Cathy Josefowitz

Forever Young

11 May – 22 July 2023

New York, 69th Street

Hauser & Wirth New York presents ‘Forever Young,’ our first exhibition devoted to the art of Cathy Josefowitz (1956 – 2014). This focused presentation, occupying two floors of the gallery’s 69th Street location, celebrates Josefowitz’s life, vision and achievements through a meticulous selection of works, including many on view for the first time.

About the exhibition

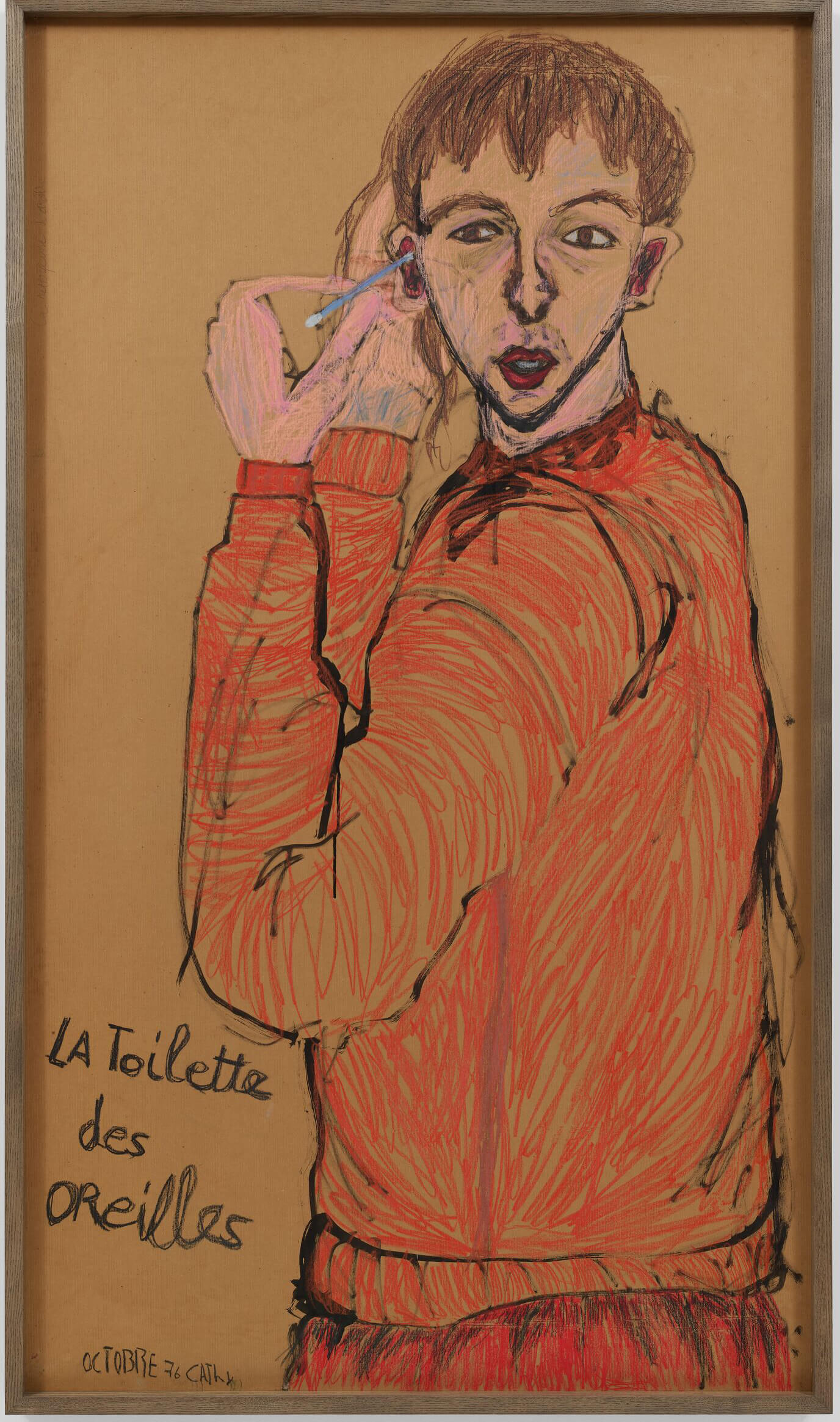

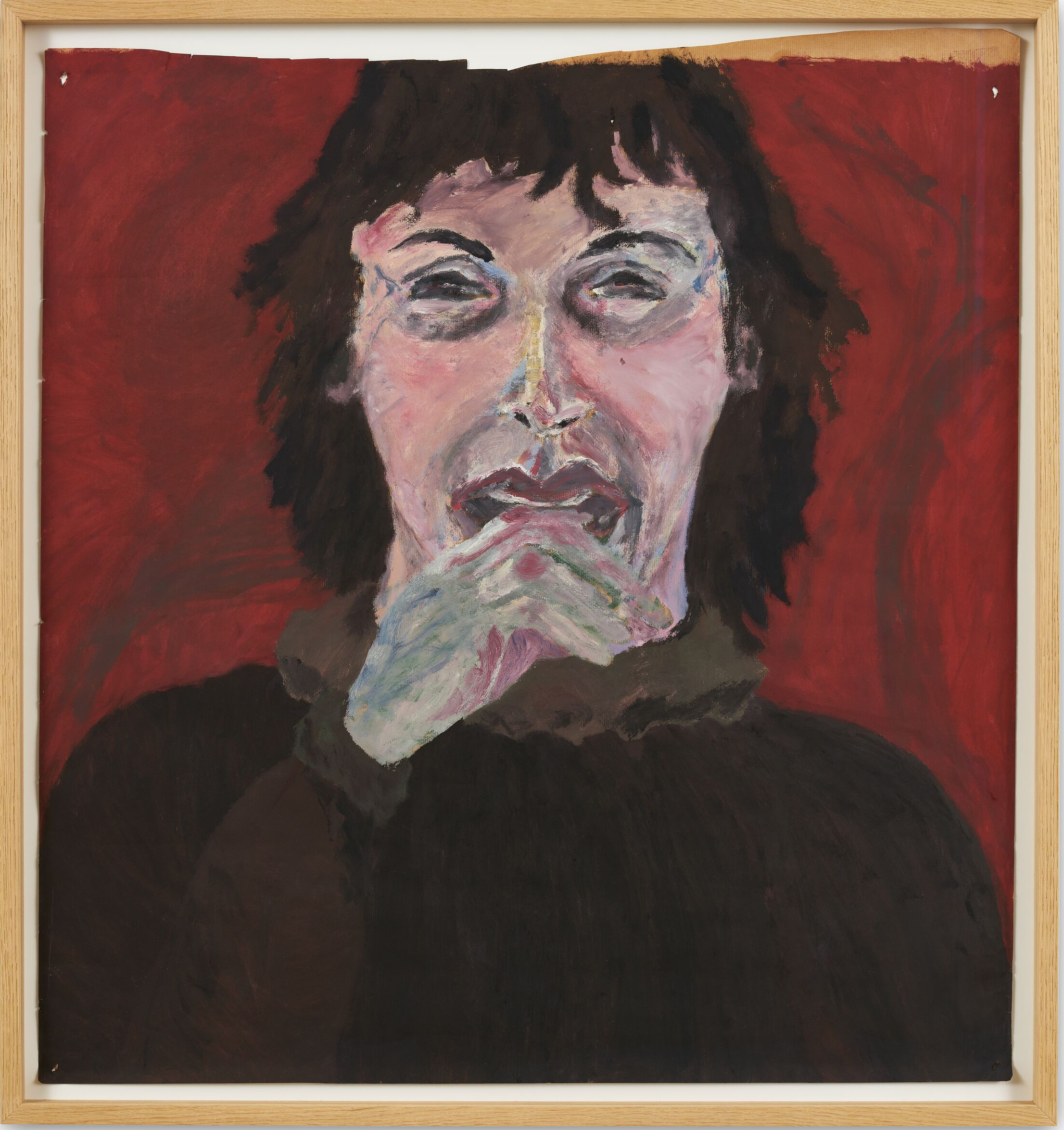

Featuring a series of paintings, works on paper—including pastel, felt- tip pen, ink, gouache and watercolor—and rare film footage from two choreographies, the exhibition spotlights the earliest works in Josefowitz’s practice and explores traces of these pivotal breakthroughs that persisted throughout her career.

Cathy Josefowitz: “Sometimes an ideal world…”

A short film about the life and art of Cathy Josefowitz, narrated by Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel and directed by Freddie Leyden.

‘Painting is the only thing I know how to do, it's like breathing, it's natural. I paint because I need to, because if I don't paint, I go crazy I need to express, it's my way of existing.’

—Cathy Josefowitz

The exhibition opens with a group of paintings produced during the early 1970s when Josefowitz was living in Paris, where she moved to study at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Influenced by several major 20th-century artistic movements, from fauvism and expressionism to Der Blaue Reiter, these early paintings reveal the artist’s incipient desire to show intimacy expressed through the quotidian as well as the inspiration she drew from cherished memories of her family and childhood.

