Rita Ackermann Interviewed by Josh Smith

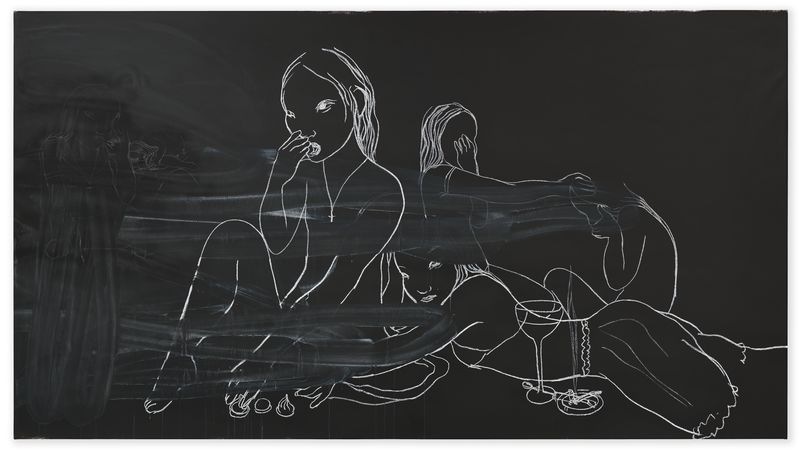

Rita Ackermann, 'Wiped Out Heroines', 2014

Rita Ackermann Interviewed by Josh Smith

On the heels of her recent solo exhibition at Hauser & Wirth in New York City, we invited Hungarian-born painter Rita Ackermann to record a conversation with an artist of her choice.

She decided to continue her ongoing dialogue with painter Josh Smith. Both were making drawings on paper while they recorded a chat about studio practice, exhibiting, and communicating through their work. (Sounds of scraping and rubbing on paper.)

Rita Ackermann: Here’s a question for you, Josh. Do you feel offended when your work is called “literal” or “storytelling”?

Josh Smith: No, I’m not offended.

RA: I’m a bit skeptical about painting that tells a story or is too literal. Do you want to tell a story with your work?

JS: Well, I know that if I make my work properly it will make a story. I think that my work is successful when you can tell everything about it by looking at it. If you have to ask a question or hear from somebody else what my work means, then maybe I’m not doing a good enough job.

RA: So you want the work to deliver something to the person who is looking at it?

JS: I want it to be complete in a way. Regardless of what viewers might know about me, or art, there’s still something there for them. They can see how the painting was made and feel comfort in understanding that I wasn’t trying to play some kind of trick on them.

RA: Yeah, so it would give something to the viewer—whatever they want to receive from it, right?

JS: Yes. They can put themselves into it for a moment, and if they don’t like it they can walk away. They can just take it or leave it.

RA: Or, if they find it funny, they can laugh about it. When your painting comes through funny, do you like that?

JS: Well, there are all sorts of laughter. I don’t know…. But this interview is supposed to be about you not me. Why did you ask me to talk to you, and why are you asking me questions?

RA: I wanted to talk to you because you say fundamental things about painting and art that I agree with. And I know that you can say them accurately and articulately and with the right vocabulary. I fear that when I speak, it doesn’t add to but takes away from my work. I don’t like to speak about my painting. I prefer to just do it.

JS: Plus I’m your neighbor.

RA: Plus we have known each other for a long time. You respect my work, and I respect your work. We have nothing to hide from each other and it is okay to speak our minds even through rambling sometimes.

JS: Contemporary art is a tough thing to like.

RA: I think a lot about humor in art. I don’t want to make humorous works, but they can end up funny anyway. Like the junkie figures in my early paintings or your grim reapers. They are twisted characters that end up being comical. And sometimes there is the intention to be funny, but it turns out not funny at all.

JS: The subjects I’m known for in my work are humorous. Like painting my name is humorous. As is painting my color palette, which ends up being an abstract painting. These are all funny, perpendicular types of images that cause a person to hit a wall. The viewer has to make a decision: Are they going to laugh or get angry at it? Or just accept it? I mean, when I say the viewer, I also am referring to myself.

RA: You are the number-one viewer, I guess.

