Books

Exploring the Archive: Pipilotti Rist on Nam June Paik

With a glimpse into the exhibition taking over an empty industrial space in Zurich, the glossy dustcover of ‘Nam June Paik: Jardin Illuminé’ provides a luminous invitation into one of Hauser & Wirth’s first self-published books. Produced following Paik’s 1993 exhibition, the book has a silken hardcover, with a debossed title and red foil-blocked spine.

Installation views of the extensive exhibition come to life on a thick paper stock, recreating the energetic show with neon components. The book features numerous portraits of the artist, as well as video stills, some of which portray frequent collaborator and cellist Charlotte Moorman with ‘TV Bra for Living Sculpture’. The publication opens with a poetic introduction by Pipilotti Rist, which is excerpted below and chronicles a definitive moment in video art’s evolution through a characteristically imaginative and whimsical narrative.

Installation view, ‘Nam June Paik: Jardin Illuminé’, Galerie Hauser & Wirth, 1993

Galerie Hauser & Wirth, ‘Nam June Paik: Jardin Illuminé’, Hardturmstrasse 127, Zurich, 1993

Here is the Korean bed of moss over there ist Mount Harakiri there the nail file factory further right the American bungalow snow climbs up the pane some parents’ home or other there is the frozen lake In the twilight I fly through a street with my backpack propeller at a height of 25 meters. I can see into all the houses. Here four people sit down to eat. There a child crawls on a red carpet. Further left three adults discuss the arrangement of pictures in a catalogue. There two kiss under a bluish light. There someone tinkers on a model ship. Most have the television running. I quicken my flight. Sweet Mister Paik is seated behind me on the luggage rack. Our eyes are a blood-fueled camera. Once more we are enthused by multifarious life. We digest impressions directly, or, at a pinch, register them on magnetic tape. I behold our organic muddy world and simultaneously remember, way back in the part of the brain for my right visual field, the strange design our neighbour’s former television set had and the tree between our houses. It is funny; everyone has neighbours and everyone remembers their television sets and their backyards.

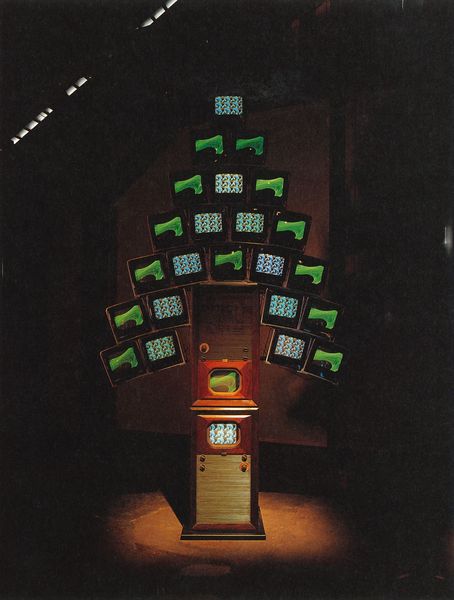

Nam June Paik, Tannenbaum Tree, 1992 © The Estate of Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik, Versaille Fountaine, 1992 © The Estate of Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik has eaten every video innovation. He has no fear of machines; machines are basically stupid. Over the decades he has lept full force into the cornucopia of video technology.

Nam June Paik is a wild dog. He sees a tree, pees on it and the tree lights up. The leaves become monitor screens that gleam and flicker bewitchingly. He feeds them rhythmic picture sequences from the player; this is the chlorophyll dissolved in water. The electric cables, which no one but him can toss around so artfully, are the roots. As long as no one switches off the power, no problems arise. Those who wander along under the trees and bushes need only (be able to) surrender to the flood of cathode rays. Their retinas are massaged by fluorescent rain. Their own nervousness suddenly appears to be comparatively minor. The garden’s seasons change in mini-seconds. This is the way you prolong life. Salvation lies in repetition! We buy ourselves a kilogram of apples. Nam June Paik has eaten every video innovation. He has no fear of machines; machines are basically stupid. Over the decades he has lept full force into the cornucopia of video technology. Now he is the great Renaissance artist of video art with his twenty-seven trained assistants.

In the beginning he flitted around the world with the first portable video equipment. He was a merry Fluxus artist and coaxed strange tones out of the world. On b/w documentary photos he works with an innocent, child-like, earnest smile. One just has to kiss him. Because of the nostalgia-laden era, he is sentimentally blessed and can get away with anything. He plays on video keyboards or with digital effects on a ‘color piano’ (Paul Klee’s dream). Without any respect for technology he rides into the sun. This is cool, which makes him the role model for the video girls. He is our media grandpapa who can do everything. Sometimes video history, as short as it is and supposedly unencumbered, seems under threat of being trampled by his over-sized shoes. With his video installations he has monopolized a giant area of formal potentialities on the theme of ‘the box with life in it’ for decades by exhausting virginal variations on ‘the screen, the poetic lamp.’ The others and the new video artists must smother, must capitulate, or bypass him via content. Isn’t this healthy?

Video is the synthesis of music, language, painting, movement, mangy mean pictures, time, sexuality, lighting, hectic action, and technology.

Paik’s new hardware battles remain just as imposing as ever because, as far as energetics goes, he does not allow them to slip from his small fine hands. A video artist keeps account of about 54 video cables, Paik a great deal more. We quietly fly on through the cabled suburbs. The world in front of, in back of, or between the window and TV panes is the biggest video installation we can ever imagine. It is all a question of your standpoint. Video is the synthesis of music, language, painting, movement, mangy mean pictures, time, sexuality, lighting, hectic action, and technology. This is fortunate for the TV spectators and the video artists. They love video, they love it with all its disadvantages, e.g., the poor resolution because of a reduction from 560 x 720 dots. Even because of it. It kick-starts our phantasy and, behind our eyeballs, turns into an orgy of sensation and imagination. The monitor is the glowing easel where pictures are painted on the glass from behind.

Nam June Paik, Flower Tree, 1992 © The Estate of Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik, Rocketship to Virtual Venus, 1991 © The Estate of Nam June Paik

The screen is a magic lamp. The machine throws pictures at us that we recognize from behind our eyelids: pictures from our unconscious when, for instance, we are half awake, euphoric, nostalgic, or nervous. By means of formal manipulation (color staining, digital distortion, layered perforation) and of hyper-speed, we lure the subconscious out of the machines and hold up its mirror to our own subconscious. We now change places. Mister Paik takes over the steering wheel and I take my seat on the luggage rack. Soon it is dark. Turn on the power: Fear is a butcher I am a reptile Come, bountiful spirit, impregnate me Nature gave me hands I give them back to her Come, bountiful spirit, impregnate me.

Since its founding in 1992, Hauser & Wirth Publishers has been devoted to the presentation of unique, object-like books and a rich exchange of ideas between artists and scholars. Exploring the Archive continues this commitment through the digitization of excerpts from seminal, rare, or out-of-print titles from the Hauser & Wirth Publishers archive, which comprises monographs, artists’ books, exhibition catalog, and collections of artists’ writings. This essay was translated from German by Jeanne Haunschild in 1993. ‘Nam June Paik’ is on view at Tate Modern, 17 October 2019 – 9 February 2020.