Conversations

Confronted with a Choice

A Discussion about the Radical Work of Gustav Metzger (1926-2017): Daniela Pérez and Mathieu Copeland, Moderated by Randy Kennedy

Installation view, ‘Gustav Metzger: Decades 1959–2009’, Serpentine Gallery, London, UK, 2009. Photo: © 2009 Jerry Hardman-Jones. All images: © The Estate of Gustav Metzger and The Gustav Metzger Foundation

In ‘Art Strike of 1977–80,’ Gustav Metzger's radical appeal to fellow artists issued in 1974, Metzger wrote: ‘The refusal to labor is the chief weapon of workers fighting the system; artists can use the same weapon.’

Metzger, one of the most politically determined artists of the 20th century, operated along the bipartite lines of destruction and creation. The final moments from a video capturing a now-famous performance in 1961 on London's South Bank—the first public demonstration of Metzger’s revolutionary concept of auto-destructive art—show the artist drift off-screen, with the remnants of flapping, burnt nylon sheets framing the city skyline beyond it. Metzger’s work treads this fine line between a radical politics and a formal commitment to challenging the boundaries of art and aesthetics. In defiance against the capitalist art object, Metzger advocated for an art that held a mirror up to the darker shadows permeating our society. After the Holocaust, he affirmed, beauty must prevail. Metzger’s stringent political beliefs evolved and remained ideologically consistent up until his death in 2017. By that point, his idealist efforts were concentrated on fighting man-made extinction. Two curator-editors and personal acquaintances of the artist talked recently to Randy Kennedy, about these complexities and about the encounters that formed Metzger’s inimitable character and 60-year practice.

Randy Kennedy: I was hoping we could start by talking about Metzger’s work and the example of his lifelong activism in the context of what we’re all living through right now—humanity under siege by pandemic, economic instability, social upheaval and unprecedented worldwide protests.

Mathieu Copeland: Thinking about this moment of course brings me back to one of Gustav’s key writings, from 1974, in which he called for up to three years without art, from 1977 to 1980, which became known as the Art Strike—an appeal for all artists to withdraw their labor completely. As we experience a global pandemic, one cannot help but go back to that and look into why he was making such a radical proposal. He was hoping that in doing so, the art system, the art market, the art press, would crumble, and a new kind of art might emerge, at least a new engagement between art and artists, and the world could be reshaped. Over the past five months, we've experienced many different types of closures in the world at large and in the art world, which in a sense have brought a version of his petition into reality, though for very different reasons. Seeing what we’re seeing now, you realize that his writings continue to shine through and give us some tools for analysis of what we’re experiencing.

Daniela Pérez: This makes you realize that basically everything he was bringing up beginning in the late 50s, through to the 60s and 70s—mass nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience to confront the threat of war, of nuclear annihilation, of environmental degradation—is not in the past. It’s all still fully with us today.

RK: The causes of the pandemic aren’t fully known yet but it seems the likelihood is that it is a fallout from the ways in which we force the natural world to serve our needs, particularly as regards the food supply. We keep nature in sort of a box, under an increasing amount of pressure, and often now there are eruptions—nature bursts of out the box and takes its own course in unexpected ways. Metzger wrote about and made work about humanity’s enormous capacity for destruction, almost like a Freudian death drive. Could you both talk about his focus on destruction, so early on, complimented by the idea of auto-creation?

MC: The idea of destruction comes first. The first mention of the term in his writing is 1957, in connection with the exhibition ‘Treasures from East Anglian Churches’ that he organized in King’s Lynn in Norfolk, where he was living at the time, working as a second-hand book dealer. He was obsessed with the idea of art being destroyed or defaced, and he organized a show in the Crypt of an old merchant’s house, gathering medieval artifacts such as stained glass and grotesque corbels, church art that had been damaged or defaced during the Reformation. But destruction of course was something very much rooted in his past, in his upbringing in Nuremberg, having survived the Holocaust while most of his family did not. In 1959 with his very first manifesto, he puts forward a very strong and powerful analysis, not only about art but also about society, a commentary on a society of excess.

DP: I think that from that very early moment—a breaking point in his career, when he left painting behind—he was already taking a stand, rejecting the indifference and resignation that permeated society. Even earlier, he expressed this through the use of particular materials inherent to mass consumption, like cardboard containers, wrappings, newspapers, garbage bags.

