Conversations, Films

Larry Bell: Still Standing

A new exhibition in New York charts the seminal moment in Bell’s practice where he began to radically deconstruct his signature glass cubes into the more architecturally-scaled ‘standing walls.’

The standing walls didn’t only challenge perceptual boundaries; they dissolved them. In so doing, they formed a critical part of Bell’s contribution to the history of Minimalism and installation art.

The Light and Space Movement was formed by a loosely affiliated group of West Coast artists in the 1960s and 1970s. It featured stripped-down works that used geometry and light to create perceptual experiences for the viewer. The movement, which included figures like John McCracken and Robert Irwin, emerged in dialogue with Minimalism at large but was colored by West Coast influences: the feeling of California’s wide-open spaces bathed in light, as well as the region’s history of en plein air painting. Light and Space works were often characterized by performative or immersive elements and employed industrial materials like glass and plastic to explore light. Larry Bell, whose oeuvre spans painting, sculpture, and works on paper, rose to prominence as a leading member of the Light and Space Movement. Bell began to work with glass in 1959, when he was twenty years old – well before the movement was even named.

Bell was one of several major artists in Los Angeles to take up glass at the time, but others quickly abandoned the practice because of the difficulty and danger that it posed as a material. Bell was interested in experimenting with the unique material qualities of glass that shaped viewers’ perceptions of light and space. ‘Even though we tend to think of glass as a window, it is a solid liquid that has at once three distinctive qualities: it reflects light, it absorbs light, and it transmits light all at the same time,’ he said. ‘I like to play around with those things, alter them slightly... and it changes the rest of them.’ [1] Bell realized that by coating the glass in certain ways, he could alter how absorbent, transmissive, or reflective it appeared. He taught himself the complex process of using a vacuum-coating machine, a new thermal evaporation technology developed for cutting-edge aeronautics and optics, to deposit films of vaporized metallic and nonmetallic substances onto panes of glass without altering the fundamental nature of the glass. The process was extremely precise, and the layers were measurable within millionths of an inch.

‘That’s exactly what I wanted to do, to have that feeling of making it important. If someone stuck their head into one of the cubes, they would find an endless variety of relationships between the right angles. But you’d have to get your head inside, and that meant that you couldn’t do it. Opening them up allowed you to go in.’—Larry Bell

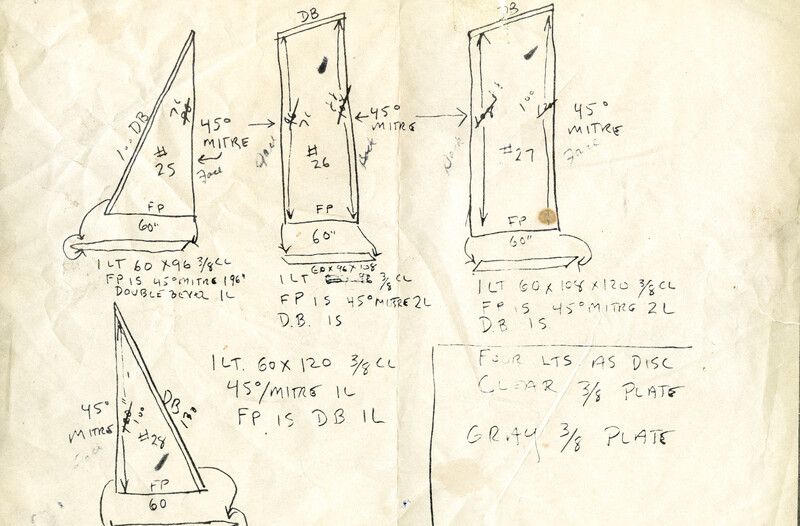

Drawings for The Iceberg and Its Shadow, 1975 © Larry Bell Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

In his early work with glass, Bell made small cubic structures, often in a chrome frame or atop a pedestal. In 1968, he abandoned the use of metal frames in his cubes. Without the constraints of the frame, he could work on a larger scale. Bell began to realize that the corners of the cubes – the right angles where the planes met, making a cube a cube – were where the most compelling light play took place. He had already begun to feel boxed in by the format of the small cube and its tight containment of space. That same year, Bell embarked upon the architecturally scaled ‘standing walls.’

