Books

Resilience: Philip Guston in 1971

by Musa Mayer

I’ve found no better word than resilience to describe that particular year in my father’s work and life, and indeed to characterize his entire life, especially his early life, when he discovered the great art and artists of the past and quite literally drew and painted a new identity for himself, leaving behind—but never fully escaping—a family beset by tragedy.

By 1971 my father had already devoted forty years to his passion for painting. His successes as well as his frustrations with the art world informed his confidence in his own capacity and resources. ‘At the heart of resilience is a belief in oneself,’ states an article exploring the psychology of the term. ‘Resilient people do not let adversity define them. They find resilience by moving towards a goal beyond themselves.’[1] – The crucial role of the year 1971 in Philip Guston’s oeuvre can only be fully understood in light of what had occurred the year before, when the first exhibition of his new figurative paintings from 1968 to 1970 opened on October 17, 1970, at Marlborough Gallery in New York City. Today, the critical rejection of these late paintings, now acknowledged as the culmination of his career, is a familiar story in the lexicon of twentieth-century American art. Philip Guston has been mythologized as an artist impervious to criticism, steadfast in his focus. But like any artist, he was human and vulnerable, in need of sources of renewal and support to sustain a lonely studio practice and to endure the forays into the dark places in his psyche from whence these images emerged. The story that hasn’t yet been told is how he stilled those critical voices and was able to continue his work.

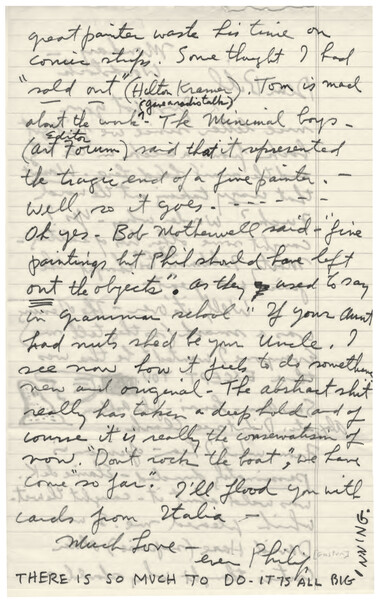

Letter to Bill Berkson, October 19, 1970 © The Estate of Philip Guston

Given the complete reappraisal of his late work since his death nearly forty years ago, it may be difficult today to comprehend what a courageous act it was for my father to exhibit these ‘crude’ and ‘cartoonish’ works, as they were then viewed. At the time, most critics saw the new Guston paintings as an outrageous departure from his abstract work of the 1950s and 1960s, not at all in line with the critically sanctioned Color Field and Pop Art of the day.

‘When de Kooning saw the show, after embracing me, and congratulating me, he said: ‘You know, Philip, what your real subject is? It’s freedom!’

Most of the art world—including many of the other painters he knew—was shocked and dismayed by what they saw at Marlborough from an acclaimed painter associated with elegant abstractions. Yes, Guston’s painterly qualities were still present, but these funky hooded figures horrified the critics. The response was resoundingly negative. Reviews were filled with words ‘clumsy,’ ‘embarrassing,’ ‘simple-minded,’ and ‘an exercise in radical chic.’[2] Decades later, critic Peter Schjeldahl vividly recalled his initial shock of the Marlborough paintings, ‘It was as though an elegant veil had parted and out had stepped a yakking geek.’[3] Robert Hughes, TIME magazine art critic, entitled his review, ‘Ku Klux Komix.’[4] Recalling the Marlborough opening in a 1980 interview, my father said: ‘But there were some who understood. When Bill de Kooning saw the show, he said he liked it very much. You know, everybody thought those paintings were about the hooded figures, and the bad conditions in America, and so on, and that was part of it—every artist hopes to give his own interpretation of the world—but they were about something else, too. When de Kooning saw the show, after embracing me, and congratulating me, he said: ‘You know, Philip, what your real subject is? It’s freedom!’’[5]