Gustav Metzger (detail; 1960), Ida Kar © National Portrait Gallery, London

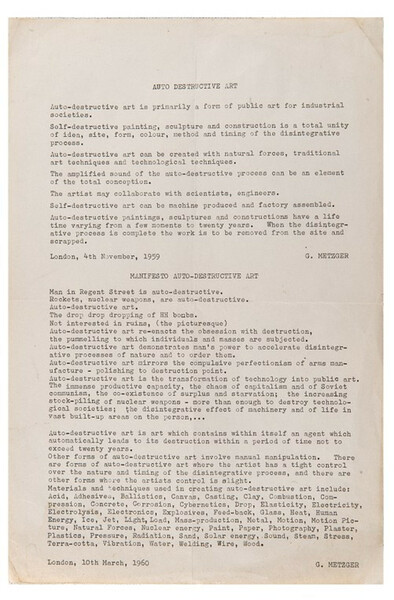

Gustav Metzger, ‘Auto-Destructive Art / Manifesto Auto-Destructive Art’, March 1960

RK: I’ve always wondered about crosscurrents between Metzger and Jean Tinguely. In 1960 Tinguely staged ‘Homage to New York’, his self-destructing sculpture, in the garden at the Museum of Modern Art, and the following year Metzger staged his first public demonstration of self-destructive art on the South Bank in London, spraying acid onto nylon sheets while clothed in gas mask, goggles and hard hat.

MC: The connection between them was actually pretty strong. Gustav was already very aware of the New Realist movement, which Pierre Restany had formed in the summer of 1960. And he was friends with Daniel Spoerri, one of the members of the New Realists along with Tinguely. Spoerri told him of Tinguely's intention to do ‘Homage to New York,’ which was one of the reasons why Gustav rushed to have the first manifesto of self-destructive art printed in 1959. I don't want to make it sound as though they were rivals—they were extremely aware of one another. What's interesting is that they did not meet in person until the late 1980s. And of all places, they met each other at Art Basel! Tinguely was introduced to Gustav, and when he heard that it was him, he started screaming—this is what Gustav told me—‘He wrote the manifesto! He wrote the manifesto!’ And that was their only encounter.

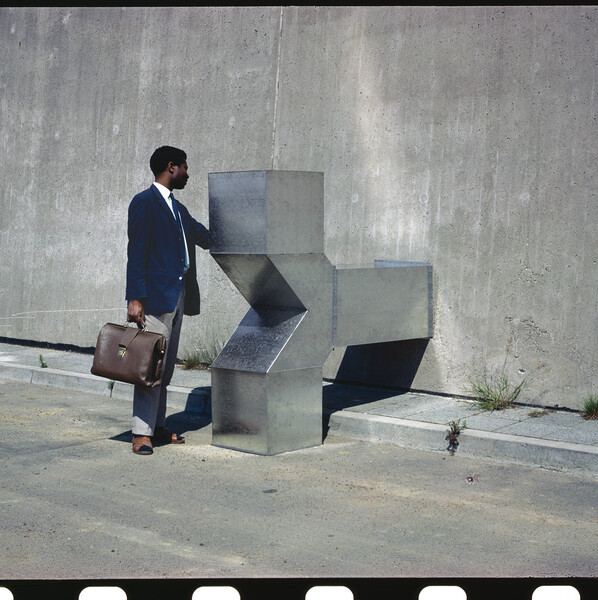

Still from documentary portrait of Gustav Metzger made at Regent Street Polytechnic 1965. Dir. by H. Liversidge

Still from documentary portrait of Gustav Metzger made at Regent Street Polytechnic 1965. Dir. by H. Liversidge

RK: In terms of motivations for making self-destructive art, it seems to me that Gustav’s work grew out of an overarching philosophical and political program, whereas, with Tinguely’s work, that wasn’t as much the case—it was more formal, about the possibilities of movement and kinetic energy.

MC: I cannot talk about all of Tinguely’s motivations at the time. But it is true that Gustav was extremely informed from the beginning by his politics and activism, which date to as early as the 1940s. He went to live in anarchist commune while still in his teens. He became a vegetarian. He joined the anti-war group the Committee of 100 along with Bertrand Russell and other figures. So, his political activism was always there and extremely strong. But it should be said that both he and Tinguely approached the idea of destruction and creation fully through the prism of art.

