Conversations

In Conversation with Mark Bradford

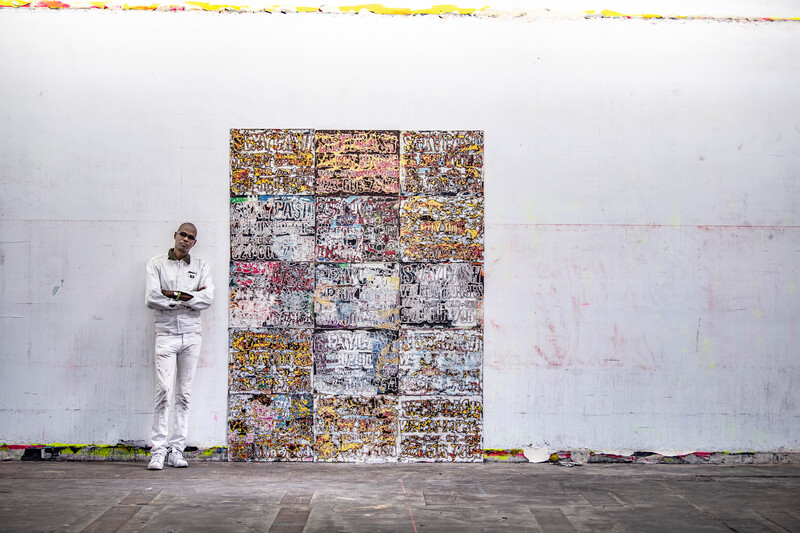

Mark Bradford in his Los Angeles studio, 2019. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

W. Tate Dougherty, Senior Director, has worked intensively with Mark Bradford since Mark joined the gallery in 2014. They have built a close dialogue that emerges here in a discussion about preparations for Mark’s major exhibition at the Long Museum in Shanghai this summer.

Mark Bradford: How many questions?

W. Tate Dougherty: Twelve.

MB: Like the apostles.

WTD: I made sure it’s not thirteen. Sometimes I call you Marco Polo. This is not only because we have spent a fair amount of time in Venice, but also because you have loved to travel since you were a boy and you have always been especially interested in other places and people. The Long Museum show is your second major exhibition in Shanghai. What inspires you about the city and what’s it like to make this exhibition in that context?

MB: Well for me, Shanghai is becoming more familiar now, but it really felt ‘other’ when I first got there. It was all kind of part of a fantasy and imagination. It was really an imaginary landscape for me, because everything looked abstract to me. The language on everything looks like big abstract paintings because I can’t read anything. So I’m constantly looking up at these big fields of abstract paintings, which is kind of fascinating to me. I’ve always thought that people think that abstract paintings are completely devoid of ‘meaning,’ but I never thought that that was the case. And when you’re looking at a sign at an airport... and it’s completely abstract to me, but you know it has meaning.

WTD: To somebody!

MB: I just have to figure it out. Somebody just has to interpret it. That’s always fascinated me. I like the idea of something that actually functions outside of the West, with their whole history backing it. I liked the idea that Shanghai was once a colonial city and very much had these roots and kind of ‘Europeanness,’ but they also kept their own traditions. Like you said, Marco Polo was one of the first people to go to the East.

WTD: Several times!

MB: At the time, they called it the ‘silk trade.’ I just like to go to new places, discover new ideas.

WTD: What is one of your favorite things about Shanghai?

Mark Bradford in his Los Angeles studio, 2019. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

MB: Getting lost and having to navigate with your senses because you can’t read anything. So stopping and asking people, and pointing and using pantomime, and trying to express yourself without the support of logos, of the written word. That’s interesting. The whole thing feels in some ways like ‘Blade Runner’, you know.

WTD: Which appears...

MB: Which appears actually in the Pull Painting; I used the billboard advertisements from ‘Blade Runner’. Now, I didn’t plan it that way. I just happened to be looking through all the stacks and the stuff I pulled in from the streets and there it was. The colors worked, the shapes worked, and ‘Blade Runner’ appeared.