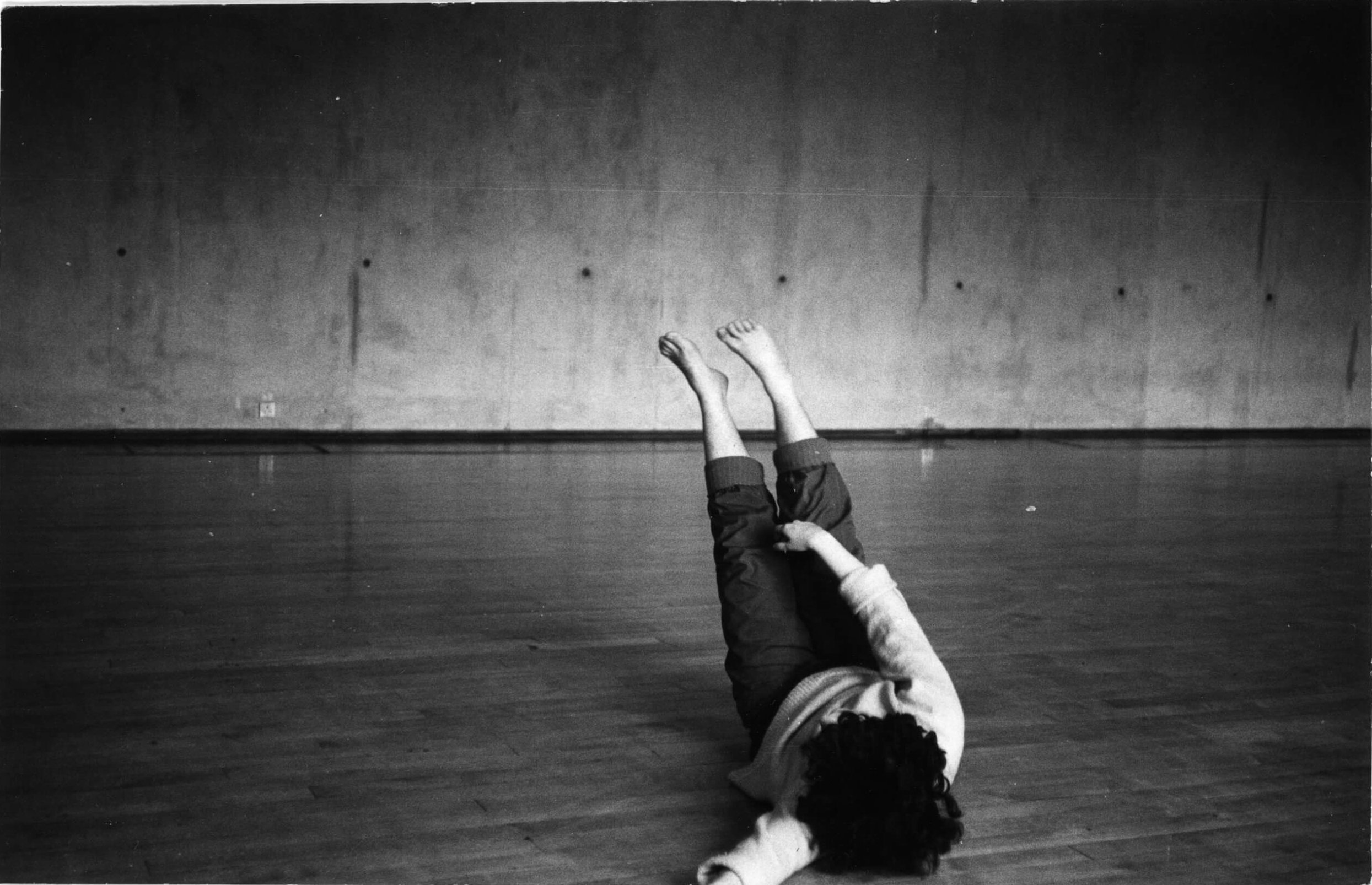

Anchoring the gallery’s first floor is film footage of Josefowitz’s first choreography, ‘Woodstock’ (1983). Having attended the renowned Dartington College of Arts in Devon, England from 1979 to 1983, where she studied with such masters of contemporary dance as Steve Paxton and Mary Fulkerson, Josefowitz sought to dismantle the conventional hierarchy that separated performance and painting at that time and reconcile these two mediums in her practice. On stage, the symbols and themes that punctuated Josefowitz’s pictorial work became the subject of her choreographies.

‘l was crippled by the image of myself. I choose to express myself through the art of painting and drawing. As I grew older the paintings became bigger till they reached human size, the topics were always people. Colourful people in energetic activities.’

