Conversations

Angry Birds: A Conversation with Ida Applebroog

The artist Ida Applebroog has worked in SoHo since 1974, more than 40 of those years in a high-ceilinged, whitewashed loft on Broadway near Broome Street—one of the few still virtually unclaimed from its industrial past, a rambling, ragged space of the kind that transformed the neighborhood into an artists’ beachhead beginning in the late 1960s.

Applebroog still lives, as it were, just above the store: her apartment is a short elevator ride down to the studio. The distance serves as a fitting metaphor for the career she has forged during almost half a century—deeply lived, urgently felt, highly idiosyncratic art that has earned her the respect of fellow artists and curators, in part because it has refused to fit comfortably into market or museum paradigms. In drawings, prints, sculpture, installation and film, she has followed her own imperatives, darkly comic and at times ferocious—taking inspiration from forebears literary (Beckett, Joyce) and artistic (Goya, Otto Dix, Käthe Kollwitz), as well as from her involvement in the women’s liberation movement as a member of the pioneering publishing collective Heresies.

Born Ida Appelbaum in the Bronx in 1929 into a deeply Orthodox Jewish family, she married and raised four children, living for several years in Chicago and San Diego, where her husband, Gideon Horowitz (a psychotherapist who died in 2015), held academic positions. In 1975, jettisoning both her maiden and married names, she forged a new identity, calling herself Ida Applebroog, a coinage like something from the Brothers Grimm. The previous year, she had returned to New York and, already in her mid-40s, emerged on the art scene. In 1998, she won a MacArthur ‘genius’ grant. Her work has twice been featured in Documenta in Kassel, Germany, and it resides in the collections of major museums including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Museum of Modern Art.

From late summer through winter of 2017, I visited Applebroog’s studio several times, conversations that took place during a tumultuous time in American history: the early presidency of Donald Trump; the rise of white nationalism and anti-immigrant violence; the #MeToo sexual harassment movement; mass shootings in Las Vegas and Texas. A new body of work in progress during these visits centered on drawings and sculptures of dead birds, complex symbols of violence, beauty, nature and art. — Randy Kennedy

Ida Applebroog in her studio, 2012. Photo: Emily Poole. Courtesy the artist © Ida Applebroog

These are edited excerpts from the interviews:

Randy Kennedy: Should we be old-fashioned and start at the beginning? Not just for the sake of chronology but because what you’ve told me about your early life—a girl in an isolated Orthodox Jewish family, in a family with an abusive father, in a very domineering male world in general—seems to speak volumes right now.

Ida Applebroog: My parents came from Poland, my father first. This was during a time of pogroms, and they were poverty stricken. My father sold salt, whatever he could sell to make ends meet. People had to share what little food they had just to survive. My father came to New York first, leaving my mother and my older sister in Poland for six years.

RK: What was your mother like?

IA: She really had the temperament of an artist. She loved to sew, and that’s how she made her living in Poland. She was a dressmaker. When she came here, there weren’t those kinds of jobs. But she sewed everything for us—pajamas, coats. Nothing was ever bought from the store. My father was a furrier, so he had a drawer full of all kinds of little pieces of fur, which she would attach onto everything she sewed. I used to be so embarrassed to walk to school. My winter coat would have a rabbit collar on it and little pieces of fur hanging all over. She couldn’t read or write. During the war, we encouraged her, my sister and I, to take a night class. She signed everything only with an X, and she learned, that summer, how to write Sara Appelbaum. It took her forever to get S, the A. She had to erase it. Start again. But she would practice, continuously writing Sara Appelbaum.

RK: How was your father abusive? Was he a large man?

IA: No, he was a tiny man! He wasn’t five feet tall! My mother wasn’t five feet tall. I was the biggest in the family. When he got really angry, he would take pots and pans and threaten to throw them at you and throw them across the kitchen in your direction. He had a very loud voice. When he was displeased, you could hear it from blocks away, but he never really talked much otherwise. It was always: head down, reading a newspaper. My mother was always looking out the window, very depressed. The household was not the best, let’s say.

