Conversations

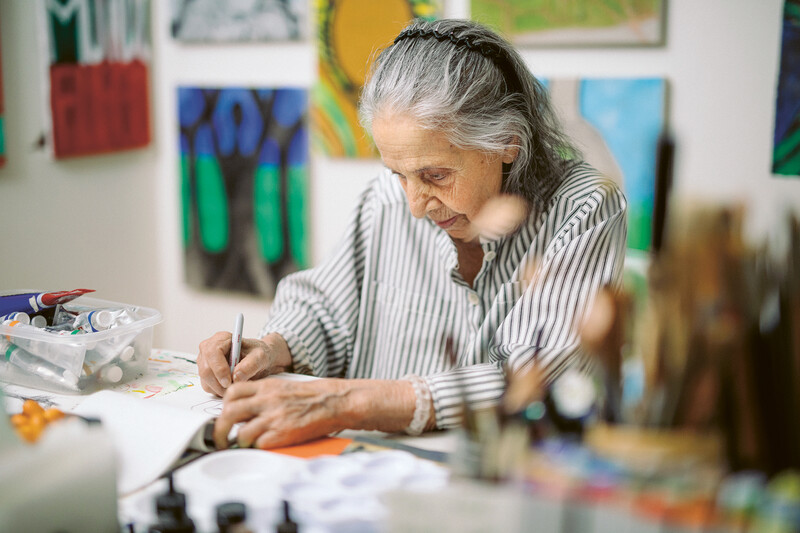

The Painter and the Planetarian: Luchita Hurtado

In conversation with Andrea Bowers about history, nature, and art as a form of shouting

Luchita Hurtado in a section of Malibu, California, devastated by wildfires. Her recent work focuses on climate change and her fears about the environment. Photo: Max Farago

If, as Isamu Noguchi once said, ‘We are a landscape of all we have seen,’ then the painter Luchita Hurtado encompasses a particularly vast, astonishing stretch of terrain, one that takes in Venezuela, where she was born, as well as New York, Mexico City, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Taos, all which she has called home. It includes Noguchi himself, with whom she became close in the mid-1940s, and the other artist friends and acquaintances who have come along the way in her 99 years: Leonora Carrington, Frida Kahlo, Rufino Tamayo, Man Ray, Agnes Martin. It pulls in the movements she has seen come and go (and come again)—Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop, Neo-Expressionism. And it enfolds her family—her sons, Matt Mullican, the artist; John Mullican, a Los Angeles writer and filmmaker; Daniel del Solar, a Bay Area media activist, photographer and poet, who died in 2012; and Pablo del Solar, who died from polio as a child.

Throughout her life in the art world—including her marriages to the Austrian Surrealist Wolfgang Paalen and the Bay Area Abstractionist Lee Mullican—Hurtado worked diligently herself, though she showed her paintings and drawings so rarely that even friends sometimes did not fully understand that she was an artist. That obscurity lifted in dramatic fashion beginning in 2016, when the Los Angeles gallery Park View showed early work, and then especially last year, when the Hammer Museum’s biennial ‘Made in L.A.‘ survey included her at the urging of one of its curators, Anne Ellegood, who visited Hurtado’s Santa Monica home and studio. (In The New York Times, Holland Cotter called the work one of the ‘hands-down stars’ of an especially strong show.)

After a solo New York exhibition at Hauser & Wirth’s Upper East Side gallery in early 2019, her most prominent appearance ever in her former city, she was featured in May in a survey, organized by Hans Ulrich-Obrist, at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery in London, and in fall 2020 will debut in Mexico City at Museo Tamayo, founded by her old friend.

In early January 2019, Hurtado—whose most recent work has turned intently to nature, revolving around the threat of climate change and environmental degradation—invited the Los Angeles artist and activist Andrea Bowers to her studio for a wide-ranging conversation.

‘[For those who neglected my work,] I don’t feel anger. I really don’t. I feel, you know: ‘How stupid of them.’ Maybe the people who were looking at what I was doing had no eye for the future and, therefore, no eye for the present.’

