstaad, important sculptures and drawings by Louise Bourgeois are on view at Tarmak22 in the exhibition ‘The Heart Has Its Reasons,’ 19 December 2020 – 3 February 2021.