Films

Serious Play

Musa Mayer on the work of Philip Guston

- 17 May 2024

- Philip Guston: Serious Play (2024), produced by Hauser & Wirth and The Guston Foundation

- Related Artist

- Philip Guston

In a new film presented by Ursula, Musa Mayer takes us through the life and work of her father, the artist Philip Guston, whose variation in style over the years embodies his belief in the importance of learning to have the capacity to change, and his willingness to engage in the “serious play, which we call art” that “can’t be static.”

Born in Montreal, Canada, in 1913 to poor Russian Jewish émigrés, Guston moved with his family to California in 1919. Briefly attending the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles in 1930, he was otherwise completely self-taught.

Guston’s first precocious work, Mother and Child, was completed when he was only seventeen years of age. Influenced by the social and political landscape of the 1930s, his earliest works evoked the stylized forms of Giorgio de Chirico and Pablo Picasso, social realist motifs of the Mexican muralists, and classical properties of Italian Renaissance frescoes of Piero della Francesca and Masaccio that he had seen only in reproduction. Painted in Mexico with another young artist, the huge fresco The Struggle Against War and Fascism drew national attention in the US. Guston’s success continued in the WPA, a Depression-era government program that commissioned American artists to create murals in public buildings. While not widely known today, the young artist’s early experiences as a mural painter allowed a development of narrative and scale that he would draw upon in his late figurative work.

Philip Guston, Mother and Child, 1930 © The Estate of Philip Guston. Promised gift of Musa Guston Mayer to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Philip Guston, The Struggle Against War and Fascism, Museo Regional Michoacano, Morelia, Mexico, 1934 – 35 © The Estate of Philip Guston

“If I speak of having a subject to paint, I mean there is a forgotten place of beings and things which I need to remember. I want to see this place.”—Philip Guston

In the early 1940s, as the WPA program was ending, Guston found work teaching at universities in the Midwestern United States. In his studio, he was working in oils on easel paintings that were more personal and smaller in scale, focusing on portraits and allegories, like Martial Memory and If This Be Not I. His first solo exhibition in Iowa was well received and, within a few years, he was offered his first solo show in New York City. Guston was awarded a Prix de Rome, allowing him to leave teaching and spend a year in Italy, studying firsthand the Italian masters he loved.

By the time he had finished The Tormentors, Guston’s move to abstraction was all but complete. On his return from Italy, he continued dividing his time between the artists’ colony of Woodstock in Upstate New York and New York City, which was then emerging as the center of the postwar art world. He rented a studio on 10th Street, where abstract expressionists Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko also worked.

Philip Guston, Martial Memory, 1941 © The Estate of Philip Guston. St Louis Art Museum, St Louis, MO

Philip Guston, If This Be Not I, 1945 © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy of Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

Philip Guston, The Tormentors, 1947 – 48 © The Estate of Philip Guston. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco CA

Guston’s abstract paintings and drawings were anchored in a new spontaneity, freedom and intense engagement with the act of creation itself. In the early 1950s, Guston’s atmospheric abstractions invited superficial comparisons with Monet, in works like Painting, but as the decade progressed, he worked with heavier impasto and brooding colors, as in Native’s Return.

His paintings of the next several years were darker, more anxious and gestural in nature. This increasingly somber work was influenced by European writing and existential philosophy, particularly the works of Søren Kierkegaard, Franz Kafka and Jean-Paul Sartre. Guston was among those who left the Sidney Janis Gallery in 1962 in protest over the Pop Art exhibition the gallery mounted and the shift towards the commercialization of art that this represented. His reputation continued to grow, however, culminating in his first major retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1962.

Philip Guston, Painting, 1954 © The Estate of Philip Guston. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Philip Johnson Fund

Philip Guston, Native's Return, 1957 © The Estate of Philip Guston. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C., Acquired 1958

For Guston, success was never what mattered most. He was already impatient with the language of pure abstraction and experimenting with larger forms, using a limited palette of grays, pinks and blacks. As his forms became still more reduced, he stopped painting altogether and embarked on a series of simplified abstract “pure drawings” in brush or charcoal. At this juncture, Guston removed himself from the art scene in New York, living and working in Woodstock for the remainder of his life.

Guston’s move was hardly a withdrawal. Freed from the distractions and formal constraints of the art world and the opinions of critics, he was able to experiment with new forms and to engage more deeply with the issues that mattered to him.