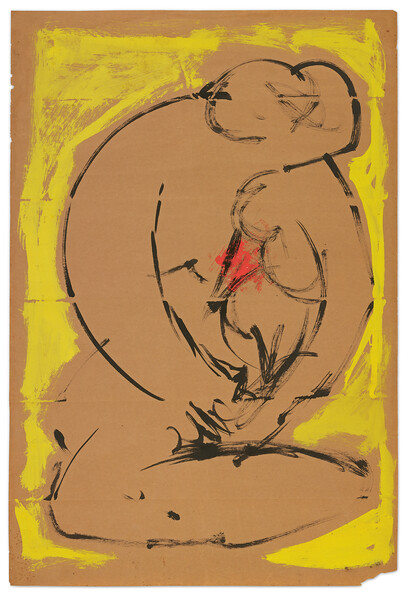

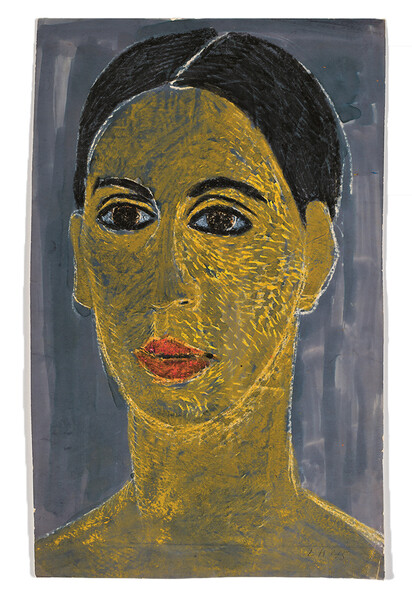

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, c. 1981 © The Estate of Luchita Hurtado

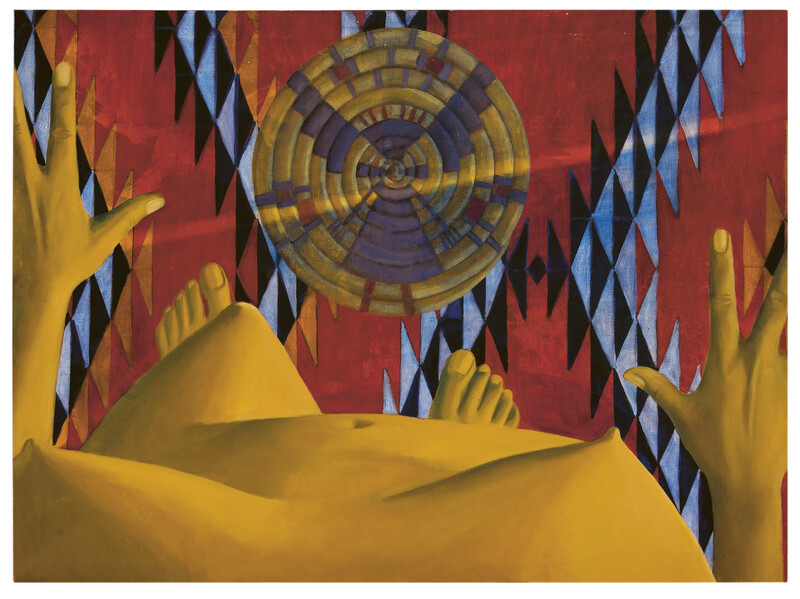

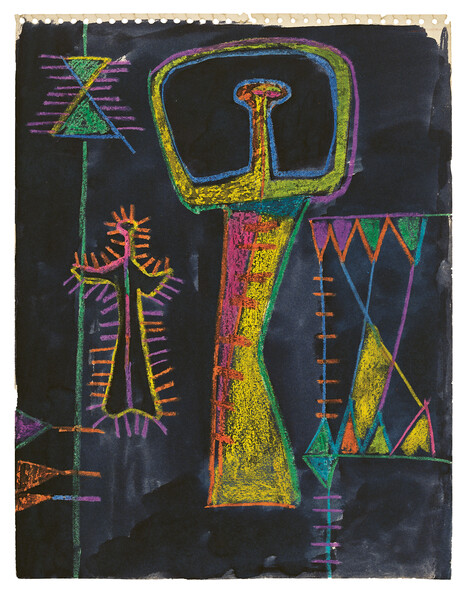

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, c. 1947-1949 © The Estate of Luchita Hurtado

Andrea Bowers: Where should we start?

Luchita Hurtado: Well, maybe I should start by asking you a question about how you feel about…No, I guess we shouldn’t be political, should we?

