Essays

A Soliloquy: Phyllida Barlow on David Smith

David Smith working on ‘The Banquet’ in 1951 at Bolton Landing. Photograph: the artist © 2019 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Tracing fragments of sculptural experience, Phyllida Barlow responds to the work of one of the foremost artists of the 20th-century, David Smith. Barlow’s own making process falls in and out of dialogue with David Smith's ‘The Letter’ and ‘The Sitting Printer’ in this uniquely personal soliloquy, commissioned by Yorkshire Sculpture Park for the publication ‘David Smith: Sculpture 1932-1965’, coinciding with their major retrospective of his work.

Whether it is the manipulation of material or the impulse to make and connect with objects, Barlow suggests that ‘sculpture is the most anthropological of the artforms.’ Opening at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, ‘David Smith. Field Work’ will further explore Smith’s diverse visual language and multifaceted creative process.

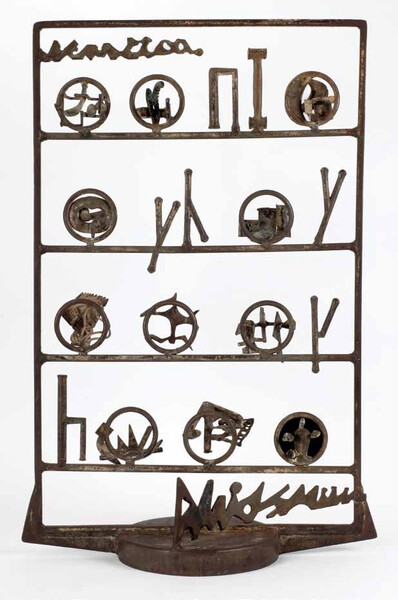

– I am writing about David Smith’s sculpture. I write about what I remember – Not about facts, figures, dates, history, why, when, where, what, how – I will speculate, I will adapt what I remember, Seeking the experience, Trying to nail it, To what it was that has remained – Sentient, visceral, luscious, nostalgic; Full of longing, As if there is a death. Maybe 1963? Maybe the Tate? I am standing one side of The Letter… I am looking through the rows of hieroglyphic shapes; I try to make it solid, filling in the gaps between the shapes; I am uncomfortable; I cannot make it become a whole; It escapes, becoming transparent; The room beyond devours; The hieroglyphics are dancing unevenly into the space beyond; Passers-by are colliding and interrupting the steel boundary and the horizontal bars; The hieroglyphics flicker with balletic grace – captured and stilled; I don’t yet know that sculpture can defy its own language; That this is both solid and full of air; That the space it owns is endless; That this isn’t an image – fixed – But it is an image which constantly un-fixes; I am walking around it; It becomes a slice, edge on; Nodules and lumps and bumps bulge out of the frame; It is another work; A conjuring trick; A flattened upright grid-like structure has compressed itself into a column; Then round to the other side and the flattened grid with its dancing hieroglyphics reclaims its place –Sieving the space; letting the world beyond itself come and go – Its transparency controlling all within its realm.

David Smith, The Letter, 1950 © 2019 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Art Resources

David Smith, Untitled, 1958-1959 © 2019 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Christopher Burke Studio

(1963: I am in my (art school) space outside but in the basement; I build a timber frame, then another one; I join them together with horizontal timber strips about 10" long; I cover the structure with chicken wire; I smother the chicken wire with plaster-soaked scrim; It is a white, solid wall. I make a series of turret shapes; I have been looking at Indian sculpture and architecture; I like the decoration that enhances and defies the curvaceous forms; I am decorating the plaster walls with swirls and circles and ‘S’-shaped reliefs; I am told that proper sculpture has nothing to do with decoration; But I am remaking The Letter, which I stood beside yesterday; I am remaking it as it should be; I am solidifying the air; I add the turrets onto the top edge of the wall; I have made a two-sided sculpture; I am intrigued by what I have done But it has nothing to do with The Letter; I have not made air solid; I have not made transparency; I have not made flickering movement become stilled; I have not made space active and vibrant and devouring; I have not made the world around enter and collide with the structure; I have not let anything in, and then witness its escape; I am in thrall of The Letter; I am discovering the anomalies and contradictions, the paradoxes and oxymora Which sculpture so defiantly uses, And as such, repudiates definition, Embracing so much which is not sculpture into its realm; Sculpture is sculpture’s worst enemy; There is a vast territory, a no-man’s land, Where sculpture is as much about painting, theatre, film, performance, as it is about sculpture.) I am returning to stand beside The Letter; The air, the transparency, the weight, the soft flex, the edge, This osmosis between its space within and its space beyond –How can that ever be emulated? I want it to be mine; I want to be the only person who knows it; I am jealous of it; I am duped and tricked; I have been thinking that sculpture was this But now it is that… And I know nothing. Much later, maybe it’s the 1980s or early 1990s – and I don’t know where. Maybe a gallery or a museum, but the place has dissolved. Only the object, the sculpture, remains, locked into my mind.