WTD: And it’s going to Shanghai.

MB: And it’s going to Shanghai.

WTD: ‘Los Angeles’ is such a perfect Mark Bradford exhibition title. It’s hard to believe you haven’t used it before. Tell us more about Los Angeles as an exhibition, specifically what it means to show ‘Los Angeles’ in Shanghai. I guess ‘Blade Runner’ is one answer to that.

MB: It’s ‘Blade Runner’. And also it’s the multiplicity of worlds that are occupying the same space and rotating with each other—around each other—at the same time. Sometimes they’re little worlds. Sometimes they’re bigger worlds, but they’re orbiting around each other. Sometimes they cross with each other, sometimes they don’t at all. And to me, that’s because there’s a horizontalness to Los Angeles that makes the kind of lunar possibility that floats on top. It’s not like New York where everything is vertical, where you understand it kind of goes up to the heavens. I always see Los Angeles as being horizontal, and just like early explorers thought that if you kept going in the ocean, you would fall off the ends of the earth, I see Los Angeles like that. It’s so stretched out that if you keep going in either direction you’ll fall off the edge of the earth. So Los Angeles for me is multiplicity of everything—of cultures, of freeways, of languages, of a horizontalness that’s not all the same. You can be on the west side of town and the horizontal—when you’re driving the feel of that asphalt under the wheel is very different than when you’re in the southeast part of the town or in the poor part of town where you can feel the pockmarks. So the relationship is different when you’re driving, you can almost tell what part of the city you’re in based on how many pockmarks there are.

Mark Bradford Studio, 2019. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

Mark Bradford Studio, 2019. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

WTD: Who’s paying the taxes.

MB: Who’s paying the taxes.

WTD: And the most defining feature of ‘Pull Painting’ is horizontality. That’s the ‘Blade Runner’.

MB: Yes, and that’s always been the thing. I’ve always been fascinated by landscape painting: these big Old Master landscapes, Winslow Homer; I think I lived with a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy.

WTD: And all the Hudson River painters.

MB: All the Hudson River painters. It’s a place to lay my imagination.

WTD: Which is kind of the American Dream anyway.

MB: Not urban or ‘urban-ness;’ this kind of ‘urban-ness’ goes up. It has a verticalness. It goes up. I’ve always liked space and horizontalness; and then the horizon line.

WTD: Well, in the tradition of abstract painting, that’s very much where you put yourself, too. I mean you are an American artist. American Art comes out of the great play with the landscape, through abstraction, which became a great play of emotions. And then your insistence on making that social, on making it have bite in the world. So that makes perfect sense to me.

MB: Well, it seems like sometimes they want to say the social belongs to the vertical, the social belongs ‘urban-ness.’ I don’t necessarily think anything belongs to anything. There is a horizontal landscape feel even in the most densely urban environments.

WTD: Let’s look now to ‘Mithra’. It’s one of your most important and iconic works. So much has changed since you made it for Prospect.1 New Orleans in 2008. What’s it like to see it again now?

MB: It was interesting, because when I was opening the boxes and the original panels were still there, you could smell New Orleans, the lower ninth ward of that particular time, and it brought back all the memories of that particular time because it has changed. It has been renovated and a lot of that history has been kind of lost. So I never thought about smell before in a work of art and I realized, ‘Oh, this actually is going to have a very particular smell to it because it was really dried and baked in the sun of the lower ninth ward one year after.’

WTD: Absorbing its context.

‘We were the kings of our own world and we were gathering material that would support our bias, and we were firing it off at the next world.’

MB: Absorbing it and the land was still very wet, in a way. I was there maybe a few months after, and the time I started working on the ‘Mithra’, there was still a lot of moisture in the land, moisture in the houses, a lot of mold —it was still kind of a wet feeling. It hadn’t really dried out yet. And a lot of that came right onto the sculpture itself. So smell is something that really brought back that time. Shanghai is a port city, so it does have this idea of water and it also has a tumultuous history around the port. Port cities always have the most tumultuous histories because that’s historically where all the money was. That’s where trade was, that’s where... import; export; my people.