RK: What was your neighborhood like?

IA: We were near the Bronx Zoo. In those days, it was all Jewish immigrants from Poland, from Russia, from Hungary, from all over. Wherever the Jews were running from. There might have been one non-Jewish person on your block, maybe a black person who was the janitor or the building agent. I remember one man who had an apartment in a building, and there were several buildings that he took care of. He had a Christmas tree. I had never seen a Christmas tree. He and his wife kept inviting me to come in and look at the tree, and when I mentioned it to my mother and my father, they almost passed out. "Don’t you dare. Don’t you go in there."

RK: It sounds like the kind of isolation and poverty that Alfred Kazin wrote about in A Walker in the City, his classic about growing up in Brownsville, Brooklyn, not many years earlier.

IA: I had one year in Brownsville myself. My father had a grocery there for one year. Our life was exactly the same as that book, if I can remember the name of the author…It was as if the writer’s family had exactly the same kind of store. Bernard Malamud! I couldn’t believe what I was reading. [The Assistant, published in 1957, included a character based on Malamud’s father, a struggling Brooklyn grocer.] At a certain point, when I started high school, my father felt it was time enough. There was no more reason for educating me. See, the thing is, if there had been a boy in the family, the boy would have been prepared for yeshiva, and the boy would be this treasured item, but the girls didn’t matter. They had to learn a trade. The earlier they learn their trade to make money to bring into the house, the better. Then somewhere they would get married and have children. And that would be that.

"It’s always your story: It’s never my story, it’s never someone else’s story. You come with the content in your own head and do a Rorschach kind of association, so whatever it is that you’re looking at is a do-it-yourself projective test. But it’s also a chaos of nameless possibilities."

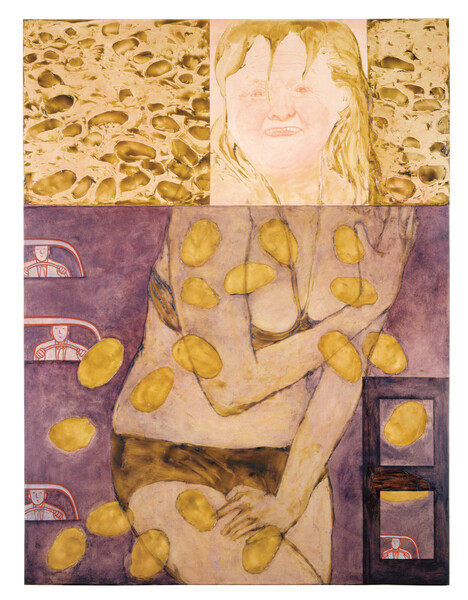

Ida Applebroog, Beulahland (for Marilyn Monroe), 1987. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Stewart and Judith Colton. Photo: Jennifer Kotter. Courtesy the artist © Ida Applebroog

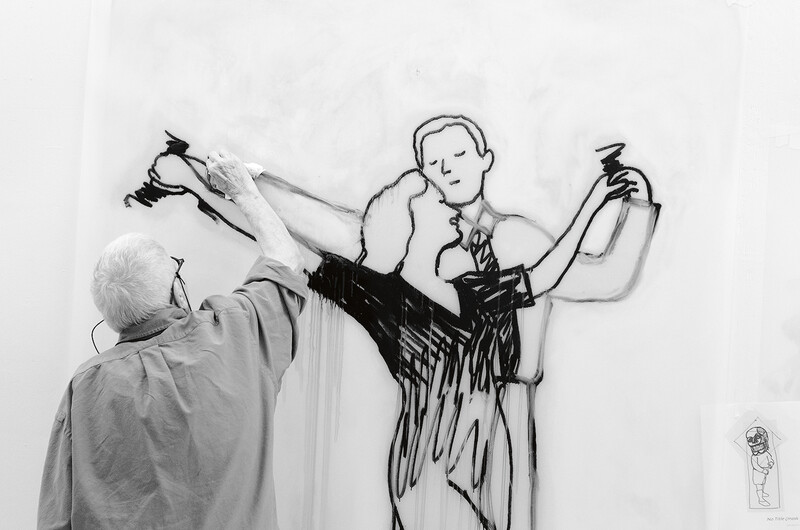

Ida Applebroog in her Broadway studio, New York City, 2011. Photo: Emily Poole. Courtesy the artist © Ida Applebroog

RK: Did your father, because he had daughters, feel…

IA: Cheated? Yes. Cursed. God actually punished him by giving him three girls.