AB: We have to be political! I mean, that’s all I am. I can’t help myself. I can’t say ‘Boo!‘ without it becoming political.

LH: Okay, but with the politics now, there are certain names that probably shouldn’t be spoken out loud.

AB: I’m with you there.

LH: I mean, fascism is alive and well again in certain minds in this country.

AB: You know, on that topic, I read about when you studied at the Art Students League when you were living in New York in the 1940s and that you’d also worked for the Spanish newspaper 'La Prensa' back when fascism was the topic of the day. I took drawing classes at the League once myself when I was in New York. Can you talk about the politics then?

LH: I’m 98 now, and when I think back to those years, things come and go in my mind. I can’t visualize it. But if I wait a bit, it comes to me. Sometimes I wake up seeing my father’s face. He had green eyes, and I see him clearly, when I was young in Venezuela. I have this scar under my chin. I remember waiting for him once in the zaguán—that’s the space between the front door of your house and your gate. I see these things that come without even asking…unconnected to anything. I remember just by feeling this scar, me waiting for my father. And when I saw him turn the corner, I would run to him, and once I fell. So the scar is the memory.

AB: That’s a beautiful story. I lost my mom four years ago. She had stage-four brain cancer for 12 years.

LH: Oh, how awful. How awful.

AB: But she lived with it. She fought it! She was so strong, and I’m so grateful for those years with her. I worry about my memories because she was the most important person in my life, so hearing that memory can remain gives me so much hope. It’s the one thing I don’t want to lose.

Hurtado’s most recent work. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

Hurtado at her studio in Santa Monica, California, January 2019. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

LH: Well, there are things you have to live with. You know, once when I was driving, my son and I, from Santa Fe to Taos, where I have a house, I suddenly discovered I couldn’t go there anymore because it’s too high and I couldn’t breathe. I used to be able to exercise, do everything there, and now I can’t, so I don’t go anymore. I gave my son the keys. It’s his house. That’s what happens. I’ve learned to accept that whatever comes with life is fine, it’s welcome, because that’s the way it is. And I’m learning a lot. There are a lot of things I didn’t plan on because you have to live it to know it, to really see what comes with 98 years old!

AB: Well, it’s impressive, and all this new work is impressive, too.

LH: I just feel very lucky that I can still work, that I’m still interested, that I’m still involved.

AB: I guess that talking about these fascist movements that are coming up again, it must be like having your own memories returning. Like, ‘Here we go—fascism again,’ right?

LH: It’s too short a time. It seems like it happened not so many years ago, that we were all involved.

AB: I know from reading that we have something in common in our work. One of the biggest issues in what I’m doing right now is what’s called climate justice.

LH: And that’s what my work has now become.

AB: Let’s talk about that. What are you thinking?

LH: The most interesting thing for me now is to make sure that the planet is going in the right direction. I keep the words 'sky, water, earth, fire' in my mind. Those are the elements, and that’s what my work has come to be about. That’s what I’m about. Here I am, you see? That’s me and the trees, and we are related. [The two look at a recent painting on Hurtado’s studio wall that depicts a dark figure between two trees, over the words ‘Air,‘ ‘Water,‘ ‘Earth‘ and ‘Fire.‘]

AB: God, I love that painting. Why did you choose the black?

LH: Because it looks good.

AB: [Bursts into laughter] Perfect. You’re right. Oh, my god, I’m overeducated. I can make up so many ways of trying to explain why I choose something, when the truth often is: It just looks good!

LH: When I think about my painting and the political and the planet, it’s about the hope that it’s not too late and that people can still get together and in whatever small way make a difference that adds up. As far as physical strength and ability goes, I’m very weak, of course, because of my age, but I still can paint, I can still draw. And so that’s my contribution.

AB: Well, not only that. You’re an art star now!

LH: I’m a what?

AB: You’re a big deal now, so you have a huge voice. What does it feel like after working so long to suddenly feel that you have this huge career, at your age?

LH: I’m always just surprised that I’m here where I am, and there are a lot of people to thank for what’s happening now.

AB: Yourself, most of all. The work deserves to be seen, and it’s past due. Looking at the work today made me think about my generation, about what we reaped in benefits from second-wave feminists who were making the world a better place for women. But I somehow didn’t realize that even I grew up in a time of patriarchy, in a way. It wasn’t until the Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court hearings when I realized: He’s my exact age. I grew up with guys like him. Thinking about the kinds of patriarchy you’ve seen, I can’t even imagine. Your work should’ve been shown—and known—a long time ago. I’m a little mad about it.

