Alexander Calder / David Smith

10 June - 16 September 2017

Zürich

To coincide with Art Basel 2017, Hauser & Wirth Zürich presents an exhibition uniting two great figures of 20th- century American sculpture: Alexander Calder (1898 – 1976) and David Smith (1906 – 1965). Realised in close collaboration with both the Calder Foundation and The Estate of David Smith, ‘Alexander Calder / David Smith’ explores the artists’ mutual resolution to test the limitations of traditional sculpture and redefine the parameters of abstraction in three dimensions. More than the simplified conceptions of the artists – Calder, the ingenious extrovert who commanded the Parisian avant-garde and set the simplicity of abstraction in motion; and Smith, the man of iron isolated on a mountain top, a constructor of enigmatic, wildly diverse ciphers who gave three-dimensional form to the Abstract Expressionist generation – the exhibition, enriched by the dialogue between these two modern masters, sheds light on the deeper complexities of their achievements. The presentation spotlights both intimate and large-scale works across four decades and illuminates how, over the course of their careers, both artists asked many of the same questions that challenged the assumptions of what sculpture could be, but answered them with wildly different solutions in pursuit of their own personal aesthetic identities.

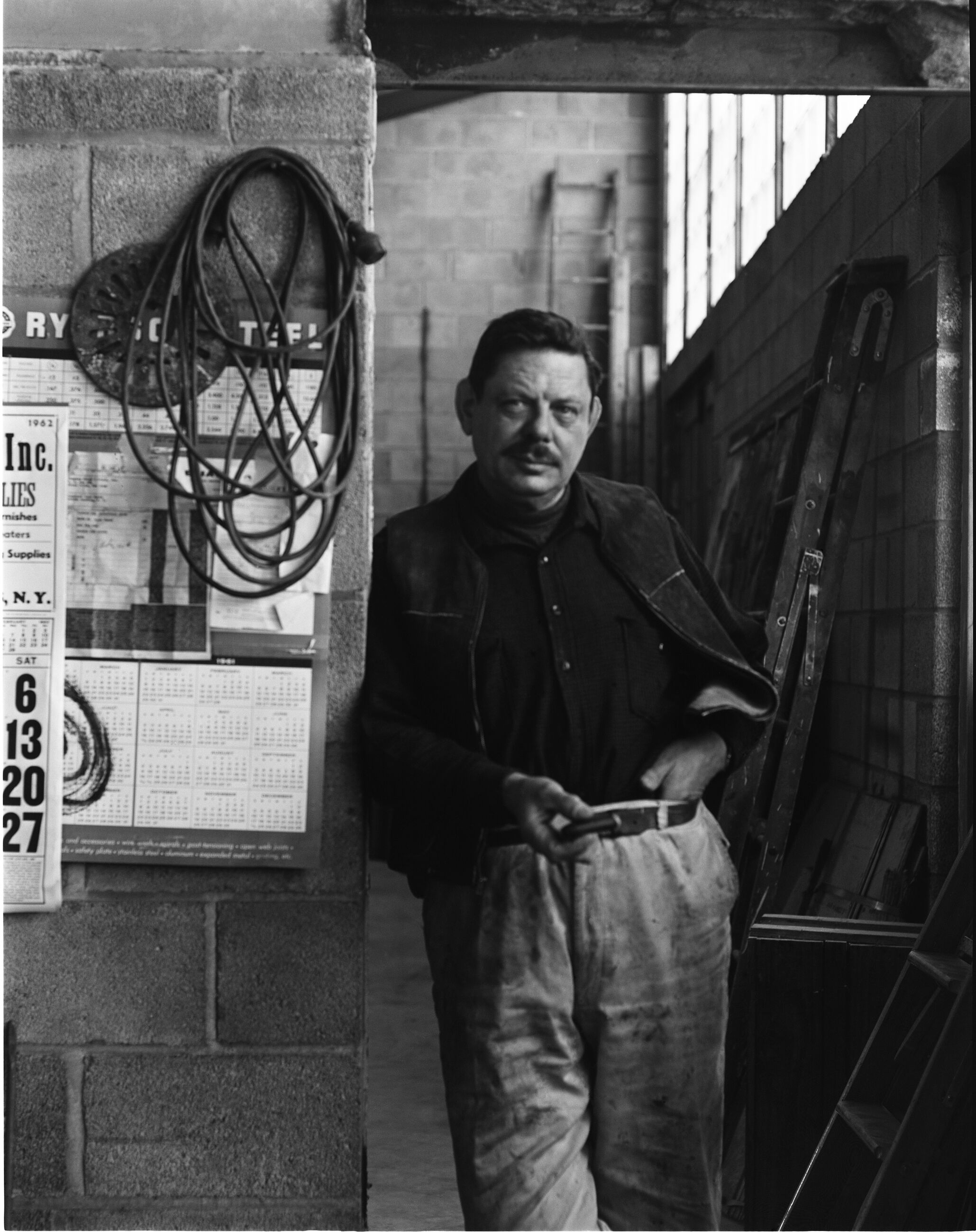

In 1962, both Calder and Smith were invited by the Italian government to participate in the fourth Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto, Italy. Given access to a decommissioned steelworks in the Genoese district of Voltri, the opportunity sparked a creative surge of activity for Smith, resulting in the creation of 27 sculptures in just 30 days, assembled from scrap metal and found objects from the abandoned industrial complex. Calder’s contribution to the festival was ‘Teodelapio’ (1962), a black-painted stabile over 58 feet tall and still in situ today. Exhibited across Spoleto, this was one of the first shows to position the two artists alongside each other. On reflection, this marked a time when both artists were at the peak of their careers having tapped into the tensile strength of industrial metal to create objects so radical and dynamic – that their configurations seemed to verge on the impossible. Since then, Calder and Smith have rarely been exhibited in dialogue with one another.

Both Calder and Smith challenged the assumption that mass was essential to sculpture. They mastered the visual language of painting and drawing – use of line, two-dimensional planes and colour – and, blurring the boundaries between drawing, painting and sculpture, created innovative and spirited new work. The more intimately sized works in the exhibition resonate with the idea of ‘drawing in space,’ a phrase coined by critics in 1929 to describe Calder’s wire sculptures. Calder’s ‘Red Flowers’ (1954) is a hanging mobile in which the artist’s archetypal abstract elements, some perforated, coalesce into an organic composition. Evoking the tradition of floral still-lifes, Calder nonetheless injects his sculpture with motion and a sense of life. Smith’s ‘Swung Forms’ (1937), a delicately balanced composition of welded steel, testifies to Edward Fry’s observation that, ‘Line is used in Smith’s sculpture as in his drawings, as form reduced to its essence, as contour, and as gesture for its own sake’. The curious and elegant work, balancing biomorphic form and linear structure, fuses reference to surrealist content with active gesture that, a decade later, would become the hallmark of the New York School.