The standing walls were large, open, freestanding glass panels connected to one another at right angles with silicone rubber and configured into corners, squares, and zigzags in site-specific arrangements. Rather than being contained or constrained, the standing walls were wholly permeable to their environments, creating space that viewers could walk through. Of the standing walls, Bell said: ‘By taking this ‘window’ out of [the] context of being in a wall to separate things, and putting it in the center of a room as a sculpture, another kind of credible tension exists in the piece. It’s an improbable tension, and my work’s always been about that kind of stuff.’ [2]

Larry Bell, 'Iceberg', 2020, Cornflower Blue, Spa, Blush, and Lagoon laminated glass, Dimensions variable © Larry Bell Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Bell’s standing walls have been described as a ‘contemporary take on Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man,’ as he scaled them according to ‘the breadth of his reach, the height of his jump, and a weight he can manage to lift with the help of one other person.’ [3] Due to the grand scale of the standing walls, galleries were baffled as to how to exhibit them. Committed to his project, Bell broke with gallery representation and moved from Venice Beach, California to Taos, New Mexico where he had room to experiment and grow. The earliest standing walls were clear and uncoated, as Bell’s vacuum-coating machine could only accommodate 20-inch panes of glass. However, in 1969, he graduated to a new machine that could apply thin coatings to panels of up to six-by-ten feet, including the standing walls.

The standing walls didn’t only challenge perceptual boundaries; they dissolved them. The environments that they created were spatially ambiguous. Depending on several factors – where one stood, the time of day – the glass could be hard or atmospheric, reflective or translucent, material or immaterial, or light- filled or shadowed, with endlessly shifting colors. On a literal level, the arrangement of the standing walls was also prone to change.Bell made the composition of the panels site- specific to every space in which they were installed to ensure the desired interaction between the glass and the space, which was affected by the measurements of the space, the location of windows and amount of available light, and the ways in which visitors might flow through the space. Bell has referred to the standing walls as ‘improvisations,’ able to be configured in endless combinations – in stark contrast to many large-scale sculptures, public and otherwise, made at the time.

Larry Bell with the Iceberg and Its Shadow, taken at Washington University in St. Louis in 1976 © Larry Bell Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Photo: Larry Bell

Larry Bell, 'Iceberg', 2019, Grey glass and Optimum White, True Sea Salt, and True Fog laminated glass, Dimensions variable © Larry Bell Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Photo: Genevieve Hanson

The standing walls were first exhibited in ‘Los Angeles 6’, a group show at the Vancouver Art Gallery in British Columbia in the spring of 1968; two years later, they were exhibited at the Tate Gallery in London. These installations quickly rose to acclaim as they attracted institutional exhibitions. Among the most widely known of the standing walls is ‘The Iceberg and Its Shadow’ (1974). The sweeping work, which took six months to fabricate, consisted of 56 large-scale, freestanding, two-sided glass panels in various heights and shapes. They were grouped into a section of clear glass panels (‘the iceberg’) and a section of dark grey glass panels (‘the shadow’) and coated with an opalescent nickel chrome alloy and silicon monoxide. The installation comprised about 6,000 square feet of coated glass in total. In addition to its ability to change endlessly in response to ambient light conditions and the viewer’s perspective, ‘The Iceberg and Its Shadow’ could be arranged into a factor of 56 possible configurations; the viewer, Bell pointed out, could only see the ‘tip of the iceberg.’ [4] The work was shown in Fort Worth, Texas in 1975, and would go on to join the collection at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1977 after being donated by prominent collectors Albert and Vera List. Bell had two conditions for the work: the 56 panels had to stay together as a unit, and he had to be allowed to set it up himself on site, as the installation was so intertwined with its environment. MIT allowed the artist three years to rearrange ‘The Iceberg and Its Shadow’ in various ways in different areas of the campus. While installing at MIT, Bell met the scientist who invented the strobe, Dr. Harold Edgerton. The artist’s interactions with Dr. Edgerton at this time laid the groundwork for the important waterfall piece ‘Hydrolux’ that would follow years later in 1986.

The standing walls form a critical part of Bell’s contribution to the history of Minimalism and installation art. They set an important precedent for work that would follow, perhaps most significantly the ‘nesting box’ works – open cubes without top or bottom panels – that form a central part of Bell’s practice today, an exemplar of which is ‘Pacific Red II’ (2016 – 2017), a set of six nested boxes that were on display at the 2017 Whitney Biennial. With the invention and subsequent development of the standing walls, Bell broke with the cube and found a way to work on a grand, ambitious scale. The immersive environments created by the standing walls were capable of challenging perception in new and exciting ways, their expansive openness opening viewers up to other ways of seeing.

– [1] Larry Bell quoted in Robin Clark (ed.), ‘Larry Bell,’ New York NY: Rizzoli Electa, 2018, p. 11. [2] Ibid., p. 13. [3] Ibid., p. 13. [4] Larry Bell in conversation with Cliff Lauson in Ibid., p. 215.

–

‘Larry Bell. Still Standing’, is on view at Hauser & Wirth New York 22nd Street 20 February – 11 April 2020.