David Smith, Rebecca Circle, 1961 © 2019 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson

Is it a sculpture? Only as much as the word ‘sculpture’ distinguishes one kind of object from other objects – those other objects in the world around us that can be defined by their use… domestic, functional, everyday, public, expedient. This sculpture is a hybrid: neither useful nor useless. The initial encounter announces an object that is a trolley: familiar, heavy and purposeful. It is an object parked more than displayed, waiting to move on. Its familiarity is deceptive because it is anything but familiar; if it is a trolley, then how can its skeletal structure serve any purpose? And, as its title claims, how can it be a wagon? Is it some abandoned rail-track equipment, now defunct and stripped down to its bare elements? The curved armature, an axel, is expedient in how it joins the front and rear, grabbing the arched wheel axles with functional simplicity, the front part wrapping itself around the steel bar with a tight grip, the rear bolted on uncompromisingly to the arched wheel support. The wheels themselves are solid discs, toy-like in design but anything but in their weight and form; in fact more like weightlifters’ dumbbells. There is a freak wheel at the rear left, it being three or four times the size of the others; as such it translates as having a specific purpose. But what? Its idiosyncrasy begs questions but none that can be answered.

‘Yes, it is a sculpture, and as such it has the freedom to be singular, different, awkward, beautiful and gloriously without explanation.’

And so it stands its ground: its four wheels unyielding, steadfast on their spot; but the double-kinked forged steel stump, heavily welded to the axle, hewn and fettled, a raw dead-weight, stands erect and phallic, pert and awake in the middle of the horizontal axle; there is a determination that this is its place; this is not cargo to be carried by this wheeled structure; and it’s not a balancing act, although it could seem like that, but a contradiction: its posture is alert and expectant, ready to move despite its perpetual stillness; it pins the object to where it is but speaks of an unpredictable and urgent force that could release movement at any time. As such, it is the compass needle to why and what this indefinable object is, and where it might be going. Despite its title – Wagon II – it is potently unnameable. But this nameless, indefinable object is bespoke – irrefutable, stubborn and perfect, refusing to answer to what it is; it cannot be argued with; and it waits with a dangerous patience. Its magnificent authority could survive anywhere – it is self-sufficient, confident in its oddness and its enigma. Every act of production is exposed; nothing is hidden; the lean, fleshless structure commands the space it holds. Who would dare to typecast it, or compare it to something we might think it is like? Yes, it is a sculpture, and as such it has the freedom to be singular, different, awkward, beautiful and gloriously without explanation.

David Smith, The Sitting Printer, 1954-55 at Bolton Landing Dock, Lake George, New York © 2019 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: the artist

David Smith, Wagon II, 1964 at Bolton Landing, c. 1950 © 2019 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: the artist