RK: Did he ever say that out loud?

IA: Oh yes. Of course. There was a saying he had, in Yiddish: "You’re better off to have stones than to have children."

RK: How early did know you wanted to be an artist?

IA: I think I always knew somewhere. Once, I asked my father to draw a picture, and he drew a stick figure, and I drew a little princess with a crown on her. I took one look at what my father drew and what I drew, and I was absolutely elated. I was an artist, and I was better than he was.

RK: You knew it.

IA: Five years old and I knew it.

RK: I remember you told me once that there was no decoration in your house, nothing really aesthetic at all, and that you decorated a dresser in your bedroom and got in trouble.

IA: They said I was a schmutzer. I schmutzed everything up. ‘You dirty everything! You’re a shitter-upper!’ Which was true. I was.

RK: Do you remember the point in your life when you realized you didn’t share their religious faith? And that you wanted to be in the wider world?

IA: All I wanted when I was a young, seven or eight, was to live in a nunnery. I wanted to be a nun desperately. I wanted to wear the habit. I wanted no one to be able to see my face really and nobody to bother me the way my parents would bother me with the Hebrew and the this and the that. I had never even been in a church, but I knew about convents and loved the idea of nuns.

RK: Because you knew they had a sort of solitude?

IA: Yes. I knew that nobody bothered them. As long as you’re wearing something like that, who’s going to bother you? I would be respected, and I wouldn’t have to say a word, and nobody would have to look at me.

"I wanted to be a nun, desperately. I wanted to wear the habit. I wanted no one to be able to see my face, really, and nobody to bother me the way my parents would bother me."

RK: When did you start going to museums in the city and begin to see art?

IA: I was afraid of museums. Terrified of them. I wanted to go to some printmaking classes at the Museum of Modern Art, and I didn’t have the nerve. I remember going there, taking one look at the building and the people. They were so sophisticated, and I remember I turned myself around and headed home. I was so terrified that they’d throw me out and see what a fake I was. Instead, as I was going away from the museum, walking around the city, I went past Gimbels, the department store. They were offering a pottery course. That felt safe. Nobody would know or tell my parents, and so I went in and took a pottery course.

RK: Your first job was at an ad agency, after you went to school to study graphic design. What was it like being in the New York ad world at that time?

IA: I didn’t make it very long. Because there were a lot of boys there, and the boys were very free to…you know, with their hands. It was perfectly permissible. It’s still permissible, right? I was the only girl there, except for one stenographer. I didn’t know how to handle it. I didn’t have a big mouth to say, ‘Get your hands off me,’ or, ‘Treat me respectfully.’ They were so nice as they were doing it: ‘Oh, Ida, you’re so beautiful.’ I went to work for the New York Public Library, helping with the famous Picture Collection—it was a dream job. Earlier, I had also worked briefly for another designer, Arnold Arnold, whose wife was the photographer Eve Arnold. At that time, she was starting to go into burlesque houses and do photography there. She had a baby, so when she had to take care of the baby, I was left to take care of her photographs developing in the bathtub.

RK: For someone who came of age before the Pictures Generation—artists like Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, Louise Lawler—and who isn’t identified with that crowd, it’s always struck me how extensively your work draws on mass imagery, pictures from magazines and newspapers, reimagined, burrowed into. Did working around photographs and photographers influence you?

