Ellen Gallagher at Tate Modern reviewed by Frieze

Installation view, 'AxME', Tate Modern, London, England, 2013 © Ellen Gallagher. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Ellen Gallagher at Tate Modern reviewed by Frieze

There’s a certain thematic polyphony to Ellen Gallagher’s work, leaping, as it does, from Atlantean creation myths to Afrofuturism, psychoanalysis and post-Minimalism, which has led some commentators searching for musical analogies to compare it to jazz – the Scottish poet Jackie Kay likened a piece of Gallagher’s to ‘jazz on a canvas.’

But this reference, as well as the affinity that Gallagher’s work is said to have with the music of defunct Detroit techno duo Drexciya, actually misdirects attention. Follow the jazz line and you walk backwards along a well-trodden hermeneutical path, through post-black identity politics to the Harlem Renaissance. And while it’s true that Gallagher has used Drexciya’s namesake and the band’s narrative of a black Atlantis, peopled by slaves drowned during the Middle Passage, as inspiration for her own oceanic myth, their actual music – evoking a Kraftwerkian world of post-industrial paranoia, alienation and existential parody – also leads to another impasse miles from the organic, briny mysticism of her art.

‘AxME,’ Gallagher’s serious and significantly sized mid-career retrospective at Tate Modern, shows that her works do have contemporary musical affinities of new interpretative worth, but they are with the tape-worn aural landscapes of Boards of Canada, Gonjasufi, Oneohtrix Point Never, and recently Portishead. This cadre of musicians is engaged in compositional work that some have called hauntology – a term borrowed from Jacques Derrida’s ‘Spectres of Marx’ (1993) and used by writers including Simon Reynolds to refer to music in which analogue synthesizers and tape effects evoke a hazy period, falling across the 1960s and ’70s.

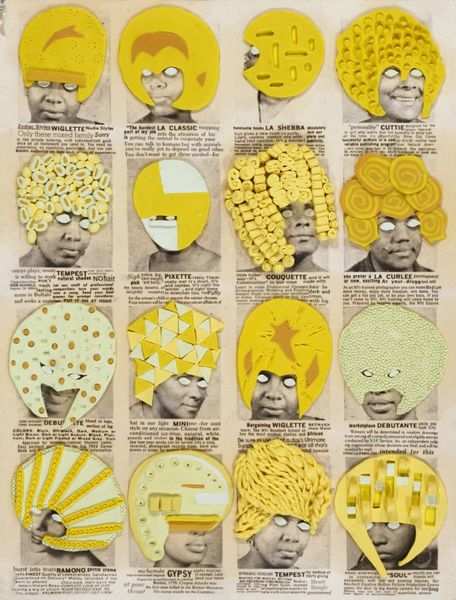

In the hauntologists’ use and evocation of old-media, there is a distinct sense that something otherworldly, numinous and transcendent is being reached for. Gallagher’s work compounds this in its use of critical strategies of temporal disruption, time-travel and archival interrogation: ‘Odalisque’ (2005) appropriates a 1928 photograph of Henri Matisse sketching an ‘exotic’ model, replacing Matisse’s head with Sigmund Freud’s and the model with Gallagher’s own; ‘Deluxe’ (2004–05) détournes 60 pages from midcentury African-American magazines.

In this way the work’s act of excavation shifts from apolitical retrospection to the disruption of what American queer theorist Elizabeth Freeman calls chrononormativity – her term for a conception of time used to propagate normative heterosexuality, monoculture, capitalist production and its rhetoric of unrelenting technological progress.

Ellen Gallagher, DeLuxe (Detail),’ 2005 © Ellen Gallagher

Gallagher, who lives between Rotterdam and her native New York, came to prominence during the 1990s, at a time when artists including Glenn Ligon and Kara Walker were dismantling legacies of slavery and segregation as filtered through the channels of US pop-culture and folklore. An example of her work during that period is ‘Oh! Susanna’ (1993), a painting in which Gallagher uses the disembodied iconography of minstrelsy to create an abstract surface of small circles, dots and curves.

Since then, the assimilation and marketization of the ’90s generation’s rhetoric, and the transformation of political signifiers into benign genre-specific tropes – the presence of afros, copies of Ebony or Jet magazines, references to hiphop and so on – has blunted some of their bite, not to mention that of some ‘post-black’ successors like Rashid Johnson and Kehinde Wiley.

But by offering something else, by giving the viewer a credible, secular experience of mystery and spirituality, through art works that formalize aspects of a compelling myth, Gallagher shows a way past not only that condition, but through two enduring pre-millennial cultural deadlocks: the lazy essentialism implicit in interpretations of so-called African-American art, and the pervasive intellectual paralytic of a contemporary artistic sensibility whose main features are irony, remixology and materialism.

To find one of the most effective executions of this boundary-leaping, you have to fast-forward through ‘AxME’ to an extraordinary installation titled ‘Osedax’ (2010). Made in collaboration with Dutch artist Edgar Cleijne, the work features 16mm film and painted glass-plate slides projected inside a large black box. A colourful mix of marbled ink abstractions, the slides dissolve into one another to create a hypnotic sense of morphogenesis.

The film’s contents, soundtracked by a mesmerically low-slung funk loop, are a series of fragmented scenes suggesting a narrative of transformation: a shipwreck, a sea creature’s underwater journey, an oil rig at night, floating striae resolving into human faces. Both ‘Osedax ‘and ‘Murmur’ (2003–04), another collaborative installation of five 16mm films made with Cleijne, contain startlingly innovative film work.

Of course, many artists are using the sumptuous quality (not to mention the suggestion of documentary objectivity) that celluloid brings, to create works which hover between archival truth, myth and memory. But by combining film with computer animation, using celluloid in conjunction with the medium responsible for its obsolescence, Gallagher and Cleijne also create moments of startling three-dimensionality – the rotating fish in ‘Kabuki Death Dance’ (2003), for instance.

The results are a stunning showcase of film’s distinct, almost supernatural ability to depict sculptural depth, the likes of which I haven’t seen since German computer artist Manfred Mohr’s luminously tangible ‘Cubic Limit’ (1973–4). The retrospective’s comprehensive, if slightly long, 11-room display presents the two halves of Gallagher’s practice: the deft early contributions to critical discourses of identity politics and race, and her steady progression into rich territories of thalassic mystery. While the former are important threads within the network of socio-cultural strands her works seek to embody and interrogate, it is Gallagher’s engagement with myth through sound, film, painting and drawing that is heading for strange new ground.

Related News

1 / 5