It’s November, 2018, and a cold day, contradicted by the bright autumn yellows and reds. We’ve come to Storm King. At the brow of a tree-lined hill is a group of David Smith sculptures. Momentarily, they are camouflaged – their muted greys, blacks and patinated greens indistinguishable from their autumnal environment. The Sitting Printer is the first to emerge. I think of Duchamp – the bicycle wheel on the stool, and the stool appropriated as a plinth by both artists. And how much I dislike the ‘appropriation’. And how Duchamp has claimed the intellectual high ground because of the readymade, the objet trouvé, the found object… and its current legacy, which has morphed into eBay as the readymade resource for anything and everything. And the impact this is having ‘making’. No doubt, it is positive, but not necessarily so. Arrangement as display can be a dull replacement to the awkwardness which fixing disparate elements together demands. I marvel at the awkwardness of The Sitting Printer – the blatant contradictions of its stacked-up bronze cast found objects – stool supporting the printer’s type case, itself supporting the top components of circular dish attached to a deceiving neck and shoulders – deceptive because from the side these uppermost parts are robust and broad, but from the front they become slender and fragile, whilst the rectangular printer’s tray is a mere slice from the side and broad from the front and back. The forms twist counter to each other. For me, it shares similar formal inventions as The Letter and Wagon II. And with that I have this sense of how deeply rooted a sculptural language can be initiated. I think about Louise Nevelson and her obsessive hoarding and stacking, the thunderous presence of Black Wall, where her tireless ‘appropriating’ and use of readymades, or found objects, transcends what Duchamp achieved, mutating her materials into malleable stuff which buries the origins of these found objects into energetic formal concerns, pushing the work into dangerous territories of courting ugliness and clumsiness, and an abuse and re-invention of craft, all delivered with an urgency to bring into the world a new entity, fearless and brave. And how this fearlessness, this commitment to the object as different, maybe at the expense of a conventional idea of beauty, is what I have connected to through my 50-year relationship with the sculpture of David Smith.

‘The sculpture of David Smith will always fulfil... promise – always surprising us with endless contradictions, embracing ugliness and courting beauty, manipulating labour into a lightness of touch’

David Smith, Untitled (Study for Agricola I), 1951 © 2019 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

But the David Smith sculptures are beautiful, elegant and superbly crafted. Looking at Picasso’s sculpture, at González and Zadkine and Richier, at Wotruba and Hepworth, and Stahly and Étienne Martin, and Noguchi and Lipchitz… what is it about these mid-20th century artists (sculptors)? Although a lot of my experience at art school was inspired by and promoted adventurous approaches to making sculpture, it was also disciplined: sculpture was taught through learning specific techniques – casting, welding, carving, construction – and with these techniques came many other processes with materials – clay, plaster, wax, ciment fondu, sheet materials of ply and metal, which in turn led to the use of fabric, paper, papier-mâché, sand, resin, earth, and much more besides. However, I was not good at most of the techniques that were expected to be learnt and to which great importance was attached. It was humiliating to be incompetent at acquiring these skills, but it instilled in me a defiance and a determination. It also encouraged awe for the works of the aforementioned artists, not least the sculpture of David Smith. Inevitably, during the early 1960s, I turned against these artists, but not David Smith, Richier, Nevelson and Picasso. They have remained consistent reminders of the courage that the contentious, difficult artform of sculpture demands, where the quest for a sculptural language is more demanding than a belief in sculpture as a definable art form. And now I browse the works of those artists I rejected so vehemently in the 60s, marvelling at the brutal formal language, the excessive emotion, the contrary forms, restless and unresolved, the lumpen qualities, the solidity, and the open, fretwork structures… each claiming this hope for a sculptural language which transcends the great skills, crafts, knowledge and experimentations of making, presenting instead the remarkable conviction of new forms, distinct and separated from the world around, but reflecting everything about that world – an unknown form, resilient, defiant and contentious, to reciprocate all that is known. The sculpture of David Smith will always fulfil that promise – always surprising us with endless contradictions, embracing ugliness and courting beauty, manipulating labour into a lightness of touch, surprising us with dangerous alchemies of weight and weightlessness, partnering with painting and drawing to solidify line and mass, and persistently refuting sculpture only then to reclaim it. –

‘David Smith: Sculpture 1932-1965’ is on view at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, 22 June 2019 – 5 January 2020.

Curated by the artist’s daughters Rebecca and Candida Smith, co-presidents of the David Smith Estate, the exhibition ‘David Smith. Field Work’ will situate itself between the drawn image and sculpted form, and is on view at Hauser & Wirth Somerset from 28 September 2019 – 5 January 2020.