—Cathy Josefowitz

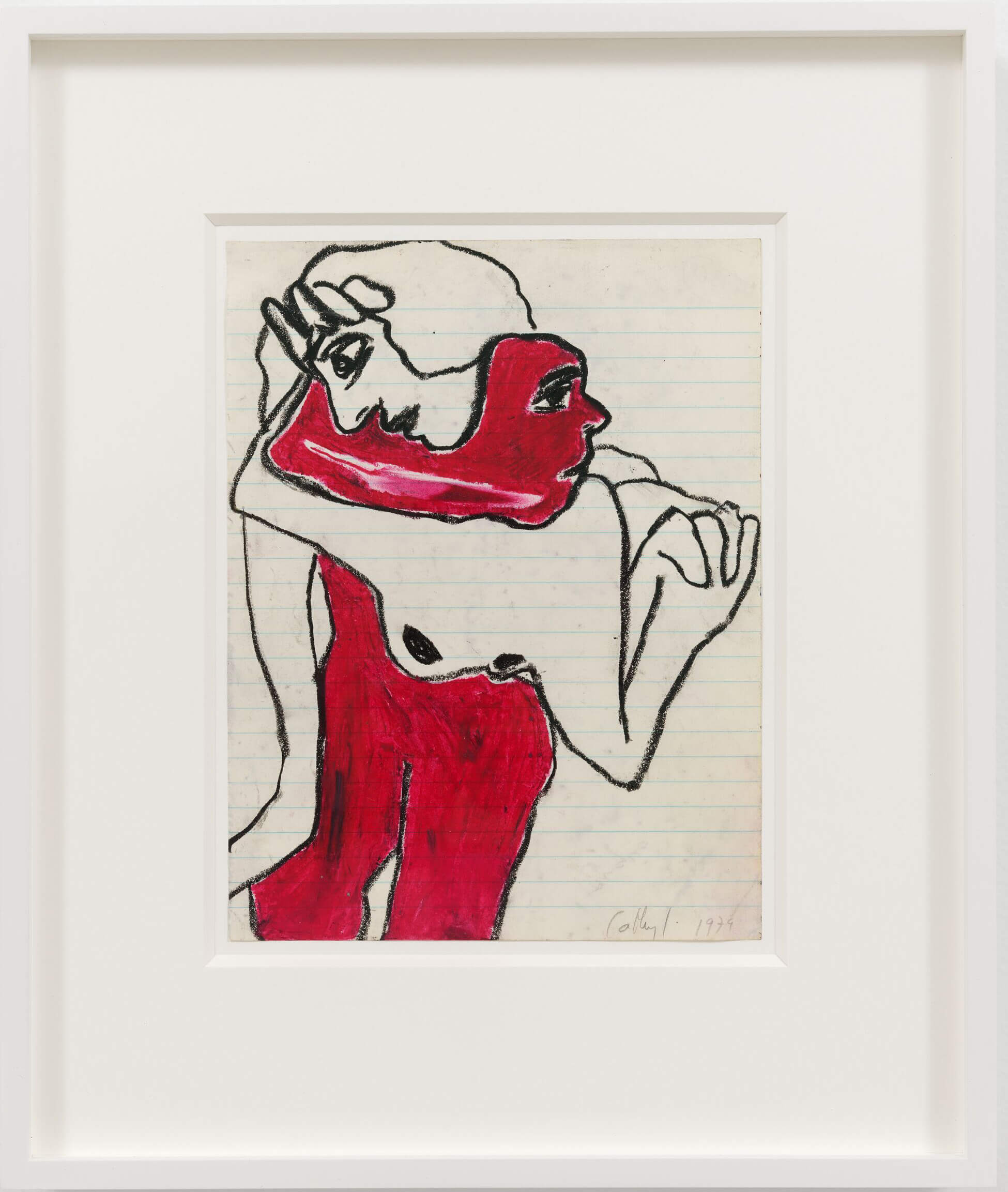

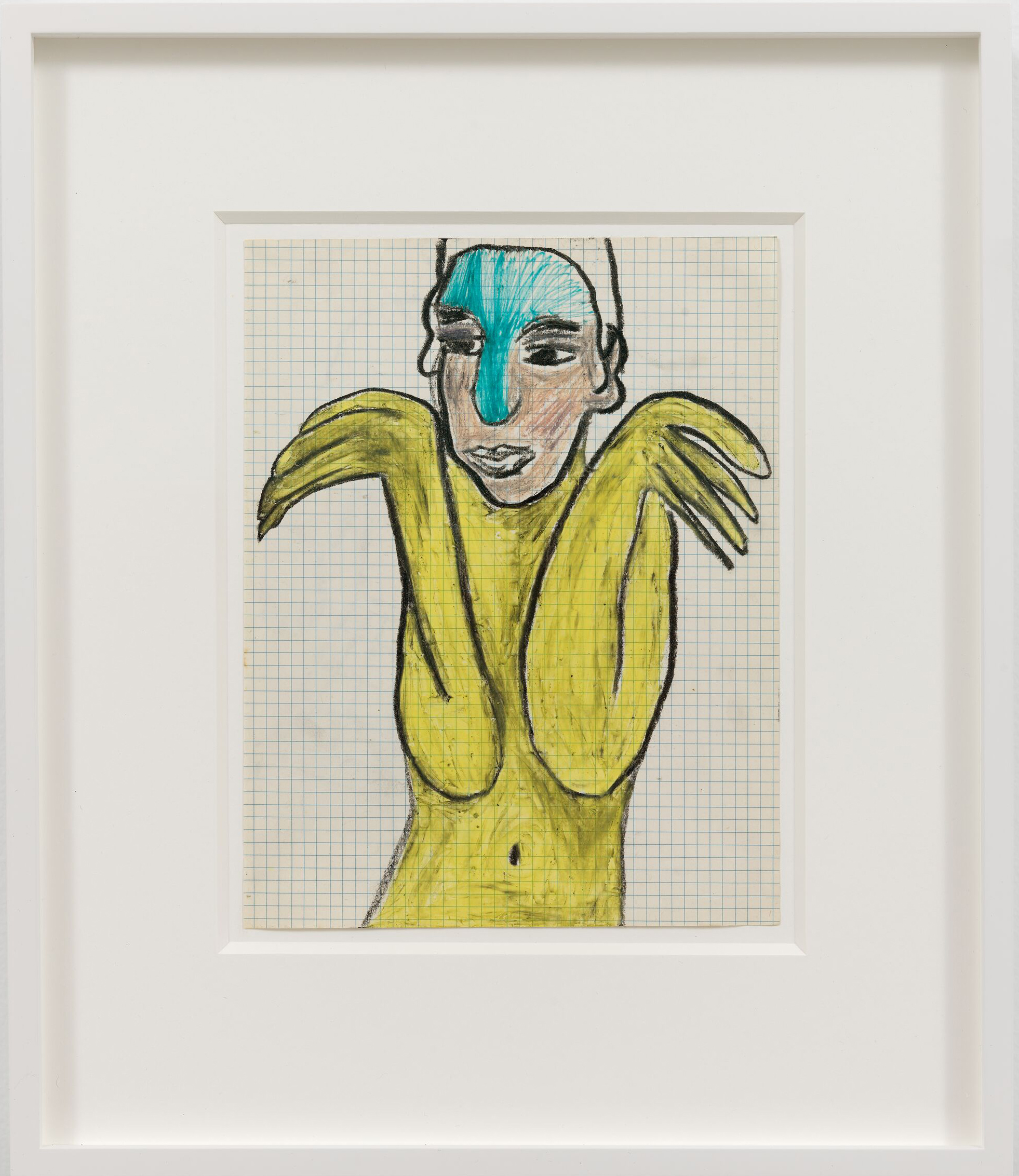

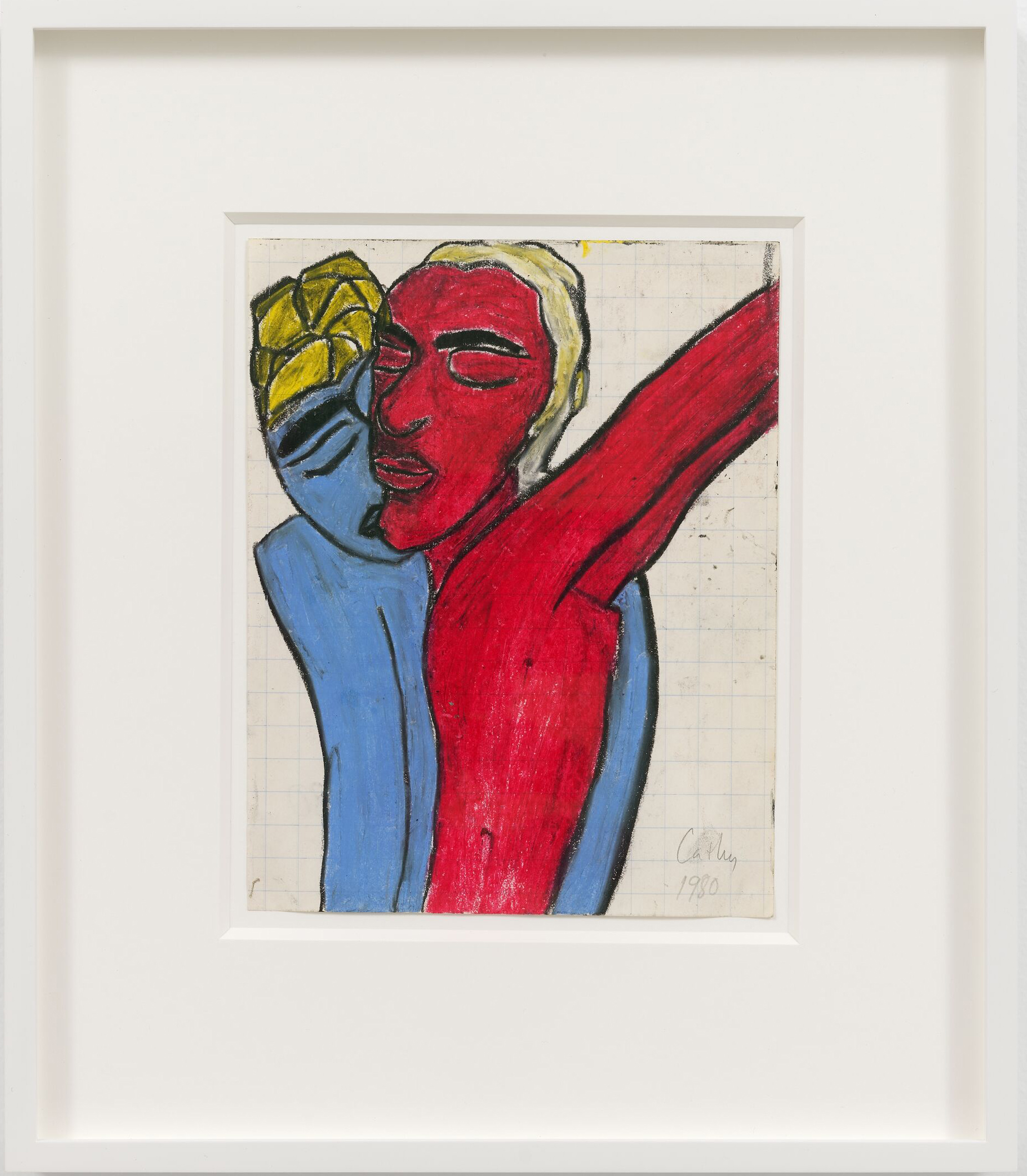

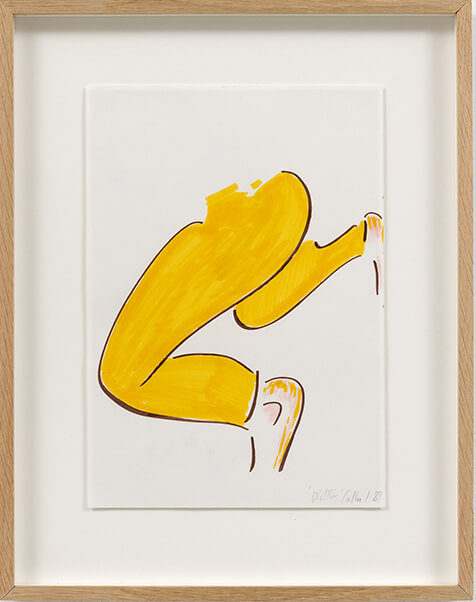

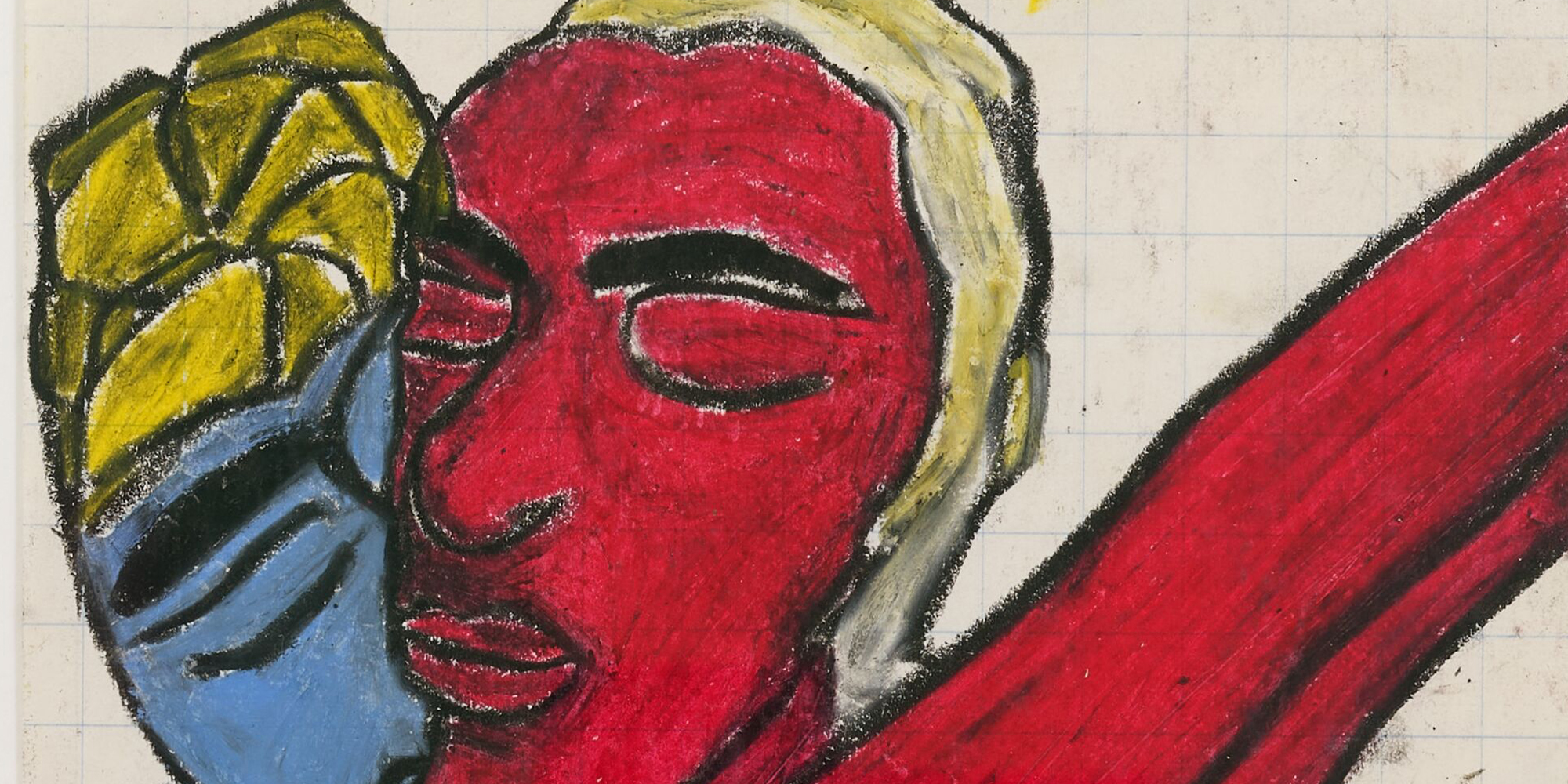

As the exhibition moves to the second floor, viewers are exposed to the drawings that allowed Josefowitz, in even more immediate terms than painting, to realize the physical possibilities of the body. A selection of works on paper demonstrate how the artist used pastels to represent sensation through raw, unvarnished and increasingly distorted figures, capturing the body in both its anatomical and metaphysical dimensions. Executed on the pages of small notebooks that she always carried, these drawings exhibit the characteristic warping and exaggeration of her subjects’ anatomy, permitting her to convey the tenderness of an embrace or a figure’s exaggerated gesture and gaze more fully.

‘When I create my choreography, I work in the same way as in my paintings, I do a lot of drawings from each choreography, I draw nearly every single scene.’