JS: I’m the first one. But people’s opinions are part of the reward. To even get an opinion, you have to know people and be in the world. I like opinions, negative or positive. RA It’s good, yeah. Getting a bad review can be helpful—if it addresses the work not the person. The next day in the studio, I think about what a person sees in my picture that I can’t see for myself. I would not have let the painting leave the studio if it wasn’t completely resolved for me. So returning to my work after a review gives me a new perspective because before I couldn’t see what someone else saw. I can only paint my own emotions, but how the work is perceived by the public also belongs to the painting. Do you ever fear your paintings will be misunderstood?

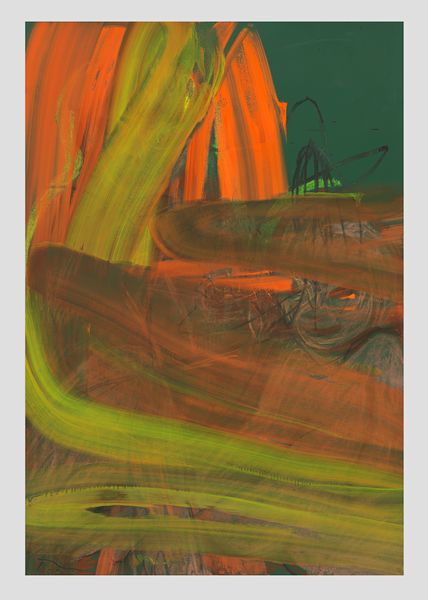

Rita Ackermann, 'Stretcher Bar Painting 4', 2015 © Rita Ackermann. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Rita Ackermann, 'Neverland', 2015 © Rita Ackermann. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

JS: It’s someone’s opinion. There are cases of extreme prejudice where the person is just never going to give you a chance, and there’s a theater to that, which I appreciate. There are critics who will give you bad reviews no matter what. And you can’t do anything about it. In Donald Judd’s reviews of his contemporaries he described what he saw and then passed judgment based on his perspective and what he felt the potential of the situation to be and whether or not the artist took advantage of it. Those reviews are not right or wrong. I love reading them.

RA: There was a more fearless “open-fire” attitude in the art world then. People weren’t as scared of saying what they were actually thinking.

JS: Yeah, that’s over. (laughter) You can’t criticize anything, right? I mean these people didn’t have to contend with the Internet. You either went out and you were in the world, or you stayed home and did nothing. Now people can stay home and still be assholes and hurt people.

RA: Behind a screen people are a lot more aggressive and daring than they would be face-to-face. The Internet allows people to say as much ignorant stuff as they want because they are safe and shielded from direct reactions.

JS: You don’t even have to come see the show, you can just write nasty things without leaving your house.

RA: I got a brief but condescending review for my last show at Hauser & Wirth days before the show was even installed. I wondered how the guy reviewed the show before the installation even happened. But then I realized he just went on the gallery website and looked at a few random images, some of which were not even included in the exhibition, and wrote a review of the show that he hadn’t seen. He already knew what he was going to say.

JS: What’s the next question?

RA: Right now you’re working on a show in Norway opening in March and you’re in the middle of completing a series. Does it make you anxious how time grows shorter till the moment when the paintings must go?

JS: I always wish I could spend more time on things. But you can’t. There is a performative aspect to being a contemporary artist. You have to do the show.

RA: I feel that pressure, too, but sometimes that rush helps me finish works that I would otherwise be sitting with for months. My last show in New York fell on me from the sky. The gallery asked me to do it three weeks before the exhibition opened. They were confident that I could do the show with the work I had accumulated over the last two years. I was grateful for the urgency of the exhibition because if nobody had taken the paintings away at a certain point, I would have just overpainted every one of them.

JS: I would paint over everything, too.

Kline Rape III, 2016 © Rita Ackermann. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

RA: But sometimes it’s not good for the series. That’s a dilemma for me—when I’m presenting a subject, I feel every step is significant. When you overpaint your work, you’re covering up your studies and you lose the freshness of it. Looking at art history, sometimes I find the studies more compelling than the final picture. If you overpaint your work, you will never find out if a certain study had everything you’ve got as a painter. Although you can document each step you can’t copy freshness or urgency. You can’t copy yourself.

JS: When you’re working over another painting it’s different than working on a fresh canvas. It’s thicker and you can see that. In the Picabia show that’s up at MoMA now, you can see there was a period when he was overpainting everything. The paintings are crustier and they’re not bad at all, they’re still great Picabias. Rather than giving the world tons of Picabias, he was just keeping them.

