Profiles

The Pathos Collector: An outsider’s mission moves inside

The Keepers

by Cassie Packard

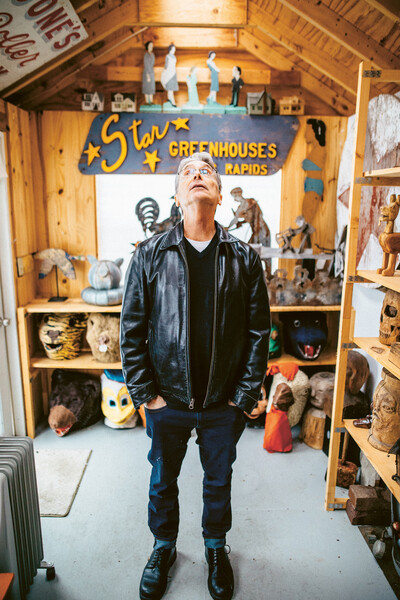

Inside Jim Linderman's home in Grand Haven, Michigan, 2018. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

- 13 April 2019

‘I’ve never really been a postage stamp collector, which is what I call art collectors who need one of each,’ explains Jim Linderman between sips of black coffee from a cup that sits far too close to his sprawl of vintage photographs for the comfort of a visitor who had traveled last December to meet him at his modest home in the lakeside town of Grand Haven, Michigan. ‘Me, I’ve always done things in themes.’

Many collectors of obscure Americana might find sufficient satisfaction in possessing a rare postcard of a Midwestern river baptism, which flourished, cannily publicized by revivalist preachers, from the 1880s through the 1930s. Linderman, on the other hand, searched ‘river baptism photo’ on eBay daily for a decade and purchased every single example he could find until he virtually exhausted both the field and his own acute interest. ‘I didn’t have much competition, really,’ he says dryly.

Over the past three decades, the work of collectors like Linderman has begun to dovetail in fascinating ways with a growing movement in the museum and gallery world to build collections by self-taught and outsider artists.

An ex-librarian and former 60 Minutes fact-checker, Linderman calls his collecting both ‘hobby and life,’ as if there is no possible way, at the age of 65—perhaps there never was—to distinguish between the two. He seizes upon a specific, esoteric theme, educates himself deeply and then accumulates work in that vein for years or even decades, publishing his findings on his blogs or in limited-edition books. He defines his range broadly and somewhat obliquely as ‘antiques, photographs, folk art and unusual items of curiosity.’ His evolving repository of material culture fills almost every surface in his office and shed, as well as his popular blogs (Dull Tool Dim Bulb, Old Time Religion, the now-defunct Vintage Sleaze, and his most recent, the highly specific Sewer Tile Sewer Pipe Pottery) and his illustration-heavy books. In the case of his river baptism photographs, Linderman not only assembled a book (with an introduction by Luc Sante) and a (Grammy-nominated) CD with rare repackaged gospel songs; his images also gave rise to the 2011 exhibition ‘Take Me to the Water: Photographs of River Baptisms’ at the International Center of Photography in New York. Linderman and his wife, Janna Rosenkranz, went on to donate the photographs to the ICP’s permanent collection.

Selections from Linderman’s collection of sewer pipe sculptures made by workers from leftover pipe clay. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

Inside Jim Linderman's home in Grand Haven, Michigan, 2018. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

Though he is the kind of person who distrusts superlatives, Linderman is widely regarded as one of the foremost figures in a field of vernacular art collectors working beyond the margins of most institutional axioms and impulses, in what is essentially its own self-taught art form. Vernacular art is one of several alternatives to outsider art, a term that Linderman and many of his fellow collectors regard today with some distaste. The concept originated with Jean Dubuffet, who coined the term art brut, or raw art, in 1945. Dr. Valérie Rousseau, the curator of self-taught art and art brut at the American Folk Art Museum in New York, said Dubuffet thought of the term as an admiring category to encapsulate art produced by ‘the marginalized, psychiatric patients, prisoners, eccentrics, psychics, recluses and anarchists—each entrenched in their own way in a mind-set that reinterpreted collective values.’ In 1972 British writer Roger Cardinal proposed the designation outsider art as an English-language response to art brut.

But the term has come to be seen as inadequately elastic, superficially lumping together artworks and artists that in fact share little common ground beyond their exclusion from a somewhat nebulous ‘inside.’ Self-taught, vernacular, folk and, most recently, outlier (a term offered by the curator Lynne Cooke in her celebrated ‘Outliers and American Vanguard Art,’ an exhibition that opened last year at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.) are substitutes with arguably more nuanced and sensitive connotations, though Linderman believes that the entire outsider concept and its canon are more a marketing scheme than anything else. ‘Who determines what art belongs next to another?’ he asks. When he speaks about people he calls ‘money artists,’ or institutionally canonized outsider masters—such as Bill Traylor (1854–1949) and Henry Darger (1892–1973)—he notes that many such artists don’t belong in the same curatorial categories and that their work would never be lumped together that way if they were ‘insider’ artists. Furthermore, he adds, the term isn’t even helpful as a descriptor of context: Some self-taught artists work in isolation as ‘communities of one,’ while others are part of particular marginal or localized histories and traditions.