—Cathy Josefowitz

Josefowitz also began her painting sessions with a dance as her practice moved further into abstraction and the exploration of space on both the stage and the canvas, which in turn resulted in the gradual disappearance of the body from her oeuvre. This evolution is evident in such oil paintings as ‘Triptyque bleu blanc rouge’ (1994) that depict eerily anthropomorphic chairs, a direct reference to ‘For Ever Young,’ in which she captured the body in motion, fading—or falling away—into the canvas, in a single abstracted image.

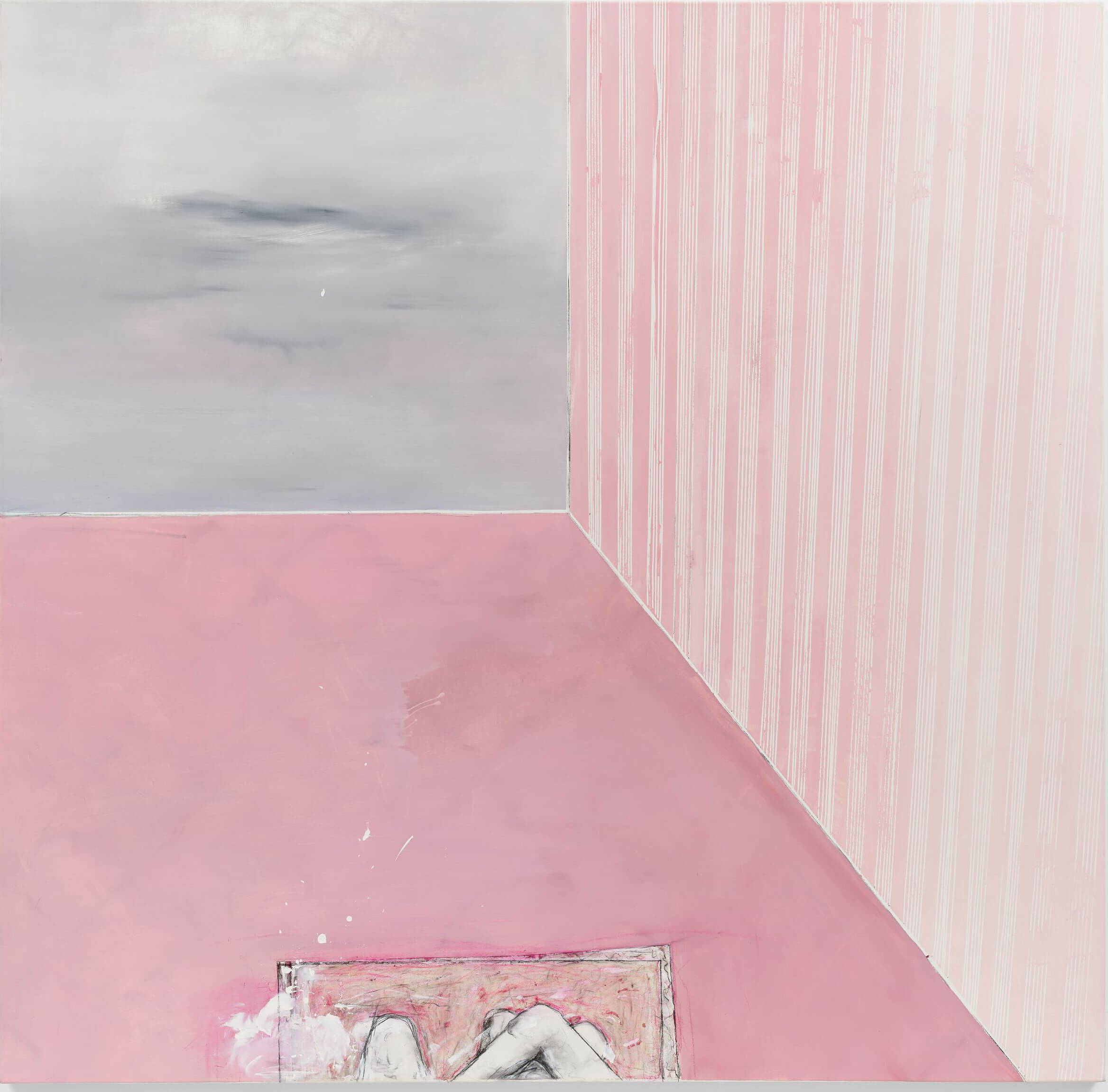

Her Kamasutra paintings from 2009 and 2010—inspired by the Indian mystic Osho, whose teachings promoted the celebration of life—show couples having sex while also minimizing the human body to such a degree that it is hardly discernible against the limitless, monochromatic space surrounding the figures. With this focus on shading, geometry and ambiguous settings, Josefowitz would in the last years of her life use these elements to evoke the same emotional resonance of the spirit that she had, until this point, used the body itself to summon. In the last paintings that the artist produced, the figure disappeared from her oeuvre entirely, giving way to a total abstraction that liberated the artist in her quest to dispense with limits and restrictions.