Many works, including the large-scale works on view, highlight how both artists used paint to transform the viewer’s perception of three-dimensional objects. Although painted sculpture was not a new concept, it was an unusual practice at a time when ‘truth to materials’ represented the standard. Calder’s standing mobile, ‘Untitled’ (1967) embodies the artist’s approach to colour in his oeuvre, the boldly painted discs of cobalt blue and red demonstrating the harmony that defined his practice. Meanwhile, in ‘Zig I’ (1961), Smith unifies the surface of his monumental, tessellated sculpture with feathery black brushstrokes over russet tones, harnessing the gestural vigour of the artist’s fellow Abstract Expressionists.

While Calder used colour to heighten the disparity in a composition – as seen in two untitled sculptures from 1936 and 1943, which demonstrate the artist’s masterful use of a polychromatic palette executed in intersecting planes – Smith used the painted surface to underline the structural complexity of the sculpture. With its painterly elements of dappled green, ochre, yellow and brown, ‘Untitled’ (1954) emphasises Smith’s commitment to the visual nature of sculpture, and to breaking down the boundary between the media of painting and sculpture. For both artists, the use of paint on metal challenged the viewer to experience their relationship to the sculpture in new and distinct ways.

The work of Calder and Smith also proposed a new relationship between sculpture and the space it inhabits. Using steel and iron they capitalised on the availability and scope of industrial materials to expand the scale and weight of their sculpture, which in turn found its home in both natural and urban landscapes. In creating a new scale for sculpture they encouraged the art form to be viewed in the context of its material surroundings, literally transforming a viewer’s perception of a plaza or hillside. They also insisted that sculpture be more involved with the viewers’ sense of time – sculpture as a performative medium to be physically experienced, not just a static object to be looked at. While Calder’s mobiles are distinguished by their responsiveness to wind and touch, conversely his stabiles and standing mobiles focus on the concept of tensile stress and stability, yet still resonate with energy. ‘Extrême porte à faux III’ (1969) is one such example. Though firmly anchored by a robust black metal base, the long arcing horizontal wire appears insufficient to bear the weight of the mobile elegantly dangling from its tip. It exemplifies tension arcing upwards towards the sky, calling into question the laws of physics while flaunting Calder’s compositional genius. The small suspended mobile is a magical counterpoint so slight that it invites closer inspection to appreciate its brilliance. In Smith’s steel ‘Construction on Star Points’ (1954 – 1956), the gestural vigour and torsion of the geometric constellation evokes a dynamism and sense of upward motion that belies its static nature. With its mix of burnished stainless steel and painted steel, the work is an example of the artist’s notion of sculpture as a multi-faceted image penetrated by space – as the viewer moves around the sculpture, the work continually evolves, with each new angle framing a new image. For both Calder and Smith, sculpture was to be viewed in connection with the surrounding space and the body.

