max bill

bauhaus constellations

9 June - 14 September 2019

Zürich

To coincide with the Bauhaus centenary, Hauser & Wirth is proud to present a major exhibition entitled ‘max bill bauhaus constellations’. Opening in Zurich during Zurich Art Weekend 2019, the exhibition, curated by Dr Angela Thomas Schmid, President of the Max Bill Georges Vantongerloo Stiftung, explores the dynamic dialogues between the group of artists Max Bill met at the influential Dessau school. The exhibition aims to investigate Bill’s creative development of his interactions at the Bauhaus, which ultimately led to the establishment of his own internationally acclaimed design school, the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, Germany, and solidified his place as a seminal figure in the Concrete Art movement. The artists featured alongside Bill include Josef Albers, Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, Kurt Schwitters, Oskar Schlemmer, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Georges Vantongerloo.

The inaugural exhibition of Max Bill’s work at Hauser & Wirth Zürich displays a selection of important paintings and sculptures that Bill created after his time at the Bauhaus, from the 1930s to the 1980s, alongside a range of smaller works by connected Bauhaus artists, Bill’s teachers and some of his fellow students, as well as archive materials Bill assembled during his lifetime. These pieces contextualise the works by Bill, forming a visual constellation around his oeuvre which can be traced as references by the viewer. The division of works sets out to demonstrate the formative and lasting influence that the Bauhaus had on Bill’s artistically and socially engaged practice – which spanned architecture, sculpture, painting, typography and design – giving insight into the relevance of his work.

Max Bill was born in Winterthur, Switzerland in 1908. Originally studying as a silversmith’s apprentice, he became fascinated with modern architecture upon encountering Le Corbusier’s L’Esprit Nouveau and Konstantin Melnikov’s pavilion for the USSR at the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs in 1925. Shortly after this encounter, Bill discovered Weimar-era Bauhaus materials in a bookshop in Zurich, edited by the school’s founder, Walter Gropius and professor László Moholy-Nagy. After learning that a ‘new’ Bauhaus was to open in Dessau in 1926, the artist applied and was accepted in April 1927 at 18 years old.

Established in 1926, the Dessau school followed the forced closure of the Weimar Bauhaus institution in 1925, after the city’s nationalist government withdrew its financial support in a time of shifting political agendas. As a student entering the ‘second phase’ of the Bauhaus, Bill studied under the guidance of Bauhaus Masters Josef Albers, László Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Oskar Schlemmer, officially until 1928. The tenets of the Bauhaus, including a modern and scientific approach to colour and Constructivist form, with a utopian vision of unity and community across art and design, would inform Bill’s interdisciplinary work for the rest of his life.

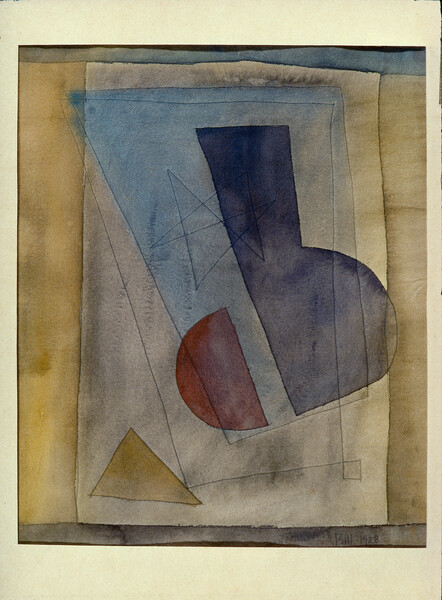

Important paintings in the exhibition by Bill, such as ‘Horizontal-vertikal-diagonal-Rhythmus (Horizontal-vertical-diagonal-rhythm)’ (1942) and later works such as ‘Reflexe aus dunkel und hell (Reflections from dark and light)’ (1975) reflect many principles of colour and form taught by Albers in the Bauhaus’s ‘Vorkurs’ (preliminary course). These subjects were approached theoretically, examining the elementary notions of visual experience, often through the coalescence of colour and shape. In these paintings, the geometric elements of Bill’s work are submerged with colour, becoming unified entities whilst echoing the aesthetic affinities of his contemporary Piet Mondrian. Although previously reminiscent of Klee and Mondrian, Bill’s artistic style focused on the rational, rather than the spiritual, which would come to inform his involvement within the Concrete Art movement – a term first coined by Theo van Doesburg that Bill would eventually popularise. The creation of visual harmony through the symmetry of colour and form is explored by Bill in his work ‘Rot und grün aus blau und gelb (Red and green from blue and yellow)’ (1970).