LH: I’m not.

AB: No? Okay, then let me have all the anger. I’ll have rage for you.

LH: You see, no, I don’t feel anger. I really don’t. I feel, you know: ‘How stupid of them.’ Maybe the people who were looking at what I was doing had no eye for the future and, therefore, no eye for the present.

AB: Looking at all this work, I keep wondering how you seem to be able to shift so easily between representation and abstraction, between different types of paper and materials, different techniques. I do that, too, moving pretty quickly between things, but I don’t know if I have that kind of fluidity. Where do you think that comes from?

LH: You know, when I go to dinner, I always say, ‘I want to be the last to order.’ And the reason is because whenever anybody orders the food, that’s what I want.

AB: My grandmother did the same thing: ‘I never want what I order. I want what everyone else orders.’

LH: Yes, but in the end, you have to order something, so I do. I don’t know if that really explains what you’re asking, but I guess I see what I want to make and then I do it. I enjoy life, and I feel I’ve been different people. I was a different person, for example, when I did these very sexy drawings and paintings of my body, looking at my body. [Laughs] It’s the truth. Sex was all I could think about.

AB: That’s awesome.

LH: Well, it’s true. I really get involved in whatever it is I’m doing at a certain time.

AB: [Looks at paintings that depict the length of Hurtado’s body from the perspective of her own eye level, a recurrent motif in her work in the 1970s.] Were you standing naked and smoking in a closet when you were making these paintings?

LH: Yes! And that’s part of the open door and the light coming in. It’s real time and real space.

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, 1954 © The Estate of Luchita Hurtado

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, 1969 © The Estate of Luchita Hurtado

AB: I saw a couple works on paper, too, that have that beam of light. I like that beam of light. I always loved those Sylvia Plimack Mangold pieces in which she’d paint corners of her house, rooms where she was. They were super influential to me. I always felt like she felt cornered in some way, and sometimes there would be clothes on the floor, and she’d paint the floor. But there was almost always light, a beam of light or light coming through a window. For me, that was about hope, in some way.

LH: I have a painting of mine—I don’t know where it is, whether it sold or not—where I’m standing nude, very relaxed about it, and I have a cigarette in my hand. I didn’t know at that time that smoking was bad for you, of course.

AB: Nobody did.

LH: I started when I was living in New York and working, looking after two children and so much freelance work to do, and so I went to a pharmacy and said, ‘I want to have something that will help me stay awake.’ And the man was very upset with me. He said, ‘You New Yorkers just want to work all day and play all night. No, I’m not giving you anything. ‘Then a friend of mine said, ‘Don’t be silly. All you have to do is smoke cigarettes to stay awake.’ And so I did, and it worked.

AB: Yeah…nicotine. Very bad for you. But it also made for great subject matter for the paintings. Did you have a mirror above you when you did these paintings of your body? How did you do them?

LH: No, no. Actually, you don’t need it. I think you can see yourself.

AB: The foreshortening is super interesting in those paintings; not easy to accomplish.

LH: [Points to a blue-and-gray near-abstract painting on the wall, with curved and circular lines that evoke a woman’s raised legs and abdomen.] This one is about birth, a very painful process.

AB: I don’t have kids. I’m not as strong as you. I couldn’t do it.

LH: It’s an amazing thing. There is a feeling about a child in your arms that is…you know, the smell of the head, the whole thing. You become nature. We are all related. And there is this absolute love that you have for your offspring that doesn’t exist anywhere else. It’s a very animal experience. Terrestrial.

AB: I feel that way about my cats. [Laughs]

LH: Why not? There is that part of cats that is very human.

AB: At least they keep me company while I work.

LH: I had a cat in Mexico. His name was Pichano. A great cat. Short hair. And Pichano followed me always to the studio, and he was there with me, and one day I saw this bird at the market, and I had to have the bird. I brought the bird home, and the cat never forgave me. He stopped coming into the studio. This great love affair we were having ended, and that was that. I learned the hard way.

AB: While we’re on the subject of self-portraits, can you tell me about that one you did of yourself as a mop?