Philip Guston, with Willem de Kooning (right) and James Rosati (left), at the Marlborough Gallery opening, 1970. Photo: Steven Sloman

A few days after the opening, my father wrote to his friend, the poet Bill Berkson, who had just published an essay for Art News on the new work: ‘From what I hear—opinion is passionately divided—Elaine de K. [de Kooning] was wild about it—caught the wit—which pleased me. So was David Hare (surprise). Older critics thought, why should a great painter waste his time on comic strips. Some thought I had ‘sold out’ (Hilton Kramer). Tom [Hess] is mad about the work (gave a radio talk). The Minimal Boys— Editor Art Forum—said that it represented the tragic end of a fine painter.—Well, so it goes—Oh yes. Bob Motherwell said— ‘fine paintings but Phil should have left out the objects.’ As they used to say in grammar school, ‘If your Aunt had nuts, she’d be your Uncle.’ I see now how it feels to do something new and original. The abstract shit really has taken a deep hold and of course it is really the conservatism of now: ‘Don’t rock the boat, we have come so far.’’[6] But the letter ended with these words all in capital letters:

‘THERE IS SO MUCH TO DO—IT IS ALL BEGINNING!’

A Day’s Work, 1970 © The Estate of Philip Guston

[...] My father showed slides of the paintings of large hooded figures from the 1970 Marlborough show to the students at the Yale Summer School of Music and Art at Norfolk, Connecticut, the year after his return from Italy, in August 1972: ‘I went to Europe right after this work. The show opened and we went to Italy for about seven months. I’m an Italianate. That is to say, I love Italy. I’m not Italian, but I love Italy. I’ve been there many times, just loving it. And I wanted really to see early frescoes of Last Judgments and end-of-the-world paintings. Particularly Romanesque paintings and Sienese fresco painters who paint huge marvelous frescoes of the damned, all the tortures in hell, and so on. Heaven is always very dull, just a lot of people lined up. Like trumpets, they’re all lined up. There’s not much to look at. But when they’re going to hell the painter really goes to town. All kinds of marvelous stuff. That’s when they really enjoyed painting. So, I feel we live in comparable times. Oh yeah, and I want to paint that. I don’t want to copy, but I feel that’s the big subject matter. I don’t know how it’s going to come out. Well, I’ve begun. I’ve begun with this story.’[7] Italian art and culture had been a touchstone for my father since his boyhood in California, when he’d pored over art books from the public library, making painstaking copies of Michelangelo and Masaccio drawings.