RA: He took back his entire unsold show from Chicago and overpainted every painting. He was frustrated, no? He was embarrassed by the financial failure even though he probably didn’t depend on his sales. He was brutally self-critical and hard on his work. He just took the works back and overpainted them. He was the Godfather of destroying paintings. With the cheap pinup porn aesthetic, he was giving the middle finger to the audience, to his peers, and to himself. But then there are his transparent paintings. Those are my favorites.

JS: There was no outlet. Also, he worked during the war; it was a different situation. If you look at a Picasso, you can see the lightness. Picasso was not someone who painted things over very often. He only did that in the beginning.

RA: Picasso was so free. He allowed his mind to work the same way a child plays. If someone doesn’t have the skills or classical training to fall back upon, this childlike freedom can be risky and misunderstood. You can’t break the rules without knowing them. I believe in classical training. Those years of consistent studio practice provided me with a foundation to experiment with different forms of expression.

JS: I’ve seen people who are not really painters—they are not even artists—they just think about things. And then they are offered a show and make a bunch of works and suddenly become artists.

RA: That could be good. I feel everybody should get a chance to be an artist and have an opportunity to show their work. But then there comes a time when you can’t depend on others’ opinions and you’re alone with only yours. You need time with your doubts and self-reflections to truly grow. That’s when you realize whether you really want to be part of this game. I heard an artist say, “When I’m painting, I know what I am doing, but I don’t know what I am making.” What do you think of that?

JS: I agree with “I don’t know what I’m making.”

RA: It makes sense, right? There is some logic there if you want to listen to what the painting has to say in the process of making. It’s like trying to fix a problem or tame a wild horse: you don’t know where it is going to take you or how long it will take to finish. There must be things you want to control, though. For instance, I like to limit the palette for a series. JS I have confidence in what I do. I know it will work out. I mean, I can sound as arrogant as you want me to about that stuff. I feel like the canvases are kind of finished when I get them, when they’re blank. I’m just messing them up from the very beginning, so in that respect, it’s a complicated situation. We all know that a gallery full of white canvases done properly can look pretty good. I did a show like that in Japan. It looked good, but you have that problem where you know that you’re hurting the thing.

RA: How do you hurt the perfect canvas?

JS: You hurt it in the best way. You touch it a few times with your brush, here or there. And it’s done.

RA: You paint what you want to see.

JS: That’s where an idea would come in, and ideas are stupid. I have tons of ideas, and I’ll give them away because they don’t have any value to me. Like, what can I do with red and black? What can I do with this American landscape thing or with this traditional printing technique—make a problem and then solve it on the canvas.

RA: Fixing the ideas on the canvas. How much do we need ideas at all? Like what if you don’t have any ideas? What happens then?

JS: In periods when I don’t have anything I urgently want to make, I usually just learn something—like ceramics, woodworking, or glass enameling. It’s something I do as a distraction but a lot of times something comes out of that.

RA: What do you distract yourself from?

JS: Finishing my paintings.

RA: (laughter) Really? Why do you need the distraction from finishing?

JS: Because I don’t want to kill the thing. I just let it live in my studio, while I screw around with something else or just read.

RA: It’s true that there is much waiting time in the studio. If you can’t sit still and just keep looking, you must find a side activity to distract yourself or you might overpaint things that should have been left alone, right? This is the reason I usually work on two completely different bodies of work. I can bounce back and forth between the two of them. It’s also easier to take a step back from each painting. Sometimes there are three different series of works growing simultaneously in my studio.

JS: The paintings I’m working on now, I did them over a year ago and then I left them. Now they don’t seem fresh enough for me, so I’m putting them through the machine again. There’s a new thing on an old thing.

RA: There can be freshness in old work. Pulling out a painting I made a year ago, I might notice what is missing and suddenly feel inspired. Then I can sense better what it needs to be complete. (Rustling papers. Looking at drawings.) These drawings are getting silly. I’ve got this funny horse going here, because I know you’re making horses. This horse is acting like a human.

JS: I love drawing horses. They are really nice to make.

RA: Horses are hard to draw, especially when you draw them off the top of your head.

JS: Yeah, but if you just make the legs long and put a tail and a mane on it, then everyone knows what it is.

RA: Except the horse has such a strange forehead. When you make it wrong, it looks like a dog.