Over the past three decades, the work of collectors like Linderman has begun to dovetail in fascinating ways with a growing movement in the museum and gallery world to build collections by self-taught and outsider artists and to incorporate this art into the history of the 19th and 20th centuries, not as some kind of sideshow but fully as part of the canon. (Alfred H. Barr Jr., the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, first championed the effort, heroically but ultimately unsuccessfully, in the 1930s and 1940s.) This reframing has gained speed recently with prominent exhibitions like Massimiliano Gioni’s ‘The Encyclopedic Palace,’ the main presentation for the 2013 Venice Biennale, which mingled insider and outsider work in ways meant to obliterate the categories altogether—categories already under attack by major artists like Jim Shaw, Richard Prince, Allen Ruppersberg and Mike Kelley (1954–2012), whose collecting of vernacular and popular material both shaped their work and became a form of work in its own right.

Linderman lived in New York for many years, and in the 1980s he frequented contemporary art galleries in the East Village, where he fell in love with work by Neo-Expressionist painters like Eric Fischl and Julian Schnabel—work he wanted but knew he could never afford. Some of the appeal of vernacular collecting, back then, was simply financial. ‘It was a refuge for people who wanted art but wanted a deal, right?’ he says. Linderman would typically pay no more than $20 to $50 for an individual piece, or seek out artists to purchase works in bulk (‘20 for $500’). Sometimes, he’d even acquire pieces for free. Once, driving around the Mississippi Delta, Linderman happened upon what he called ‘the most beautiful quilt I had ever seen’ hanging from a clothesline in a woman’s yard. At the time, he was amassing a collection of quilts by African-American makers. Linderman knocked on the woman’s door and asked if he could purchase the one hanging with her laundry; thinking that he was cold, she insisted instead on giving it to him. In addition to being a fan of the good old-fashioned yard sale and eBay, Linderman is particularly partial to flea markets. He remembers once running into Andy Warhol at one on 23rd Street in Manhattan. (Warhol is said to have thrifted and antiqued every day. His well-known hoarding problem made entire rooms of his Upper East Side townhouse uninhabitable.)

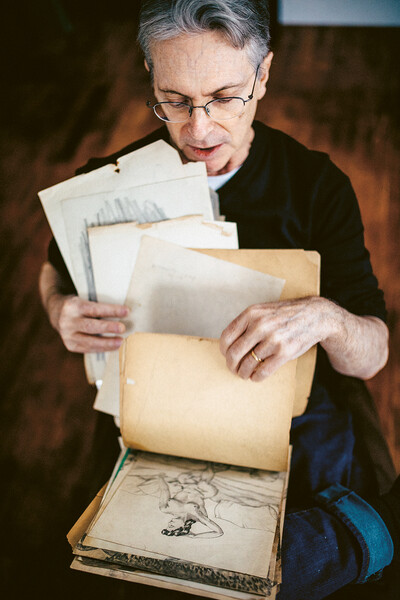

Jim Linderman. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

We spend some time peeling back plastic sleeves to look at old photographs, an undertaking that prompts a flurry of stories. Linderman and his friend Jay Tobler, with whom he shared common collecting interests, went on a road trip through Georgia in 1995. They came across what Linderman describes as a ‘Bible-themed amusement park,’ a sculptural environment built by the Reverend John D. Ruth outside the tiny town of Woodville. Designed as a drive-thru spread across 23 acres, the installation featured statues and paintings scrawled with biblical inscriptions. (The Reverend Ruth’s garden is no longer extant but lives on in photographs by Linderman and others.) Around the same time, Linderman and Tobler paid a visit to Elder Anderson Johnson, a preacher in Newport News, Virginia, who regularly held religious services and musical performances for a congregation consisting of numerous painted portraits hung from his ceiling. Today one of Johnson’s paintings, Female Portrait (1994), lives in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., gifted by Herbert Hemphill Jr., the pioneering folk art collector and first director of the Museum of American Folk Art.

When I ask Linderman about his seemingly limitless interest in religious art, he says that religious art-makers tend to be the variety producing the most impassioned outpourings of work. ‘More motivation,’ he explains. The conversation turns to Sister Gertrude Morgan, a self-taught African-American artist and street preacher whose work is also in the Smithsonian (donations by Hemphill and the folk-art-collector couple Chuck and Jan Rosenak). Morgan used a steak bone as a stylus to dot eyes on the figures in her paintings. Linderman owned the bone for a time and eventually sold it for $100. ‘Who wants a bone?’ he asks with a laugh but then adds with quiet earnestness: ‘That was a tool of her ministry. How can you even put an aesthetic or value judgment on something like that?’