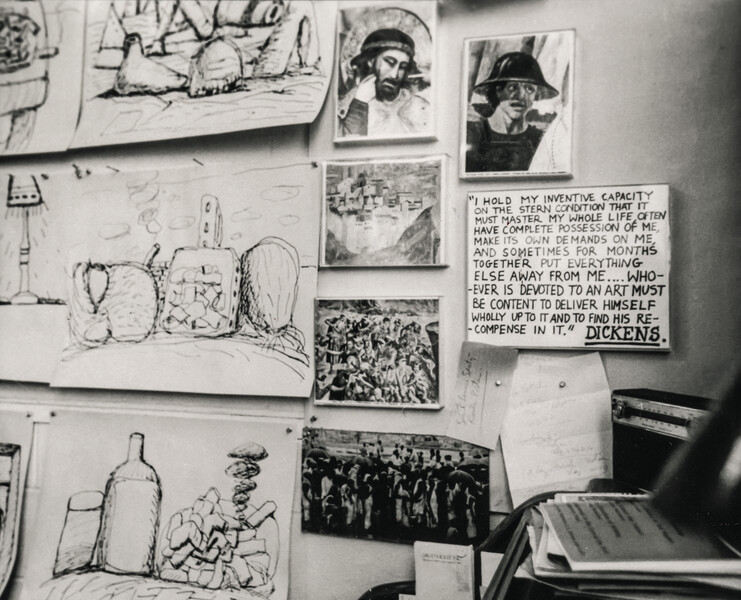

Studio wall with Charles Dickens quote, 1975. Photo: Denise Hare

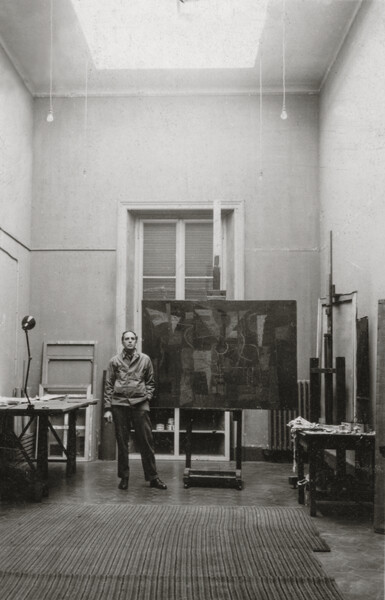

In his studio at the American Academy in Rome, 1948. Photo: Herman Cherry

Dissatisfied with the conventionality of the work that had brought him early success, my father had first sought renewal in Italy at another critical juncture in his life as a painter, in 1948. At thirty-five, he’d already had a notable career as a figurative painter, first as an acclaimed muralist for the Works Progress Administration, then winning a Carnegie Prize for a portrait he repudiated as being ‘too literal’ in a 1946 LIFE Magazine article that included a darkly handsome photo of him in front of a painting he subsequently destroyed. A Guggenheim Fellowship brought further financial support, allowing him to leave a teaching position at Washington University in Saint Louis. For my father success felt somehow suspect, carrying a risk of compromise. But he welcomed the Prix de Rome (a yearlong residency today known as the Rome Prize) from the American Academy in Rome. It offered him an opportunity to see the great works of the Italian masters that he loved firsthand.

He spent that year looking at and absorbing the work of the great painters he’d longed to see, traveling also to Spain and France. Apparently, he destroyed the painting pictured in his Academy studio and brought back only a few drawings on his return home from Ischia, an island in the Bay of Naples where he’d gone to ‘escape the oppression of the masters,’ he later said. In a slide talk at Yale in 1974, he spoke about the drawing he’d kept: ‘It’s a drawing of the town, just looking at the complex of the town. Little white buildings and black windows, done with just a reed I found on the beach, with my bottle of ink. It’s strange how some- thing done offhand like this can lead to painting, you know, like a seed. This led me into a whole period of painting, all through the early fifties.’[8] My parents were to travel twice more to Italy, the next time in 1960, taking me with them following my high-school graduation, for an unforgettable ‘grand tour’ of Italian painting the summer before I went away to college.

Pantheon, 1973 © The Estate of Philip Guston

We began in Venice. With painters Hans Hofmann and Franz Kline, and sculptor Theodore Roszak, thirteen of my father’s paintings of the 1950s had been selected to represent the United States at the thirtieth Biennale. It was another decisive honor for an artist often derided as coming late to abstraction. It was that same year, 1960, that my father first publicly voiced his often-quoted misgivings about abstract painting in a panel discussion with contemporaries Robert Motherwell, Ad Reinhardt, and Jack Tworkov, moderated by Harold Rosenberg: ‘There is something ridiculous and miserly in the myth that we inherit from abstract art: That painting is autonomous, pure and for itself, and therefore we habitually analyze its ingredients and define its limits. But painting is ‘impure.’ It is the adjustment of ‘impurities’ which forces painting’s continuity.’[9]