The 1960s was a period of great social upheaval in the United States, characterized by assassinations and violence, civil rights and anti-war protests. “When the 1960s came along I was feeling split, schizophrenic,” Guston later said. “The war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?”

Philip Guston, Untitled, 1968 – 69 © The Estate of Philip Guston

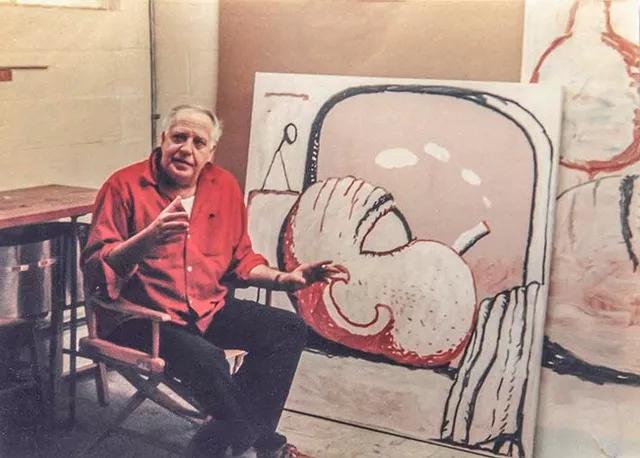

Guston with Smoking I, painted in 1973. Photo: Barbara Sproul

“This serious play, which we call art, can’t be static … you have to keep learning how to play in new ways all the time. It’s always good for the first time, and then somehow, that has to be recaptured constantly.”—Philip Guston

By 1968, Guston had abandoned abstraction altogether, rediscovering the narrative power he had known as a young man in his murals and early figurative works, newly informed by a painterly sensibility forged in abstraction. This liberation led to the most productive period of his creative life.

He began by exploring ordinary objects, developing a personal lexicon of light bulbs, books, clocks, cities, nails in wood, cigarettes and shoes. In the larger works that followed, he introduced surreal motifs, peopling his new world with strange, hooded figures in cartoonish form. In part, they were related to the Ku Klux Klan, an American white supremacist group with a long history of lynching and racial violence. Not only evil, but also vulnerable and even humorous, the hoods can also be seen to represent the masks we wear in public, the contradictions of human nature and the artist himself, as in The Studio.

Philip Guston, The Studio, 1969 © The Estate of Philip Guston. Promised gift of Musa Guston Mayer to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

By 1972, the hoods were off. Guston’s expressively rendered, painterly work of his last decade became more overtly autobiographical in nature, featuring the recurring reclining figure of the artist as a hood or bean-like head with an enormous open eye. There were tender portraits of him with his wife Musa, like Couple in Bed and Source.

Philip Guston, Couple in Bed, 1977 © The Estate of Philip Guston. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago IL

Philip Guston, Source, 1976 © The Estate of Philip Guston. The Museum of Modern Art, New York NY

Motivated by internal forces, Guston’s last works possessed a mounting freedom, unique among the artists of his generation. By the mid-1970s, the strange iconic forms emerging from the paintings were unlike anything previously seen in art. “If I speak of having a subject to paint,” Guston wrote in a studio note, “I mean there is a forgotten place of beings and things, which I need to remember. I want to see this place. I paint what I want to see.” As in the early murals, allegories of horror and war are evident, for example, in Pit. But all is not bleak; the works contain humor, pathos, even transcendence, as in The Line.

Philip Guston, Pit, 1976 © The Estate of Philip Guston. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Philip Guston, The Line, 1978. Promised gift of Musa Guston Mayer to The Metropolitan Museum of Art © The Estate of Philip Guston. Private Collection. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Guston’s late figurative paintings were rejected by the art world when first shown in 1970. Despite the growing excitement of younger painters, the art of his last years remained largely misunderstood until after his death in 1980.

An inspiring teacher, Guston often talked to his students about how crucial an approach of doubt and self-questioning was to his creative process, wherever it might lead. “Some of you may wonder, why all these changes,” he told a group of art students, “It’s taken me many years, but I’ve come to the conclusion that the only ‘technique’ one can really learn is the capacity to be able to change.”

Guston’s work underwent a radical reappraisal following a traveling retrospective that opened three weeks before his death, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Other retrospective and solo exhibitions in the United States, Europe and Australia have followed in the ensuing years. Today, Philip Guston’s paintings and drawings are considered among the most important art of the twentieth century.

Guston in his studio, 1980. Photo: Sidney Felsen, Gemini G.E.L.

-

“Philip Guston: Singularities” opens June 7 and continues through September 7 at Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse.