Louise Bourgeois & Pablo Picasso

Anatomies of Desire

9 June - 14 September 2019

Zürich

Hauser & Wirth Zürich is proud to present ‘Louise Bourgeois & Pablo Picasso: Anatomies of Desire’ which opens during Zurich Art Weekend on 8 June 2019. The exhibition is the first time that Picasso is exhibited in a dual dialogue with a female sculptor and brings together over 90 works including paintings, sculptures and works on paper from important public institutions and private collections such as the Fondation Beyeler (Riehen/Basel), Nasher Sculpture Center (Dallas), and Kunstmuseum Den Haag (The Hague). Curated by highly renowned specialist Marie-Laure Bernadac, former curator at the Louvre, Musée Picasso (Paris), and Centre Pompidou, the exhibition is organised in close collaboration with the Louise Bourgeois Studio.

The aim of the exhibition is to foster a discourse on the work of Bourgeois and Picasso by exploring the differences and affinities in the artists’ formal, thematic and iconographic language. The presentation will display intentional pairings of works, ‘by placing these artists together for comparative analysis, this exhibition sheds new light on their oeuvres and rids us of the clichés of the virile painter armed with a phallic brush and the sculptress armed with a knife,’ explains curator Marie-Laure Bernadac. The original inspiration for the pairing came from an exhibition organised by the Beyeler Foundation in 2011, curated by Ulf Küster, which presented works by Bourgeois in dialogue with works by modern masters from the Beyeler collection confirming the artist’s position as one of the key bridges between modern and contemporary art.

This exhibition takes ‘the couple’ as its guiding theme, a de facto marriage of these two artists yet also an allusion to subjects crucial to them: man and woman, sexuality, pregnancy, and maternity. While Bourgeois and Picasso embody different conceptions of the artist-type, and do not have a formal affinity or similar sensibility, they share an interest in the topic of sexuality. What Bourgeois said of herself could equally apply to Picasso: ‘…my centre is my sexuality. Everything lies there. It is the fixed point.’

The embrace is a recurring theme for Picasso who turned two beings into one, expressing the carnal fusion that occurs in the act of kissing in the painting ‘Le Baiser’ (1969). Depicted in cinematic close-up, the two profiles of man and woman merge in a single line as they clash and curl in figures of eight. The theme of the couple – or rather of coupling – appears repeatedly in Bourgeois’s oeuvre, for example, in drawings from the 1940s showing male and female profiles face-to-face. Bourgeois’s Landscape series of 1967, with its poured formations suggestive of human contours, developed from the amorphous plaster and latex pieces of the early sixties. Across the surface of ‘End of Softness’ (1967) emerge undulating protuberances and coagulations that stretch and sometimes penetrate the surface. The work merges male and female, hardness and softness in an uncanny and ambivalent fusion, as if implying a metamorphosis frozen in time.

Louise Bourgeois and Pablo Picasso never met. They belonged to different generations, Picasso being born in the late nineteenth century (1881–1973), and Bourgeois in the early twentieth century (1911–2010). While Bourgeois amply knew and admired Picasso’s work – she once claimed a Picasso exhibition in New York ‘revealed such genius and such a collection of treasures that I did not pick up a paintbrush for a month’ – it would seem that Picasso never saw her work, which was almost totally unknown in France in the 1960s and 1970s.

However, there are striking similarities between their biographies and artistic approaches. Both Bourgeois and Picasso were precocious children, raised in the artistic atmosphere of a family workshop, who developed an obsession with collecting and archiving personal items. They believed in the power of the word and produced an abundant poetic output: Picasso’s was voluminous and calligraphic, Bourgeois’s was obsessively diaristic, yet also visual and literary. Both artists also felt that art is profoundly autobiographical and saw their output as a form of physical incarnation and also took recourse to archaic, primitive sources of creativity. These subjects were handled in varied ways throughout their careers.

