Philip Guston

Laughter in the Dark, Drawings from 1971 & 1975

19 May - 29 July 2017

London

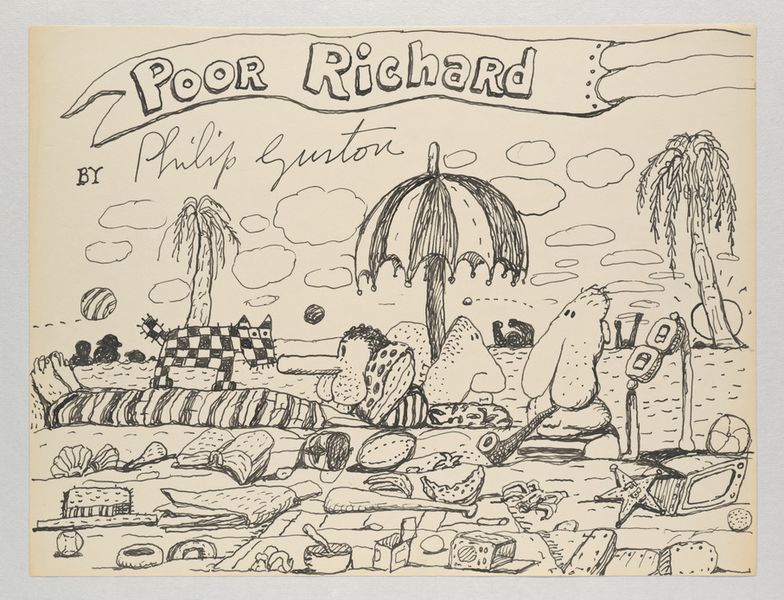

Hauser & Wirth London presents ‘Philip Guston. Laughter in the Dark, Drawings from 1971 & 1975’, an exhibition devoted to the late artist’s satirical drawings of the 37th President of the United States: Richard Nixon. Co-curated by Sally Radic, of The Guston Foundation and Musa Mayer, the artist’s daughter, the show features over 180 works depicting Nixon and his cronies, including Guston’s infamous Poor Richard series and over 100 additional drawings. It is a reconfiguration of the presentation first shown at Hauser & Wirth New York in 2016 and reviewed to great critical acclaim – Apollo magazine: ‘a body of work that has both historic specificity and biting, contemporary relevance’. This marks the first time the entire body of work has been presented together in the UK and is also the artist’s first solo show in London since 2010. The exhibition is accompanied by a book from Hauser & Wirth Publishers that expands on the 2001 publication from The University of Chicago Press, and features new texts from Musa Mayer and Debra Bricker Balken.

These trenchant works were created at an historic moment, amidst the tumultuous political climate of the early 1970s, as the United States suffered under the weight of civil unrest and social dissent following the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr and Senator Robert F Kennedy, the chaos of the 1968 presidential election, and the enduring violence and brutality of the Vietnam War. In his studio in Woodstock NY, Guston’s distress over the political situation was fuelled by conversations with his friend, the writer Philip Roth. The artist and the writer shared an intellectual disposition for the mundane ‘crapola’ of American popular culture, and in Nixon they discovered a subject they could each mimic and animate in art. During the summer of 1971, Roth had recently completed ‘Our Gang’, an outlandish political satire of the Nixon administration. Putting pen to paper, Guston similarly engaged in an artistic pursuit of the embattled president, turning toward the immediacy of drawing and revelling in the power of expressive line. The works in ‘Laughter in the Dark’ can be viewed within the distinguished tradition of political satire and social commentary by artists such as Hogarth, Daumier, Goya, and Picasso. Seeking a language to resolve a pictorial crisis that was at once personally and politically engaged, Guston’s adaptation of the comic-strip style of caricature emerged at a pivotal crux in his artistic career.

In May 1971, Philip Guston returned from an eight-month sojourn in Italy following the scathing critical response to his October 1970 Marlborough Gallery exhibition in New York. That first showing of his late figurative paintings had been assailed by critics and admirers of high Modernism as an act of heresy, a fully-fledged betrayal of abstract painting. Unravelled and deflated by attacks from critics like Hilton Kramer, who publicly denounced Guston as ‘A Mandarin Pretending to Be a Stumblebum’ (the headline of his biting New York Times review), the artist lamented the art world’s rigidity. ‘It was as though I had left the Church,’ he stated at the time. ‘I was excommunicated.’ Less than one year later, Guston would return to the US with his immersion in figuration and the aesthetic of transgression only reinforced by criticism. The works on view in the exhibition were created at this pivotal moment of Guston’s personal and artistic journey. The presentation opens with ‘Alone’ and ‘In Bed II’, two paintings from 1971 that culminate Guston’s outpouring of satirical Nixon images over the months of July and August that same year. Developed through the language of caricature, these works propose a new pictorial order that conveys both the pathos of a fraught inner terrain and the impossible turmoil of the exterior world. Each painting renders a solitary figure lying awake in bed, caught in an introspective state of contemplation and foreboding. These pictorial compositions suggest parallels between images of the young Nixon rendered in Guston’s Poor Richard series and the artist’s revealing self-portraits of later years. Noted by Charles McGrath in The New York Times: ‘The Nixon drawings share some of the vocabulary of the late Guston paintings, but have a larksome quality all their own. As the critic Peter Schjeldahl has pointed out, they’re hilarious but also compassionate in their way.’ The lexicon of images that first animated his Nixon drawings, here begins to substantiate the themes and iconography that give such potency to his late work.