[Metzger’s] art had a fundamental relationship with the development of political systems whose rhetoric had led to the Holocaust and to the atomic bomb. It was engaged with the global threat that such systems posed—Daniela Pérez

DP: I think for Gustav it was very clear that his art had a fundamental relationship with the development of political systems whose rhetoric had led to the Holocaust and to the atomic bomb. It was engaged with the global threat that such systems posed in the development of technologies that would not only pollute the interrelationship of humans, but also the environment, and that could of course lead to the annihilation of diverse living beings.

RK: The fact that he trained as a painter, under David Bomberg, and began his art life as a painter seems almost hard to believe given what came later in his career, though it’s hard to think of any postwar artists who didn’t begin one way or another in painting.

DP: When Gustav performed the auto-destructive art demonstration in 1961 on the South Bank in London, it was really much more sophisticated than it seemed and among other things, addressed the history of painting. At least I see it that way. He was ‘painting’ with hydrochloric acid on nylon canvases, which sounds simple, in a way, but it was not. It was taking place outside, in front of people. He was dressed up in a very particular way, with the gas mask, and he was using every element in a very thoughtful and symbolic way. When the painting starts to disintegrate under the acid, what you see in the film is what is beyond the canvas itself, the backdrop of the London skyline. I can’t imagine what people who were there witnessing the event must have had going through their minds. It wasn’t something other artists were doing, in public or in private.

Gustav Metzger, Painting on Cardboard, ca. 1957-8

Gustav Metzger, Untitled Painting (Abstract), ca. 1958-9

MC: Gustav told me that he got the idea of spraying the painting, instead of brushing it, from the conceptual painter John Latham, who began using a commercial spray gun for painting as early as the mid 1950s. The idea of paint going onto the paper without one touching the other, without fully controlling either to generate the art, was something that Gustav was extremely keen to address himself, thinking about how he could distance himself from the canvas and nonetheless put the acid onto the nylon.

RK: Looking at the film now, the use of the gas mask really seems like a major element of the entire demonstration–a very powerful symbol, in the way that you mentioned a minute ago, Daniela. Looking at the protest and police images coming out of Portland and Seattle and some other American cities right now, it’s the ubiquitous face-covering gas masks worn by federal agents and other riot police that signal a real escalation, a move into what begins to seem like military territory—gas masks being a symbol of the horrors of modern warfare going back to World War I.

With Gustav there was always sense of the operatic in the making of a statement … He focused on elements that would trigger strong elements of recognition and response. He was indeed a man struggling with society and with art—Mathieu Copeland

MC: With Gustav there was always sense of the operatic in the making of a statement. For instance, when you see an image of him working on the acid demonstration in his studio in King’s Lynn, when he did the first test of the work, he had just a little metallic brush that he used to apply the acid onto the canvas. But when it came to the South Bank art demonstration, he focused on elements that would trigger strong elements of recognition and response. He was indeed a man struggling with society and with art.

‘Gustav did an action in front of the Haywood Gallery where he literally put nature in a box, where he put a tree into a box fuming with the exhaust fume of a car. Killing nature, really.’—Mathieu Copeland. (Recreated here in ‘We Must Become Idealists or Die’, Museo Jumex, Mexico City, Mexico, 2015)

Charlotte Posenenske, Vierkantrohre Serie D (Squaretubes Series D), Offenbach, 1967. Courtesy the Estate of Charlotte Posenenske and Mehdi Chouakri Gallery, Berlin

RK: Daniela, could you talk a bit about his evolution in thinking about whether any works of art should ultimately persevere—be in museums, be bought and sold, end up as commodities, fetishized in museums. It seems that his thinking changed somewhat throughout his life, along with this thinking about remaining in the art world, as opposed to leaving and remaining only in the world of activism. In his context, I sometimes think of the great German painter and sculptor Charlotte Posenenske, who left the art world for good in her late 30s and instead became an occupational sociologist, because she no longer believed that art could effect any meaningful change for good in the world.

DP: I think Gustav was very consistent, ultimately, but it evolved. And it evolved quite a lot. When I was confronted with the challenge of putting together a show for an artist who doesn't have physical works in the traditional sense of that idea, I had work around that fact in many, many, many ways. And that involved, of course, Gustav’s decision about not shipping artworks, not doing things to unnecessarily contaminate the environment, many other things that were part of his artistic principles. But I would say that towards the latter years of his life, he was aware that certain processes of documentation and archiving needed to be preserved if the work was to have impact, to be able to communicate, to effect any change beyond his lifetime too.