These works recall the essential shapes of Bauhaus design – the triangle, circle, and square – which predominately feature throughout Bill’s practice, as well the oeuvres of many of his Masters, such as Moholy-Nagy. Works by Bill such as ‘Glasbild (Glass Picture)’ (1930-1931) and ‘Well-Relief (Corrugated Relief)’ (1931-1932) are particularly significant through the artist’s use of minimal, basic forms, combined with low-cost materials (such as iron and glass), anticipating stylistic traits seen in both American Minimalism and Arte Povera.

The exhibition also presents a number of important sculptures from the Max Bill estate. Works such as ‘Konstruktion aus 30 gleichen Elementen (Construction from 30 identical elements)’ (1938-39) and ‘Unendliche Fläche in Form einer Säule (Continuous space in form of a column)’ (1953) conjure aesthetic elements seen in Melnikov’s pavilion of the Soviet Union. Curator Angela Thomas Schmid notes that Bill saw himself as an ‘engineer of space’ and believed that sculptors could learn something from civil engineers, mirroring the Bauhaus concept of merging life and art. Following the maxim ‘form follows function’, the Bauhaus allowed its students to consider the moral and ethical implications of bringing a product or artwork into the world – an idea which was particularly promoted in Albers’ ‘Vorkurs’, whereby he encouraged his students to salvage low cost materials from the rubbish-dumps of Dessau. Upholding the influential teachings and culture of the Bauhaus, Bill never disregarded the social implications of the work he made. He insisted later during his time as principal at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm: ‘if you design something for the public, you must assume social responsibility’.

After leaving the Bauhaus, Bill moved to Zurich and began experimenting with and expanding the possibilities of Concretism to further define his fascination with scientific and geometric foundations utilised in the creation of objects – whether sculptures, paintings, or functional objects – that he considered the physical manifestations of rationalism. In the 1930s, he travelled to Paris and began to exhibit with the Abstraction-Création group, establishing relationships with several older artists, such as Piet Mondrian and Georges Vantongerloo, who was to become a lifelong friend. Bill was later accepted as an artist in his own right by his Bauhaus professors and was later invited by Moholy-Nagy to teach at his ‘new Bauhaus’ school in Chicago, however Bill declined his offer. A few years later in 1953, Bill built, established and directed the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm. Amongst others, he invited Josef Albers as a guest professor who came to teach at the school twice.

Bill’s influence and reach were felt internationally, and the social responsibilities he associated with producing art and design still resonate with artists today. By examining the relationships between Bill and his Bauhaus contemporaries, ‘max bill bauhaus constellations’ celebrates the profound influence this artist and school have had on 20th and 21st century art and society.

The exhibition is part of a programme of Hauser & Wirth activities coinciding with Zurich Art Weekend. A new global headquarters for Hauser & Wirth Publishers on Rämistrasse 5, in the heart of Zurich’s cultural district, opens on Saturday 9 June. The new headquarters will occupy the former home of the Oprecht & Helbling bookshop, opened in 1925, and Emil and Emmie Oprecht’s legendary Europa Verlag publishing house, founded in 1933, who Max Bill designed several book covers for. Bill also designed the anti-fascist magazine ‘information’ from 1932 until 1934, published by the Oprechts, as well as the Europa Verlag’s 1933 publishing catalogue. Hauser & Wirth Publishers launches with a new publication ‘Louise Bourgeois & Pablo Picasso. Anatomies of Desire’, coinciding with an important exhibition pairing Bourgeois and Picasso which opens at Hauser & Wirth Zürich on the 8 June.