IA: At the library, in the Picture Collection, I was so taken with the images. I was breathless after a day of working with those images. It was a self-education. And I also learned about different artists that I didn’t know because with all these images came the descriptions of what it was and where it was coming from.

RK: Were some of the pictures reproductions of art? You’re getting press photos of things happening in the world, but art, too? A picture of a Rembrandt painting or a picture of …

IA: Everything. You name it, it was there. I learned about artists I’d never heard about. I remember George Bellows so clearly, the painter of the boxing paintings.

RK: When I was a kid in rural Texas, the schools sponsored a statewide contest called Picture Memory. They’d give us postcard-size laminated images of paintings. Then on the back you would have to memorize all the information: the painter, the year, title of the work, nationality of the artist. There was a Leonardo and Chardin’s Soap Bubbles and a George Bellows painting called, I still remember it so vividly, Both Members of This Club, because it was a boxing club, and it was one of those really meaty paintings. It looked almost like Lucian Freud or Soutine. Very meaty, bruisy bodies, slugging each other.

IA: He interested me. Why would I be interested in boxing? I still don’t know why, but he interested me a lot.

RK: To me, they were kind of scary paintings.

IA: Yes, they were. It’s so funny. We have something in common: Bellows!

Ida Applebroog, Trinity Towers, 1982. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and David Roberts Art Foundation, London. Photo: Alex Delfanne. Courtesy the artist © Ida Applebroog

Applebroog in her Crosby Street loft, New York City, 1975. Courtesy the artist © Ida Applebroog

RK: In 1956, you moved to Chicago with your family and later managed to go to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Did you think of yourself as a working artist in those years?

IA: I can’t remember what I thought. But I loved the whole idea of walking through the museum every morning, being that close to the paintings. If the guards weren’t looking, I could even feel the paint and the pigment, whatever it was that was hanging; that was extraordinarily important to me, being let loose in a candy store when no one is looking.

RK: Were there any older works there, canonical works, that really knocked your socks off?

IA: I honestly don’t remember. What I do remember is how important Claes Oldenburg was to all of us.

RK: It surprises me that his influence was already so deeply felt among his peers. He was born the same year as you, 1929.

IA: We were all making little Claes Oldenburgs. We’d put the latex on whatever, on a can or something, on every object that was around to make these little Claes Oldenburg objects. I remember how influenced I was by the kinds of materials he used, everything floppy and soft. Then later came Eva Hesse, and of course she took that softness to the ultimate point at that time, but I didn’t know about her then. The soft sculpture that I did later, when we had moved to San Diego, was a carryover, in a sense, of some of the influence of Oldenburg.

RK: Those are the pieces that I’ve only seen pictures of, that you eventually destroyed because you thought they looked too much like Hesse’s work?

IA: Yes, I don’t remember when I started those, but probably those pieces had come after the hospital. [In 1969 Applebroog suffered a nervous breakdown and spent several weeks in Mercy Hospital in San Diego]. I had started working on those because the first piece reminded me of the form of a lifeboat. It had two openings in it, and you could sit in it like a lifeboat. I used to sit in it and paddle away. It was just my little joke to myself. I made 43 of those forms in muslin and then would hang them in different ways until they became different pieces. I made others that I thought of as game bags, like the kind you use when you’re hunting, to put the animal in after you’ve killed it. All the hunting stores had those. San Diego was full of those.

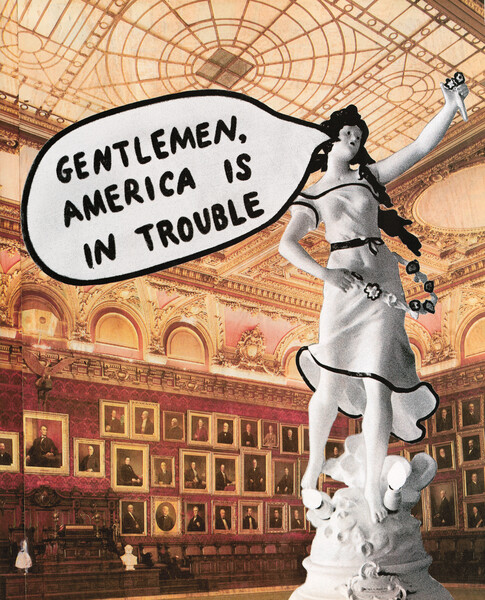

Ida Applebroog, After A. Moreau: Gentlemen, America Is in Trouble, 1982. Installation view, Great Hall, New York Chamber of Commerce (Private collection). Photo: Robin Holland. Courtesy the artist © Ida Applebroog