Morgan is one of about 20 vernacular artists whose reputations were established by the Corcoran Gallery of Art’s landmark 1982 exhibition ‘Black Folk Art in America: 1930–1980,’ which Sarah Boxer described in The Atlantic in 2013 as ‘the birth of the American self-taught canon.’

‘I value the free-hand inconsistencies, the asymmetry, the found objects—when there’s so much in the world that’s presumably perfect.’

Previously, such artists had been known predominantly only in their local communities. (One of the show’s stars, William Edmondson, a self-taught Tennessee sculptor and janitor whose religious visions inspired him to fashion tombstones from scavenged materials, had actually gotten his first big break in 1937 after Barr encountered his work through photographs and mounted an exhibition of 10 pieces, MoMA’s first-ever solo show dedicated to an African-American artist.)

The mainstream art world’s interest in vernacular art has ebbed and flowed over the decades. Around the time of Edmondson’s solo exhibition, new fieldwork by American folklorists piqued interest in what was then mostly labeled naive or primitive art. (Linderman notes that the first institutional exhibition of a cigar-store Indian carving also occurred in the 1930s.)

The current wave of interest shows no signs of ebbing. The annual New York Outsider Art Fair turned 27 this year, and the Atlanta-based Souls Grown Deep Foundation, the brainchild of art historian and collector William Arnett, who built a collection of more than 1,000 pieces by self-taught Southern artists, has recently been placing works strategically in important museum collections, including those of the Brooklyn Museum, the Dallas Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which mounted a well-received show of its holdings last year. Not surprisingly, this institutional validation has begun to lift the market value of such works; Christie’s posted a ‘hot list’ of outsider artists in advance of its January 2018 ‘Outsider and Vernacular’ sale. Of Traylor, one of the artists featured in that sale, Linderman now says wonderingly: ‘All those little Traylor paintings were a dime each. There are around 1,500 of them. They’re now $50 grand apiece.’

Jim Linderman. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

We set market talk aside and head to Linderman’s office, where an assortment of odd, small-scale brown sculptures line the shelves. Roughly fashioned by hand from clay, they include a planter in the shape of a tree stump, a charmingly corpulent groundhog, several misshapen heads, and a miniature top hat. These are sewer pipe sculptures, made by bored Midwestern laborers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries from vitrified pipe clay, a widely used material for American sewer systems at the time. At the end of the workday, for their own amusement, sewer workers would fashion modest sculptures from leftover pipe clay before it hardened and became unusable. This pottery has been Linderman’s obsession for the last two years. He laments that there is only one book dedicated to the topic, Jack Adamson’s out-of-print 1973 Illustrated Handbook of Ohio Sewer Pipe Folk Art. In addition to the pipe sculptures, Linderman is also currently collecting photographs of an unscrupulous pastor who rose to fame by preaching from a boat in New Orleans. The preacher (whose name Linderman would rather not disclose for fear of inviting unwanted collector competition) ultimately went on trial for murder following a catastrophic attempt to heal a congregant’s back. Linderman plans to turn his findings into his next book.

Linderman knocked on the woman’s door and asked if he could purchase the [quilt] hanging with her laundry; thinking that he was cold, she insisted instead on giving it to him.

I ask him whether he has ever pursued a holy-grail piece. ‘I’ve owned a holy grail,’ he replies. The work he deemed such was a beautiful jug by a potter and slave named Dave (David Drake) in Edgefield, South Carolina. While it was illegal for slaves to become literate, Drake somehow learned to read and write, and he inscribed his own poems on the vessels he produced. ‘He had initialed the jug with his owner’s name, LM, for Louis’ Linderman says, then he adds solemnly: ‘I realized that his jugs today are selling for 10 times what Louis Miles paid for Dave himself.’ Linderman eventually sold the jug to an up-and-coming African-American collector. ‘That was a pretty informed move for a young collector,’ he says. ‘She understood the piece.’

Inside Jim Linderman's home in Grand Haven, Michigan, 2018. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

I asked Dr. Rousseau of the American Folk Art Museum what makes a good collection of outsider art. ‘A compelling one depends on the collector, the storyteller, on a capacity of persuasion, clarity of intentions,’ she said. ‘And the ability to highlight remarkable expressions where least expected.’

While Linderman’s compulsion to collect is executed with scholarly rigor, it arises primarily from that love of the least expected and also from a place of fundamental tenderness: a love of the clumsy and the unpolished, of objects that bear deeply human histories. ‘There’s a pathos in almost everything I collect because they tried, but didn’t quite make it’, he says. ‘I value the free-hand inconsistencies, the asymmetry, the found objects—when there’s so much in the world that’s presumably perfect.’