Selected images

Installation views

Related Content

About the Artist

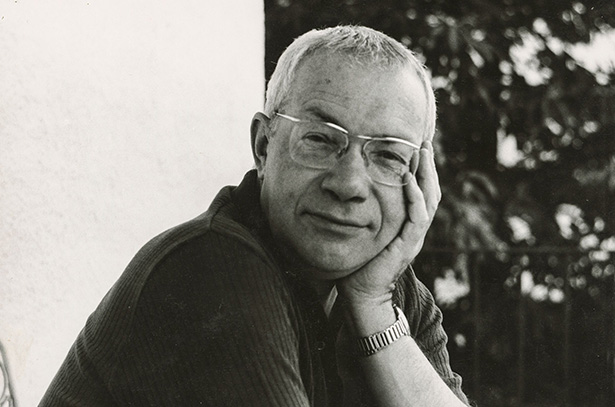

Max Bill

Max Bill was a great Swiss polymath: an artist, architect, industrial designer, graphic designer, and teacher. He attended the Bauhaus where he was taught by Josef Albers, László Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Oskar Schlemmer. Bill remained closely associated with the Bauhaus school and was a key figure in developing and propagating its principles, especially through his professorship at the Kunstgewerbeschule Zürich and as a founder of the Ulm School of Design. Through his pursuit of a new visual language that could be understood by the senses alone, Bill defined the conventions of Swiss design for decades to come. His influence spread even as far as South America, where he was a catalyst for the Concrete Art movement.

Bill was born in Winterthur, Switzerland in 1908. Originally studying as a silversmith’s apprentice, he became fascinated with modern architecture upon encountering Le Corbusier’s L’Esprit Nouveau at the Paris Exposition des Arts Décoratifs in 1925. After finding Bauhaus materials in a bookshop in Zurich, Bill applied and was accepted to the Bauhaus school in Dessau, studying under the guidance of such teachers as Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee from 1927 to 1928. The tenets of the Bauhaus, including a modern, scientific approach to colour and Constructivist form, would inform his interdisciplinary work in art, architecture, and design for the rest of Bill’s life.

After leaving the Bauhaus, Bill moved to Zurich and began experimenting with and expanding the margins of Constructivism. He would eventually popularize the term Concrete Art (first coined by Theo van Doesburg) to further define his fascination with mathematical and geometric foundations utilized in the creation of objects—whether sculptures, paintings, or functional objects—that he considered the physical manifestations of rationalism. Bill never disregarded the social implications of the work he made; against the backdrop of Nazi Germany and World War II, Bill insisted, ‘if you design something for the public, you must assume social responsibility.’ Bill was a key member in a number of artist groups, including the Allianz group in Zurich and Abstraction-Création in Paris.

Bill executed many public sculptures in Europe and his work was exhibited extensively in galleries and museums during his lifetime, including a retrospective at the Kunsthaus Zürich in 1968 – 69. His first exhibition in the United States was presented at the Staempfli Gallery in New York City in 1963; U.S. solo exhibitions were presented at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1974. In 1993, he received the Praemium Imperiale for sculpture.

Bill is credited with having been helped to inspire Brazil’s the Concrete Art movement with his 1951 retrospective at the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art.

The Max Bill Georges Vantongerloo Stiftung was established by Bill’s widow, the independent curator and scholar Dr. Angela Thomas Schmid, to represent the part of these two artists’ estates entrusted to her care. Despite maintaining entirely distinct artistic practices, artists Max Bill and Georges Vantongerloo were bound together in their desire to forge new developments in the field of twentieth-century abstraction, and by their lifelong friendship. Their close relationship and an extended personal written correspondence—which unfolded over the course of more than three decades—united their independent artistic and intellectual endeavours, and helped each to push the boundaries of his work to the fullest. The progress of this extraordinary creative exchange mirrors the artistic and philosophical breakthroughs that defined the last century.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 12