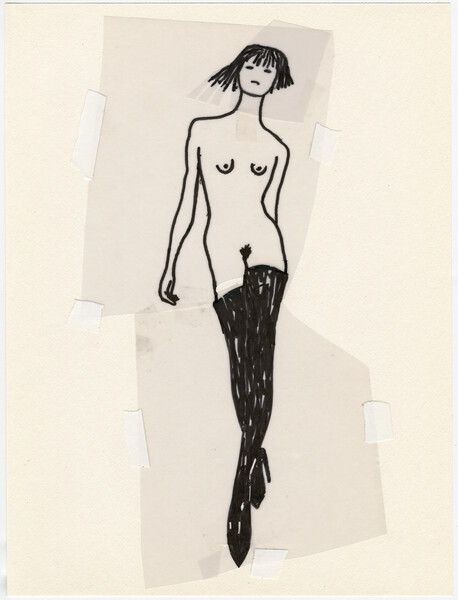

Ida Applebroog, The Ethics of Desire (Studies), 2012. Photo: Emily Poole. Courtesy the artist © Ida Applebroog

"There are all kinds of feminisms. I hate to say ‘I’m a feminist, that one’s not a feminist, or that one could hardly be called a feminist.’"

RK: Some of the pieces from those years that you’ve shown me pictures of seem to be covered in plastic wrap and look like cocoons. Later you started using the clear coating of Rhoplex, on top of vellum, to create a shiny, skin-like surface that became one of your trademarks. Were you drawn early on to that kind of shiny effect?

IA: No, it wasn’t about shiny stuff. The plastic wrap was to get it to look like a cocoon but for you still to be able to see the material under the plastic, like a mummy. It was just practical. That’s what I found, and that did the trick. Those were the ones that Robert Hughes destroyed.

RK: The art critic Robert Hughes? How? Why?

IA: The sculptures had gone to New York and were being kept in a storage place by the dealer Max Hutchinson, who was also an Australian, like Hughes. They were friends. Hughes saw the pieces hanging there and decided they looked like punching bags and that he would punch them out. And he punched them to nothing.

RK: He wrecked them completely?

IA: Destroyed. He was the first destroyer of those pieces. And I never had the guts to do something about it. I was too frightened. I mean, he was such a big name. How do I go against someone like Robert Hughes? I met him later on in San Diego; he did a lecture there. I didn’t have the guts to go over to him and say, ‘You fucking shit! What did you do?’ Nothing. He offered me a ride on his motorcycle, and I didn’t even want to get close to him. Those were my two encounters with Robert Hughes.

RK: And then later, after you came back to New York in 1974, you destroyed all of the rest of that work yourself because you felt it looked too much like Hesse?

IA: A curator at P.S. 1 [now known as MoMA PS1, in Queens] said that he thought I was ripping off Hesse. I think that was what made the decision. So when the garbage men came the following morning, I just wrapped them up in black plastic bags—bagged them up and threw them away, little by little, over a couple of weeks.

RK: And you saved none of it?

IA: No.

RK: Looking back, do you ever regret that, or do you think it had to be done?

IA: It had to be done because that’s who I was at the time. Every step of the way, that’s who I was.

RK: At what point did the women’s movement and feminism become a part of your life? Was that in Chicago?