WTD: Trade.

MB: So port cities always have this kind of historical ‘fighting.’ Not fighting, but loaded history, heavy history. You look at the Founding Fathers, the founding countries. New York and every place, there was a port that we could dock, drop off the goods.

WTD: So many great cities were built because of their ports. New York being the case, again, it’s one of the great safe harbors of the world, Shanghai as well. It’s the gateway to the hinterland

MB: So that played into it, the idea of cargo, and trade, and slave trade. It’s all, you know, at one time African-American people were cargo in boats—the bottom of the boat.

WTD: It’s also global for shipping containers.

MB: I was going to say the shipping container is global. Shipping containers are global. It’s what destroyed much of the lower ninth ward when the docks broke: a lot of the damage actually was from the shipping containers, not the water. They would smash these torpedoes into the homes in the lower ninth ward. They were still littered everywhere when I was there.

WTD: Like a war zone.

MB: It was like a battle zone. It was like a war zone.

WTD: Since you’re mentioning globes and destruction, we’re sitting among these beautiful new Globes. It’s going to be an incredible installation there. You’ve been playing with the idea of doing Globes for a long time. From the first time I came to your studio over five years ago, you were thinking about this. So it’s great to see these ideas come to fruition. They relate so much to your earlier work—the Soccer Balls or the Buoys—but this is something new and the scale is larger than ever. So obviously from what you’ve just said, they relate to your thinking of globalism and they have something to do with your Shanghai show. So the question is, could you walk us through when you first started thinking about making Globes and how the idea developed into what we’re seeing now all around us?

MB: It might have been just from reading the newspaper and listening to these constant debates from different sides. This multiplicity of opinions around every single idea is almost like we’re not talking to each other, we’re just rushing to believe whatever information will support our bias. And so that’s what it felt like. It felt like we were all orbiting around each other, but not really talking to each other. We were the kings of our own world and we were gathering material that would support our bias, and we were firing it off at the next world.

WTD: [laughing] Little missiles.

MB: Little missiles back and forth, which are called comments and likes.

WTD: ‘Twits’… ‘Twitters’... ‘Tweets!’

Mark Bradford in his Los Angeles studio, 2019. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

MB: Tweets! You would tweet from your world to the next world. And they would tweet from the next. So that’s really where it came from. At first I thought, I’m going to have all the different solar systems. And then I thought, wait a minute. No. Actually I’m going to have this one, and I’m going to turn this one into a solar system.

WTD: Or one planet, they’re all Planet Earth, right?

MB: Yes.

WTD: So I love these new large-scale black and yellow paintings that are on the wall. They remind me a lot of your famous work at the US Pavilion in Venice, ‘Oracle’. In my mind, they are a bit like Oracle’s children. Are they related in your mind?

MB: They are ‘Oracle’’s children. I was wondering how to make them into that and it was just so spontaneous. In Venice, I was really responding to the architecture and this kind of vaulted ceiling. These are really my walking down the road of Dante’s ‘Inferno’. This is me. This is just a first step of me walking down that road and trying to develop a kind of material language around that story.

WTD: And obviously, the yellows and the burning, the oxidation and the burning of the yellow, and Oracle’s kids relate to the landmasses in all of the Globes. Is the world on fire?

MB: Yes. The world is on fire.

WTD: Indeed it is. This is the most sculptural show of your career so far. It includes ‘Mithra’, the Globes, the largest Waterfall you’ve ever made, and the Buoys. Although they are quite different formally, each relates to different aspects of your painting. Is there a relationship in your mind among the different series of sculptures?

MB: They all come out of painting. The material really comes out of an American-ness to materiality. I mean, you can go back to Rauschenberg and this kind of material. Maybe my idea of painting might go back a little further to the Classics, but they all come out of painting. I don’t know exactly how.