Untitled (Foot on Wall—Roma), 1971 © The Estate of Philip Guston

Untitled (Rome), 1971 © The Estate of Philip Guston

Eighteen years later, in 1978, he offered this succinct but unsparing characterization of the art world of the 1970s: ‘Regarding the general situation in art today... I haven’t really too much to say. It has become official obviously; it is so insured against failure, against bad painting, against risking. But something must be wrong somewhere, because there is this overwhelming success and at the same time such an overwhelming apathy.’[10] Two anecdotes he told convey a sense of the officialdom of critically approved abstraction: ‘At the first exhibition of Barnett Newman’s paintings, de Kooning was in the gallery. We left together in total silence, down the elevator and through to the street. More silence. Then after a coffee, he said, ‘Well, now we don’t have to think about that anymore.’’[11]

In the run-up to the Marlborough exhibition, my father offered a preview of his work to the then editor of Art News: ‘Before they were shown at Marlborough, Tom Hess... heard something was up, so we went over to the warehouse to see them. He looked at this painting here, one with a piece of lumber with nails sticking out, and he said, ‘What’s that, a typewriter?’ I said, ‘For Christ’s sakes, Tom, if this were eleven feet of one color, with one band running down on the end, you wouldn’t ask me what it was.’ I said, ‘Don’t you know a two-by-four with red nails?’’[12]

The above text is an excerpt from the publication ‘Resilience: Philip Guston in 1971,’ published on the occasion of an exhibition of the artist’s works from 1971 at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles in 2019. Authored by Musa Mayer, Guston’s daughter, the publication offers an intimate view of her father’s state of mind during 1971—a year defined by the artist’s stalwart resilience and creative reinvention.

Explore ‘Philip Guston. What Endures,’ an online exhibition that responds directly to our present moment of overwhelming uncertainty by reflecting upon pain, endurance, and, ultimately, hope for the future. The exhibition includes thirteen important paintings made between 1971 and 1976, a time of social and political turmoil in the United States with parallels to the current state of crisis in America and the world at large.

[1] Hara Estroff Marano, ‘The Art of Resilience,’ Psychology Today, May 1, 2003, https:// www.psychologytoday.com/us/articles/200305 /the-art-resilience.[2] For ‘clumsy’ see Hilton Kramer, ‘A Mandarin Pretending to Be a Stumblebum,’ The New York Times, October 25, 1970, https://www.nytimes .com/1970/10/25/archives/a-mandarin-pretending -to-be-a-stumblebum.html. For ‘embarrassing’ see Musa Mayer, Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston (Munich and Berlin: Sieveking Verlag with Hauser & Wirth, 2016), 218. For ‘simple- mindedness’ and ‘an exercise in radical chic’ see Edgar J. Driscoll Jr., ‘Guston Tries New Approach: Art/Reality via ‘Krazy Kat,’’ Boston Sunday Globe, November 22, 1970. Robert Hughes incor- rectly quotes Kramer as having said ‘an exercise in radical chic’ (Driscoll was the one who said it), and he also used the word ‘clumsy’; see Robert Hughes, ‘Ku Klux Komix,’ TIME, November 9, 1970, 62, https://content.time.com/time/magazine/article /0,9171,943281,00.html.[3] Peter Schjeldahl, ‘The Junkman’s Son: A Philip Guston Retrospective,’ The New Yorker, October 26, 2003, https://www.newyorker.com /magazine/2003/11/03/the-junkmans-son.[4] Hughes, ‘Ku Klux Komix.’[5] Philip Guston, as quoted in Jan Butterfield, ‘Philip Guston—A Very Anxious Fix,’ Images and Issues (Summer 1980).[6] Philip Guston to Bill Berkson, October 19, 1970, Bill Berkson Papers, Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut.[7] See ‘Talk at Yale Summer School of Music and Art’ (1972), in Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations, 150–61, here 161.[8] See ‘On Drawing’ (1974), in Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations, 253–68, here 254.[9] See ‘From Panel at the Philadelphia Museum School of Art’ (1960) in Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations, 29–31, here 31.[10] See ‘Talk at ‘Art/Not Art?’ Conference’ (1978), in Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations, 279.[11] Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations, 279.[12] Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations, 282.