IA: Oh, not at all. Didn’t have a clue. That happened in California. As far as I was concerned before, that was life. It never even occurred to me that there was anything wrong. I mean, I knew there was a lot wrong, personally, but it never occurred to me it was something I could do anything about. It was only later on that I read Betty Friedan. It was like this whole world suddenly opened and, ‘Oh really? Oh my God. Really? Yes, really.’ That’s pretty much how my world opened up, very slowly.

RK: How did you come to be involved in Heresies?

IA: It was Lucy Lippard and Miriam Schapiro and Joan Braderman, Joyce Kozloff, I can’t remember all the names…Pat Steir, Joan Snyder. It was a large group of women, and they were just starting the issue, and they asked me if I wanted to be part of it. It was better than winning the MacArthur. I remember it really saved my life.’ I was involved, with Pat Steir and others, in making the second issue. I got a lot of women, like Louise Bourgeois, Annette Messager, and others I thought did some interesting work and were funny. They were not deadly serious. Instead, they were funny at being deadly serious. And the thing is, there are all kinds of feminisms. I hate to say, ‘I’m a feminist, that one’s not a feminist, or that one could hardly be called a feminist.’ There are all kinds, and that was from the very early wave of the ’70s. As it went on, it changed, and that was good. There are beautiful characters now like Harvey Weinstein and our dear President Trump, dare I say his name. So how else can you be but feminist nowadays?

RK: This is when you’re already back in New York. Did you have a gallery then?

IA: I had no idea about how to get a gallery. I began making the books [small self-published books based on Applebroog’s drawings of characters in ambiguous, often deeply unsettling situations, framed as if by a proscenium or a window]. I made a mailing list, of writers and artists I knew or liked until it was finally at 500 people. And I’d take all the books in a shopping cart to the Canal Street post office and mail them in bulk. Cost me very, very little. There are a lot of people who have them still. And there were people who wrote back and said, ‘Who are you!? Don’t ever send me anything like that again.’ I kept all the responses. I thought the books were reasonable, myself. I thought they were kind of funny, too. In fact, I even had a little fantasy and sent some out to The New Yorker. I thought they would make nice New Yorker cartoons. I got a very polite response saying, "Thank you, but no thank you."

RK: Maybe we should talk about the work you’re doing now, which you’re calling Angry Birds of America. When did the fascination with birds begin in your work?

IA: I do love birds. I will admit to you that I used to go to country auctions and get taxidermy birds. Nobody really wanted them except me because they’re a little creepy. But I used to collect them for two dollars, five dollars, and I have a huge collection. I started to read up on Audubon, and then read the history of ornithology.

RK: Did the impulse for this work start out with the idea of actually drawing from nature, birds, out in trees.

IA: I would have loved to, but I don’t think I’m capable of doing that any longer. Besides, it was just stupid on my part to think that somebody could actually do that, because birds fly, they’re all over the place. You have to shoot the bird first, of course, and then sling it, put it into different positions that you want, put it on a pedestal. That’s the way ornithologists did it. The birds were all killed. They were dead. We started painting birds and making little birds with plaster, painted like these. [As we spoke, Applebroog, with the help of her assistants Robert MacDonald, Emily Poole and Andrew Coppola, was painting and sanding hundreds of white plaster bird sculptures, basing them on birds in ornithological books piled around her.] I started calling them Angry Birds of America. It was just something that stuck in my head. And then I realized I was in the middle of the Trump era. There was a lot of anger, not just me, but all over America. My feeling was, whatever I was doing, it had to do with angry, dead birds. For whatever it’s worth, I feel like I’m living in a world where we’re all very, very angry. And I know there’s a game called Angry Birds.

RK: I have it on my phone. My kids make fun of me for still playing it. They’re like, "That’s a really old game, Dad."

IA: I don’t know it at all, but the title just stuck in my head. They’re going to kick this president out of office. They’re going to find out about his money and all the terrible things he’s done in the past. I would love it to happen, but I’m not too sure that I will live to see it happen.

RK: You’ve got a lot of birds to go here.

IA: There are. I like doing this a lot. Painting of any kind is always a pleasurable activity.