JS: I’m very curious about the different ways to make something nice in two dimensions. That’s what I am fascinated by: looking at images and books and just seeing what makes pictures function.

RA: Almost all my paintings are about movement—forms or figures moving in and out of dimensions of depth within a rectangle. They are like a wild dancer. Lines can become the traces of movements. For example, when I make the chalkboard paintings, the physical effort of erasing is recorded. Painting for me is physical work. There are patterns of movements that I’m not aware of while I’m working, but I can see them clearly later when I step back to look at what I’ve done. With the chalkboard paintings the movements are uninterrupted to show the gestures from the washes moving as a large flow.

JS: And when you bring in color, a whole other challenge evolves.

RA: Yeah, the line is already problematic enough. Line is always harsh news in space. It cuts and separates forms and demands all the attention. It’s the same with the eye on a face; you can’t help but keep looking at the eye. Overall a painting is like the body. Your paintings have the size of a human body.

JS: I can paint best at that size. I can lift my canvas. The size fits me perfectly.

RA: This last year or two I have mostly painted in body-size proportions. It was good to be able to pick up the painting and move it around in my studio.

JS: Some people like to have assistants.

RA: I like to make all the decisions myself. I might be too controlling. Sometimes I think it would be nice to work with many assistants, with a whole team taking part in making decisions. You can ask them questions like, How should the work look? Do you think it should be pink there or blue? Should I make another one in yellow? What do you think, guys? And the team can truly participate in making the work. That’s a generous way of working. I might be very selfish not giving anybody else a chance to participate.

JS: I don’t think there’s anybody who knows anything about what I’m doing. Even the people I know the best don’t know. My dearest, closest friends don’t know.

RA: On that I agree and disagree. It depends how we look at the question of knowing. I mean, there is always “Only God knows what I am doing… “ Do you ever think contemporary art can be spiritual? I think it is awfully hard to talk about the spiritual meaning of paintings today.

JS: As close as I can get to being spiritual is being honest.

RA: I like that and completely agree. Honesty is the only thing we can reach and rely on. Beyond that is the ineffable, which could be anything.

JS: I hope that my work continues to grow more simplified. I always wish for my work to organize itself more somehow.

RA: I have this idea that before I die, I would like to plan out my own survey exhibitions, and lay down some suggestions for different groupings of works. I play out different shows in my head and get really excited about organizing and relating works regardless of when they were made. I don’t believe in chronological surveys—you can group works by certain themes that make an exhibition flow.

Rita Ackermann, 'Meditation on Violence IV', 2014 © Rita Ackermann. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

JS: I’m not thinking about dying yet. I mean, if I died now it would be a big mess. But I don’t care so much. I hate when the whole of my work feels overwhelming. I take it one thing at a time. I like being an artist, I like the opportunities I get and the people I meet. I appreciate the community that being an artist provides. I love people.

RA: You love people as much as you are a recluse.

JS: They interfere with the privacy that you need to be a good artist, but I think people are so colorful and hilarious and beautiful.

RA: Do you do your work for the people?

JS: I work so I can have something to share. I need some currency to be around the special people I like. The currency I have is my art. If I didn’t have that, I’d have to rely on something else exceptional to collect such interesting company.

RA: Do you use your work as a form of communication?

JS: I do. The work allows people to see another side of me. For you, too, I believe. It centers you; it gives you a kind of solid currency. It’s like money.

RA: I agree with you. My art is the only hard currency I can offer the world. I can make a picture and I hope it can touch someone deeply, make someone think and feel differently.

JS: It’s lucky to find something like that to be happy in life. It doesn’t have to be art, but you can interact with others and laugh about things. What people end up doing in the real world is they have kids. And they sit around and talk about their kids with other people with kids. But we don’t have kids. I mean, you do, but your kid is an adult now. So art is kind of like our kids. Then the kids go away, and you don’t see them for a while. It’s a bad analogy, a sort of pathetic replacement.

RA: The work we make is our family. It can be unsettling to look back at how many different paintings I’ve made. But they all come from the same core. There’s an energy that moves through them that is my very own but that I don’t possess. I want these paintings to live happily ever after. Josh Smith is a Brooklyn-based artist. He has had solo exhibitions at Bonner Kunstverein, the Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome, the Brant Foundation, the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, and MUMOK, Vienna.

Related News

1 / 5