LH: Oh, that. I was feeling very low. I was feeling neglected, unloved.

AB: In terms of not being appreciated for the work you were doing? Or for doing the kind of domestic labor that goes totally unrecognized?

LH: All of it. That was a good painting.

AB: Maybe it’s too far back to talk about, but I’m obsessed with trying to learn about second-wave feminism and what went on here with women artists in LA. I know that you had that stunning show in 1974 at the Women’s Building [the feminist art space in downtown Los Angeles that existed from 1973 to 1991]—your last solo show in this city! I saw some pictures from that show, and I got to see some of the work today.

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, 1969 © The Estate of Luchita Hurtado

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, 1969 © The Estate of Luchita Hurtado

LH: That goes back to what we used to call ‘consciousness-raising.’ There were meetings every week. I remember Alexis Smith and Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago—so very important.

AB: Judy is also, for the first time, it seems to me, finally being recognized in the marketplace. Both of you are showing at the same level right now, I would say, after all these years. Last time I saw Alexis, she was so full of life and lecturing me: ‘Get a job, Andrea! Get a teaching job.’ I was like, ‘I don’t want a teaching job!’ She was like, ‘You can’t trust men, you can’t trust the art world. Get a job.’ [Laughs] It’s so exciting to me that I get to live in a time where women of your generation—Judy and Miriam and Suzanne Lacy, that whole generation of pioneering feminists—is finally getting recognized. It’s about time.

LH: It is. Too late for some.

AB: I have a question for you about your biography, but it’s not really a biographical question. The life you’ve led is super impressive, of course, but at the same time, I don’t think it’s as impressive as your art production. I don’t like that the two get crossed over in certain ways, that your biography gets promoted as your art practice, or obscures the work.

LH: A long time ago, people would say, ‘Tell us about you,’ and I would say to myself, ‘There is nothing impressive about you. What are you going to say?’ Then I would answer myself, ‘Make it up.’ And so I did. You know, I’d say that I went to this great school, and I did this, and I did that, and people listened and thought it was all real, but it wasn’t. My beginnings were really not much. I arrived in America when I was eight years old. I had been living with two old maiden aunts, with a brother. My mother had taken my sister to America at one point, so my first memories don’t include my mother at all. They are instead of these two wonderful old aunts, one of whom was always in the kitchen cooking. The kitchens at that time were outside in Venezuela, in Caracas, because they used wood; there was no gas. The 1920s! Not even a telephone. That was a long time ago. I remember playing outside with my dolls while my old aunt cooked, and finding it all very nice. A very rich cousin of mine had this house in the garden, and there was a stream that went through it. I remember sitting in this stream on a very hot day, eating a mango and thinking to myself, ‘Life cannot get better than this.’ I was maybe eight years old. When you think of what was available at that time in a place like Venezuela…

‘When you think of the first cave paintings, they were shouting. They wanted something to eat. ‘Give me meat!’’

AB: Do you think about Venezuela now, what’s happening there?

LH: I do. It’s very sad. There’s not even any food to eat.

AB: A lot of it has to do with what we’ve already been talking about here, or at least alluding to: the government invested everything in oil, and now it’s destroying the country, in addition to destroying the planet. Disaster capitalism.

LH: You know, money is responsible for many good things, too. It’s how you use it. There will be a solution to what we’re doing to ourselves and the earth. I have great hopes.

AB: Okay, I’m trusting your wisdom. We’re both doing the same thing, trying to figure out how to work through all these issues as artists.

LH: I still do trust the better nature of people. Even now.

AB: Thinking about that kind of optimism, I wanted to ask you about having a sense of humor. I did this performance project once, an endurance piece with Suzanne Lacy, the performance artist. She doesn’t make objects, so it was my job to teach her how to draw, which was nearly impossible, but it was really about having my generation in conversation with artists of her generation, now in their seventies and early eighties—to have intergenerational discussions through the medium of drawing, basically. We did another one here in Los Angeles in which Suzanne and I lived together for 10 days, and she taught me about performance art. It was kind of crazy. It was exhausting, and we nearly killed each other. Intergenerational feminism isn’t always pretty, but it’s really rewarding. And one of the things it made me realize is that my generation has no sense of humor. Your generation, in particular, seems to have an amazing sense of humor. I think it’s kind of tied to the politics of being a woman, a way to be critical and to be empowered through humor. Somehow, my generation lost that. We aren’t funny. How does humor function for you?