Daniela Pérez with Metzger in 2012. Photo: Mathieu Copeland

Installation view, ‘Gustav Metzger. WE MUST BECOME IDEALISTS OR DIE’, Museo Jumex, Mexico, 2015. All images: © The Estate of Gustav Metzger and The Gustav Metzger Foundation

MC: If you go back to his early history, in 1953, when he was a student of David Bomberg together with Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff, Gustav had been instrumental in forming with fellow students the ‘Borough Bottega’, a kind of art collective, and organizing an exhibition of their works at a commercial gallery. However, by 1959 and 1960 he was adamantly against the art market, against the commercial side of the art world. And when you look at his fourth manifesto, distributed in 1962 at the ICA in London in connection with the Festival of Misfits, the incarnation of the first Fluxus event in London, there you find one of his most vehement statements against art dealers. [‘The artist must destroy art galleries. Capitalist institutions. Boxes of deceit.’] I adore these lines. Throughout his life, he had decided to stay away from the art market and from the galleries especially. However, that did not imply that he would not go and see exhibitions there—quite to the contrary. He was an avid consumer of them. He was just extremely aware of commercialism and the relationship that the artist has with the world.

DP: With museums and other types of institutions, he was very, very critical and very analytic about whom he collaborated with. When I met him, and Mathieu was also there at one of those times, he had come up with some very exacting questions about the organization, about how it was put together, about where its money came from. He wanted to be part of an understanding that would allow him do work that, for him, would be consonant with his own way of thinking, not to collide with his thinking. I remember him talking about the work of an artist to support himself as being similar to that of an architect. He was in favor of artists being paid like architects are paid, for projects. Towards the latter part of his life, I'm sure that position enabled quite a few projects to continue.

MC: There’s a beautiful line in ‘Years Without Art’ in which he says that some artists who make a living from their art would have the wealth to survive. But as most artists do not making a living from their art, they do other things to make ends meet. And so a three year strike wouldn’t affect them whatsoever. The main part of the system that would crumble would be the art magazines, the museums and cultural institutions, the galleries, the auction houses, and all those dealings in works of art. He had a very powerful position on how to survive and what should and shouldn’t survive. And it’s remarkable to find an artist who stayed within such a philosophy, who decided to work mostly outside of the art-market system and who nonetheless found ways to make it and make an impact. And yes, that doesn’t mean that he didn’t sell some works, but he would sell them directly to an institution or a museum. And that would be it. Even though that happened only towards the very end of his life. He lived a very frugal life and that’s something really to be admired.

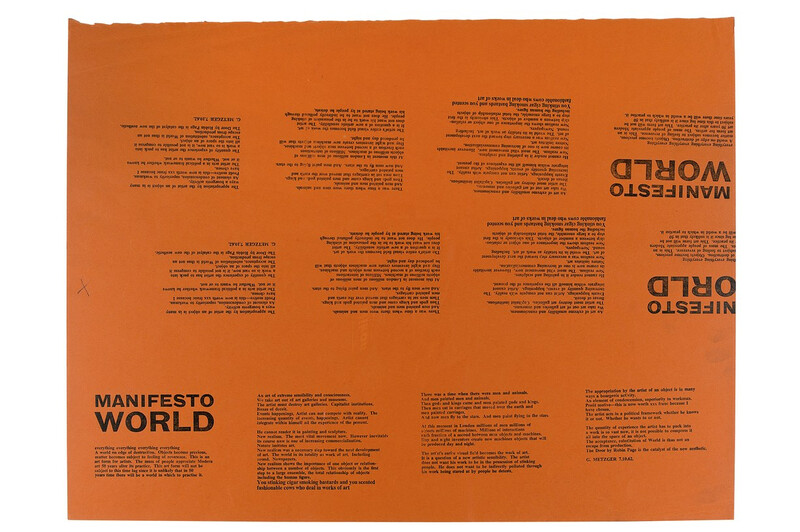

Manifesto from 1962, first distributed at the Misfits evening at the ICA London the same year.

