Isa Genzken

I Love Michael Asher

16 October - 31 December 2016

Los Angeles

Beginning 16 October, Hauser Wirth & Schimmel will present ‘Isa Genzken. I Love Michael Asher,’ the first Los Angeles solo exhibition for the celebrated artist.

Isa Genzken was in her late 20s when she visited Michael Asher in California on a travel grant from Dusseldorf Academy, where she had begun teaching in 1977. At this time, Genzken was producing sleek lacquered wood sculptures known as ‘Ellipsoids’ and ‘Hyperbolos.’ This minimalist body of work, which lasted through the early 1980s, engaged with spatial and social aspects of line, mass, scale, color and movement through and around the works.

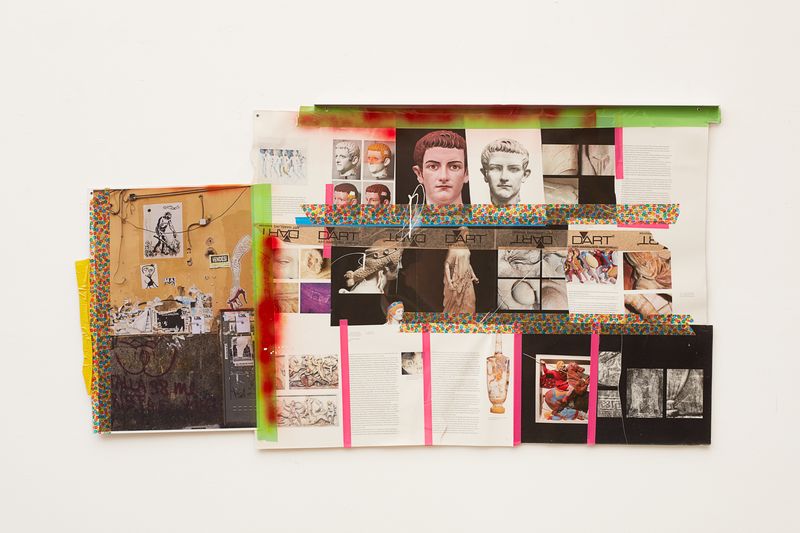

Since their meeting, Genzken’s diverse practice has encompassed sculpture, photography, drawing and painting. Her work borrows from the aesthetics of Minimalism, punk culture and assemblage art to confront the conditions of human experience in contemporary society and the uneasy social climate of capitalism.

In 1977, Michael Asher delivered small caravan trailer to the first Skulptur Projekte Münster. He had created sculpture out of experience, setting in motion his career-long project of ‘dislocation.’ In the years that followed, Asher’s interventions in galleries and museums included removing walls and doors, or keeping a museum open 24 hours a day. These deceptively simple architectural actions sought to expose the structural ‘givens’ of visual display and disrupt any sense of neutrality promised by galleries. Over a forty-year period, Genzken’s practice and Asher’s aligned in surprisingly fluid ways, despite the visual dissonance of their output. Both mined the formal tenets of sculpture, for example the base, or support structure – whether a plinth or a rolling cart for Genzken, for Asher a wall, window or even an entire city. Both artists present us with alternative (and often discomforting) environments and the critical tools to navigate contradictions around us.

In addition to her interior installation of all new works, this exhibition features in the Courtyard of the gallery, ‘Rose III,’ an 8-meter tall sculpture, modeled after an actual flower Genzken chose and sent to the foundry. The flower simultaneously defies and underscores the fragility and beauty commonly associated with the image of the rose.

Moreover, the towering sculpture brings to the fore ideas about the integration of architecture, nature, and mass culture. Genzken is focused less on the flower’s symbolism than the possibility of conveying a certain shine and shape, even resembling the mass-produced fake flowers found in dollar-stores. An interest in materiality, the bastardized legacy of modernism, and the relationship between the individual and the world is evoked in this exquisite sculpture, delivered with the artist’s unmistakable playful sense of humor.

Installation views

Related Content

About the Artist

Isa Genzken

Isa Genzken has long been considered one of Germany’s most important and influential contemporary artists. Born in Bad Oldesloe, Germany, Genzken studied at the renowned Kunstakademie Düsseldorf whose faculty at the time included Joseph Beuys, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Benjamin H.D. Buchloh and Gerhard Richter. Since the 1970s, Genzken’s diverse practice has encompassed sculpture, photography, found-object installation, film, drawing and painting. Her work borrows from the aesthetics of Minimalism, punk culture and assemblage art to confront the conditions of human experience in contemporary society and the uneasy social climate of capitalism.Genzken is best known for her sculptures, gaining attention for her minimalist oriented Hyperbolos and Ellipsoids in the late 70s, and architecturally-inflected works such as her recent epoxy resin windows and skyscraper Columns from the 90s. Genzken’s practice is incredibly wide-ranging, but her work remains dedicated to challenging the viewer’s self-awareness by means of physically altering their perceptions, bringing bodies together in spaces and integrating elements of a mixed media into sculpture.

Genzken’s totemic columns, pedestal works and collages combine disparate aspects from her many sources in seemingly nonsensical, yet harmonious sculptural compilations. These sculptures take the form of precariously stacked assemblages of potted plant designer furniture, empty shipping crates and photographs, among other things, arranged with the traditions of modernist sculpture in mind. With this cacophonous array of objects, Genzken undermines the classical notions of sculpture, re-creating the architectural dimensions of her beloved skyscrapers and the riotous colors of the city streets. Devoid of the weightiness and overpowering scale seen in the sculptures of her Minimalist predecessors, her work abandons notions of order and power, allowing the viewer to relate to the works’ inherently human qualities of fragility and vulnerability.

Inspired by the stark severity of modernist architecture and the chaotic energy of the city, Genzken’s work is continuously looking around itself, translating into three-dimensional form the way that art, architecture, design and media affects the experience of urban life, and the divides between public and private. There is an intuitive and consistent manner to Genzken’s work, not only in dramatising aspects of space and scale for the audience, but in creating new dialogues and contact with surfaces of material. The socio-political content is evident and central to her oeuvre.

In 2017, Genzken was awarded the prestigious Goslarer Kaiserring (or Emperor’s Ring) by the city of Goslar, Germany.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 12