LH: I think that whoever made us must have had a sense of humor, right? I think it was given to us. It’s a blessing to have, because you might be aching with pain, but you’re laughing about it.

AB: I think there are funny things in your art. Is that okay to say?

LH: Oh, yes. And I accept it. I think the whole thing is really hilarious.

AB: Making art?

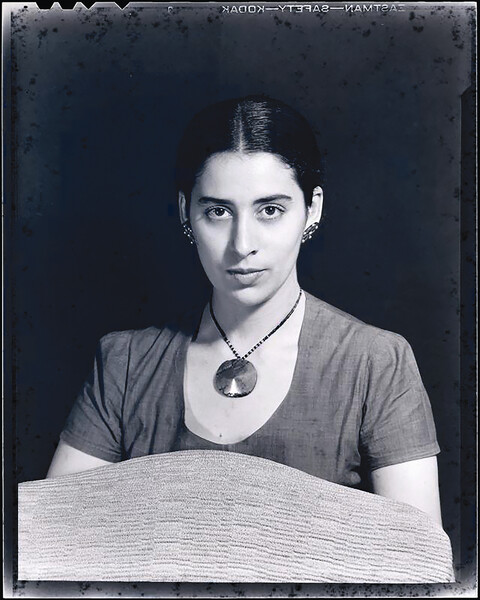

Luchita Hurtado, 1947 © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society, New York/ADAGP, Paris

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, 1945 © The Estate of Luchita Hurtado

LH: No, being human! Making art is kind of like shouting for me. ‘Look here! Look here! Please help!’

AB: I always say to my students, ‘Imagine as an artist that you have a soap box, and you have 30 seconds to say something to the world. What are you going to say? ‘I like kitties’? ‘I like surfing’? It really is like shouting, and you have to make up your mind what you’re going to shout.

LH: When you think of the first cave paintings, they were shouting. They wanted something to eat in those caves. ‘Give me meat!’

AB: Now they think a lot of those pictures were drawn by women.

LH: Really? Well, I’m glad to hear that. It used to be that you could camp right at the mouth of those caves, and I did it. My husband Lee and I went off on this trip to Spain along the coast, and we came to these wonderful places, and you could camp right outside. The cave where we stayed was looked after by one family.

AB: Whoa.

LH: And you could go in and out and stand right in the place where the person must have stood who made the paintings so many thousands of years ago. It was an extraordinary experience to stand there and, in a way, to mentally touch the hand of your ancestors. We went back to the caves after years passed, and you had to make an appointment to go in, for 15 minutes only. Now you can’t go in and see them at all. They’ve had to make a duplicate, a simulacrum, with digital means. I don’t blame them. It’s too many people. We’ve overpopulated everything. [Hurtado pauses and offers a bowl of fruit to Bowers and to others in the room.]

LH: Please, everybody, have a kumquat.

AB: I’ve read a few pieces that talk about you hiding your work for many years and not showing it to people. Can you speak about why you felt the need to do that?

LH: I guess it was partly because in the beginning, my mother and stepfather really weren’t interested in what I was doing or what I was about. Once we were in New York, my mother wanted me to go to a school to learn dressmaking. But I chose Washington Irving High School near Gramercy Park, where I learned a great deal from the other pupils, not so much from the teachers. I learned about the opera. I learned about movies and actors. For instance, Orson Welles, who at that time was at his best, with that great voice of his—we would go to the Mercury Theater on 41st Street and wait outside the door to see him. I learned from my contemporaries, because in my world, my family was completely out of it.

AB: But later on, when you were among other artists, when you were painting at night, you weren’t really showing your work then either?

LH: Well, I married when I was 19, straight out of high school. And I married a man, unfortunately, who, soon after I had two children, just came for his books and left, and I never saw him again. He just disappeared. And he married again. I never really felt that I had the time to show people my work, or that there was any interest. To make money, I began doing window displays for Lord & Taylor.

AB: With all of these things that happened to you—some of them traumatic—and with you moving so much, how did you keep track of your artwork?

LH: I didn’t. I lost a lot of it. I don’t have much from the early years.