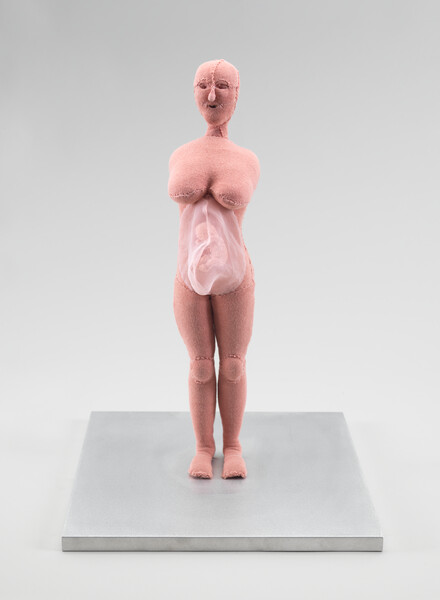

The artists deciphered and developed their ideas around fertility, represented by mother deities, although here the marked divergence between their approaches can be seen in Bourgeois’s nuanced and ambivalent portrayals of the mother figure. Pregnancy appeared in Bourgeois’s oeuvre as early as 1947 with ‘Pregnant Woman’, a hieratic figure in wood and plaster, like some primitive idol. Later, in the early 2000s, there were the figurines in pink fabric, here the infant was sometimes positioned on the outside of the mother’s belly, enclosed in a transparent, tulle, womb-like sac to convey its fragility. Few artists dealt with the scene of childbirth in such a recurrent, explicit fashion – the infant exiting the womb or clinging to its umbilical cord. These late depictions are a metaphor of rebirth, of creative power, and the cyclical return, in old age, to the condition of a newborn. Picasso depicted pregnancy several times, such as in the sculpture ‘Femme enceinte (Pregnant Woman)’ of 1950 to 1959, whose belly and breasts in the original plaster were made from terracotta vases. This sculpture was created when Picasso’s partner, Françoise Gilot, was pregnant first with Claude and then with Paloma, and he explores the metamorphosis of a woman’s body through pregnancy.

A new publication by Hauser & Wirth Publishers, entitled ‘Louise Bourgeois & Pablo Picasso: Anatomies of Desire’, coincides with the exhibition and further develops the thought-provoking discourse on these artists’ work. The publication builds upon the complex conversation about gender this exhibition sparks, with newly commissioned texts by exhibition curator Marie-Laure Bernadac (former curator at the Louvre, Musée Picasso Picasso (Paris) and Centre Pompidou), Émilie Bouvard (art historian and curator), Jerry Gorovoy (President of Louise Bourgeois’s Foundation, The Easton Foundation), Ulf Küster (curator at the Fondation Beyeler), Gérard Wajcman (psychoanalyst and writer), and Diana Widmaier Picasso (art historian).

The exhibition is part of a programme of Hauser & Wirth activities coinciding with Zurich Art Weekend. A new global headquarters for Hauser & Wirth Publishers on Rämistrasse, in the heart of Zurich’s cultural district, opens on Saturday 8th June with a book launch for ‘Louise Bourgeois & Pablo Picasso. Anatomies of Desire’. Also opening is an exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Zürich entitled ‘max bill bauhaus constellations’ curated by Dr Angela Thomas Schmid, President of the Max Bill Georges Vantongerloo Stiftung.

Installation views

Related Content

About the Artist

Louise Bourgeois

Born in France in 1911, and working in America from 1938 until her death in 2010, Louise Bourgeois is recognized as one of the most important and influential artists of the 20th Century. For over seven decades, Bourgeois’s creative process was fueled by an introspective reality, often rooted in cathartic re-visitations of early childhood trauma and frank examinations of female sexuality. Articulated by recurrent motifs (including body parts, houses and spiders), personal symbolism and psychological release, the conceptual and stylistic complexity of Bourgeois’s oeuvre—employing a variety of genres, media and materials—plays upon the powers of association, memory, fantasy, and fear.

Bourgeois’s work is inextricably entwined with her life and experiences: fathoming the depths of emotion and psychology across two- and three-dimensional planes of expression. ‘Art,’ as she once remarked in an interview, ‘is the experience, the re-experience of a trauma.’ Arising from distinct and highly individualized processes of conceptualization, Bourgeois's multiplicity of forms and materials enact a perpetual play: at once embedding and conjuring emotions, only to dispel and disperse their psychological grasp. Employing motifs, dramatic colors, dense skeins of thread, and vast variety of media, Bourgeois's distinctive symbolic code enmeshes the complexities of the human experience and individual introspection.

Rather than pursuing formalist concerns for their own sake, Bourgeois endeavored to find the most appropriate means of expressing her ideas and emotions, combining a wide range of materials—variously, fabric, plaster, latex, marble and bronze—with an endless repertoire of found objects. Although her oeuvre traverses the realms of painting, drawing, printmaking, and performance, Bourgeois remains best known for her work in sculpture.

Bourgeois’s early works include her distinct 'Personages' from the late 1940s and early 1950s; a series of free-standing sculptures which reference the human figure and various urban structures, including skyscrapers. The ‘Personages’ served as physical surrogates for the friends and family Bourgeois had left behind in France, while also highlighting an interest in architecture dating back to her childhood. Her installation of these sculptures as clustered ‘environments’ in 1949 and 1950 foreshadowed the immersive encounters of installation art twenty years before the genre’s rise to prominence.

Bourgeois’s work was included in the seminal exhibition ‘Eccentric Abstraction,’ curated by Lucy Lippard for New York's Fischbach Gallery in 1966. Major breakthroughs on the international scene followed with The Museum of Modern Art in New York's 1982 retrospective of her work; Bourgeois's participation in Documenta IX in 1992; and her representation of the United States at the 45th Venice Biennale in 1993.

In 2001, Bourgeois was the first artist commissioned to fill the Tate Modern’s cavernous Turbine Hall. The Tate Modern’s 2007 retrospective of her works, which subsequently traveled to the Centre Pompidou in Paris; The Guggenheim Museum in New York; The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; and The Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C., cemented her legacy as a foremost grande dame of late Modernism.

Header image: Louise Bourgeois, ARCHED FIGURE, 1993 © The Easton Foundation/VAGA, NY, Photo: Christopher Burke

Current Exhibitions

1 / 12