The exhibition continues with the Poor Richard narrative from 1971, as well as works from The Phlebitis Series from 1975. Guston shared with Philip Roth great contempt for the newly elected Richard Nixon. This unwavering sentiment would intensify when The New York Times and The Washington Post published the so-called ‘Pentagon Papers’ in June 1971, revealing incalculable lies that had been fed to the American public about the country’s decades-long involvement in the Vietnam War. Nixon’s attempt to prevent the leaked documents from further disclosure – a decision overruled by the Supreme Court – exposed his character to satire and served to foreshadow the revelations to come with the Watergate break-in and the cover-up that eventually brought Nixon and his administration down. In a witty rebuttal to the president’s posturing, Guston caricatured Nixon’s self-mythologising identity, sly political manoeuvres, and disposable morals into a farcical cartoon canon. Aptly summarised by Juliet Helmke of Modern Painters: ‘the drawings hit you in the gut. They’re so simple and emotionally loaded… They’re worth the time in contemplation, despite, or even because of, the gloom that they might incite’.

Works from Guston’s sketchbooks offer a closer look at the artist’s working process and the development of his imagery. Here Guston’s parodies of the president’s humble upbringings and dirt-poor youth in the drawing of a locomotive engine billowing with black smoke. As the train departs from the ocean waves and exotic palm trees of the California coast, it reminds us of Nixon’s determined path toward early political success. To complete the dramatic scene-setting Guston borrows the phrase, ‘It seems like an impossible dream…’ from Nixon’s 1968 Presidential Nomination Acceptance Speech at the Republican National Convention, and memorialises it in clouds. In sketches where Nixon himself is depicted, Guston exaggerates anatomical attributes, notably Nixon’s famous five o’clock shadow, defiant gaze, swollen jowls and ever-growing nose. Nixon’s ‘schnoz’ is rendered as phallic morphology, becoming a visual cue for Guston’s condemnation of the president’s obscene deceits.

While Guston’s narrative follows Nixon from his youth to his eventual resignation of the presidency in 1974, the primary fuel for the Nixon drawings came from the events of July 1971. Encouraged by his trusted National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, Nixon announced plans to visit China and establish a new era of statesmanship and political relations. Dumbfounded by the hypocrisy of a man who had built his career upon a virulent anti-Communist stance, Guston conceived a slew of skits and sketches related to the voyage Nixon would take when visiting China in February the following year. The president is depicted nose-deep in a manuscript of mock-Chinese text, scheming and plotting in preparation. As the president frolics and plans for the hoopla of a fantastical ‘Asian Tour,’ never far from reach are his sidekicks Kissinger, Vice President Spiro Agnew, and Attorney General John Mitchell. As parallels to Nixon’s nose, Guston dreams up personifying attributes for each of these cronies: Agnew becomes a conehead, Mitchell dourly smokes his pipe, and Kissinger is represented only by a thick pair of rimmed spectacles.

Selecting 73 drawings from his scores of Nixon caricatures created in the summer of 1971, Guston edited the compositional chronology that makes up the Poor Richard series. Guston had originally intended to publish this sequence as a book, but a deep-seated ambivalence prevailed about these highly personal and politically profane works. In the three decades that followed, only a handful of the drawings – images produced two years before the Watergate scandal and three before Nixon’s political demise – were publically seen: In 2001, the Poor Richard series of 73 drawings were at last exhibited together and published in a volume of the same name by the University of Chicago Press.

Guston would return to the subject of Richard Nixon once more in his practice in 1975. After Nixon’s resignation under the threat of impeachment, Guston produced a final series of savage political drawings about the president. Poor Nixon is rendered as a ‘victim’ of the Watergate scandal he himself created and the revelations on the White House tapes he had ordered. The president’s phlebitis-afflicted leg – an ailment from which he suffered severely – is gargantuan, bandaged, and weighted. In the rarely exhibited painting ‘San Clemente’ (1975), Nixon, red-faced and inflamed, appears in agonising pain, dragging himself across the California beach with a self-pitying tear rolling down his cheek. Bunkered at his ‘Western White House’, the former leader of the free world has become a symbol of self-disgust and shame. Completed five years before the artist’s death, this remarkable painting stands as a monument to despair, and a meditation on aging and mortality.

Selected images

San Clemente

1975

Installation views

Related Content

About the Artist

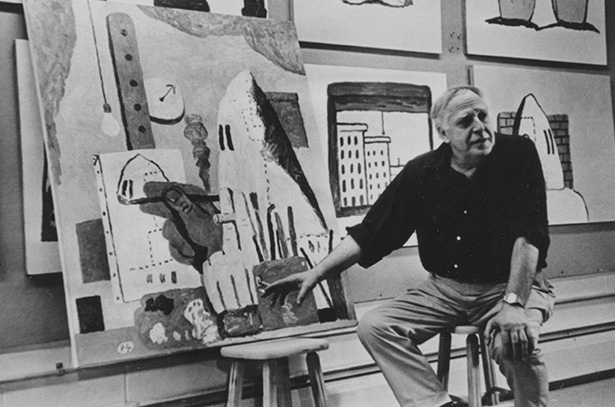

Philip Guston

Philip Guston (1913 – 1980) is one of the great luminaries of twentieth-century art. His commitment to producing work from genuine emotion and lived experience ensures its enduring impact. Guston’s legendary career spanned a half century, from 1930 to 1980. His paintings—particularly the liberated and instinctual forms of his late work—continue to exert a powerful influence on younger generations of contemporary painters. For an in-depth overview of his career, click here.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 12