AB: There’s a young curator and collector here in Los Angeles, Olivia Marciano, from the Marciano family and the Marciano Art Foundation, and I think about her in the context of your work because she’s been thinking a lot about spirituality in women’s art. We’ve been interviewing a lot of feminists and women artists about it. I was wondering if you could say a little bit about that in your work. I’m not talking Christianity; I’m talking about the way that women have used different types of spirituality to invent experience, to get through things, as a kind of medicine, because medical care for women has always been bad compared to care for men, for example.

LH: In our family in Venezuela, there was a background of that kind of belief and practice, but by the time I came along, people didn’t admit to it.

AB: Do you mean shamans?

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, c. 1950 © The Estate of Luchita Hurtado

Luchita Hurtado, 2019. Photo: Max Farago

LH: Native heritage in your bloodline, and native traditions and beliefs. People just didn’t talk about it. They did not admit to it. They made fun of it in our family. It was really hard to get any truth about it. There were people like me in my family who were very dark. When I used to go to my house in Taos, New Mexico, and go to watch tribal dances, they wouldn’t ask me if I was Indian; they would say, ‘What tribe are you?’ I would say, ‘Venezuelan.’ And they’d say, ‘I’ve never heard of that one!’ Once I came to the United States, people would always come up to me and say, ‘Can I take your picture?’ because I looked somehow, I don’t know, extraordinary to them.’

AB: You felt exoticized in a certain way?

LH: Yes. But also, within myself, I felt that I was Indian. I felt that very much when I went to the dances, because the tribes had a complete attitude towards the earth, that it was alive. I remember asking why the dances in the winter were different from the summer dances. A lot of stomping went on in the summer. I asked a man about this once, and he said, ‘Because the earth is asleep, of course, in winter.’ Instead of stomping, they drag the foot, so as not to wake the earth. It’s an attitude toward the planet as a living thing. Every person is different. For me, what works is feeling like a planetarian. Being a planetarian will bring out a lot of stuff that you didn’t know you had in you.

AB: What is a planetarian?

LH: Well, that you are looking for the world to survive, really. We’re all here together. We’re all involved with this. [Points to the ceiling, as if to outer space] Out there, there’s no air, let’s face it. And everything here breathes. The trees breathe out, we breathe in. We are related to everything here, and nothing really ever goes away. I think probably, at some point, we will be able to hear people who are gone, when we get the right machines. We’ll be able to hear Napoleon. Let’s hear Napoleon on next week’s program! Or George Washington. Let’s hear Washington’s address to Congress.

AB: You think they’re going to invent a machine that can go back in time?

LH: Of course. Because it’s all here, you see? It’s around us.

AB: Who or what would you want to hear?

LH: Oh god, I’m not clever enough to be able to give you a direct answer.

AB: I mean, I’d love to be able to hear someone like Sojourner Truth or Emma Goldman. Or hear the speakers at Seneca Falls, the historic first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls in 1848. Something like that. Of course, I’d also love to just have some time with my mom again.

LH: Well, there, of course. I think you do meet again, in this world.

AB: You do?

LH: I think so. I remember talking about this when I was with my son John once. We were driving through a terrible electrical storm, and I was sure we were not going to make it. I kept saying to John, ‘I hope we’re going to the same place!’ He was very calm and worldly about it all. He said, ‘Oh, mother, we have rubber wheels. We’ll be fine.’

AB: So, to try to conclude here, because I’ve been talking your ear off, and you’ve been so generous to do this, do you have any advice for me or for younger women artists? For myself, I’m trying to move more with love than with fear these days. I think I was not such a good person when I reacted because I was fearful, and I didn’t know it. And I behaved badly.

LH: I would tell you, or anybody, just work away. Paint away. Give your heart to it. Have a good time. Face the world. It took me a while to learn how to do that. But we all know firsthand that doing it is what makes us the happiest. So choose it.

AB: Choose it?

LH: Yes. That’s the hard part. Because, you know, life can take over.

‘Luchita Hurtado. I Live. I Die. I Will Be Reborn.’ was on view at Serpentine Gallery in London from 23 May – 8 September 2019. The artist’s first solo exhibition in Europe traced the trajectory of Hurtado’s expansive career, including her sustained focus on contemporary environmental and political issues. The exhibition travelled to Los Angeles County Museum of Art in spring 2020 and will open at the Museo Tamayo in fall 2020.