WTD: It really is all an extension from when you attach the soccer balls physically to the paintings. You can almost see that the Globes are attached to, and have a resonance with, let’s call them, ‘Oracle’s children.’ I know you’re going to come up with titles later. Now I’d like to ask you about the smaller paintings you’ve made for this exhibition. They are something we haven’t seen before. How did you make them?

MB: Actually, I struggled with making them individually, and then when I just put them all up as one grid and made them as individual components within a grid, it got easier.

WTD: But the technique is something new...

MB: I would lay down whatever material, or whatever shapes, and then I wanted it to erase it. Like Richter uses the squeegee. So I took all of them, the paint, all of the papers, and put a lot of glue in it. And then I just dumped it on top of each one of them and it dried. So in a way, it’s like when you drop a big splatter of paint on concrete and it just kind of takes over? That’s what I did on each one. To kind of erase it or push it back.

WTD: They’re beautiful. And like I said, we’ve never seen anything like it before. The text paintings are incredible. The language comes from the great song ‘Dancing in the Streets’, which is also the name of the video you’re making for the exhibition. Music has always had an important role in your work. Why are you drawn to this song now?

Mark Bradford in his Los Angeles studio, 2019. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

Mark Bradford Studio, 2019. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

MB: Because it sits between two things. It sits in popular culture and it sits in civil rights, and it also has a lot of mystery and myth around it. The pop music history or the soul history wants to say that this belongs to a wonderful Motown sound but there are also certain things you can’t look away from, such as the timing of the song and how it would move through at a time when African-American people were actually rioting in the streets and protesting their treatment by the hands of the larger population. So I like it because it sits in between myth, reality, stories, and music. It has a mystery to it. We’ll never know.

WTD: And you can dance to it.

MB: It’s a great song to dance to, still.

WTD: People ask me all the time about the titles of your work. None of the new works have been titled, but I know there will be some great ones, and I am guessing you already have some ideas floating around in your head. Please share some of the process of how you title your works.

MB: It’s very organic. Sometimes I start with the title and then I make the work. Sometimes I make the work and then the title. I pull out of the billboard material a piece that has a little language or something that I like on it. Like the ‘Pull Painting’. I could call it ‘Blade Runner.’ I might not, but I might take a little bit of the text from one of the lines in ‘Dancing in the Streets’. There’s one line, it says ‘across the ocean, blue, you and me across the ocean blue.’ I like that. So certain things ring in my head. The Waterfall, the Globes, they just come, and either they come in the beginning or they come at the end.

WTD: I’ve seen other people give you a title. There’ll be describing something and they’ll say, ‘Oh, that’s this or that’ and you’re like, ‘That’s it!’ It just comes out of the universe.

MB: I’ve seen people who were talking about the work, and I’m like, ‘Oh, that’s good.’

WTD: What are you currently reading and what is the last movie you saw?

MB: God, the last movie I saw was Stephen King’s ‘Pet Sematary’.

WTD: [laughing] Okay.

MB: And I am re-reading ‘The Swerve’ and reading ‘Origin’. One is by Stephen Greeneblatt and one by Dan Brown. Go figure that one.

WTD: Sounds very Mark Bradford to me.

Forming the largest exhibition to date of the artist’s work in China, ‘Mark Bradford: Los Angeles’ is on view at the Long Museum in Shanghai from 27 July – 13 October 2019. Bradford has created a new work ‘Waterfall’ responding to the architecture of the museum, which will expand across 12 meters from floor to ceiling. Included from a diverse selection of other recent works are Bradford's new series of large-scale paintings (2018 – 2019), which use material to investigate the civil unrest experienced in 1965 in Los Angeles during the Watts Rebellion. This fall, Bradford will present an exhibition of new works at Hauser & Wirth London entitled ‘Cerberus’. #MarkBradfordInChina