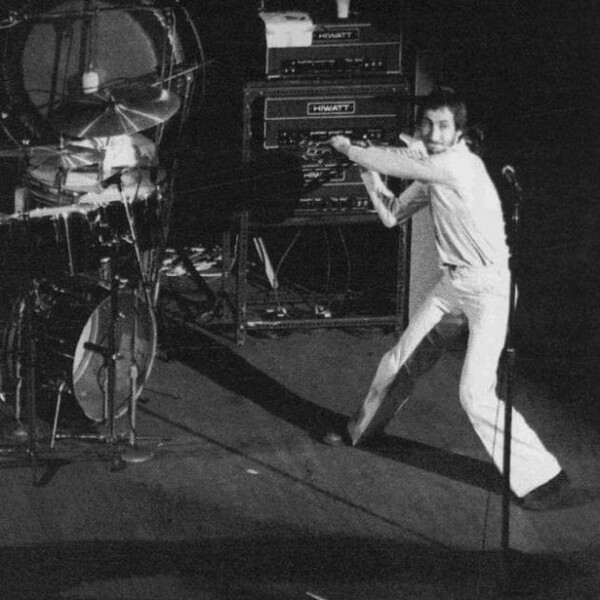

Pete Townshend of The Who studied under Gustav Metzger at Ealing School of Art and was inspired by Metzger to smash his guitar on stage.

DP: I asked him once why he hadn’t decided to just leave the art world, even the mainstream world entirely, and go live elsewhere, away from society. And he responded that such a refusal wouldn't have made sense at all for him. He said he needed to be part of society in order to make a difference within it, and he wanted to deal with our problems in order to be able to generate whatever change he hoped he could bring about. In the end he found the correct forms, or what for him were the correct forms—through writing, through calls to action, through symposia and through works of art—to further his interest in healing the world.

MC: What’s also wonderful about his position both within and against society is—for instance—you talked about putting nature in a box at the beginning. Well, Gustav did an action in front of the Haywood Gallery where he literally put nature in a box, where he put a tree into a box fuming with the exhaust fume of a car. Killing nature, really. That freedom he had to critique the art institution, he really took it everywhere. He would attack on a par, on a similar stance, both the commercial gallery world and the museum in order to really make his point as an artist. I think that freedom is rare, and something to really be admired nowadays.

RK: On a final, slightly lighter note, I’m wondering whether either one of you ever talked to him about his erstwhile student, the rock-and-roll-star Pete Townshend, who has said that it was Gustav’s work that first inspired him to smash guitars on stage—an act that has become part of the bedrock of the supposedly seditious genre.

MC: It was actually kind of a beautiful connection that I know Gustav loved. Pete attended a lecture by Gustav at the Ealing School of Art in London, where he was a young student. And he said that the radical thinking in this lecture inspired him to try to create a kind of music that would last only for the time of a concert, never to be repeated. And destroying your own instruments would be part of that. Of course, as he recognized, success very quickly makes such a dream sadly impossible. – The preceding were edited and condensed portions of a conversation that took place on 27 July 2020.

Daniela Pérez is a contemporary art curator based in Mérida, Yucatán in Mexico. She is currently curator at TAE Foundation. Between 2015 and 2017 she was deputy artistic director at Museo Tamayo in Mexico City. In 2015 she curated the exhibition, ‘We Must Become Idealists or Die. Gustav Metzger,’ at Museo Jumex. Pérez writes regularly for art magazines and catalogs, and has taught at the art schools of La Esmeralda and Soma. She studied art history in Mexico City and obtained a master’s degree in contemporary art curation from the Royal College of Art, London.

Mathieu Copeland has been developing a curatorial practice that seeks to subvert the traditional role of exhibitions and renew our perceptions of them. He edited the publication ‘Choreographing Exhibitions’ (Les presses du réel), and co-edited the radical anthology ‘The Anti-Museum’ (König Books). Copeland has organized, among many other exhibitions, ‘VOIDS. A Retrospective’ in 2009 at Centre Pompidou and Kunsthalle Bern and ‘the exhibition of a film’ an exhibition as a feature film for cinemas in 2015. He is most recently the editor of ‘Gustav Metzger: Writings (1953-2016)’, an anthology of more than 350 texts that defined the artist’s worldview and work.

Randy Kennedy is the director of special projects for Hauser & Wirth and editor in chief of Ursula magazine. For 25 years, he was a reporter for The New York Times, more than half of that time writing about the art world. His first novel, ‘Presidio,’ was published in 2018 by Simon & Schuster.