About the Artist

Cathy Josefowitz

Prolific, prescient and powerfully original yet under-recognized in her lifetime, Josefowitz (1956 – 2014) produced a diverse body of work that ingeniously transcends hierarchies of medium and genre. Over the course of four decades, this New York-born, Swiss-raised artist created an oeuvre of remarkable ambition, spanning drawing and painting, theater and dance, as she developed a deeply personal visual syntax in her quest to represent the body as an expressive vehicle of individual experience. Josefowitz’s practice reconciled the visual arts and performance, leaving an exceptional legacy as substantial in scale as it is intimate and potent in its impact.

Born in New York in 1956, Cathy Josefowitz spent her childhood and adolescence in Geneva, Switzerland, from the age of two and a half. Manifesting the inherent gifts of a musical conductor father and artist mother, she taught herself to draw at the age of four in a moment she would later describe as ‘finding her voice.’

Josefowitz’s lifelong fascination with bodily experience was sparked in part by her study of stage design at the Théâtre National de Strasbourg in 1972. Driven by a relentless need for self-expression, she continued her exploration of the corporeal in works on paper that articulated the different configurations a human body can take as a form of both resilience and liberation. She frequently drew in notebooks, depicting her dreams and inner world, while also developing her practice on canvas. Her art quickly revealed a unique awareness of and sensitivity to the physical forms of the self and of those marginalized and made vulnerable by society.

In 1973, while studying at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Josefowitz made large figurative paintings on kraft paper and cardboard that channeled the influence of major artistic movements of the 20th Century, including fauvism, expressionism and Der Blaue Reiter. Likewise influenced by such female artists as Louise Bourgeois, Josefowitz soon came to focus specifically upon women’s bodies, extending this intensive exploration in the late 1970s into her research in Boston into primal theater—an approach based on improvisation and the search for raw, subconscious emotions—as well as a brief period of training as a midwife in New York. In both primal theater and maternity, Josefowitz saw an unidealized primal and primordial reality, and applied her ideas and research to her paintings and burgeoning choreographic practice.

Josefowitz continued to study dance at the renowned Dartington College of Arts in Devon, England from 1979 to 1983, where she met and learned from the masters of contemporary dance, Steve Paxton—co-founder with Trisha Brown of the Judson Dance Theater in New York and the inventor of the contact improvisation dance technique—and Mary Fulkerson, one of the founders of the anatomical release technique. At this time, Josefowitz also became involved in political activism, taking part in a number of demonstrations, marches and conferences supporting both the feminist movement and the gay and lesbian liberation movement, often creating posters to promote these events. She was notably part of the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camps, protesting the local storage of cruise missiles in Berkshire, England, and co-founded with Mara de Wit a women-only post-punk band called Lining Time, which became well-known among the activist circuits in South West England. Mirroring the increase in her engagement in political activism and feminism, Josefowitz’s art intensified its representation of female sensation and feeling.

While at Dartington, and during the years after she graduated, Josefowitz began more intensively seeking ways to dismantle the conventional hierarchy that separated performance and painting, and to reconcile these two mediums in a unified practice. This effort is typified by one of her first choreographic pieces, ‘Woodstock’ (1983), in which she playfully used dance and movement to animate her childhood memories of her grandparents’ house—and the accepting and loving community she encountered there—in Upstate New York.

Captivated by the immediacy of performance, Josefowitz extended this organic exploration of the human form into her drawings and paintings as well; she regularly sketched on tablecloths, napkins, receipts, invoices and postcards, while continuing to work in her notebooks, amassing a travelogue of the cities she visited. During this period in the late 1980s, she painted on kraft paper that she rolled onto the wall of her studio, which allowed her to modify the size of her paintings as she worked.

As the 1990s arrived, the intersection of Josefowitz’s performative and pictorial practices was achieving its greatest definition, while the figurative realm she had spent her career portraying in two dimensions gave way to increasing abstraction. A series of paintings based on her 1989 choreographic work ‘For Ever Young’ marked the beginning of a gradual disappearance of the body from Josefowitz’s oeuvre. This series, made in tribute following the tragic death of a friend and colleague, prominently features an empty chair, emblematic of the way in which the artist’s imagery would become more abstract, geometric and monochromatic in the ensuing decades.

As Josefowitz became increasingly engaged in the physicality of creation, pursuing her mission to collapse boundaries between performance and visual mark-making, she also began her painting sessions with a dance. Large-scale paintings from this period were no longer created on the wall of the artist’s studio, but on her floor, where Josefowitz moved, reached and swayed over the surface of her canvas in a highly calculated attempt to capture in oil paint the ephemeral action.

Following a diagnosis of breast cancer in 2007, Josefowitz’s work acquired an intensifying air of spirituality. She initiated a series of abstract kamasutra paintings in 2010, depicting couples set against airy and limitless monochrome backgrounds, which was followed by a series of musings and meditations on existence in the form of large-format paintings inspired by skies and landscapes, as well as her own emotional states, that she pursued until the day she died on 28 June 2014, in Geneva.

Image: Cathy Josefowitz, Untitled, 1974 c., Oil on cardboard, 97.7 x 68 cm / 38 1/2 x 26 3/4 in © Estate of Cathy Josefowitz

Inquire about works by Cathy Josefowitz

On view now through 22 July 2023 at Hauser & Wirth New York 69th Street.

Related Content

Current Exhibitions

1 / 10