On the occasion of this presentation, Hauser & Wirth Publishers will release ‘Alexander Calder & David Smith’, a new catalogue with texts by Elizabeth Hutton Turner and Sarah Hamill, as well as photographs by Ugo Mulas, who met both sculptors in Spoleto, Italy, in 1962, and continued to document them throughout his life.

Installation views

About the Artists

Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder was born in 1898, the second child of artist parents—his father was a sculptor and his mother a painter. In his mid-twenties, Calder moved to New York City, where he studied at the Art Students League and worked at the ‘National Police Gazette,’ illustrating sporting events and the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Shortly after his move to Paris in 1926, Calder created his ‘Cirque Calder’ (1926–31), a complex and unique body of art. It wasn’t long before his performances of the ‘Cirque’ captured the attention of the Parisian avant-garde.

In 1931, a significant turning point in Calder’s artistic career occurred when he created his first kinetic nonobjective sculpture and gave form to an entirely new type of art. Some of the earliest of these objects moved by motors and were dubbed ‘mobiles’ by Marcel Duchamp—in French, mobile refers to both ‘motion’ and ‘motive.’ Calder soon abandoned the mechanical aspects of these works and developed suspended mobiles that would undulate on their own with the air's currents. In response to Duchamp, Jean Arp named Calder's stationary objects ‘stabiles’ as a means of differentiating them.

Calder returned to live in the United States with his wife, Louisa, in 1933, purchasing a dilapidated farmhouse in the rural town of Roxbury, Connecticut. It was there that he made his first sculptures for the outdoors, installing large-scale standing mobiles among the rolling hills of his property. In 1943, James Johnson Sweeney and Duchamp organized a major retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which catapulted Calder to the forefront of the New York art world and cemented his status as one of the premier American contemporary artists.

In 1953, Calder and Louisa moved back to France, ultimately settling in the small town of Saché in the Indre-et-Loire. Calder shifted his focus to large-scale commissioned works, which would dominate his practice in the last decades of his life. These included such works as ‘Spirale’ (1958) for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris and ‘Flamingo’ (1973) for Chicago’s Federal Center Plaza. Calder died at the age of seventy-eight in 1976, a few weeks after his major retrospective, ‘Calder’s Universe,’ opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

David Smith

David Smith is regarded as one of the most innovative artists and important American sculptors of the 20th century. He transformed sculpture by rejecting the traditional methods of carving and casting in favor of torch-cutting and welding, becoming the first artist known to make welded sculpture in America. These methods allowed him to work in an improvisational manner in creating open and large-scale, abstract sculptures. In his later years, he installed his sculptures in the fields of his home in the Adirondack Mountains, where a dialogue between the art object and nature emerged as central to his practice. His sculpture-filled landscape inspired Storm King Art Center and other sculpture parks throughout the world, as well as anticipating the land and environmental art movements.

Smith was born in 1906 in Decatur, Indiana. He worked briefly as a welder in an automobile factory before moving to New York City to become an artist in 1926. He studied painting at the Art Students league, where Cubism and Surrealism were foundational to his practice. He began welding sculpture around 1933 after seeing reproductions of constructed steel sculptures by Pablo Picasso and Julio González. He later became associated with the abstract expressionist movement and paved the way for minimalism with radically simplified, geometric works. Painting and drawing remained integral to what Smith called his ’work stream’. He embraced a holistic attitude toward artmaking and dismissed the idea of a separation between mediums. Acknowledging the tradition of painted sculpture throughout art history and drawing from the bold palettes of modernism and pop culture, Smith often painted his sculptures. David Smith died in 1965, leaving behind an expansive, complex, and powerful body of work that continues to exert influence upon subsequent generations of artists.

Smith began exhibiting his work as early as 1930. His first survey was organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1957. His sculpture was represented by the United States at the São Paulo Biennale in 1951 and at the Venice Biennale in 1954 and 1958. Posthumous retrospectives have been held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1979 and 2006, which traveled to Tate Modern, London and the Centre Pompidou, Paris) and at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2011, which traveled to the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York and the Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio). Other major surveys have been organized at the Sezon Museum of Art, Tokyo (1994, traveled throughout Japan), the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid (1996), Storm King Art Center (1997–99), and Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, UK. A three-volume, fully illustrated catalogue raisonné of Smith’s sculpture was published in 2021 by the Estate of David Smith and distributed by Yale University Press. A biography by Michael Brenson, David Smith: The Art and Life of a Transformational Sculptor, was published by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux in 2022.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 12